Juristat Bulletin—Quick Fact

Students’ experiences of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

by Marta Burczycka, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

All forms of discrimination can create an environment where people feel disrespected, excluded and potentially unsafe. In the postsecondary environment, discrimination creates barriers to full participation which may hinder the success of students (Asquith et al. 2019; Levchak 2013).

The issue of discrimination based on gender has permeated postsecondary institutions since at least the mid-twentieth century, with observers pointing out that people who identify as women continue to face discrimination in fields of study where they are underrepresented (Barthelemy et al. 2016; Reilly et al. 2015; Stratton et al. 2005). More recently, discussions on the rights of transgender people and those whose gender identity fits beyond the traditional dichotomy of “woman” and “man” have gained prominence, as members of these groups and their allies draw attention to barriers in academia and beyond (Dugan et al. 2012; Griner et al. 2017). Concurrently, people identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer have drawn attention to the inequalities they face in the postsecondary system and elsewhere (Friedman and Leaper 2010; Woodford and Kulick 2014).

For these reasons, discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting represents an important topic for research and policy work. The present study aims to describe the prevalence, characteristics, and attitudes surrounding these forms of discrimination among Canada’s 2.5 million postsecondary students (see Text box 1).Note Developed and conducted by Statistics Canada, the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) collected data from students at Canadian postsecondary schools in 2019. The survey was funded by the Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) as part of It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence.

This Juristat Bulletin—Quick Fact presents findings on the prevalence, characteristics and impacts of discrimination based on actual and perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation among students aged 18 to 24 at postsecondary institutions in the Canadian provinces (17 to 24 for students living in QuebecNote ). The context in which discriminatory behaviours occurred—where they happened, who was responsible, and who was around—gives insight into actual and perceived equality on campus. This analysis provides an indication of postsecondary school culture when it comes to issues surrounding discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation. In a separate report, Statistics Canada has released an analysis of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault among postsecondary students in the Canadian provinces (see Burczycka 2020).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Key terms

The 2019 Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) measures behaviours that occurred in the postsecondary school-related setting. Universities, colleges, CEGEPs and other postsecondary institutions are included.Note

The survey collected information on the following discriminatory behaviours based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation:

- Suggestions that a man does not act like a man is supposed to act

- Suggestions that a woman does not act like a woman is supposed to act

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their gender

- Comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are, or are assumed to be, transgender

The postsecondary school-related setting includes:

- On campus

- While travelling to or from school

- During an off-campus event organized or endorsed by the postsecondary school, including official sporting events

- During unofficial activities or social events organized by students, instructors, professors, either on or off-campus

- An employment at the school

- At a co-op or work term placement organized by the school

- Behaviours that occurred online where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school.

Campus refers to the physical building or buildings in which classes, studies, and activities take place, including (for example) residences, cafeterias, libraries, and lecture halls, as well as adjacent outdoor spaces.

End of text box 1

Almost half of students witness or experience discrimination on sexual orientation and gender identity

Close to half (47%)Note of students at Canadian postsecondary institutions witnessed or experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation (including actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation). It was more common for women (52%) than men (42%) to have either witnessed or experienced discrimination, and women were more likely to have witnessed or experienced each one of the specific kinds of behaviours included in the category (Table 1).Note

Notably, the higher prevalence of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation seen among women students mirrors findings from other studies. Women more often face many types of harmful behaviours based on gender, including unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault in the postsecondary setting (Burczycka 2020) and in Canadian society in general (Cotter and Savage 2019).

When it came to discrimination in the postsecondary setting, there was a particularly large gap between women and men who witnessed or experienced comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender. This type of discrimination was witnessed or experienced by 28% of women students, versus 15% of men. Additionally, more women than men witnessed or experienced suggestions that a woman does not act like woman is supposed to act (36% versus 25%).

Women were also more likely than men to have witnessed discriminatory behaviours in the postsecondary environment, without having personally experienced them. For instance, 25% of women students said that they had witnessed (but not experienced) suggestions that a man doesn’t act like a man is supposed to act or that a woman doesn’t act like a woman is supposed to act, compared to 22% of men. The same pattern was seen with each of the other kinds of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation, when the proportions of women and men who witnessed them were compared. Notably, it is unknown if these behaviours were more likely to have occurred in the presence of women, for example, or if women were more likely to perceive certain behaviours as discriminatory.

One in five women, one in eight men experience discrimination in the postsecondary setting

Many students indicated that they had personally experienced discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting. Women were more likely to have experienced each of the discriminatory behaviours, with the exception of being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are or are assumed to be transgender (reported by 1% of women and men, respectively).

Overall, one in five (20%) women students stated that they personally experienced discrimination in the past 12 months, representing over 200,000 individuals (Table 2).Note Among men, almost one in eight (13%) reported having this kind of experience—about 118,000 students.Note

With respect to the specific kinds of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation, 16% of women experienced comments that they didn’t act like a woman is supposed to act, while a slightly lower proportion of men (12%) experienced comments that they didn’t act like a man is supposed to act. Smaller proportions of women (3%) and men (2%) experienced being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation.

A larger difference in how women and men experienced discrimination in the postsecondary setting was seen with comments that they are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender. Almost one in ten (9%) women experienced this type of discrimination, compared to 2% of men.

Similar questions about discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation were asked by the SSPPS, a survey aimed at gathering information representative of all Canadians. Looking specifically at the workplace experiences of Canadians aged 15 and older in the provinces, findings from that study showed that 8% of women and 5% of men experienced suggestions that they did not act like a man or woman is supposed to act in the 12 months preceding that survey (Cotter and Savage 2019). Though these results are not directly comparable to information collected from students—they represent a different age group and are focussed on experiences in the workplace—these proportions show that women continue to experience higher rates of discriminatory behaviours as they move into the workforce.

Discrimination on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation experienced by one in three LGB+ students

Many students at postsecondary institutions in the Canadian provinces indicated that they were lesbian, gay, bisexual or had another sexual orientation other than heterosexual, such as pansexual or asexual (LGB+). This was the case for over 270,000 students, or 11% of all postsecondary students in the provinces, and included 14% of women, 7% of men, and 93% of gender diverse students.Note More specifically, among women, 2% identified as lesbian, 11% identified as bisexual, and 1% identified with a sexual orientation other than lesbian, bisexual or heterosexual. Among men, 3% identified as gay, 4% identified as bisexual, and 1% identified with a sexual orientation other than gay, bisexual or heterosexual. Six in ten (61%) of gender diverse students identified as bisexual.Note

Experiences of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting were prevalent among LGB+ students. Close to one-third (31%) of gay and lesbian students reported this kind of discrimination, as did 34% of bisexual students and 34% of students who reported a sexual orientation other than gay, lesbian, bisexual or heterosexual. These proportions were double that experienced by heterosexual students (15%, Table 3).

More specifically, 31% of women who identified as lesbian stated that they had experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting, as did 34% of bisexual women and 39% of women with another sexual orientation other than heterosexual. Among men, 31% of those who identified as gay or bisexual (respectively) reported discrimination of this type.Note None of these differences were found to be statistically significant.

Discrimination based on gender identity, sexual orientation experienced by other demographic groups

Discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation was reported by individuals belonging to other demographic groups. Students who reported that they lived with some form of disability were also overrepresented: a quarter (24%) indicated that they had experienced discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, compared to 13% of students who were not living with a disability (Table 3). Women students who lived with a disability had a higher prevalence of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in a postsecondary setting (26%) than women who did not have a disability (15%). Men who identified as students living with a disability also experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in larger proportions than their counterparts with no disability (19% versus 11%).

Students who indicated that they sometimes (20%) or usually (20%) wore a visible religious symbol, such as a head scarf or turban, experienced a higher prevalence of discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, compared to students who did not wear such items (16%) (Table 3). This reflected the experience of men in the postsecondary environment, more so than women students. Among women students specifically, those who sometimes (22%), usually (22%) or never (20%) wore a visible religious symbol experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in similar proportions. Among men, those who sometimes (17%) or usually (17%) wore a visible symbol associated with their religion had a slightly higher prevalence of having experienced discrimination than men who did not wear such a symbol (13%).

In contrast, students who identified as members of a visible minority group were slightly less likely to have experienced discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation (16%) than students who did not identify as a visible minority (18%) (Table 3). Women students who identified as members of a visible minority group had a slightly lower prevalence of this kind of discrimination (19%) than their counterparts who were not members of such a group (21%). Among men who were members of a visible minority group, their prevalence of this type of discrimination in the postsecondary setting (13%) was not statistically different from that of men who were not visible minorities (14%).

Discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation was as common among First Nations, Métis and InuitNote students as it was among those who were not Indigenous (19% and 17%, a difference not found to be statistically significant; Table 3). It was as common for Indigenous women students to experience this kind of discrimination as it was for their non-Indigenous counterparts (20%, respectively). Among Indigenous men, 18% experienced this type of discrimination, a proportion not found to be statistically different from that of their non-Indigenous counterparts (13%).

Most students see discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation as offensive

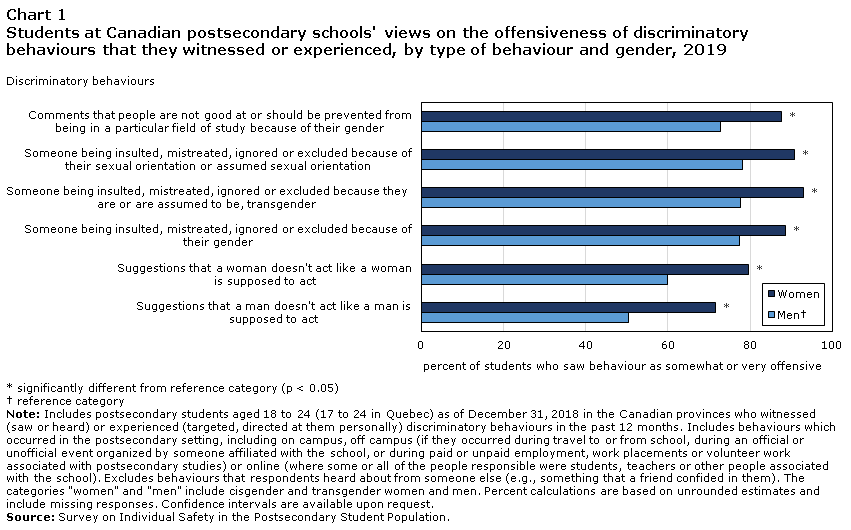

Although discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation was witnessed or experienced by many students, most considered it to be either somewhat or very offensive. Almost nine in ten (88%) women and seven in ten (73%) men who had witnessed or experienced this type of discrimination, for instance, stated that “comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular field of study because of their gender” were somewhat or very offensive (Chart 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Discriminatory behaviours | Women | MenData table Note † |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students who saw behaviour as somewhat or very offensive | ||

| Comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular field of study because of their gender | 87.5Note * | 72.8 |

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation | 90.7Note * | 78.2 |

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because they are or are assumed to be, transgender |

93.0Note * | 77.6 |

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their gender | 88.6Note * | 77.3 |

| Suggestions that a woman doesn't act like a woman is supposed to act | 79.5Note * | 59.9 |

| Suggestions that a man doesn't act like a man is supposed to act | 71.5Note * | 50.5 |

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 1 end

Nine in ten (91%) women and almost eight in ten (78%) men said that someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation was somewhat or very offensive, while similar proportions (93% of women and 78% of men) felt that way about someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because they are or are assumed to be, transgender.

Interestingly, “suggestions that a woman doesn't act like a woman is supposed to act” were somewhat or very offensive to more men (60%) than “suggestions that a man doesn't act like a man is supposed to act” (50%). Fewer women also saw this latter type of discrimination as somewhat or very offensive (72%), compared to other types.

Regardless of the specific type of discriminatory behaviour in question, women were more likely than men to consider it somewhat or very offensive.

Women who witness discrimination in the postsecondary setting are more likely to take action

In addition to being more likely to witness or experience discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting and to find it offensive, women students were also more likely than men to have done something in response when they saw these behaviours being directed at others. Over half (55%) of women said that they took some sort of action at least once in these situations, compared to 41% of men (Table 4).

Women who took action were more likely to have spoken to the person who was targeted (63%, versus 58% of men who took action) and were more likely to have spoken about it to someone outside of the school (15% versus 9%). However, when taking action, women were less likely than men to have stepped in to separate those involved (22%, versus 30% among men who intervened).

Smaller proportions of students who witnessed discrimination contacted someone in authority about it. Here, no differences were seen between women and men who took action: they were as likely to have reported the behaviour to the school (8% and 7%), spoken to someone at a school-run service (8% and 7%), and spoken to someone at a student-run service (6% and 5%).

Large proportions of both women (74%) and men (79%) stated that in at least one instance in which they had witnessed sexual orientation- and gender-based discrimination, they did nothing in response. Women were more likely than men to say that they did not take action because they felt uncomfortable (40% versus 23%), feared negative consequences for themselves or others (20% versus 13%), or worried about their personal safety (10% versus 6%). The fact that women’s actions are constrained by these types of concerns hints at broader pressures that women students may experience in the postsecondary setting.

Discrimination in learning environments, school-related employment more common for women

Discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that happened in the postsecondary context may have taken place on campus, or—if it involved a student, teacher, or happened at an event sanctioned or organized by students or the school—it may have happened in an off campus or online space (see Text box 1).

In general, seven in ten students who had experienced this kind of discrimination in the postsecondary setting said that at least one incident happened on campus. This included 73% of women and 71% of men who had experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation. Under half said that they had experienced this type of discrimination in a school-related setting off campus, including 46% of both women and men who had experienced discrimination. Less than one in five stated that discrimination had occurred in a school-related online environment (15% of women, 18% of men). None of these differences were found to be statistically significant.

Notably, women were more likely than men to have experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in two important locations. Just over half (52%) of women students who had experienced this kind of discrimination on campus said that it had happened in a learning environment such as a lecture hall or lab; this compared to 43% of men. Similarly, a considerably larger proportion of women (14%) than men (8%) who had experienced discrimination off campus said that it happened during an internship, volunteer assignment, or other type of paid or unpaid employment related to their studies. Men, on the other hand, were more likely than women to have experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in an off-campus residence (other than a fraternity or sorority; 59% of men versus 41% of women who had experienced off-campus discrimination). These differences are telling, as they suggest women more often face discrimination in formal settings directly related to their academic programs and associated work experience.

Discrimination by gender, gender identity, sexual orientation often happens with others around

Most students who experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting said that other people were around when it happened (Table 5). Seven in ten (70%) women who had experienced this kind of discrimination said that others were around in at least one instance when the behaviour took place—a slightly higher proportion than among men (66%).

While at least some of those who were around when the behaviour took place may not have been aware of what was going on, their presence suggests that the potential for intervention by others may exist in many instances. However, the majority of students who had experienced discrimination in the presence of others said that no one who was around took any action in response to what was going on: this was the case for 56% of women and 66% of men who had been discriminated against with others around.

Some students said that other people did do something in response to the acts of discrimination. Among them, many said that others confronted the perpetrator: this was the case for 74% of women and 64% of men who had experienced this type of discrimination in the presence of others who took some sort of action in response. Other common actions taken by others included creating a distraction (reported by 37% of women and 39% of men) and separating those involved (26% of women, 31% of men). Fewer students who had experienced discrimination in the postsecondary setting where others took some sort of action said that the action taken had been to tell someone in authority about what was going on (9% of women, 14% of men).

Sometimes, the actions taken by people who witnessed discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation were not intended to stop the situation or help the person being targeted. In some cases, others actually encouraged the behaviour: this was the case for 15% of women who had experienced discrimination where others took some sort of action, along with an even larger proportion of men (24%).

While most students who had experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation said that other people were present when the behaviour took place, most behaviours were perpetrated by a single person—though about a quarter of both women (23%) and men (26%) said that two or more people were always responsible. In this sense, discriminatory behaviours that occur in the postsecondary setting occasionally happen in group settings.

In general, this pattern was similar for women and men who experienced sexual orientation- or gender-based discrimination. However, there were differences when it came to the gender of perpetrators. Women were more likely than men to state that perpetrators were always men (55% of women who had experienced discrimination, compared to 38% of men). Meanwhile, men who had experienced discrimination were more likely than women to say that only women were responsible (17% versus 5%).

Peers responsible for discrimination more often than those in positions of authority

Most of the time, students who experienced sexual orientation- or gender-based discrimination said that a peer was responsible. Seven in ten women (72%) and men (73%) said that a fellow student was responsible for at least one instance, and large proportions of women (38%) and men indicated (47%) that the perpetrator was a friend or acquaintance (Table 5).

The fact that most perpetrators of discrimination were peers suggests that discrimination in the postsecondary context tends to occur outside of formal power relationships. People in authority—professors, coaches, supervisors at work and others—hold a considerable degree of power in the postsecondary setting. According to students who experienced discrimination, people in these kinds of positions were rarely responsible. That said, 12% of women who had experienced discrimination said that a professor or instructor was responsible—a larger proportion than among men (7%). Women were also more likely to state that they had been discriminated against by a teaching assistant (4% versus 2% among men). Small, but equal, proportions of women and men stated that they had experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation by a supervisor or boss at a co-op, internship or paid on-campus employment (3% and 2%, respectively).

Men face discrimination in programs of study where their gender is underrepresented

The prevalence of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation varied across university programs of study.Note Students who were enrolled in programs in where more than 60% of the students were women, where more than 60% were men and where the proportions of men and women were relatively equal had different experiences.

For men at Canadian universities, the gender composition of their field of study—that is, whether their program was made up of mostly women, mostly men, or equal proportions of both—was somewhat correlated with experiences of discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting. About one in seven (14%) men studying in programs where the majority of students were men said that they had experienced discrimination of this type (Chart 2). This was a smaller proportion than among men in programs with mostly women students, among whom 19% said that they had experienced discrimination of this type. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of men in programs with equal proportions of men and women who experienced discrimination (15%) compared to those in the other types of programs.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Gender composition of program of study | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students | ||

| Programs with a majority of women | 22.4 | 18.7Data table Note † |

| Programs with a majority of men | 27.4Data table Note † | 14.5Note * |

| Programs with relatively equal proportions of women and men | 21.7 | 15.5 |

Source: Survey of Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 2 end

Among women, 27% of those in university programs with 60% or more men stated that they had experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation. Similar proportions were noted among those in programs with mostly women (22%) and those in programs where women and men were equally represented (22%)—differences that were not found to be statistically significant.Note

Impact of discrimination greater on students’ emotional wellbeing than on academic life

Discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation can have wide-ranging and detrimental impacts on those who experience it. In an environment that ostensibly rewards talent and hard work with recognition and opportunity, discrimination can be especially destructive (Asquith et al. 2019; Levchak 2013). The SISPSP asked students about how their experiences of discrimination had impacted their emotional and mental health, as well as their academic life.

Experiences of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary context had emotional consequences for many students. For example, many women felt annoyed (59%), frustrated (54%), and angry (51%) (Table 6). These impacts were also reported by men who experienced discrimination, though they were more common among women. Notably, serious mental health impacts were similarly prevalent among women and men, including becoming anxious (14% and 11%, respectively), depressed (7% and 6%), or fearful (6% and 5%) as a result, or having experienced suicidal thoughts (2% and 3%); none of these differences were found to be statistically significant.

Notably, almost all types of negative impacts on emotional and mental health were more common for LGB+ students, compared to their non-LGB+ counterparts. This was especially pronounced when it came to serious impacts on mental health. For instance, LGB+ students who had experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation were twice or three times as likely as non-LGB+ students to have become anxious (24% versus 10%), depressed (14% versus 5%), or fearful (12% versus 4%) as a result, or to have experienced suicidal thoughts (4% versus 2%). As with non-LGB+ students, these impacts were as common among LGB+ women and LGB+ men.

Overall, relatively few students said that experiences of discrimination had an impact on their academic life. For instance, 4% of women and 3% of men who had experienced discrimination said that they had stopped going to classes as a result, and 3% of women and 2% of men had asked for extensions on assignments. However, LGB+ students who had experienced discrimination were considerably more likely to have experienced negative impacts on their academics, including having to ask for extensions on assignments (6%, versus 2% of non-LGB+ students) or dropping classes (3% versus 1%).

Less than one in ten students who experience discrimination speak about it with someone associated with the school

Relatively few students who experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation spoke about it to someone associated with the school, such as a faculty member, student support service, campus security, mental health counsellor, chaplain, or someone employed at their student residence or who was responsible for students’ wellbeing. Among women who experienced discriminatory behaviours, 7% spoke to someone associated with the school about at least one instance (compared to 5% among men) (Table 7). Of those students who did speak to someone associated with the school about what they experienced, 65% of women and 57% of men said that in at least one instance, they spoke to a resource affiliated with the school’s administration (such as a medical care centre). A smaller proportion of women (18%) said that they had spoken to someone at a student-run resource, such as a peer support group.Note

A common reason that women gave for why they chose to speak with someone associated with the school (38%) was to access mental health support. Some women who had experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation also stated that they spoke with someone associated with the school because they wished to pursue an informal resolution to the situation (19%).Note

When it came to reasons for not reporting discrimination to the school, similar proportions of women and men said that they did not do so because they did not see the incident as serious enough (65%, respectively), because they did not need help (49% of women and 46% of men who did not report), and because they had resolved the issue on their own (37% and 40%).

Other reasons included not knowing whether and how discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that happened in the postsecondary setting should be reported. These kinds of reasons were especially common among women: about one-fifth (21%) of women who did not speak to anyone at the school said they did not do so because they were not aware that this type of incident could be reported (compared to 11% of men); 15% said that they did not know who at the school could provide help (versus 8% of men). Women also worried that the school wouldn’t take them seriously (16%), as did 11% of men.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Experiences of

transgender students

While anyone can experience discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation—whether actual or perceived—research suggests that these experiences are common among the transgender population (Dugan et al. 2012; Griner et al. 2017). In the analysis that follows, transgender people are defined as anyone who does not identify as cisgender—that is, anyone who identifies with a gender other than the one that they were assigned to at birth, including individuals who do not identify with either of the binary genders, or who identify with a binary gender in addition to another gender.Note According to the SISPSP, 0.8% of postsecondary students were transgender, including 0.1% who were transgender women, 0.2% who were transgender men, and 0.4% who were gender diverse—in all, about 19,000 students.Note

Findings suggest that transgender students were considerably more likely to have experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation (Text box 2 table). Four in ten (40%) transgender students say that they had experienced discrimination of this type in the postsecondary context in the previous 12 months, compared to 17% of cisgender students.

Specifically, 27% of transgender students said that they had experienced suggestions that they do not act like a man or a woman is supposed to act; this compares to 14% of cisgender students. Similarly, 22% of transgender students stated that they had been insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their gender in a postsecondary setting—a considerably higher proportion than among their cisgender counterparts (6%). The same proportion of transgender students (22%) said that they had been insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because they were (or were perceived to be) transgender.

| Type of behaviour | CisgenderText box Note † Text box Note 1 | TransgenderText box Note 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity | 16.9 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 40.1Note * | 29.0 | 52.3 |

| Suggestions that they don't act like a man or a woman is supposed to act | 13.9 | 13.2 | 14.6 | 27.4Note * | 18.1 | 39.3 |

| Being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their gender | 5.5 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 22.2Note * | 13.7 | 33.9 |

| Comments that they are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.8 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.5 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are or are assumed to be transgender | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 22.5Note * | 13.7 | 34.6 |

|

... not applicable F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||||||

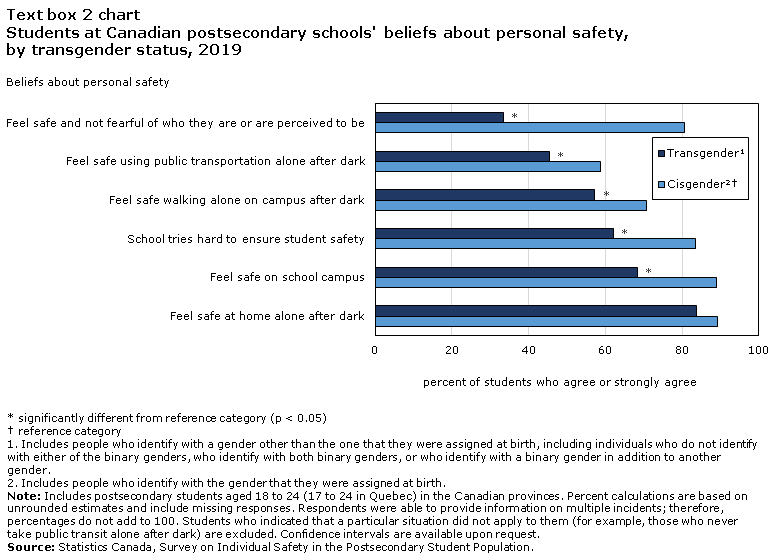

Many transgender students indicated that they did not feel safe in and around their school environment (Text box 2 chart). When asked if they felt safe and not fearful of who they were or were perceived to be, one-third (33%) said that they agreed or strongly agreed with this statement—compared to 81% of cisgender students. Transgender students were also less likely to agree or strongly agree that they felt safe when using transit alone after dark (45%, versus 59% of cisgender students), to agree or strongly agree that they felt safe walking alone on campus after dark (57% versus 71%), and to agree or strongly agree in general that they felt safe on their school’s campus (68% versus 89%). Transgender students were also less likely to agree or strongly agree that their school tries hard to ensure student safety (62% versus 83%). In contrast, most transgender students indicated that they felt safe at home alone after dark, and were as likely as cisgender students to agree or strongly agree that they felt safe in that situation (84% and 89%).

Text box 2 chart

Data table for Text box 2 chart

| Beliefs about personal safety | TransgenderText box Note 1 | CisgenderText box Note 2 Text box Note † |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students who agree or strongly agree | ||

| Feel safe and not fearful of who they are or are perceived to be | 33.5Note * | 80.6 |

| Feel safe using public transportation alone after dark | 45.4Note * | 58.7 |

| Feel safe walking alone on campus after dark | 57.2Note * | 70.8 |

| School tries hard to ensure student safety | 62.0Note * | 83.4 |

| Feel safe on school campus | 68.3Note * | 89.0 |

| Feel safe at home alone after dark | 83.7 | 89.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Text box 2 chart

End of text box 2

Students who experience discrimination based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation less likely to feel safe

In addition to questions about their experiences of discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation, postsecondary students were asked about their feelings of safety in and around their campus. Feelings of safety are an important part of how people experience the spaces around them; feeling unsafe has a negative impact on mental health and quality of life, and can dissuade people from fully engaging with the world around them (Bastomski and Smith 2016; Woodford and Kulick 2014).

Having experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation had significant impacts on students’ feelings of safety. Across all measures of personal safety in and around school, those who had not experienced discrimination were more likely to agree or strongly agree that they felt safe, while those who had these experiences were more likely to disagree or strongly disagree (Table 8). For instance, more than a quarter (27%) of students who had experienced discrimination disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe walking alone on campus after dark, compared to 14% of students who had not experienced discrimination.

Differences were seen for both women and men: women who had experienced discrimination more often disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe walking alone on campus after dark (38%) than women who had not experienced discrimination (23%). Among men, 8% of those who had experienced discrimination disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement, compared to 4% of men who had not experienced discrimination.Note In all cases—that is, across all measures of personal safety and among students that had and had not experienced discrimination—women’s responses indicated that in general, women students feel less safe in the postsecondary environment.

Summary

Close to half (47%) of students at Canadian postsecondary institutions witnessed or experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation (including actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation) in the past year. This included a larger proportion of women (52%) than men (42%). Women were also more likely to have witnessed this form of discrimination without having personally experienced it (25% versus 22%), and were more likely to have experienced it themselves (20% versus 13%).

Discrimination that happened in the postsecondary context may have taken place on campus, or—if it involved a student, teacher, or happened at an event sanctioned or organized by students or the school—it may have happened in an off-campus or online space. Women were more likely than men to have experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in two key locations, including in a learning environment such as a lecture hall or lab (52%, versus 43% of men) or during an internship, volunteer assignment, or other type of paid or unpaid employment related to their studies (14% versus 8%). This suggests women more often face discrimination in formal settings directly related to their academic programs and associated work experience.

Most women (72%) and men (73%) said that a fellow student was responsible for at least one instance of discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that they experienced in the postsecondary setting. That said, 12% of women who had experienced discrimination said that a professor or instructor was responsible—a larger proportion than among men (7%).

Women and men were similarly likely to report serious mental health impacts as a result of discrimination, such as anxiety (14% and 11%, respectively), depression (7% and 6%), and fear (6% and 5%). In addition, students who experienced discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation—especially women—said that they felt unsafe in various situations in and around campus. Despite this, relatively few students who experienced discrimination spoke about it to someone associated with the school, such as a faculty member, student support service, campus security, mental health counsellor, chaplain, or someone employed at their student residence or who was responsible for students’ wellbeing.

Experiences of discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the postsecondary setting were more common for students who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or with another sexual orientation other than heterosexual (LGB+). LGB+ students were also more likely than their non-LGB+ counterparts to experience impacts on their emotional and mental health. This kind of discrimination was also more common for transgender students.

Detailed data tables

Data source

Data are drawn from the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Population.

References

Asquith, N. L., T. Ferfolia, B. Brady and B. Hanckel. 2019. “Diversity and safety on campus @ Western: Heterosexism and cissexism in higher education.” International Review of Victimology. Vol. 25, no. 3.

Barthelemy, R. S., M. McCormick and C. Henderson. 2016. “Gender discrimination in physics and astronomy: Graduate student experiences of sexism and gender microaggressions.” Physical Review Physics Education Research. Vol. 12.

Bastomski, S. and P. Smith. 2016. “Gender, fear and public places: How negative encounters with strangers harm women.” Sex Roles. Vol. 76.

Burczycka, M. 2020. “Students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. and L. Savage. 2019. “Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Dugan, J. P., M. L. Kusel and D. M. Simounet. 2012. “Transgender college students: An exploratory study of perceptions, engagement, and educational outcomes.” Journal of College Student Development. Vol. 53, no. 5.

Friedman, C. and C. Leaper. 2010. “Sexual-minority college women’s experiences with discrimination: Relations with identity and collective action.” Psychology of Women Quarterly. Vol. 34.

Griner, S. B., C. A. Vamos, E. L. Thompson, R. Logan, C. Vázquez-Otero and E. M. Daley. 2017. “The intersection of gender identity and violence: Victimization experienced by transgender college students.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

Levchak, C. C. 2013. “An examination of racist and sexist microaggressions on college campuses.” PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa.

Reilly, A., D. Jones, C. R. Vasquez and J. Krisjanous. 2015. “Confronting gender inequality in a business school.” Higher Education Research & Development. Vol. 35, no. 5.

Stratton, T. D., M. A. McLaughlin, F. M. Witte, S. E. Fosson and L. M. Nora. 2005. “Does students’ exposure to gender discrimination and sexual harassment in medical school affect specialty choice and residency program selection?” Academic Medicine. Vol. 8, no. 4.

Woodford, M. R. and A. Kulick. 2014. “Academic and social integration on campus among sexual minority students: The impacts of psychological and experiential campus climate.” American Journal of Community Psychology.

- Date modified: