Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2019

Analysis: Total Population

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Skip to text

Text begins

The estimates in this publication are based on 2016 Census counts, adjusted for census net undercoverage and incompletely enumerated Indian reserves, plus the estimated population growth for the period from May 10, 2016, to the date of the estimate.

The analysis in this publication is based on preliminary data. These data will be revised over the coming years, and some trends described in this publication could change as a result of these revisions. Therefore, this publication should be interpreted with caution.

This section presents the population estimates for Canada, the provinces and territories on July 1, 2019, along with a concise analysis of the various components of population growth between July 1, 2018, and July 1, 2019.

Canada’s population reaches 37.6 million

On July 1, 2019, Canada’s population was estimated at 37,589,262, up 531,497 from July 1, 2018. The increase is above the 500,000-mark for a second consecutive year and represents the strongest growth, in absolute numbers, since Confederation,Note surpassing the previous maximum of 529,200 seen in 1956/1957, in the peak baby-boom period and at a time when many Hungarian refugees arrived in the country.Note

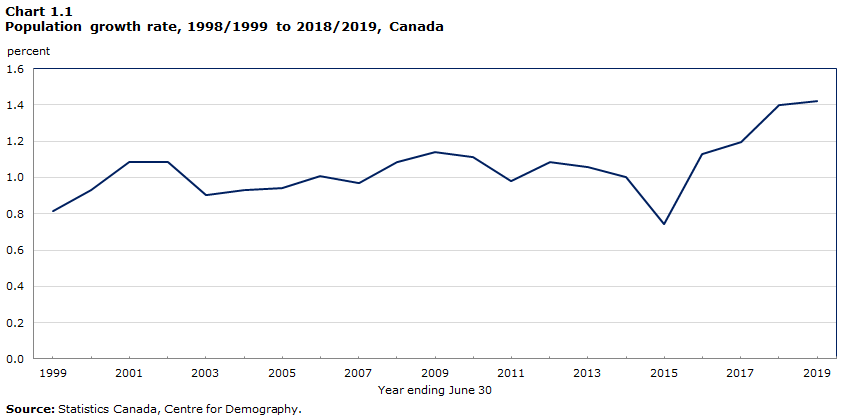

Data table for Chart 1.1

| Year ending June 30 | percent |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 0.81 |

| 2000 | 0.93 |

| 2001 | 1.09 |

| 2002 | 1.09 |

| 2003 | 0.90 |

| 2004 | 0.93 |

| 2005 | 0.94 |

| 2006 | 1.01 |

| 2007 | 0.97 |

| 2008 | 1.08 |

| 2009 | 1.14 |

| 2010 | 1.11 |

| 2011 | 0.98 |

| 2012 | 1.09 |

| 2013 | 1.06 |

| 2014 | 1.01 |

| 2015 | 0.75 |

| 2016 | 1.13 |

| 2017 | 1.19 |

| 2018 | 1.40 |

| 2019 | 1.42 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | |

Canada posts the strongest population growth among the G7 countries

Canada’s population maintained its growth rate at 1.4%Note in 2018/2019, the highest rate since 1989/1990 (+1.5%).

During the past year, population growth in Canada remained the highest among G7 countries. In fact, its population growth rate was more than twice that of the United States (+0.6%), tied for second with the United Kingdom (+0.6%). It was also much higher than that of all the other G7 countries that posted an increase: Germany (+0.3%) and France (+0.2%). Finally, it contrasts with the population decline observed in Italy and Japan (-0.2% each).

However, Canada’s population growth was not the highest among the industrialized countries, coming in lower than the increases posted in Australia and New Zealand (+1.6% each).Note

Data table for Chart 1.2

| Country | rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Canada | 1.4 |

| United States | 0.6 |

| United Kingdom | 0.6 |

| Germany | 0.3 |

| France | 0.2 |

| Italy | -0.2 |

| Japan | -0.2 |

|

|

International migration is the main source of population growth

Population growth at the national level is based on two factors: natural increaseNote and international migratory increase,Note while provincial and territorial population estimates also factor in interprovincial migration.

Between July 1, 2018, and July 1, 2019, international migratory increase was 436,689, the highest level ever estimated. This figure exceeds the last peak of 418,273 recorded last year by more than 18,000.

Since 1993/1994, international migration has consistently been the main driver of population growth in Canada. In the past year, over 80% of population growth stemmed from international migratory growth (82.2%), a level unmatched in history. By comparison, international migratory increase accounted for 40.4% of the population growth in 1990/1991.

In the past year, natural increase totalled 94,808, the lowest level recorded in Canada,Note led by the growing number of deaths due to population aging. Natural increase in 2018/2019 stemmed from the gap between the estimated 382,533 births and the estimated 287,725 deaths.

Data table for Chart 1.3

| Year ending June 30 | Natural increase | Net international migration | Population growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | |||

| 1999 | 120,663 | 135,427 | 246,113 |

| 2000 | 119,683 | 174,769 | 284,444 |

| 2001 | 107,993 | 236,700 | 335,172 |

| 2002 | 107,661 | 237,935 | 339,177 |

| 2003 | 106,618 | 183,749 | 283,949 |

| 2004 | 108,933 | 194,128 | 296,627 |

| 2005 | 109,364 | 200,154 | 303,098 |

| 2006 | 120,593 | 216,093 | 327,421 |

| 2007 | 127,091 | 219,749 | 317,851 |

| 2008 | 137,170 | 249,993 | 358,093 |

| 2009 | 141,582 | 269,184 | 381,777 |

| 2010 | 142,235 | 262,750 | 375,994 |

| 2011 | 131,456 | 230,981 | 334,439 |

| 2012 | 136,430 | 260,564 | 374,894 |

| 2013 | 129,951 | 260,820 | 368,732 |

| 2014 | 129,229 | 247,290 | 354,481 |

| 2015 | 117,154 | 170,354 | 265,473 |

| 2016 | 121,492 | 304,047 | 406,579 |

| 2017 | 105,218 | 328,616 | 433,834 |

| 2018 | 96,171 | 418,273 | 514,444 |

| 2019 | 94,808 | 436,689 | 531,497 |

|

Note: Until 2016 inclusively, population growth is not equal to the sum of natural increase and international migratory increase because residual deviation must also be considered in the calculation. Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. |

|||

International migratory growth peaks in several provinces

Since the beginning of the period covered by the current demographic accounting system (July 1971), record high international migratory increases have been observed in practically all provinces, particularly in Prince Edward Island (+3,235), Nova Scotia (+10,073), New Brunswick (+6,557), Quebec (+83,482), Ontario (+199,638), Saskatchewan (+15,387) and British Columbia (+58,993). International migration was also high in the other provinces.

Last year’s unprecedented level of international migration was driven by strong immigration levels and the arrival of many non-permanent residents.Note First, Canada granted immigrant status to 313,580 people between July 1, 2018, and July 1, 2019, one of the highest levels in Canadian history. These record levels were mostly seen between 1911 and 1913, a period marked by the mass arrival of non-British immigrants from Europe who settled in the Prairies. The recent peak recorded in 2015/2016 (323,192 immigrants) is partly on account of many Syrian refugees received as new immigrants.

Second, the number of non-permanent residents increased by 171,536 during the last year. This increase is the highest observed over the study period, i.e., from 1971 to 2019, topping the peak of 162,699 recorded last year, and the 140,748 non-permanent residents recorded in 1988/1989.Note Although also fuelled by a rapid increase in asylum claimants, the increase in the number of non-permanent residents to the country in 2018/2019 was mostly driven by an increase in the number of work and study permit holders.Note

Various factors can affect international migratory growth variations and trends. For example, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is regularly called on to revise the brackets for immigration levels, in keeping with the framework set out in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA).Note The recent rise in the number of immigrants is also consistent with the levels established by IRCC.Note In addition, the number of non-permanent residents can fluctuate depending on the economic and political climate in Canada and elsewhere in the world. There are three main categories of non-permanent residents: work permit holders, study permit holders, and asylum claimants. The number of work and study permit holders can rise or fall depending on the economic context of the country of origin and the host country, as well as the directions of certain programs in Canada and in the provinces and territories. The number of asylum claimants can vary, particularly depending on the political context in their country of origin, but also on certain decisions made in Canada. Lastly, emigration trends are more closely linked to both the internal and external economic situation.

More than four in five Canadians live in four provinces

On July 1, 2019, more than 32.5 million Canadians (86.4%) resided in one of the four most populous provinces: Ontario (38.8%), Quebec (22.6%), British Columbia (13.5%) and Alberta (11.6%). Ontario remained the country’s most populated province, with 14,566,547 people, followed by Quebec (8,484,965), British Columbia (5,071,336) and Alberta (4,371,316).

Data table for Chart 1.4

| Provinces and territories | Population on July 1, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Ont. | 14,566,547 |

| Que. | 8,484,965 |

| B.C. | 5,071,336 |

| Alta. | 4,371,316 |

| Man. | 1,369,465 |

| Sask. | 1,174,462 |

| N.S. | 971,395 |

| N.B. | 776,827 |

| N.L. | 521,542 |

| P.E.I. | 156,947 |

| N.W.T. | 44,826 |

| Y.T. | 40,854 |

| Nvt. | 38,780 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | |

Population growth accelerates in Eastern and Central Canada

Except in Newfoundland and Labrador, the other Atlantic provinces experienced population growth in 2018/2019, which was among the highest since 1971,Note at 2.2% in Prince Edward Island, 1.2% in Nova Scotia and 0.8% in New Brunswick. The highest population growth in the country was seen in Prince Edward Island, mainly due to a strong international migratory growth. Newfoundland and Labrador (-0.8%) was the only province that recorded a population decrease, for the third consecutive year.

In Quebec, the last time a population growth rate higher than that recorded last year (+1.2%) was observed was in 1988/1989 (+1.3%). Thus, international migration was higher in 2018/2019 than it was at that time.

Ontario maintained a population growth rate of 1.7% in 2018/2019, the second highest among the provinces, well over the provincial average of 1.0% between 2001/2002 and 2016/2017. In addition, for the first time since the late 1980s, Ontario’s population growth rate surpassed Alberta’s for the third consecutive year. A stronger international migratory growth in Ontario than in Alberta was behind this gap.

In Alberta, population growth increased in 2018/2019 for the second consecutive year, after four years of downturn. In fact, the province recorded a population growth of 1.6% in 2018/2019, compared with 1.3% the previous year.

In Saskatchewan (+1.0%), population growth in 2018/2019 was among the lowest in the past 13 years, where the province recorded a growth, mainly due to higher interprovincial migration losses. Population growth continued to slow down in Manitoba (+1.2%), and higher international migration further reduced interprovincial migratory losses compared with Saskatchewan.

Moreover, British Columbia’s population growth (+1.4%) in 2018/2019 was among the lowest in the last five years, mainly due to lower interprovincial migratory gains.

Lastly, in the territories, Nunavut (+1.7%) posted the second-highest population growth in Canada, tied with Ontario, while Yukon was at 0.6%. High fertility explained the marked growth in Nunavut. In contrast, the Northwest Territories population declined by 0.3% in 2018/2019, mainly due to interprovincial migratory losses.

Data table for Chart 1.5

| Provinces and territories | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2017/2018 (Canada) | 2018/2019 (Canada) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| N.L. | -0.5 | -0.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| P.E.I. | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| N.S. | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| N.B. | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Que. | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Ont. | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Man. | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Sask. | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Alta. | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| B.C. | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Y.T. | 2.3 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| N.W.T. | 0.1 | -0.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Nvt. | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | ||||

International migratory growth is the main driver of population growth in the provinces

Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia were the only provinces where each of the three population growth factors contributed positively to population growth. In Ontario and British Columbia, population growth stemmed mainly from international migratory growth. In Alberta, natural increase and international migratory growth both contributed to the province’s population growth.

Quebec, Manitoba and Saskatchewan owed a large share of their population growth to international migration and, to a lesser extent, natural increase. However, these provinces recorded interprovincial migratory losses.

According to preliminary population estimates, there were more deaths than births in all the Atlantic provinces, including Prince Edward Island this year. Thus, the international migratory growth there was the main population growth factor, with some interprovincial migratory increase. The only exception remains Newfoundland and Labrador, where international migratory growth (+0.4%) did not offset the decrease attributable to a negative natural increase (-0.3%) and to interprovincial migratory losses (-0.9%).

In the territories, natural increase was a more substantial source of population growth, primarily on account of higher fertility levels. Nunavut’s natural increase (+1.9%)—by far the highest in Canada—was behind most of this territory’s population growth. In the Northwest Territories, strong natural increase (+0.8%) and positive international migratory growth (+0.3%) were, however, offset by a considerably negative interprovincial migratory growth (-1.3%). Yukon was the only territory with an international migratory growth that matched natural increase (+0.6% each).

Data table for Chart 1.6

| Natural increase | International migratory increase | Interprovincial migratory increase | Population growth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate (%) | ||||

| Canada | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| N.L. | -0.3 | 0.4 | -0.9 | -0.8 |

| P.E.I. | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| N.S. | -0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| N.B. | -0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Que. | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Ont. | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Man. | 0.4 | 1.4 | -0.7 | 1.2 |

| Sask. | 0.5 | 1.3 | -0.8 | 1.0 |

| Alta. | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.6 |

| B.C. | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Y.T. | 0.6 | 0.6 | -0.6 | 0.6 |

| N.W.T. | 0.8 | 0.3 | -1.3 | -0.3 |

| Nvt. | 1.9 | 0.1 | -0.3 | 1.7 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | ||||

A growing share of immigrants settle in Ontario

Ontario attracted 44.3% of new immigrants in 2018/2019, up compared with 43.7% the previous year. Over the last year, 22.5% of immigrants settled in one of the three Prairie provinces. This proportion was almost two and a half times higher than that observed 20 years ago (9.4% in 1998/1999). The share of new immigrants settling in Quebec in 2018/2019 dropped slightly to 14.3%, compared with 15.8% in 2017/2018.

The estimated number of immigrants by province and territory is based on their intended province or territory of residence, as collected by IRCC. This also applies to the calculation of international migratory growth and provincial and territorial population growth.

In the last year, the share of immigrants received by Ontario (44.3%) largely exceeded its demographic weight (38.8%). With a narrower gap, this was also the case for each Western Canada province, as well as Prince Edward Island. Moreover, there has been an increase in the proportion of immigrants received by the Atlantic provinces (4.9%), a level three times higher than 20 years ago (1.7% in 1998/1999).

Aside from the Prairies, all provinces posted an increase rarely or never observed in the number of non-permanent residents in 2018/2019. Among other things, Quebec posted a record gain of 46,930 non-permanent residents, even surpassing the number of new immigrants for the first time since 1971/1972.Note British Columbia also posted a record high in the number of non-permanent residents (+27,243), as did the Atlantic provinces (except Newfoundland and Labrador). The increase in the number of non-permanent residents was one of the highest in Ontario (+81,186).

Data table for Chart 1.7

| Year ending June 30 | Atlantic provinces | Quebec | Ontario | Manitoba | Saskatchewan | Alberta | British Columbia | Territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||||||

| 1999 | 1.7 | 16.0 | 53.1 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 6.5 | 19.8 | 0.1 |

| 2004 | 1.4 | 18.6 | 53.5 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 7.2 | 15.4 | 0.1 |

| 2009 | 2.7 | 19.0 | 43.0 | 5.3 | 2.4 | 10.3 | 17.3 | 0.1 |

| 2014 | 2.8 | 19.3 | 38.0 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 0.2 |

| 2019 | 4.9 | 14.3 | 44.3 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 0.2 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | ||||||||

The Maritimes, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia gain in their exchanges with the other provinces

At the provincial and territorial level, population growth is also the result of interprovincial migratory exchanges.

Aside from Newfoundland and Labrador, and contrary to the historical trend, more people are moving to the Maritimes to settle there, compared with the opposite in recent years. Three to four consecutive years of positive interprovincial migration had not been observed since the mid-1970s for New Brunswick, the early 1980s for Nova Scotia, and the turn of this century for Prince Edward Island. Thus, according to preliminary population estimates for 2018/2019, Nova Scotia gained 3,306 people through its migratory exchanges with the other provinces and territories, particularly with Ontario, British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador. Preliminary interprovincial gains stood at 606 individuals in New Brunswick, and 129 in Prince Edward Island.

Ontario (+11,731) and British Columbia (+6,111) had the highest interprovincial migratory gains in 2018/2019. Ontario’s interprovincial migratory increase was positive over the past four years, following 12 years of decrease.

Alberta experienced interprovincial migratory gains of 5,542 people in 2018/2019, following a three-year decline. In fact, after posting the highest interprovincial migratory gains for five consecutive years, from 2010/2011 to 2014/2015, Alberta recorded the biggest losses in 2015/2016 (-15,108) and 2016/2017 (-15,559), then diminishing considerably in 2017/2018 (-3,247). Alberta’s positive migratory growth was mainly due to the province’s greater capacity to attract, despite the increase in the number of out migrants.

In the rest of Canada, Manitoba (-9,246) and Saskatchewan (-9,688) posted the highest interprovincial migratory losses since the early 1990s. Also rare are the years in which Quebec has seen such low interprovincial migratory losses (-3,049) since 1951.

Population growth and economic growth are often interrelated. For example, Canada’s interprovincial migration flows can be either a source or a result of economic conditions, including variations in employment, unemployment or the price of certain raw materials. Therefore, the fact that Alberta drew more individuals from other provinces than Albertans who left the province could be related to once-again favourable economic conditions in the province. Similarly, Alberta’s interprovincial migratory losses in 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 could be related to a decline in economic activities in that province at the time. In 2016, Alberta posted the highest unemployment rate in the last 20 years, as well as job and wage losses in most economic activity sectors.Note In contrast, employment rose by 38,600 between July 2017 and July 2018, and by 19,200 the following year, while the unemployment rate dropped 1.0 percentage point to 6.7% in July 2018 and remained stable the following year.Note However, the last two years were marked by substantial decrease in interprovincial losses.

Data table for Chart 1.8

| Provinces and territories | In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | |||

| N.L. | 5,205 | -9,706 | -4,501 |

| P.E.I. | 3,922 | -3,793 | 129 |

| N.S. | 17,324 | -14,018 | 3,306 |

| N.B. | 11,945 | -11,339 | 606 |

| Que. | 24,604 | -27,653 | -3,049 |

| Ont. | 77,281 | -65,550 | 11,731 |

| Man. | 10,351 | -19,597 | -9,246 |

| Sask. | 13,919 | -23,607 | -9,688 |

| Alta. | 65,778 | -60,236 | 5,542 |

| B.C. | 55,612 | -49,501 | 6,111 |

| Y.T. | 1,518 | -1,744 | -226 |

| N.W.T. | 1,701 | -2,299 | -598 |

| Nvt. | 1,327 | -1,444 | -117 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | |||

The largest migration flows involve exchanges between Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia

The 30 largest migration flows are shown in the pie chartNote below, in which each province or territory is assigned a colour. Migration origins and destinations are represented by the circle’s segments. Flows are the same colour as their origin, the width indicates their size and the arrow their direction.

Data table for Chart 1.9

Origins and destinations are represented by the circle’s segments. Each province or territory is assigned a colour. Flows have the same colour as their origin, the width indicates their size and the arrow their direction. Indicates the absolute number (thousands) of interprovincial in-migrants and out-migrants. The 30 most important flows are shown.

| Origin | Destination | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.L. | P.E.I. | N.S. | N.B. | Que. | Ont. | Man. | Sask. | Alta. | B.C. | Y.T. | N.W.T. | Nvt. | |

| N.L. | Note ...: not applicable | 180 | 1,480 | 562 | 266 | 2,700 | 150 | 222 | 3,040 | 913 | 19 | 89 | 85 |

| P.E.I. | 112 | Note ...: not applicable | 563 | 264 | 160 | 1,817 | 48 | 44 | 486 | 292 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| N.S. | 536 | 606 | Note ...: not applicable | 1,979 | 1,055 | 4,903 | 173 | 246 | 2,724 | 1,273 | 57 | 209 | 257 |

| N.B. | 299 | 288 | 2,163 | Note ...: not applicable | 1,725 | 3,602 | 188 | 164 | 1,962 | 897 | 20 | 18 | 13 |

| Que. | 178 | 98 | 658 | 1,381 | Note ...: not applicable | 18,401 | 341 | 289 | 2,818 | 3,143 | 97 | 162 | 87 |

| Ont. | 2,001 | 1,646 | 6,123 | 3,931 | 13,291 | Note ...: not applicable | 3,213 | 2,347 | 16,555 | 15,443 | 385 | 208 | 407 |

| Man. | 103 | 73 | 493 | 213 | 799 | 6,811 | Note ...: not applicable | 1,917 | 4,892 | 4,074 | 77 | 70 | 75 |

| Sask. | 93 | 47 | 347 | 241 | 712 | 6,027 | 1,583 | Note ...: not applicable | 9,930 | 4,390 | 40 | 130 | 67 |

| Alta. | 1,489 | 485 | 2,745 | 2,035 | 3,095 | 16,949 | 2,282 | 6,122 | Note ...: not applicable | 24,061 | 277 | 557 | 139 |

| B.C. | 232 | 451 | 2,263 | 1,211 | 3,145 | 14,804 | 2,264 | 2,325 | 22,176 | Note ...: not applicable | 385 | 172 | 73 |

| Y.T. | 30 | 16 | 129 | 48 | 92 | 246 | 9 | 111 | 345 | 612 | Note ...: not applicable | 57 | 49 |

| N.W.T. | 67 | 14 | 151 | 39 | 99 | 433 | 56 | 112 | 716 | 428 | 116 | Note ...: not applicable | 68 |

| Nvt. | 65 | 18 | 209 | 41 | 165 | 588 | 44 | 20 | 134 | 86 | 45 | 29 | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. |

|||||||||||||

Over the past year, the largest interprovincial migration flow was from Alberta to British Columbia (24,061 migrants). The second largest interprovincial migration flow in Canada was in the opposite direction, i.e., from British Columbia to Alberta: 22,176 migrants. Taking into account these exchanges between the two provinces resulted in gains of 1,885 people for British Columbia. These gains in British Columbia at the expense of Alberta were also nearly four times lower than last year (+6,778). This decrease partly explains that the net in British Columbia, all provinces of origin combined, was two times less (+6,111) than in 2017/2018 (+13,989). Moreover, more people left Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador for Alberta in 2018/2019 (+17,862) compared with 2017/2018 (+15,215). Since Alberta has not incurred any migration losses with Ontario over the past year, the result of these migrations was a net interprovincial gain for Alberta.

The third largest interprovincial migration flow in Canada came from Quebec to Ontario (18,401). This often large-scale flow is mainly due to the proximity of the two provinces and their demographic weight.

In relative terms (expressed as ratesNote ), the largest interprovincial migration flows among provinces were from Prince Edward Island to Ontario (+1.2%), from Saskatchewan to Alberta (+0.8%), from Newfoundland and Labrador to Alberta, and from Alberta to British Columbia (+0.6% each).

Notes

- Date modified: