Demographic Documents

Examining the consistency of de facto marital status between tax data and the 2016 Census

Skip to text

Text begins

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a number of Statistics Canada colleagues for their contribution to this study.

The early drafts of this document benefited from the input of Geneviève Ouellet, Claudine Provencher, Ana Fostik, Jean-François Simard, David Pelletier, Nora Galbraith and Anne Milan.

We would also like to thank Carol D’Aoust for all the layout work on the document and the Statistics Canada translation team for translating this study from French to English.

List of acronyms

CCB = Canada Child Benefit.

CRA = Canada Revenue Agency.

CSDD = Canadian Statistical Demographic Database.

GSS = General Social Survey.

IRCC = Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Summary

This article compares marital status as identified in the 2015 T1 tax data to what was provided in the 2016 Census using record linkage. One of the key findings is that, while the consistency is very high for persons who are either married or single, it is lower for persons who are divorced, separated or living common law.

Highlights

- Overall,

the consistency between marital status in the 2015 tax data and the 2016 Census

is relatively high.

- Almost 9 in 10 people have the same marital status in both sources.

- However,

the consistency varies, sometimes significantly, depending on the particular marital

status indicated in the census.

- Over 95% of the individuals who reported being married or single in the 2016 Census have the same marital status in tax data.

- Conversely, less than 75% of people who are divorced, separated or living common law have the same marital status in both sources.

- Marital

status consistency also varies based on province or territory of residence,

age, and sex.

- The territories, and to a lesser extent Quebec, have lower consistency rates than the rest of the country.

- Consistency is lower among young adults, especially those who are in common-law unions or separated.

- Although the consistency rates are generally similar for men and women, men who are widowed, divorced or separated have slightly lower rates than women.

1. Introduction

Tax data are increasingly used to study the Canadian population. These data have many advantages. In addition to reducing data production costs and the response burden for Canadians, tax data also reflect various demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the population. These data also make it possible to describe tax filers’ living arrangements. Various studies have been able to use this information to study diverse topics such as the economic integration of immigrants (Houle 2015) and the impact of separation on women’s income (Le Bourdais et al. 2016) as well as to compute estimates of the number of census families and households (Bérard-Chagnon 2014).

However, using tax data for statistical purposes also raises several questions. One of the main issues is that tax concepts differ from those in other demographic sources, such as the census. This situation mainly reflects the purpose for which the data are being used. Tax data are collected for very specific purposes, such as for establishing various tax credits and access to tax programs, whereas census data are collected for describing the Canadian population. If these conceptual differences are relatively significant, they can affect the scope and comparability of the results from studies conducted using tax data. Some studies have also highlighted the differences that are sometimes significant between tax and census concepts using record linkages, particularly for place of residence (Bérard-Chagnon 2017), divorce rates (Margolis and al. 2019) and immigrants’ year of admission (Statistics Canada 2017a).

In this context, the objective of this project is to measure the level of consistency of de facto marital status between tax data and the census data. This study is based on record linkage between the Canadian Statistical Demographic Database (CSDD) and the 2016 Census. The main advantage of using a linkage for this study is that it enables direct comparison of the marital status reported by tax filers with what is entered in the census instead of using only tabulations.Note

This study is limited to de facto marital status for two reasons. First, de facto marital status, rather than legal marital status, is more commonly utilized by census data users because it better reflects the conjugal reality of the population, especially in the context of a steady increase in common-law unions over time. Second, as described further in the following section, tax data do not measure legal marital status, in part because of a category specifically referring to common-law status.

The next section introduces the concepts pertaining to marital statusNote in the census and in tax data. The third section presents the record linkage used in this study. Finally, the fourth section presents the results of the study.

2. Comparison of the de facto marital status concepts in the census and tax data

The purpose of this section is to describe and compare the de facto marital status concepts in the census and tax data.

2.1. De facto marital status in the census

The census collection is conducted in May every five years among the population whose usual place of residence is in Canada.Note The de facto marital status variable is derived from two questions asked on the short-form census. The first question pertains to legal marital status and the second one to common-law status. The two questions asked in the 2016 Census are shown in Figure 1.

Description of Figure 1

This figure shows the 2 questions on legal marital status and common-law status in the 2016 Census.

By combining these two questions, de facto marital status can be derived with six categories: married, living common law, widowed, divorced, separated (but still legally married), and never legally married and not living common law (single). The definitions of each de facto marital status for the 2016 Census are shown in Table 1.

| Categories | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Married | This category includes persons who have legally married and are not separated, divorced or widowed. |

| Living common law | This category includes persons who are living with a person as a couple but who are not legally married to that person. |

| Never married (not living common law) (single) | This category includes persons who have never legally married and are not living with a person as a couple. |

| Separated (not living common law) | This category includes persons who are married but who are no longer living with their spouse (for reasons other than, for example, illness, work or school), have not obtained a divorce and are not living with a person as a couple. |

| Divorced (not living common law) | This category includes persons who have obtained a legal divorce, have not remarried and are not living with a person as a couple. |

| Widowed (not living common law) | This category includes persons who have lost their married spouse through death, have not remarried and are not living with a person as a couple. |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Statistical classifications, Classification of marital status. | |

In this study, several clarifications about the categories are relevant to note. The question about common-law status does not impose a minimum duration since the union began. Also, common-law status takes precedence over the other marital statuses. The “separated” category includes only people who are legally married but reporting themselves as separated. Like common-law status, this category does not impose a minimum duration on the separation. Moreover, separations from common-law unions are not recorded in the census. The “widowed” category implicitly includes only people who were legally married. Also, at the time of deriving this characteristic, children aged 14 or younger are automatically included in the “never married (single)” category.

2.2. De facto marital status in tax data

The definition of de facto marital status in tax data differs from the definition in the census. In tax data, marital status is the person’s civil status as of December 31 of the tax year. Therefore, the reference date is off by a few months from that of the census (month of May). Some people may have had a change in marital status between these two dates. Also, some categories are different from those in the census. The tax definitions for the categories “common-law partner” and “separated” and the box on the T1 form where the tax filer must enter their marital status are shown in the following two figures.

Description of Figure 2

This figure shows the Canada Revenue Agency’s definitions of marital status.

Description of Figure 3

This figure shows the marital status box on the Canada Revenue Agency’s T1 form for the 2015 tax year.

Unlike the census, tax data impose a duration for reporting as living common law or separated. In fact, to be considered as living common law with a common-law partner, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) sets a minimum duration of 12 continuous months or the presence of a dependent child. For the “separated” category, the CRA sets a minimum duration of 90 consecutive days.

In addition, the “widowed” and “separated” categories include people whose common-law partner has died or who have ended a common-law union, which is not the case for the census. Note that the “separated” category in the census adds the condition “but still legally married,” which is not the case in tax data. Because of these differences, special attention will be paid to these situations in this document.

Two last elements to consider for the purposes of comparing the concepts of marital status in census and tax data are the interpretation of the concepts by respondents and the impact of proxy answers. It is possible that some respondents misunderstand the concepts and provide an answer that does not correspond to what was intended to be measured. Since the census questionnaire is often filled by one member of the household, errors due to proxy answers are also possible. It is recognized that the quality of proxy responses is lower than that of responses obtained directly from respondents (Shields 2004). These response errors may undermine the comparisons made in this study.

3. Data used

The record linkage used in this study was done by matching the 2016 version of the CSDD with the 2016 Census.

The CSDD is a database built with administrative data from various sources including vital statistics, Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) tax data, and data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) on temporary residents and permanent residents.Note

The 2016 version of the CSDD was matched to the census using established linkage techniques (Brennan et al. 2017). The overall linkage rate is 95.5%. The matched file contains 32.3 million records.Note

Amongst the CSDD records that were linked to census data, some were excluded from the analyses because they did not appear in tax data. In total, the matched file used in this study has 25.2 million records for which the CSDD provides information on tax-related marital status.

The census data used are published data. Therefore, some values were imputed. The imputation rates are 4.3% for the marital status question and 5.1% for the common-law question (Statistics Canada 2017c). These rates reach 8% in some territories. These imputations can affect the consistency between the census data and tax data if the imputed value differs from the true value. In addition, other measurement errors, such as reporting errors, can also slightly undermine the comparison.

3.1. Measuring the consistency of de facto marital status

The consistency rates are obtained by calculating the proportion of the population with a given marital status according to the census who have the same marital status in the tax data. A rate of 100% means that the entire population of a given marital status according to the census has the same marital status in the tax data.

4. Results

This section starts with comparisons between the aggregate counts from the matched file for the two sources. The consistency rates are then presented by marital status and some demographic characteristics.

4.1. Aggregate evaluation

Before directly studying the consistency of de facto marital status between the two sources, this section presents some aggregate comparisons from the matched file. The matched file includes only the individuals in both sources who were matched. Therefore, it implicitly factors in the differences in the counts for both sources.

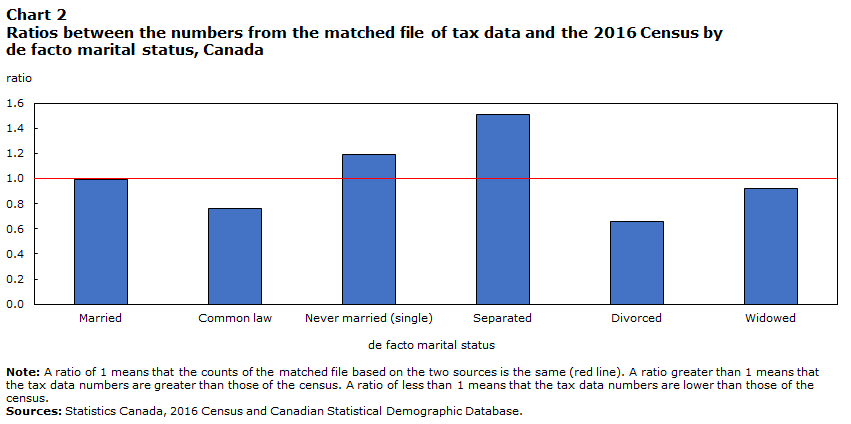

The following charts reflect, respectively, the distribution of marital status in the two sources examined and the ratios between the counts of these sources.

Data table for Chart 1

| De facto marital status | Tax data | Census |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Married | 48.8 | 49.2 |

| Common law | 9.7 | 12.8 |

| Never married (single) | 29.2 | 24.4 |

| Separated | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| Divorced | 4.1 | 6.3 |

| Widowed | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | ||

Data table for Chart 2

| De facto marital status | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Married | 0.99 |

| Common law | 0.76 |

| Never married (single) | 1.19 |

| Separated | 1.51 |

| Divorced | 0.66 |

| Widowed | 0.92 |

|

Note: A ratio of 1 means that the counts of the matched file based on the two sources is the same (red line). A ratio greater than 1 means that the tax data numbers are greater than those of the census. A ratio of less than 1 means that the tax data numbers are lower than those of the census. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

|

Although the distributions are quite similar overall, the matched data show larger differences in the counts of the two sources for some marital statuses.

The number of separated people in tax data far exceeds that in the census. For every 100 separated people in the census, the tax data count slightly over 150. Differences in the definitions of the “separated” category can explain this gap. The census defines this marital status as “separated but still legally married” whereas in the tax data, the definition of the “separated” marital status is broader and includes common-law separations in addition to marriage separations.

Tax data also have a higher count of single people than the census does (ratio of 1.19). Almost 30% of the population in the matched file are single according to tax data, compared with just under 25% according to the census. These results could be because of two factors. First, some government programs can provide a tax advantage to people reporting as single and living alone. Conversely, there can also be advantages to filing taxes jointly with a spouse or partner, such as income splitting, that could entice people to claim common-law status. Second, it is possible that the count of single people of tax data includes a relatively large number of people who have another marital status according to the census, essentially due to the conceptual differences noted above.

On the other hand, tax data show a lower count than the census for people living common-law (ratio of 0.76) and who are divorced (ratio of 0.66) people. Just under 10% of the population in the matched file are in a common-law union according to tax data, compared with almost 13% according to the census. These differences can be partly because the census, unlike tax data, does not impose a minimum duration on the definition of common-law partner. This conceptual difference could notably have a greater impact for new unions.

4.2. Consistency for Canada, the provinces and the territories

The following table shows the level of consistency of de facto marital status between tax data and the census for Canada.

| 2016 Census | Tax data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Common law | Never married (single) | Separated | Divorced | Widowed | Total | |

| percent | |||||||

| Married | 97.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 100.0 |

| Common law | 3.3 | 68.3 | 21.9 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 100.0 |

| Never married (single) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 96.1 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 100.0 |

| Separated | 11.8 | 0.8 | 14.5 | 70.2 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 100.0 |

| Divorced | 0.9 | 0.9 | 27.4 | 12.5 | 57.1 | 1.1 | 100.0 |

| Widowed | 2.6 | 0.3 | 8.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 86.6 | 100.0 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |||||||

Overall, marital status in tax data is the same as that in the census for 89.6% of the population in the matched file. However, the differences observed in the aggregate tabulations are reflected in the consistency rates. The consistency rates are highest for married people (97.2%) and single people (96.1%). This means that over 96% of married or single people according to the census have the same marital status in tax data. Conversely, the consistency rates are lowest among people who are divorced (57.1%), living common law (68.3%) or separated (70.2%). These disparities may arise from the differences in the concepts and reference dates between the two data sources.

A relatively large number of people who are living common law, separated or divorced according to the census reported being single in tax data. These proportions are 21.9%, 14.5% and 27.4%, respectively. In all three cases, being single is the most common tax marital status for people whose marital status is not the same as in the census.

For common-law status, the minimum duration in the definition of common-law partner in tax data (12 months) may explain why a lot of people living common law according to the census are single in tax data (21.9%). It could also be possible that many common-law couples could want to preserve some degree of tax independence even after 12 months of cohabitation and still declare being single for tax purposes.

The differences seen for people being separated according to the census and single according to tax data (14.5%) could arise from the minimum duration imposed by tax data for recent separations (less than 90 days). It may be that some separated people according to the census consider themselves single in tax data, especially if the separation occurred a number of years earlier. Also recall that the census imposes an additional condition for the “separated” category (excluding common-law separations).

Finally, the differences seen for people who reported being divorced in the census and single in tax data (27.4%) are more difficult to explain. In fact, to be considered divorced, one must, in principle, have been legally married previously, regardless of the data source used. It may be possible that some people who are separated with no intention of reconciliation could declare being divorced on census but not on tax data. These discrepancies could also potentially stem from the duration since the divorce. Some people could report being single in tax data when the divorce is less recent.

The following chart continues the analysis by showing the total consistency rate by province and territory.

Data table for Chart 3

| Region | Consistency rate |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 89.6 |

| N.L. | 90.6 |

| P.E.I. | 91.2 |

| N.S. | 89.5 |

| N.B. | 89.7 |

| Que. | 88.3 |

| Ont. | 90.2 |

| Man. | 90.7 |

| Sask. | 90.5 |

| Alta. | 89.7 |

| B.C. | 89.4 |

| Y.T. | 84.8 |

| N.W.T. | 86.6 |

| Nvt. | 84.6 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Overall consistency rates fluctuate moderately by province or territory. Marital status in tax data matches that of the census for more than 90% of the population living in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Conversely, the consistency rates are below 87% in the three territories. It is also somewhat lower in Quebec. The demographic reality of the territories and Quebec differs relative to that in the rest of the country, especially regarding the prevalence of common-law unions and the age structure of the population. These differences can explain the lower consistency rates seen for these jurisdictions.

The following charts continue this analysis by presenting the consistency rates by de facto marital status and by province or territory.

Data table for Chart 4a

| Region | Married population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 97.2 |

| N.L. | 98.1 |

| P.E.I. | 98.5 |

| N.S. | 98.0 |

| N.B. | 98.0 |

| Que. | 95.6 |

| Ont. | 97.4 |

| Man. | 97.9 |

| Sask. | 98.1 |

| Alta. | 97.5 |

| B.C. | 97.5 |

| Y.T. | 96.5 |

| N.W.T. | 95.9 |

| Nvt. | 92.2 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Data table for Chart 4b

| Region | Common law population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 68.3 |

| N.L. | 60.2 |

| P.E.I. | 60.4 |

| N.S. | 58.2 |

| N.B. | 66.2 |

| Que. | 82.7 |

| Ont. | 55.5 |

| Man. | 60.5 |

| Sask. | 58.3 |

| Alta. | 54.9 |

| B.C. | 57.4 |

| Y.T. | 68.6 |

| N.W.T. | 71.2 |

| Nvt. | 75.1 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Data table for Chart 4c

| Region | Never married (single) population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 96.1 |

| N.L. | 97.4 |

| P.E.I. | 97.4 |

| N.S. | 97.4 |

| N.B. | 96.0 |

| Que. | 92.6 |

| Ont. | 97.6 |

| Man. | 97.2 |

| Sask. | 97.0 |

| Alta. | 97.0 |

| B.C. | 97.4 |

| Y.T. | 95.0 |

| N.W.T. | 94.0 |

| Nvt. | 90.2 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Data table for Chart 4d

| Region | Separated population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 70.2 |

| N.L. | 70.4 |

| P.E.I. | 72.7 |

| N.S. | 72.2 |

| N.B. | 73.0 |

| Que. | 70.1 |

| Ont. | 71.2 |

| Man. | 70.9 |

| Sask. | 67.5 |

| Alta. | 67.6 |

| B.C. | 68.2 |

| Y.T. | 52.7 |

| N.W.T. | 59.0 |

| Nvt. | 52.1 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Data table for Chart 4e

| Region | Divorced population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 57.1 |

| N.L. | 53.6 |

| P.E.I. | 57.4 |

| N.S. | 57.0 |

| N.B. | 55.0 |

| Que. | 58.3 |

| Ont. | 56.5 |

| Man. | 55.7 |

| Sask. | 57.0 |

| Alta. | 58.7 |

| B.C. | 56.2 |

| Y.T. | 34.9 |

| N.W.T. | 43.6 |

| Nvt. | 45.0 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

Data table for Chart 4f

| Region | Widowed population |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| Canada | 86.6 |

| N.L. | 88.7 |

| P.E.I. | 90.1 |

| N.S. | 88.7 |

| N.B. | 88.0 |

| Que. | 85.4 |

| Ont. | 87.1 |

| Man. | 86.4 |

| Sask. | 88.7 |

| Alta. | 86.4 |

| B.C. | 85.9 |

| Y.T. | 75.9 |

| N.W.T. | 73.5 |

| Nvt. | 75.7 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | |

The “married” and “single” categories are very consistent from one jurisdiction to another. However, provincial and territorial variations are more significant for the common-law, divorced and separated populations. They are as well for widowed people, but to a lesser degree.

More than 80% of the population residing in Quebec who live common law according to the census are also living common law according to tax data. This proportion exceeds the national average by almost 15 percentage points. In Quebec, common-law unions are a much more common and stable type of union than in the rest of the country (Statistics Canada 2017b) and are gradually replacing marriage (Le Bourdais and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2004). However, even in Quebec, common-law unions are more unstable than those that turn into marriages or direct marriages, even after the birth of a child (Le Bourdais et al. 2014). Therefore, the higher stability and increased social recognition of common-law unions could explain, on the one hand, the higher consistency rates of common-law unions in Quebec and, on the other, the fact that these rates are still lower than those of married people in that province.

The population living in the territories stands out from that of the rest of the country through lower consistency rates for divorced and separated people and, to a lesser extent, for widowed people. The population of the territories also shows lower consistency rates for the other marital statuses, except for common-law unions, where the situation is reversed. The territories are less populated than the provinces and have a large Indigenous population. The concept of family among Indigenous peoples tends to differ from that of the rest of the country (Tam and Findlay 2017), which may be reflected in marital status consistency.

4.3. Consistency by sex and age

The following charts show the consistency rate of de facto marital status by sex and age, respectively.

Data table for Chart 5

| De facto marital status | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Married | 97.2 | 97.3 |

| Common law | 68.4 | 68.2 |

| Never married (single) | 96.4 | 95.7 |

| Separated | 66.5 | 72.9 |

| Divorced | 50.0 | 61.6 |

| Widowed | 81.0 | 88.2 |

| Total | 89.8 | 89.3 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. | ||

The total consistency rates are similar for men (89.8%) and women (89.3%).

However, men show lower consistency rates than women in the “separated,” “divorced” and “widowed” categories. The differences are particularly pronounced in the “divorced” category. For this marital status, the consistency rate for women (61.6%) is more than 10 percentage points higher than it is for men (50.0%). Women are proportionately more likely to be divorced, separated or widowed than their male counterparts, regardless of age, which can be explained by the fact that men are more likely to repartner than women (Ménard and Le Bourdais 2012). These more frequent changes in marital status for men could partly explain the differences observed for these three marital statuses.

Data table for Chart 6

| Age group | Married | Common law | Never married (single) | Separated | Divorced | Widowed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||||||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 99.2 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 99.2 |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 99.8 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 98.6 |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 99.2 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 91.8 |

| 25 to 29 years | 91.3 | 55.7 | 97.4 | 58.7 | 35.7 | 31.5 | 85.3 |

| 30 to 34 years | 94.6 | 68.6 | 94.5 | 67.4 | 42.1 | 47.9 | 87.3 |

| 35 to 39 years | 96.2 | 75.6 | 91.5 | 70.8 | 46.6 | 62.9 | 88.9 |

| 40 to 44 years | 96.9 | 74.5 | 90.1 | 72.3 | 50.2 | 69.9 | 88.8 |

| 45 to 49 years | 97.2 | 72.1 | 90.5 | 71.7 | 51.9 | 72.2 | 88.1 |

| 50 to 54 years | 97.5 | 72.0 | 91.7 | 71.2 | 53.4 | 74.7 | 87.9 |

| 55 to 59 years | 97.9 | 74.2 | 93.1 | 70.7 | 56.1 | 79.1 | 88.9 |

| 60 to 64 years | 98.3 | 76.4 | 94.4 | 70.7 | 59.8 | 83.2 | 90.2 |

| 65 to 69 years | 98.7 | 78.0 | 94.9 | 72.2 | 63.6 | 85.6 | 91.3 |

| 70 to 74 years | 98.9 | 76.7 | 94.5 | 70.7 | 66.0 | 87.2 | 92.0 |

| 75 to 79 years | 98.9 | 72.0 | 94.0 | 66.8 | 66.4 | 88.7 | 92.3 |

| 80 to 84 years | 98.7 | 67.4 | 93.2 | 63.0 | 66.5 | 90.1 | 92.4 |

| 85 years or over |

97.7 | 60.0 | 92.8 | 52.8 | 63.3 | 91.3 | 91.7 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category and the total. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

|||||||

Marital status consistency varies, sometimes significantly, based on age. The total consistency rates by age group vary from nearly 100% for young people aged 0 to 19 to 85.3% for the population aged 25 to 29. The rates then climb back up to 90% and stay there among people aged 60 or older.

The “married” and “single” categories show the highest consistency rates for each age group. The rates for these two marital statuses are over 90% for all age groups considered.

Common law is the second most prevalent marital status among the population aged 25 to 29. However, the consistency rate for this marital status is 55.7% for this age group. In addition, over 40% of people aged 25 to 29 who are in a common-law union according to the census are single in the tax data. These results could be because it is during this period that young adults start their conjugal lives, many of them in common-law unions. However, these initial common-law unions are often short (Ménard 2011), which can explain the differences between the census data and tax data. Recall that tax data impose a 12-month union duration or the presence of a dependent childNote for a common-law union to be reported, which is not the case for the census.

The consistency rates for common-law unions increase with age as the conjugal history unfolds and stabilizes. These rates drop below 70% again for those aged 80 or older. However, common-law unions are much less common at these ages.

Other significant differences by age group are seen in the “widowed”, “divorced” and “separated” categories. The consistency rates for the “separated” category by age follow a similar pattern as that for common-law status. In addition, the consistency rates for the “widowed” and “divorced” categories change in a similar way based on age, although that increase is more pronounced for the “widowed” category. Note that, although the consistency rates of divorced and widowed people are lower among young adults, very few people of these ages live in these situations. Finally, the consistency rate for the “widowed” category is over 90% for the population aged 80 and older, where it is a very prevalent marital status.

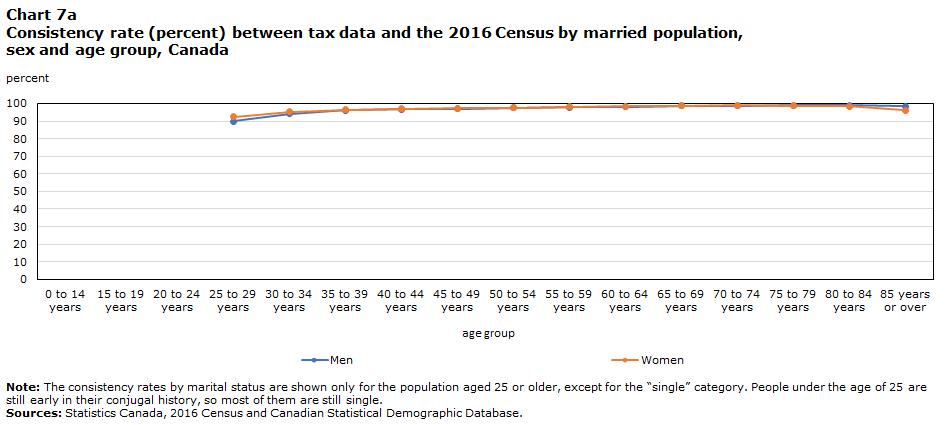

The following charts show the consistency rates by age group and sex.

Data table for Chart 7a

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 29 years | 89.8 | 92.3 |

| 30 to 34 years | 94.0 | 95.2 |

| 35 to 39 years | 96.0 | 96.5 |

| 40 to 44 years | 96.7 | 97.0 |

| 45 to 49 years | 97.1 | 97.2 |

| 50 to 54 years | 97.4 | 97.5 |

| 55 to 59 years | 97.8 | 98.0 |

| 60 to 64 years | 98.2 | 98.5 |

| 65 to 69 years | 98.6 | 98.8 |

| 70 to 74 years | 98.8 | 98.9 |

| 75 to 79 years | 98.9 | 98.8 |

| 80 to 84 years | 98.9 | 98.3 |

| 85 years or over | 98.5 | 96.2 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

Data table for Chart 7b

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 29 years | 53.3 | 57.6 |

| 30 to 34 years | 66.8 | 70.5 |

| 35 to 39 years | 74.8 | 76.4 |

| 40 to 44 years | 74.7 | 74.3 |

| 45 to 49 years | 72.8 | 71.5 |

| 50 to 54 years | 72.0 | 72.1 |

| 55 to 59 years | 73.5 | 74.9 |

| 60 to 64 years | 75.6 | 77.4 |

| 65 to 69 years | 77.6 | 78.6 |

| 70 to 74 years | 77.3 | 75.7 |

| 75 to 79 years | 73.7 | 68.9 |

| 80 to 84 years | 69.7 | 62.4 |

| 85 years or over | 62.9 | 52.5 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

Data table for Chart 7c

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | 99.5 | 98.7 |

| 15 to 19 years | 99.9 | 99.7 |

| 20 to 24 years | 93.9 | 99.0 |

| 25 to 29 years | 97.9 | 96.7 |

| 30 to 34 years | 95.2 | 93.6 |

| 35 to 39 years | 92.3 | 90.5 |

| 40 to 44 years | 90.6 | 89.5 |

| 45 to 49 years | 90.8 | 90.1 |

| 50 to 54 years | 92.0 | 91.4 |

| 55 to 59 years | 93.1 | 93.2 |

| 60 to 64 years | 94.2 | 94.7 |

| 65 to 69 years | 94.7 | 95.1 |

| 70 to 74 years | 94.5 | 94.5 |

| 75 to 79 years | 94.0 | 94.0 |

| 80 to 84 years | 92.8 | 93.5 |

| 85 years or over | 91.5 | 93.4 |

|

Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

Data table for Chart 7d

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 29 years | 48.9 | 63.6 |

| 30 to 34 years | 59.7 | 71.6 |

| 35 to 39 years | 64.8 | 74.3 |

| 40 to 44 years | 67.6 | 75.1 |

| 45 to 49 years | 68.1 | 74.1 |

| 50 to 54 years | 68.3 | 73.4 |

| 55 to 59 years | 67.2 | 73.6 |

| 60 to 64 years | 67.1 | 73.8 |

| 65 to 69 years | 69.7 | 74.4 |

| 70 to 74 years | 69.4 | 71.9 |

| 75 to 79 years | 67.2 | 66.4 |

| 80 to 84 years | 63.5 | 62.4 |

| 85 years or over | 54.2 | 50.9 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

Data table for Chart 7e

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 29 years | 29.6 | 38.9 |

| 30 to 34 years | 36.2 | 45.5 |

| 35 to 39 years | 39.5 | 50.6 |

| 40 to 44 years | 43.1 | 54.2 |

| 45 to 49 years | 45.1 | 56.2 |

| 50 to 54 years | 46.8 | 57.9 |

| 55 to 59 years | 49.4 | 60.8 |

| 60 to 64 years | 52.1 | 65.0 |

| 65 to 69 years | 55.7 | 68.6 |

| 70 to 74 years | 58.4 | 70.7 |

| 75 to 79 years | 59.6 | 70.5 |

| 80 to 84 years | 60.5 | 69.8 |

| 85 years or over | 58.3 | 65.4 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

Data table for Chart 7f

| Age group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 14 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 15 to 19 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 20 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 29 years | 10.1 | 50.1 |

| 30 to 34 years | 24.8 | 60.9 |

| 35 to 39 years | 43.3 | 70.3 |

| 40 to 44 years | 55.7 | 74.4 |

| 45 to 49 years | 62.8 | 75.4 |

| 50 to 54 years | 66.6 | 77.4 |

| 55 to 59 years | 72.5 | 81.1 |

| 60 to 64 years | 77.0 | 84.9 |

| 65 to 69 years | 80.5 | 87.0 |

| 70 to 74 years | 82.5 | 88.4 |

| 75 to 79 years | 84.7 | 89.7 |

| 80 to 84 years | 86.5 | 91.1 |

| 85 years or over | 88.1 | 92.1 |

|

... not applicable Note: The consistency rates by marital status are shown only for the population aged 25 or older, except for the “single” category. People under the age of 25 are still early in their conjugal history, so most of them are still single. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||

The level of consistency of the “married,” “common law” and “single” categories is very similar for men and women.

However, examining the consistency rates by age group and sex primarily highlights the gap between men and women for the “divorced” and “separated” categories.Note In the former case, the gap continues through the ages, with the consistency being systematically higher among women. In the second case, the gap is wider among young adults and tends to narrow after that. The differential conjugal behaviours between men and women after a union ends, as previously mentioned, may partly explain these differences.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the consistency of de facto marital status between tax data and the 2016 Census data. It fits into a context where tax data are increasingly used to describe households and families in Canada.

The concepts related to marital status in tax data differ from those of the census. The census data provide information on legal marital status and common-law status. Responses to these two questions are combined to derive de facto marital status. The information from tax data is obtained from tax returns. The reference date for tax data is December 31 of the tax year. This differs from the census, which takes place in May. In addition, tax data impose a minimum duration for common-law union formation or since a separation, which is not the case for the census. Other differences are also noteworthy for other categories, such as separation and widowhood, which, in tax data, can result from the end of a common-law union and not just the end of a marriage.

The overall consistency between de facto marital status in tax data and in the census is nearly 90%. However, this rate masks significant differences by marital status. The consistency is significantly lower for divorced people (57.1%), people living common law (68.3%) and separated people (70.2%). The tax data also count significantly more separated people and fewer people who are divorced or living common law in the matched file used for this study. The conceptual differences described above and the mismatch in the reference date could explain these differences.

The level of consistency of these three marital statuses is particularly low among young adults. These ages are associated with the formation and dissolution of unions. This suggests that the conceptual differences between tax data and the census data, especially regarding the imposition of a minimum duration for common-law unions and separation, may have a greater impact at these ages.

The consistency rates tend to be lower in the territories and, to a lesser extent, in Quebec. These jurisdictions have a higher level of prevalence of common-law unions, which tend to have a lower level of consistency than most other marital statuses.

The sex-based analysis highlighted that men have generally lower consistency rates for the “separated” and “divorced” categories. These results may reflect differential behaviours between men and women relative to the dissolution and formation of unions.

Overall, two main conclusions emerge from this study.

First, the differences between tax data and census data are greater for the less stable marital statuses and for young adults. These results suggest that the differences between the two sources are greater for transition periods, particularly for the beginning of conjugal life, which is a common-law union in the majority of cases (Wright 2016). Therefore, the imposition of a one-year minimum duration for common-law unions in tax data can significantly reduce the number of young adults living common law in these data, especially among those who have just started their conjugal lives and have not yet celebrated their first anniversary of life together.

Second, the results by province and territory indicate that the differences between the two sources may be greater for some groups that are more numerous in certain provinces and territories such as Indigenous peoples in the territories and Francophones in Quebec. Also, because of the highly cultural nature of the concept of family, it is possible for the levels of consistency to also vary for recent immigrants. Although the purpose of this study was not to examine consistency for specific subgroups of the population, it is an interesting avenue for future projects, especially in the context of the growing popularity of common-law unions, the steady increase in immigration, and the robust growth of the Indigenous population.

The results of this study have a number of implications.

First, family transitions are often associated with other significant transitions in individuals’ lives. Therefore, the results of this study indicate that tax data capture the evolution of some family trajectories differently than the census data. More in-depth analysis, combining the census data, tax data and the data from the General Social Survey (GSS) on families — which collects the start and end dates of every union, the type of union and the type of union dissolution (separation, divorce or death of the spouse or partner) — could contribute to a better understanding of the differences observed and provide some additional reflections.

Second, in a context where administrative data are increasingly used to describe the Canadian population, the results of this study reinforce the importance of examining the concepts used in administrative data. These differences must be considered because they can significantly impact the interpretation of the data.

In conclusion, this study revealed several significant differences between marital status reported in the tax data and in the census. It also reiterated the importance of reflecting on the concepts used in the tax data and other administrative sources, in a context where these data are increasingly used to report on the demographic dynamics of the Canadian population. In addition, census concepts also continue to evolve over time to better reflect the conjugal and family lives of Canadians.

References

BÉRARD-CHAGNON, Julien. 2014. “Using Tax Data to Estimate the Number of Families and Households in Canada”. Emerging Techniques in Applied Demography. Applied Demography Serie 4. Nazrul Hoque and Lloyd B. Potter editors. Springer. Pages 137 to 153.

BÉRARD-CHAGNON, Julien. 2017. “Comparison of Place of Residence between the T1 Family File and the Census: Evaluation using record linkage”. Demographic Documents. September 26, 2017. Statistics Canada catalogue number 91F0015M. 44 pages.

BÉRARD-CHAGNON, Julien and Marie-Noëlle PARENT. 2021. “Coverage of the 2016 Census: Level and trends”. Demographic Documents. January 26, 2021. Statistics Canada catalogue number 91F0015M. 22 pages.

BRENNAN, Jim, Alex DIAZ-PAPKOVICH and Xuan QI. 2017. CSDD2016 to Census2016 Linkage. Internal document. Social Survey Methods Division. 24 pages.

HOULE, René. 2015. “Economic Integration of French-speaking Immigrants Outside Quebec: A Longitudinal Approach”. Research Report. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Reference number R7-2014. 67 pages.

LE BOURDAIS, Céline and Évelyne LAPIERRE-ADAMCYK. 2004. “Changes in Conjugal Life in Canada: Is Cohabitation Progressively Replacing Marriage?”. Journal of Marriage and Family. Volume 66, number 4 (November 2004). Pages 929 to 942.

LE BOURDAIS, Céline, Évelyne LAPIERRE-ADAMCYK and Alain ROY. 2014. “The instability of common-law relationships: A comparative analysis of demographic factors”. Recherches sociographiques. Volume 55, number 1. Pages 53 to 78.

LE BOURDAIS, Céline, Sung-Hee JEON, Shelley CLARK and Évelyne LAPIERRE-ADAMCYK. 2016. “Impact of conjugal separation on women’s income in Canada: Does the type of union matter?”. Demographic Research. Volume 35, article 50. Pages 1,489 to 1,522.

MARGOLIS, Rachel, Youjin CHOI, Feng HOU and Michael HAAN. 2019. “Capturing trends in Canadian divorce in an era without vital statistics”. Demographic Research. December 20, 2019. Volume 41, article 52. Pages 1,453 to 1,478.

MÉNARD, France-Pascale. 2011. “What Makes It Fall Apart? The Determinants of the Dissolution of Marriages and Common-Law Unions in Canada”. McGill Sociological Review. Volume 2. April 2011. Pages 59 to 76.

MÉNARD, France-Pascale and Céline LE BOURDAIS. 2012. “Diversification des trajectoires familiales des Canadiens âgés de demain et conséquences prévisibles sur le réseau de soutien”. Cahiers québécois de démographie. Volume 41, number 1. Pages 131 to 161.

SHIELDS, Margot. 2004. “Proxy reporting in the National Population Health Survey”. Health Reports. Volume 12, number 1. Statistics Canada Catalogue number 82-003. 19 pages.

STATISTICS CANADA. 2017a. “2016 Census of Population of Canada: Integration of immigration administrative data”. UNECE Work Session on Migration Statistics. Geneva, Switzerland. October 30-31, 2017. 13 pages.

STATISTICS CANADA. 2017b. “Researching a new approach to census-taking”. Census Program Transformation Project Updates. August 11, 2017. Catalogue number 98-506-X. 5 pages.

STATISTICS CANADA. 2017c. “Families Reference Guide”. Census of Population, 2016. August 2, 2017. Catalogue number 98-500-X2016002. 9 pages.

STATISTICS CANADA. 2017d. “Families, households and marital status: Key results from the 2016 Census”. The Daily. August 2, 2017. 11 pages.

TAM, Benita Y. and Leanne C. FINDLAY. 2017. “Indigenous families: who do you call family?”. Journal of Family Studies. Volume 23, number 3. Pages 243 to 259.

WRIGHT, Laura. 2016. “Type and timing of first union formation in Québec and the rest of Canada: Continuity and change across the 1930–79 birth cohorts”. Canadian Studies in Population. Volume 43, number 3–4. Pages 234 to 248.

Appendix

The following table shows the de facto marital status of the population excluded from this study. These exclusions can occur if an individual is missing from one of the two files, was not matched, or because no marital status information was available in the tax data.

| Category | De facto marital status from tax data for individuals missing from census or not linked | De facto marital status from census for individuals missing from the CSDD, not linked or without marital status information | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | |

| percent | percent | |||

| Married | 910,421 | 18.3 | 17,221 | 0.3 |

| Common law | 163,713 | 3.3 | 11,275 | 0.2 |

| Single | 1,721,967 | 34.6 | 6,240,700 | 99.5 |

| Separated | 229,749 | 4.6 | 1,066 | 0.0 |

| Divorced | 186,284 | 3.7 | 1,128 | 0.0 |

| Widowed | 322,837 | 6.5 | 1,171 | 0.0 |

| Married or living common-law | 1,069 | 0.0 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Non declared | 12,116 | 0.2 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Missing value | 75,637 | 1.5 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| No value | 1,347,582 | 27.1 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Total | 4,971,375 | 100.0 | 6,272,561 | 100.0 |

|

... not applicable Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census and Canadian Statistical Demographic Database. |

||||

More than one in three people who were missing from the census or not matched are single according to tax data. This result reflects the fact that census coverage tends to be lower for single people (Bérard-Chagnon and Parent 2021).

Almost 30% of the population missing from the census or unable to be matched have a missing or absent value for marital status in the tax data. The majority of these are children who have never filed a tax return and are added to the CSDD using other data, such as the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). This is not a major limitation of the analysis because children under the age of 15 are automatically categorized as single in the census.

Just under 20% of the people missing from the census or not matched are married according to tax data. Although this proportion is relatively large, it is still well below the demographic weight of married people in the Canadian population. According to the 2016 Census, nearly 40% of the Canadian population aged 15 years and older was married.

On the other hand, the vast majority of the people who have no marital status in the tax data are single. These cases are almost all children, who are automatically categorized as single in the census. In fact, over 97% of children aged 0 to 14 do not have marital status information in tax data.

- Date modified: