Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series

Canada’s Black population: Education, labour and resilience

Skip to text

Text begins

Introduction

This booklet is part of a series of documents released in conjunction with the United Nations’ International Decade for People of African Descent (2015 to 2024) and Black History Month. It aims to provide insight into some of the key socioeconomic characteristics of Canada’s Black communities.

The first booklet in this series titled “Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview”, was released in February 2019 and highlighted both the demographic characteristics and diversity of this population. Among others, the booklet demonstrated that the Black population which represents close to 1.2 million people in 2016, is not only diverse, but also young and growing in size.

To obtain a more comprehensive portrait of this population, this second booklet presents indicators related to education, employment, income, family structures and perceptions using data from the census and the General Social Survey (GSS).

This booklet first looks at the education characteristics of the Black population, which are associated with several other aspects of their socioeconomic situation. An analysis of the highest level of educational attainment was disaggregated by sex and immigrant status, followed by data on the educational expectations and aspirations of young Black individuals.

The Black population’s labour market outcomes are the focus of the second part of this booklet. In addition to employment, unemployment and income indicators, there are also data presented on work experiences, including their perceived experience of discrimination and their level of satisfaction.

Information on coping with life’s difficulties and perceptions of the future are presented in the third part of this booklet.

Some socioeconomic indicators are then presented for selected census metropolitan areas (CMA), which show that, far from being homogeneous, the situation of the Black population varies greatly from one part of the country to another.

Population of interest

There are many different ways to define and measure the population of interest. It is a population that comprises a diverse community of people in terms of history, ethnic and cultural origins, place of birth, religion, and languages.

For this portrait, the population of interest refers to people who self-identified as “Black” in the population group question in the Census of Population. Since the 1996 Census, “Black” is one of the population groups listed on the census questionnaire. Respondents can select one or more of the listed population groups, or specify another group. With the exception of respondents who identified as belonging to both “Black” and “White” population groups, multiple responses are excluded from this analysis.

In the General Social Survey, the population of interest also refers to those who selected “Black” to a similar population group question.

Given the focus and scope of this booklet, the population who did not self-identify as “Black” was regrouped into a single reference category labelled as “the rest of the population”. This approach, used to put in perspective the specificities of the Black population through comparisons, does not presume that the “rest of the population” is a homogeneous entity.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population 2A-L questionnaire.

Description for questionnaire

The image shows question 19 on population groups from the 2016 Census of Population 2A-L questionnaire. Respondents were asked 'Is this person:' and were instructed to mark one or more of the 11 mark-in categories, or to specify another group in the write-in space, if applicable. The list of mark-in categories are the following:

- White

- South Asian (e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, etc.)

- Chinese

- Black

- Filipino

- Latin American

- Arab

- Southeast Asian (e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai, etc.)

- West Asian (e.g., Iranian, Afghan, etc.)

- Korean

- Japanese

- Other - specify

In 2016, close to 7 in 10 Black adults had a postsecondary diploma

The highest level of educational attainment among the Black population varied by sex and immigrant status.

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Total Black population | ||

| Total — Highest certificate, diploma or degree | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No certificate, diploma or degree | 10.3 | 10.9 |

| Secondary (high) school diploma or equivalency certificate | 19.0 | 26.5 |

| Apprenticeship or trades certificate or diploma | 9.8 | 11.1 |

| College, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma | 28.6 | 19.7 |

| University certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| University certificate, diploma or degree at bachelor level or above | 27.5 | 27.7 |

| Immigrants | ||

| Total — Highest certificate, diploma or degree | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No certificate, diploma or degree | 11.7 | 10.8 |

| Secondary (high) school diploma or equivalency certificate | 18.4 | 24.7 |

| Apprenticeship or trades certificate or diploma | 11.1 | 11.4 |

| College, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma | 28.5 | 18.6 |

| University certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| University certificate, diploma or degree at bachelor level or above | 25.4 | 29.8 |

| Non-immigrants | ||

| Total — Highest certificate, diploma or degree | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No certificate, diploma or degree | 6.1 | 11.1 |

| Secondary (high) school diploma or equivalency certificate | 21.0 | 32.9 |

| Apprenticeship or trades certificate or diploma | 6.4 | 10.7 |

| College, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma | 31.1 | 24.1 |

| University certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 4.0 | 2.8 |

| University certificate, diploma or degree at bachelor level or above | 31.4 | 18.4 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. | ||

The differences are notable among those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Among the non-immigrant population, 18% of Black men had a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2016, compared to 31% of Black women (a similar situation in the rest of the population).

The immigrant population is generally more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or higher than the non-immigrant population. It was the opposite for Black women. In 2016, 25% of Black immigrant women had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 31% of Black non-immigrant women.

This can be partly explained by immigrant admission categories. It is most notable among Black immigrants from Africa where a higher proportion of men than women were chosen, in part for their skills and qualifications, such as educational attainment.

| Black women | Women in the rest of the population | Black men | Men in the rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Total population | 27.5 | 32.7 | 27.7 | 26.7 |

| Immigrants | 25.4 | 42.8 | 29.8 | 42.3 |

| Non-immigrants | 31.4 | 28.6 | 18.4 | 21.1 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. | ||||

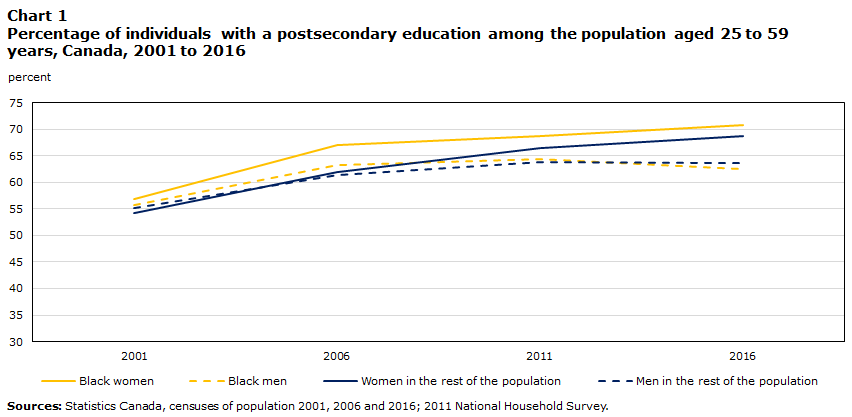

The proportion of Black women with a postsecondary education has increased over time

Data table for Chart 1

| Black women | Black men | Women in the rest of the population | Men in the rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2001 | 56.9 | 55.8 | 54.3 | 55.1 |

| 2006 | 67.1 | 63.3 | 61.9 | 61.4 |

| 2011 | 68.8 | 64.5 | 66.4 | 63.9 |

| 2016 | 70.7 | 62.6 | 68.6 | 63.6 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, censuses of population 2001, 2006 and 2016; 2011 National Household Survey. | ||||

In general, the proportion of Canadians with a postsecondary education has increased since 2001. This increase was more pronounced among women than among men, for both the Black population and the rest of the population.

Since 2011, however, there has been a decline in the proportion of Black men with a postsecondary education, while the proportion remained stable for men in the rest of the population.

Most Black youth would like to obtain a university degree, but proportionally, they are less likely to think that they will obtain one

In 2016, although 94% of Black youth aged 15 to 25 said that they would like to get a bachelor’s degree or higher, 60% thought that they could.

Data table for Chart 2

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Would like to obtain a university degree | 93.9Note * | 85.6 | 102.3 | 82.4 | 79.9 | 84.8 |

| Think they will obtain a university degree | 59.9 | 43.5 | 76.2 | 78.8 | 76.1 | 81.4 |

|

||||||

Some authors suggest that students’ perceptions about their educational attainment potential may be influenced, among other things, by certain teachers and other professionals in the school system (James and Turner 2017; Fitzpatrick et al. 2015; Burgess and Greaves 2013; James 2000).

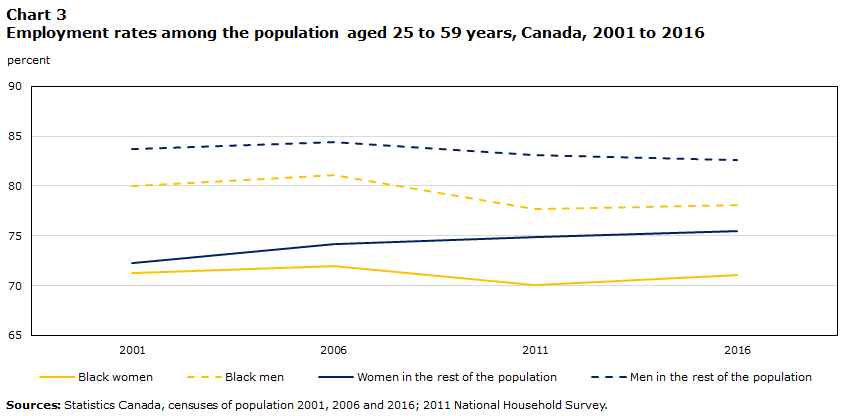

Black men saw both their employment rates fall and their unemployment rates rise over time

Data table for Chart 3

| Black women | Black men | Women in the rest of the population | Men in the rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2001 | 71.3 | 80.0 | 72.3 | 83.7 |

| 2006 | 72.0 | 81.1 | 74.2 | 84.4 |

| 2011 | 70.0 | 77.7 | 74.9 | 83.1 |

| 2016 | 71.0 | 78.1 | 75.5 | 82.6 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, censuses of population 2001, 2006 and 2016; 2011 National Household Survey. | ||||

The employment rate of Black people aged 25 to 59 is lower than in the rest of the population. In 2016, the employment rate was 78.1% for Black men and 71.0% for Black women, compared with 82.6% and 75.5%, respectively, for their counterpart in the rest of the population.

Between 2001 and 2011, the gap in the employment rate between the Black population and the rest of population increased, for both women and men. However, this gap decreased slightly between 2011 and 2016.

Data table for Chart 4

| Black women | Black men | Women in the rest of the population | Men in the rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2001 | 10.2 | 9.1 | 6.0 | 6.3 |

| 2006 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| 2011 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 6.2 |

| 2016 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 5.8 | 6.7 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, censuses of population 2001, 2006 and 2016; 2011 National Household Survey. | ||||

During this period, the unemployment rates among the Black population were consistently higher than in the rest of the population.

This was the case even at higher levels of education. For example, among those with a postsecondary education in 2016, the unemployment rate for the Black population was 9.2%, compared to 5.3% for those in the rest of the population.

These gaps between the groups in employment and unemployment rates persist even after controlling for the effects of various socioeconomic factors, suggesting that other factors, not measured in the census, may be at work (Houle 2020).

Canadian studies (e.g., Oreopoulous 2011 and Eid 2012) used fictitious resumes and found that, among other things, “racialized” candidates were significantly less likely to be interviewed than other candidates with the same levels of qualification and equivalent experience.

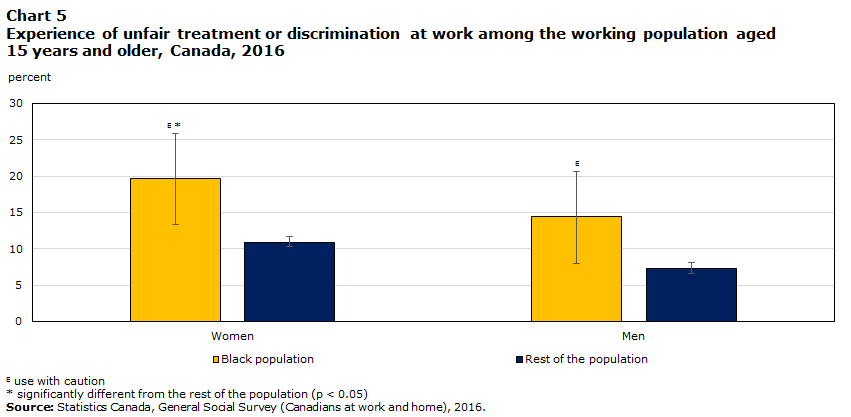

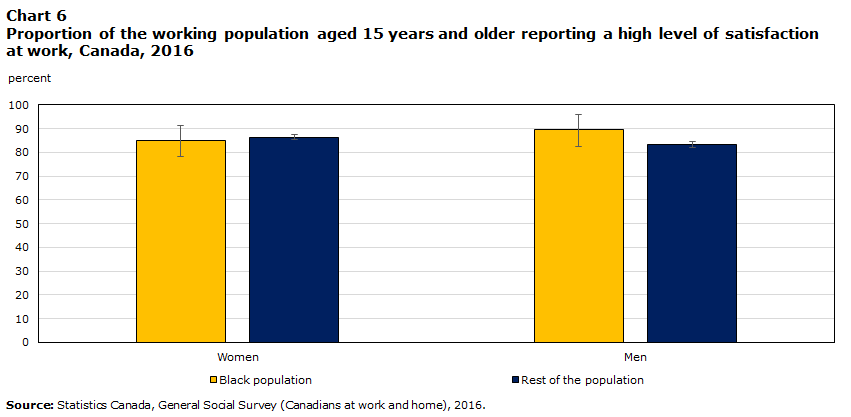

Despite hardships in the workforce, Black individuals were generally satisfied with their jobs

Data table for Chart 5

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Black population | 19.6Note E: Use with caution Note * | 13.4 | 25.9 | 14.4Note E: Use with caution | 8.1 | 20.8 |

| Rest of the population | 10.9 | 10.1 | 11.7 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 8.0 |

E use with caution

|

||||||

According to data from the 2016 GSS, Black employees aged 15 or over, were more likely than their counterparts in the rest of the population to report having experienced unfair treatment or discrimination at work in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Data table for Chart 6

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Black population | 85.0 | 78.6 | 91.3 | 89.5 | 82.7 | 96.3 |

| Rest of the population | 86.3 | 85.2 | 87.3 | 83.4 | 82.3 | 84.6 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey (Canadians at work and home), 2016. | ||||||

At the same time, the majority of the Black population reported a high level of job satisfaction, with 85% of Black women and 90% of Black men.

Additionally, 79% of employed Black individuals felt a strong sense of belonging to the organization for which they worked, similar to results in the rest of the population (82%).

Friends are often a source of support in the workplace for the Black population. About 3 in 10 Black employees reported having many good friends at work, and around 2 in 10 reported having having one ot two good friends at work. These results were similar in the rest of the population.

Many inequalities that are observed in society may persist even when the structural conditions that created them have changed (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2016).

The gap in median annual wages between Black men and their counterparts in the rest of the population has persisted over time

Data table for Chart 7

| Black women | Black men | Women in the rest of the population | Men in the rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||||

| 2000 | 32,552 | 40,214 | 33,854 | 52,083 |

| 2005 | 33,188 | 40,116 | 35,094 | 52,557 |

| 2010 | 36,358 | 41,911 | 38,961 | 54,501 |

| 2015 | 35,663 | 41,146 | 39,654 | 55,801 |

|

||||

While median annual wages increased in the general population from 2000 to 2015, it remained relatively stable for Black men, at approximately $40,000.

In 2000 and 2005, Black women earned median annual wages similar to those of women in the rest of the population. Since then, however, the gap between the two groups of women has increased.

Among immigrant women, the wage gaps between Black women and women in the rest of the population was very low ($1,300 difference at most, favouring Black women). Conversely, among those born in Canada, the annual wages of Black women were approximately $3,500 to $7,000 lower than that of women in the rest of the population.

About 1 in 5 Black adults live in a low-income situation

Data table for Chart 8

| Black population | Rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 2015 | 20.7 | 12.0 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population 2016. | ||

In 2016, 21% of the Black population aged 25 to 59 lived in a low-income situation, compared with 12% of their counterparts in the rest of the population.

In 2016, 27% of Black children were living in a low-income situation, compared to 14% of children in the rest of the population.

In 2016, one-third of Black adults lived with children at home

| Black population | Rest of the population | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| In a couple without children | 8.7 | 25.9 |

| In a couple with children | 33.9 | 36.0 |

| In a lone-parent family | 19.3 | 7.9 |

| Persons in multigenerational households | 8.5 | 5.7 |

| Living with others (relatives or non-relatives) | 17.3 | 10.7 |

| Living alone | 12.3 | 13.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. | ||

In Canada, close to 2 in 10 Black individuals were in lone-parent families.

Regarding the household living arrangements of individuals, living in a couple with children (34%) was the most common situation for the Black population, a result similar to what is observed in the rest of the population. However, the proportion of persons in a lone-parent family was at least two times higher in the Black population than in the rest of the population (19% and 8%, respectively). Among the Black population, nearly 70% of these lone-parents were women.

Black immigrant women have a higher rate of lone parenthood than other immigrant women. In 2016, nearly 30% of Black immigrant women aged 25 to 59 were lone-parents. This was 20 percentage points higher among women in the rest of the immigrant population.

In 2016, Black lone-parents were more likely to be living in a low-income situation (34%) compared with lone-parents in the rest of the population (26%).

Many parental characteristics—such as immigrant status, single parenthood, unemployment, low education or low wages—may be associated with children and youth living in poverty (Lichter and Eggebeen 1994; Thomas 2011).

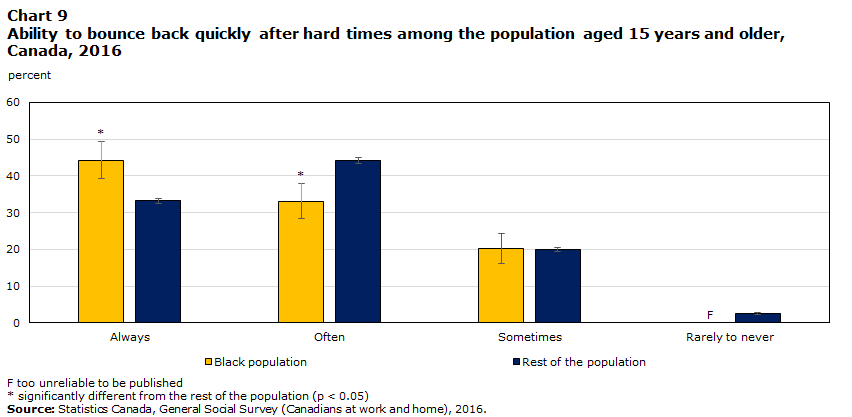

Black individuals demonstrated strong levels of resilience, even when faced with hard times

In 2016, 44% of Black individuals said they were “always” able to bounce back quickly after hard times, compared to 33% among the rest of the population.

Data table for Chart 9

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Always | 44.2Note * | 39.2 | 49.2 | 33.3 | 32.6 | 33.9 |

| Often | 33.1Note * | 28.4 | 37.8 | 44.2 | 43.5 | 44.9 |

| Sometimes | 20.4 | 16.3 | 24.4 | 20.1 | 19.5 | 20.7 |

| Rarely to never | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

F too unreliable to be published

|

||||||

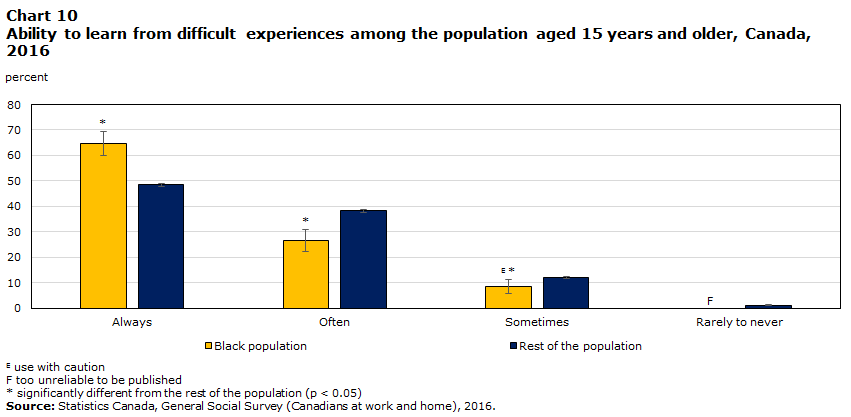

Resilience can be defined as the “ability to form a successful adaptation in the face of obstacles and adversity” (Seiler, Shamonda and Thompson 2011).

A key to resilience is how individuals make sense of negative experiences (Seiler, Shamonda and Thompson 2011). After difficult experiences, 65% of the Black population felt that they “always” learned something from those experiences compared with 48% in the rest of the population.

Data table for Chart 10

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Always | 64.7Note * | 59.9 | 69.5 | 48.4 | 47.6 | 49.1 |

| Often | 26.5Note * | 22.1 | 30.9 | 38.3 | 37.6 | 39.0 |

| Sometimes | 8.5Note E: Use with caution Note * | 5.7 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 12.6 |

| Rarely to never | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

|

||||||

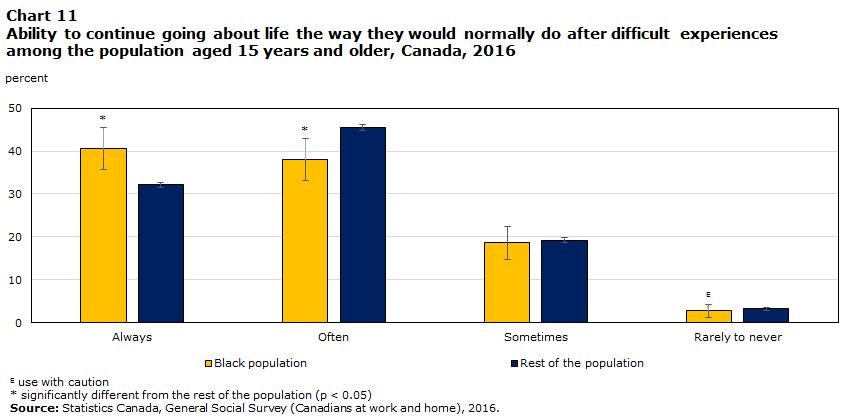

Compared with the rest of the population, Black individuals were more likely to report that, after difficult experiences, they were “always” able to continue going about their life as they normally would (41% vs 32%).

Data table for Chart 11

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Always | 40.7Note * | 35.7 | 45.6 | 32.1 | 31.4 | 32.8 |

| Often | 38.1Note * | 33.2 | 42.9 | 45.5 | 44.8 | 46.3 |

| Sometimes | 18.6 | 14.7 | 22.5 | 19.2 | 18.6 | 19.7 |

| Rarely to never | 2.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.1 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

E use with caution

|

||||||

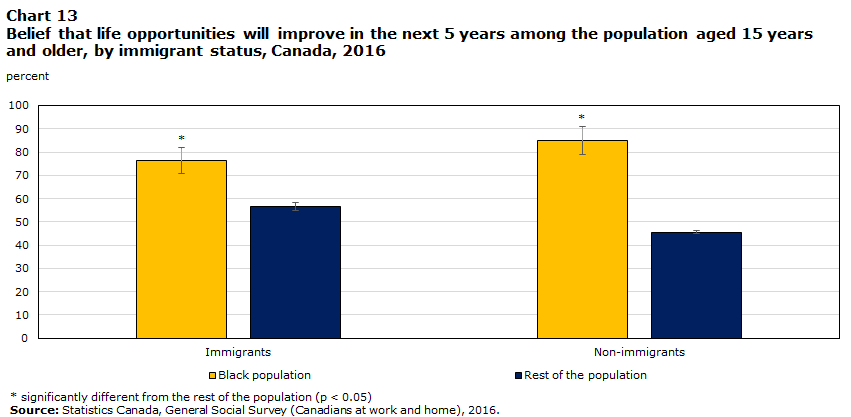

The perceived future looks bright for most of the Black population

Data table for Chart 12

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Standard of living of household | 63.1Note * | 58.0 | 68.1 | 55.8 | 55.0 | 56.5 |

| Educational opportunities | 81.8Note * | 77.9 | 85.7 | 76.0 | 75.4 | 76.6 |

| Employment opportunities | 75.1Note * | 70.7 | 79.5 | 54.8 | 54.1 | 55.5 |

| Opportunities to acquire assets | 58.5Note * | 53.5 | 63.5 | 44.5 | 43.8 | 45.3 |

|

||||||

In 2016, the majority of the Black population ranked their standard of living, educational and employment opportunities, and opportunities to acquire assets as better than those of their parents.

Most notably, compared with the rest of the population (55%), more Black individuals (75%) felt that their employment opportunities were better than those of their parents.

Also, among the Black population, 76% of the immigrants and 85% of the non-immigrants felt that their life opportunities would improve in the next five years. These proportions were significantly higher than for the rest of the population, where 57% of the immigrants and 46% of the non-immigrants felt that their life opportunities would improve.

Data table for Chart 13

| Black population | Rest of the population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Immigrants | 76.4Note * | 70.9 | 81.8 | 56.5 | 54.7 | 58.3 |

| Non-immigrants | 85.0Note * | 79.1 | 90.9 | 45.6 | 44.9 | 46.4 |

|

||||||

Geographical highlights

Below is a quick overview of some education, labour and income characteristics for the population aged 25 to 59, as well as the prevalence of low-income for children under the age of 15, for eight selected census metropolitan areas (CMAs) across Canada. In 2016, about 8 in 10 Black people lived in these CMAs.

Halifax

The unemployment rate for Black men was about two and a half times higher than the rate for men in the rest of the population of this region.

Montréal

Just under one in five Black children lived in a low-income household, lowest proportion among these eight CMAs.

Ottawa-Gatineau

Four in 10 Black men held at least a bachelor’s degree, similar to their male counterparts in this region, however there was a wide gap in terms of median annual wages.

Toronto

Two in 10 Black men held a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to about 4 in 10 of men in the rest of the population of this region.

Winnipeg

Black men were more likely to have at least a bachelor’s degree than other men of this region.

Calgary

A wide gap in terms of median annual wages between both Black men and women and their counterparts living in this region.

Edmonton

A wide gap in terms of median annual wages between Black men and other men living in this region.

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016.

Halifax—6,385 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 26.9 | 40.8 |

| Men | 26.1 | 32.3 |

Both men and women in the Black population were less likely than their counterparts in the rest of the population to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, but the gap was more pronounced for women (14 percentage points).

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 11.2 | 4.9 |

| Men | 14.1 | 5.7 |

The unemployment rate for Black men was two and a half times higher than that for men in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 31,727 | 39,563 |

| Men | 35,747 | 55,340 |

There was a gap of $20,000 between median annual wages of Black men and that for the other men of this region. For women, the gap was not as large ($8,000).

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 38.5 | 15.9 |

The percentage of Black children living in a low-income situation in Halifax was 38.5%—more than double the percentage for the rest of the population.

Montréal—129,185 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 26.5 | 36.2 |

| Men | 29.6 | 30.7 |

While Black men were almost as likely as men in the rest of the population to hold at least a bachelor’s degree, Black women were less likely to do so than women in the rest of the population by 10 percentage points.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 10.7 | 5.6 |

| Men | 11.4 | 6.2 |

Unemployment rates for Black women and men were nearly double those of their counterparts in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 30,710 | 39,154 |

| Men | 34,243 | 50,276 |

While median annual wages among Black women and men were similar, large gaps existed between the Black population and the rest of the population, especially for men.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 18.2 | 11.1 |

A larger proportion (18.2%) of Black children in Montréal were living in a low-income situation compared with children in the rest of the population (11.1%).

Ottawa–Gatineau—34,465 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 35.1 | 43.8 |

| Men | 40.3 | 38.3 |

Black men were more likely than their counterparts in the rest of the population to have a bachelor’s degree or higher, although it was the opposite for Black women.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 9.7 | 4.6 |

| Men | 11.1 | 5.0 |

Unemployment rates for Black women and men were more than two times higher than those for their counterparts in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 36,879 | 51,793 |

| Men | 40,762 | 63,384 |

Median annual wages were largely lower for Black women and men (by $23,000) than for their counterparts in the rest of the population, with gaps of $15,000 among women and $23,000 among men.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 29.2 | 11.7 |

Close to 30% of Black children in this region were living in a low-income situation — 17.5 percentage points higher than for children in the rest of the population.

Toronto—207,480 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 25.3 | 45.2 |

| Men | 21.9 | 41.7 |

Black men and women in this region were almost half as likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to their counterparts in the rest of the population.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 9.9 | 6.4 |

| Men | 8.9 | 5.3 |

The unemployment rate for Black women and men was about one and a half times higher than the rate for women and men in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 39,301 | 42,734 |

| Men | 43,695 | 56,648 |

The median annual wages of Black men and women were lower than those of their counterparts in the rest of the population, by close to $13,000 among men and by $3,400 among women.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 34.1 | 18.4 |

Nearly 35% of Black children in Toronto were living in a low-income situation, compared with close to 20% of children in the rest of the population.

Winnipeg—12,690 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 33.4 | 36.2 |

| Men | 35.7 | 28.7 |

Black men were more likely than men in the rest of the population to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, and Black women were only slightly less likely than other women to do so.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 7.7 | 4.6 |

| Men | 8.2 | 5.2 |

Unemployment rates for Black women and men were more than one and a half times higher than those for women and men in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 33,707 | 39,786 |

| Men | 39,581 | 52,336 |

Gaps existed in median annual wages between the Black population and the rest of the population, but the gap between Black men and men in the rest of the population was greater than the gap between Black women and women in the rest of the population.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 26.1 | 16.1 |

Compared with children in the rest of the population (16.1%), there were more Black children living in a low-income situation (26.1%).

Calgary—27,195 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 33.3 | 41.5 |

| Men | 37.0 | 37.2 |

Black men were just as likely as men in the rest of the population to hold at least a bachelor’s degree, but Black women were less likely than women in the rest of the population to do so.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 13.5 | 7.7 |

| Men | 13.1 | 8.3 |

Unemployment rates for Black women and men were more than one and a half times higher than those for women and men in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 35,131 | 48,044 |

| Men | 48,553 | 69,882 |

The gap in median annual wages between Black men and men in the rest of the population was over $20,000, and the gap between Black women and women in the rest of the population was close to $13,000.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 27.4 | 11.7 |

Nearly 3 in 10 Black children in Calgary were living in a low-income situation, compared with 1 in 10 children in the rest of the population.

Edmonton—28,240 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 26.4 | 33.3 |

| Men | 27.4 | 26.1 |

While Black men and men in the rest of the population were equally likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, Black women were less likely than their counterparts in the rest of the population to have similar educational attainment.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 12.1 | 6.3 |

| Men | 13.5 | 7.9 |

Unemployment rates for Black women and men were nearly two times higher than the rates for their counterparts in the rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 36,310 | 46,198 |

| Men | 49,514 | 72,130 |

The gap in median annual wages between Black women and women in the rest of the population was under $10,000, whereas the gap between Black men and men in the rest of the population was over $22,000.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 28.2 | 11.3 |

Three in 10 Black children were living in a low-income situation, a rate three times higher than that for children in the rest of the population.

Vancouver—14,360 Black individuals (aged 25 to 59)

Education

(Bachelor level or above)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 29.6 | 41.0 |

| Men | 26.3 | 36.7 |

Both Black women and Black men were less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to women and men in the rest of the population — a difference of about 10 percentage points.

Labour

(Unemployment rate)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 8.1 | 5.2 |

| Men | 6.7 | 4.5 |

The unemployment rate for the Black population (for both women and men) was approximately one and a half times higher than that for rest of the population.

Income

(Median annual wages)

| Black Population |

Rest of the Population |

|

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Women | 38,228 | 39,466 |

| Men | 42,961 | 55,188 |

Only a small gap existed between the median annual wages of Black women and women in the rest of the population, but the gap between Black men and men in the rest of the population was over $12,000.

Family

(Children in low-income)

| Black Children |

Children in the rest of the population |

|

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Children | 31.9 | 18.0 |

There were close to two times more Black children living in a low-income situation (31.9%), compared with children in the rest of the population.

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016.

Conclusion

This booklet presents some of the socioeconomic characteristics of the Black population in Canada, bringing to light some of the challenges that this population faces, particularly in terms of employment and income.

Compared to the rest of the population, employment rates remain low and the prevalence of low-income is more common among the Black population. Despite these challenges, Black individuals have high rates of job satisfaction and high rates of resilience.

The analysis has demonstrated that the challenges facing the Black population may present themselves differently within specific groups, such as among immigrants or women and men.

There are notable differences between immigrants and non-immigrants in terms of postsecondary education. Immigrants are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to non-immigrants. However, this relationship was the reverse for Black women, with non-immigrants being more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or higher than immigrants.

The Black population is not a homogenous one. On the contrary, it is very diverse, whether in terms of ethnic or cultural origins, places of birth, languages and religions. It is equally diverse in terms of experiences and socioeconomic characteristics, which are the subject of this booklet.

While this booklet aims to provide a brief overview of some of these experiences and characteristics, it cannot fully illustrate the diversity within, nor all the issues affecting the Black population in Canada. Studies such as “Education and labour market integration of Black youth in Canada” (released February 25, 2020) and “Changes in the socioeconomic situation of Canada’s Black population, 2001 to 2016” (to be released in spring 2020) provide a complement to, and a more in-depth analysis of the results seen in this booklet. The reader is invited to consult them, as each provides different perspectives on Black communities in Canada.

Recent Statistics Canada studies

“Changes in the socioeconomic situation of Canada’s Black population, 2001 to 2016,” by René Houle

To be released in 2020 // Catalogue no. 89-657-X

“Education and labour market integration of Black youth in Canada,” by Martin Turcotte

Release date: February 25, 2020 // Catalogue no.75-006-X

- Black youth aged 9 to 13 in 2006 were as likely as other Canadian youth to have graduated from high school in 2016.

- Young Black men and women aged 13 to 17 in 2006 were less likely to have completed a postsecondary education in 2016 than their counterparts in the rest of the population.

- Young Black men were almost twice as likely than other young men to be neither in employment, education, nor training in 2016.

“Intergenerational education mobility and labour market outcomes: Variation among the second generation of immigrants in Canada,” by Wen-Hao Chen and Feng Hou

Release date: February 18, 2019 // Catalogue no. 11F0019M, no. 418

- Education progress across generations was moderate among Black men.

- Second-generation Black individuals showed moderate educational mobility and low educational attainment among men, and low earnings for both men and women.

“Police-reported hate crime in Canada, 2017,” by Amelia Armstrong

Release date: April 20, 2019 // Catalogue no. 85-002-X

* An updated report from Juristat will be available soon.

- Hate crimes targeting the Black population remained one of the most common types of hate crimes.

- Hate crimes against the Black population were more likely to be non-violent violations.

“Violent victimization and discrimination among visible minority populations, Canada,” by Laura Simpson

Release date: April 12, 2018 // Catalogue no. 85-002-X

- Those who identified as Black were among the most likely to report experiencing discrimination.

- Many perceived their race or skin colour as a basis of their discrimination.

- Black individuals were among the least likely to report feeling that their local police were doing a good job of treating people fairly.

“Visible minority women,” by Tamara Hudon

Release date: March 3, 2016 // Catalogue no. 89-503-X

- Living alone was most common for Black seniors and for skip-generation households.

- Health and health-related fields were the top areas of study for Black women.

- Black women were most likely to be employed in sales and service.

References

Burgess, Simon and Ellen Greaves. 2013. “Test scores, subjective assessment, and stereotyping of ethnic minorities,” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 31, no. 3, p. 535–576.

Eid, Paul. 2012. “Les inégalités ‘ethnoraciales’ dans l’accès à l’emploi à Montréal : le poids de la discrimination,” Recherches sociographiques, vol. 53, no. 2, p. 415–450.

Fitzpatrick, Caroline, Carolyn Côté-Lussier, Linda S. Pagani and Clancy Blair. 2015. “I don’t think you like me very much: Child minority status and disadvantage predict relationship quality with teachers,” Youth & Society, vol. 47, no. 5, p. 727–743.

James, Carl E. and Tana Turner. 2017. Towards Race Equity in Education: The Schooling of Black Students in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto: The Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community and Diaspora, York University.

James, Carl E. 2000. “Students ‘at risk’: Stereotypes and the schooling of Black boys,” Urban Education, vol. 47, no. 2, p. 464–494.

Lichter, Daniel T., and David J. Eggebeen. 1994. “The Effect of Parental Employment on Child Poverty”, Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 633–645.

Oreopoulos, Philip. 2011. “Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with thirteen thousand resumes.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 148–171.

Seiler, Gale, Faith Shamonda and Kelly Thompson. 2011. Race, Risk, and Resilience: Implications for Community Based Practices in the Black Community of Montreal. DESTA Research Study.

Thomas, Kevin J. 2011. “Familial Influences on Poverty Among Young Children in Black Immigrant, U.S.-Born Black, and Nonblack Immigrant Families”, Demography, vol. 48, no. 2, p. 437–460.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2016. Leaving No One Behind: The Imperative of Inclusive Development. Report on the World Social Situation 2016. Available online at: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/2016/full-report.pdf.

Acknowledgements

This booklet was written by Deniz Do, in collaboration with René Houle and Martin Turcotte. The author would like to thank Jean-Pierre Corbeil, Éric Caron Malenfant, Hélène Maheux and Mireille Vézina from the Centre for Ethnocultural, Language and Immigration Statistics at Statistics Canada for their participation and their valuable input throughout the process. Many thanks to Jennifer Arkell for creating the cover page for this booklet.

The author also wishes to express gratitude to Carl E. James (professor, York University), Anne-Marie Livingstone (post-doctoral fellow, Harvard University), Malinda S. Smith (professor, University of Alberta), as well as the other members of the Working Group on Black Communities for their expert advice and guidance for this project.

- Date modified: