Online child sexual exploitation: A statistical profile of police-reported incidents in Canada, 2014 to 2022

by Laura Savage

Highlights

- Between 2014 and 2022, there were 15,630 incidents of police-reported online sexual offences against children and 45,816 incidents of online child pornography.

- The overall rate of police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation has risen since 2014, reaching 160 incidents per 100,000 Canadian children and youth in 2022. This rate largely reflects the rate of child pornography (125 incidents per 100,000).

- Making or distributing child pornography accounted for almost three-quarters (72%) of all incidents of child pornography between 2014 and 2022, with possessing or accessing child pornography accounting for the remaining 28% of incidents. The rate of online child pornography increased 290% between 2014 and 2022.

- Girls were overrepresented as victims for all offence types over the nine-year period. The majority of victims of police-reported online sexual offences against children were girls, particularly girls between the ages of 12 and 17 (71% of all victims).

- Incidents of non-consensual distribution of intimate images most often involved a youth victim and a youth accused. Nearly all (97%) child and youth victims between 2015 to 2022 were aged 12 to 17 years, with a median age of 15 years for girls and 14 years for boys. Nine in ten (90%) accused persons were youth aged 12 to 17. For one-third (33%) of youth victims, a casual acquaintance shared the victim’s intimate images with others.

- Excluding child pornography offences, 41% of online sexual offences against children between 2014 and 2022 were cleared (i.e., solved) by police. Incidents were more likely to be cleared if they involved multiple violations. Three-quarters (74%) of cleared incidents resulted in a charge being laid or recommended against an accused.

The Internet has become an integral part of life for most Canadians, with an estimated 99% of households having access (Frenette et al., 2020). While increased accessibility to the Internet has provided society with limitless opportunities for enhancing daily life, concerns related to online safety—particularly for children and youth—have emerged.

Advancements in technology have changed the ways that perpetrators lure and groom their victims. For example, increased accessibility to—and use of—smartphones among children and youth has made it easier for offenders to communicate with potential victims through online chatrooms and social media platforms. As digital technologies continue to evolve, there are increased opportunities for committing Internet-related crimes, including online child sexual exploitation (OCSE) (Drejer et al., 2023).

The Internet allows people to connect with others all over the world, eliminating the geographical barriers that exist with offline (contact) offending (Kloess & van der Bruggen, 2021; Leukfeldt et al., 2017). While many victims of online child sexual exploitation never meet their abusers, some incidents do lead to offline encounters where victims are sexually abused and exploited. Sometimes the sexual abuse is recorded, or livestreamed, leading to the creation of child sexual abuse material (CSAM)Note that is then shared and distributed online.

The Internet can help foster a sense of belonging among children and youth through online chatrooms (for example, Discord and Telegram) and social media platforms by connecting individuals with shared interests and values (Verduyn et al., 2017). Being born into an already connected world has changed the nature of social relationships, with children and youth spending an increasing amount of time online. Research shows that the iGeneration—that is, those born after the proliferation of the Internet (Twenge et al., 2019)—are more likely than previous generations to connect and form relationships with people they have never met offline. The potential for interacting with strangers on the Internet puts children and youth at increased risk of experiencing online child sexual exploitation (Reich et al., 2012).

Canada’s criminal laws prohibit all forms of sexual abuse and exploitation and make it illegal to possess, access, make and distribute all forms of child pornography. It is also against the law to use the Internet to communicate with a child for the purposes of facilitating the commission of a sexual offence. In 2004, Public Safety Canada—in partnership with Justice Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police—announced Canada’s National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (National Strategy) as a commitment to combat child sexual exploitation on the Internet. The National Strategy highlights the prevention efforts taken to better protect children and youth online, including increasing investigational capacity, tracking down perpetrators, enhancing public education and awareness, and supporting further research on online child sexual exploitation. A number of updates have been made to the National Strategy since 2004, and the federal government continues to work with other countries to address online child sexual exploitation at an international level.

An important pillar of the National Strategy is to support victims of online child sexual exploitation by facilitating the removal of sexual abuse material from the Internet. The Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P) is a National Strategy partner dedicated to the personal safety of all children. With funding from Public Safety Canada, C3P operates Cybertip.ca—Canada’s tipline to report child sexual abuse and exploitation online—and established Project Arachnid, a web crawler that detects child sexual abuse material and issues removal notices to electronic service providers where possible.Note Since it is estimated that most incidents are not captured by police data, data from external sources like Cybertip.ca are essential to better understand the prevalence and nature of online child sexual exploitation.

Data from self-reported victimization surveys show that only a small proportion of sexual offences come to the attention of police (Burczycka & Conroy, 2017; Cotter & Savage, 2019; Cotter, 2021), and research shows that sexual offences involving children are even less likely to be reported (Aguerri et al., 2023; Alaggia et al., 2019; Chandran et al., 2019; Taylor & Gassner, 2010). The underreporting of online child sexual exploitation can be partially attributed to the limited ability of young, dependent children to report, or even recognize, online sexual abuse. In these cases, reporting often depends on an adult bringing the offence to the attention of police. Sexual offences involving youth victims are also underreported, perhaps due to humiliation or embarrassment. Victims may also be blackmailed or threatened into silence (Chandran et al., 2019; Gerke et al., 2023). As such, it is difficult to quantify the true prevalence of online child sexual exploitation in Canada using only police-reported statistics.

Recently, Statistics Canada has published two articles related to online child sexual exploitation (see Ibrahim, 2022 and Ibrahim, 2023). Using data from both the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey and the Integrated Criminal Courts Survey (ICCS), this current Juristat article expands on previous analysis and explores the prevalence and nature of police-reported incidents of OCSE in Canada between 2014 and 2022. This Juristat article also examines how these incidents are processed by criminal courts in Canada.

This article was produced with funding support from Public Safety Canada.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Defining online child sexual exploitation

Since 2014, the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey has collected information related to online crime using a cybercrime flag.Note An incident is flagged as a cybercrime when the crime targets information and communication technology (ICT) or when the crime used ICT to commit the offence. ICT includes, but is not limited to, the Internet, computers, servers, digital technology, digital telecommunications devices, phones and networks. Crimes committed over text and through messages using social media platforms are also considered cybercrime activity.

Incidents of child pornography where a child victim is not identified by police are reported to the UCR with the most serious violation being child pornography. However, when an actual child victim is identified, the most serious violation is either sexual assault, sexual exploitation, or other sexual violations against children. In these instances, child pornography may be reported as a secondary violation.Note Police can report up to four violations per incident. This analysis includes all incidents where any violation was identified as a cyber violation. The cyber violation is not necessarily the most serious violation in the incident.Note

While there is no standard definition for online child sexual exploitation (OCSE) in the Criminal Code, this Juristat article uses the following Criminal Code violations for the analysis:

-

Online sexual offences against children

- Sexual violations against children, which involve the following Criminal Code offences: sexual interference, invitation to sexual touching, sexual exploitation, parent or guardian procuring sexual activity, householder permitting prohibited sexual activity, luring a child, agreement or arrangement (sexual offences against a child) and bestiality (in presence of, or incites, a child).

- Other sexual offences, which are Criminal Code sexual offences that are not specific to children. These offences include non-consensual distribution of intimate images, sexual assault (levels 1, 2 and 3), sexual exploitation of a person with disability, bestiality (commits, compels another person), voyeurism, incest and other sexual crimes. This analysis only includes these incidents if a victim is identified as being younger than 18.

- Online child pornography, which includes incidents excluded from the category of sexual offences against children and includes offences under section 163.1 of the Criminal Code which makes it illegal to make, distribute, possess or access child pornography.

All offences involve victims under the age of 18. The term “online child sexual exploitation” is used to refer to both categories. “Online sexual offences against children” includes “sexual violations against children” and “other sexual offences”.

End of text box 1

Section 1: Police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation

Police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation increased between 2014 and 2022

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many provinces and territories imposed lockdowns to help slow the transmission of the virus. As such, large numbers of Canadians relied on the Internet for many aspects of everyday life, including virtual schooling, remote work, and communicating and connecting with loved ones. Previously published police-reported data show a steady increase in the rates of online child sexual exploitation offences during the pandemic (Moreau, 2021; Moreau, 2022). Internet-related sexual offences represent a growing proportion of total sexual offences, likely due to increasing time being spent online (Kloess et al., 2019; Seto, 2013).

Police reported 2,492 incidents of online sexual offences against children in 2022, 139 more than in 2021. Between 2014 and 2022, there were 15,630 incidents of police-reported online sexual offences against children, translating to an average annual rate of 25 incidents per 100,000 children and youth in Canada. During this period, there were 45,816 incidents of online child pornography recorded by police, accounting for three-quarters (75%) of all OCSE offences (Table 1).

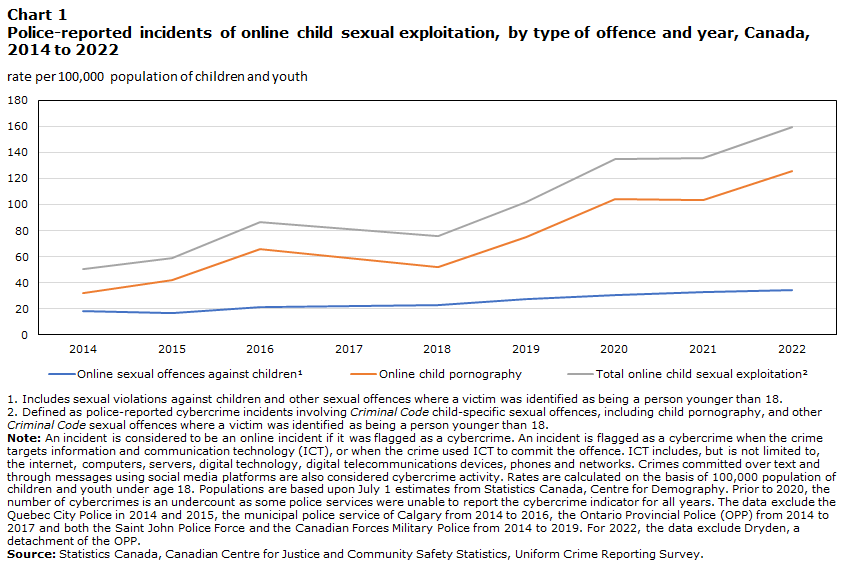

The overall rate of police-reported OCSE incidents, including both online sexual offences against children and online child pornography, has risen since 2014, reaching 160 incidents per 100,000 children and youth in 2022. This represents a 217% increase since 2014. In other words, the overall rate of this crime has more than tripled since 2014, from 50 incidents to 160 incidents per 100,000 children and youth (Chart 1). This significant increase since 2014 could reflect an actual increase in this type of crime, increased resources and training for police to better detect and understand OCSE, or a combination of both.Note

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Cyber violation | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population of children and youth | |||||||||

| Online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 1 Note 1 | 18 | 17 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 27 | 31 | 33 | 34 |

| Online child pornography | 32 | 42 | 66 | 59 | 52 | 75 | 104 | 103 | 125 |

| Total online child sexual exploitationData table for Chart 1 Note 2 | 50 | 59 | 87 | 81 | 76 | 102 | 135 | 136 | 160 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||||||||

Chart 1 end

Most recently, there was an 18% increase in the rate of online child sexual exploitation between 2021 and 2022. This was driven by a 22% increase in the rate of online child pornography—the most common offence type among OCSE crimes—from 103 incidents per 100,000 children and youth in 2021 to 125 incidents per 100,000 in 2022.

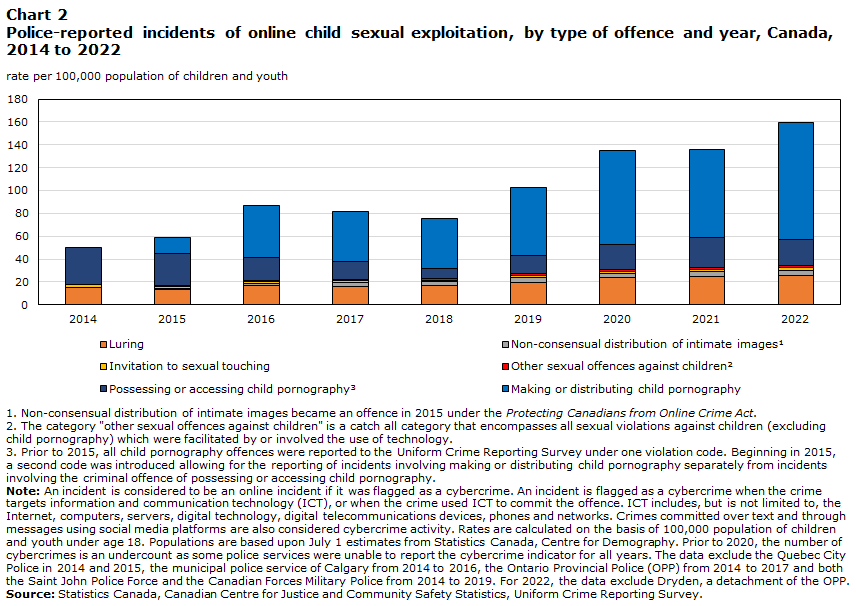

Within this offence type, the rate of making or distributing child pornography increased 33% between 2021 and 2022, while the rate of possessing or accessing child pornography fell 12% during the same period. Online child pornography offences have accounted for most incidents of OCSE since 2014 (Chart 2).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Cyber violation | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population of children and youth | |||||||||

| Online sexual offences against children | |||||||||

| Luring | 15 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 2 Note 1 | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Other sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 2 Note 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Online child pornography offences | |||||||||

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 2 Note 3 | 32 | 29 | 20 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 22 | 26 | 23 |

| Making or distributing child pornography | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 14 | 46 | 43 | 44 | 59 | 82 | 77 | 102 |

|

.. not available for a specific reference period 0 true zero or value rounded to zero

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||||||||

Chart 2 end

In 2022, the rate of police-reported online sexual offences against children reached 34 incidents per 100,000 children and youth, which was slightly higher than the rate in 2021 (33 incidents per 100,000) and double the rate recorded by police in 2014 (18 incidents per 100,000).

The following analysis will explore online sexual offences against children, including the police clearance rates of these offences, and the characteristics of both victims and persons accused of these offences. Unless otherwise noted, sections one through three do not include incidents of child pornography because there are no victim files for these incidents. Incidents of child pornography are discussed in section four.

Luring accounts for most police-reported online sexual offences against children

Online luring—the offence of communicating with a child online for the purpose of committing a sexual offence—accounts for most police-reported online sexual offences against children and youth in Canada. Some offenders may engage in online communications with a child for the purpose of arranging an in-person meeting (Kloess et al., 2019). However, many child luring offenders do not meet their victims offline and, in these situations, the sexual offence is perpetrated entirely online. Between 2018 and 2022, the C3P noted an 815% increase in reports of online luring through Cybertip.ca, Canada’s national tipline. Police-reported data show a 53% increase in luring incidents during the same period.

Between 2014 and 2022, there were 11,971 police-reported incidents of online luring, representing an average annual rate of 19 incidents per 100,000 children and youth. The rate of luring increased 69% between 2014 and 2022, from 15 incidents per 100,000 children and youth in 2014 to 26 incidents per 100,000 in 2022. In 2022, luring accounted for three-quarters (75%) of online sexual offences against children.

Between 2014 and 2022, most (82%) victims of online luring were youth (aged 12 to 17 years) and, of these, 84% were girls (Table 2). The median age for victims of luring was 13 years. This could be partially attributed to youth generally having more access to smartphones and the Internet than younger children.

Accused persons involved in online luring were also young. In incidents where an accused was identified by police, the median age of accused women and girls was 15 years and 25 years for accused boys and men.

Police-reported data generally show that victims of sexual assault are most often victimized by someone they know (Rotenberg, 2017). However, due to the anonymity provided by the Internet, children and youth victims of police-reported online sexual offences against children were most commonly victimized by a stranger (57% of child victims and 37% of youth victims). When looking specifically at luring incidents, child victims were considerably more likely than youth victims to be victimized by a stranger (62% versus 45%, respectively) (Table 3).

According to police-reported data, four in ten (39%) incidents of child luring were reported in Quebec, followed by 22% in Ontario and 12% in British Columbia. It should be noted that these are Canada’s most populous provinces. Higher proportions of incidents relative to other provinces may be partly attributed to differences in reporting practices across jurisdictions, or a greater availability of police resources to target and investigate online sexual offences against children.Note

Incidents of online sexual offences against children far more likely to be cleared when they involve multiple violations, regardless of offence type

In the UCR, the clearance status of an incident refers to whether or not the incident was “cleared” (solved) or “not cleared” (unsolved). For a criminal incident to be cleared—and for a charge to be laid or recommended—an accused must be identified.

Due to the nature of Internet-related crimes—and the ability to maintain complete anonymity using the TOR browserNote or encryption software—it is becoming increasingly more challenging for the police to identify accused persons in cases of online child sexual exploitation (Stalans & Finn, 2016; Woodhams et al., 2021). First, the absence of physical evidence often results in a lack of sufficient evidence to proceed with laying or recommending a charge against an accused. This is especially true in cases of livestreaming of child sexual abuse, which is the real-time producing, broadcasting, and viewing of child sexual abuse (Drejer et al., 2023; EPCAT International 2018). Broadcasting technologies use encryption and enhanced anonymity, making it difficult to locate viewers, track them down, and prove viewership. Resources are even more limited when the perpetrator is not in Canada. Second, different countries have different laws surrounding online child sexual exploitation. As such, offenders may choose to have their servers (the physical location of digital data) hosted in a country with less severe penalties for these offences (Ryngaert, 2023).

When looking at the clearance statusNote of online sexual offences against children reported by police between 2014 and 2022, six in ten (59%) incidents were not cleared (Table 4). Of the 41% of incidents that were cleared, seven in ten (70%) were cleared by chargeNote , while the remaining incidents were “cleared otherwise”Note (26%) or charges were recommended by police but declined by the Crown (3%).Note

Incidents were more likely to be cleared when they involved multiple violations, regardless of the offence type. Specifically, online sexual offences against children were more than twice as likely to be cleared by police when the incident involved multiple violations versus a single violation (69% versus 27%, respectively). Depending on the offence type, police may have more information about an incident (and more evidence to proceed with clearing the incident) when it involves multiple violations. Regardless of the number of violations, some offence types are more difficult to clear than others because of a lack of physical evidence. For example, a similar proportion of non-consensual distribution of intimate image incidents were cleared, regardless of whether the incident had a single (41%) or multiple (48%) violations.

Almost nine in ten incidents of invitation to sexual touching (89%) and other sexual offences against children (87%) were cleared when the incident involved multiple violations. This was much higher than the proportion of incidents cleared when there was a single violation for these offences (50% and 32%, respectively).

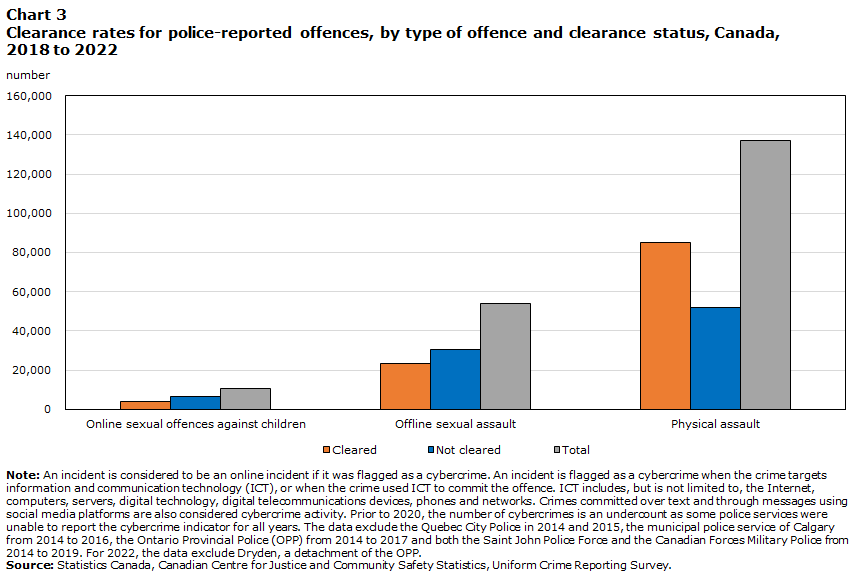

Between 2018 and 2022, the proportion of cleared incidents for online sexual offences against children (37%) was slightly lower than those for offline sexual assault (43%) and physical assault (62%) among children and youth (Chart 3).Note

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Clearance status | Online sexual offences against children | Offline sexual assault | Physical assault |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | |||

| Cleared | 3,933 | 23,422 | 85,133 |

| Not cleared | 6,719 | 30,472 | 52,160 |

| Total | 10,652 | 53,894 | 137,293 |

|

Note: An incident is considered to be an online incident if it was flagged as a cybercrime. An incident is flagged as a cybercrime when the crime targets information and communication technology (ICT), or when the crime used ICT to commit the offence. ICT includes, but is not limited to, the Internet, computers, servers, digital technology, digital telecommunications devices, phones and networks. Crimes committed over text and through messages using social media platforms are also considered cybercrime activity. Prior to 2020, the number of cybercrimes is an undercount as some police services were unable to report the cybercrime indicator for all years. The data exclude the Quebec City Police in 2014 and 2015, the municipal police service of Calgary from 2014 to 2016, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) from 2014 to 2017 and both the Saint John Police Force and the Canadian Forces Military Police from 2014 to 2019. For 2022, the data exclude Dryden, a detachment of the OPP. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 3 end

Three in ten incidents related to online sexual offences against children result in a charge being laid or recommended against the accused

Overall, three in ten (30%) incidents involving online sexual offences against children between 2014 and 2022 resulted in a charge being laid or recommended against an accused. Incidents with multiple violations were almost four times more likely than incidents with a single violation to result in a charge (61% versus 16%).

Two-thirds of uncleared incidents are classified by police as having insufficient evidence to proceed

Revisions to the collection of police-reported crime statistics in January 2018 allowed for more detailed response categories to be added to the UCR (Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, 2018; Greenland & Cotter, 2018). Police services across Canada are now able to capture greater detail on the clearance status of incidents, particularly “uncleared” (unsolved) incidents. Analysis focusing on specific clearance categories will be limited to data reported between 2018 and 2022.

Between 2018 and 2022, there were 6,719 uncleared incidents of online sexual offences against children (excluding child pornography incidents). Of this number, slightly more than two-thirds (68%) were classified by police as having insufficient evidence to proceed with laying—or the recommendation of—a charge against an accused.

Section 2: Characteristics of victims of online child sexual exploitation

The increased use of technology has sparked concern over the safety of children and youth on the Internet, particularly with regard to OCSE. The Internet presents very few obstacles for offenders who want to communicate with children through virtual chatrooms and social media platforms. The lack of safeguards on the Internet, coupled with the normalization of online relationships among young people, increases a child’s vulnerability to OCSE (Kloess et al., 2019).

The short- and long-term impacts of online child sexual exploitation are well-documented. Research has consistently shown that victims of OCSE often suffer a wide range of negative outcomes, often across their lifespan, including impaired relationships, feelings of self-blame, negative sexual development, substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, and suicide (Gerke et al., 2023; Hanson, 2017; Joleby et al., 2020; Ogrodnik, 2010; Widom et al., 2006). Similar harms have been documented for victims of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) (Kloess et al., 2019). These children are re-victimized each time the material is shared or viewed, long after any contact abuse has ended (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2017; Insoll et al., 2022; Martin, 2015). According to the C3P, almost half (48%) of all CSAM reappears online after being removed (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2021).

Victimization studies show that those who experience some form of victimization during childhood are at an increased risk for repeat victimization at some point in their lives (see, for example, Widom et al., 2006).

Large majority of incidents of online sexual offences against children involve a youth victim aged 12 to 17

For this analysis, victims of online sexual offences against children are grouped into two categories: children (aged 11 years and younger) and youth (aged 12 to 17 years).

Between 2014 and 2022, the large majority (84%) of victims of police-reported online sexual offences against children were youth (Table 2). This is not surprising because youth are much more likely than children—especially young children—to have access to smartphones and the Internet, to know how to access online chat rooms, and to have their own social media accounts.

Further, most (84%) victims were girls. When looking at specific police-reported offences, girls aged 12 to 17 were disproportionately more likely than boys aged 12 to 17 to be victims of online luring (84% of all victims), non-consensual distribution of intimate images (86%), invitation to sexual touching (86%) and other sexual offences against children (79%) (Table 2).

These findings are consistent with previously published results which show that police-reported sexual offences among youth are much higher among girls compared to boys (Conroy, 2018). However, this difference could be attributed, in part, to discrepancies in reporting practices across genders. Research shows that feelings of shame, guilt and embarrassment, as well as social stereotypes of masculinity, may prevent boys and men from reporting their victimization to the police (Collin-Vézina et al., 2015; Mathews et al., 2017). One type of crime that appears to disproportionately affect boys and young men—often boys between the ages of 15 and 17—is sextortion, which involves a person threatening to disseminate sexually explicit or intimate images of someone without their consent for the purposes of obtaining additional images, sexual acts or money (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b; Patchin & Hinduja, 2020; Sutton, 2023; Wolak et al., 2018).Note

Children most often victimized by a stranger, and youth by a stranger or casual acquaintance

Overall, most victims of online sexual offences against children were victimized by a non-family member (Table 3). Almost six in ten (57%) child victims were victimized by a stranger, a proportion driven by incidents of child luring via a computer (62%). Youth were most likely to be victimized by a stranger (37%) or a casual acquaintance (27%). A stranger was most often the accused for incidents of child luring (45%) involving a youth victim, while one-third (32%) of youth victims of invitation to sexual touching were victimized by a casual acquaintance.

Among victims of online sexual offences against children, children were almost twice as likely than youth to be victimized by a family member (14% versus 8%, respectively).

Youth victims of non-consensual distribution of intimate images most often victimized by someone they know

In 2015, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act made the non-consensual distribution of intimate images (NCDII) a Criminal Code offence. Research shows that “sexting”—that is, the creation and sending of one’s own sexual images—often involves youth and has become more common with advancements in technology and increased use of smartphones among this age group (Barroso et al., 2021; Dekker et al., 2019; Gámez‐Guadix et al., 2022).

Self-producing intimate images—and consensually sharing these images with other youth—has been considered a form of sexual expression that is consistent with adolescent development and risk-taking (Barroso et al., 2021; Englander, 2019). However, forwarding or sharing these intimate images beyond their intended recipient—without consent from the original sender—is a criminal offence. The act of non-consensually sharing intimate images often has the intention to cause embarrassment, shame, humiliation, and can result in negative well-being outcomes for victims (Dekker et al., 2019; Dodge & Spencer, 2017; Zyi & Bitton, 2021). The permanency of digital images on the Internet further contributes to negative outcomes because victims feel that they have no control over who views or shares their images (Joleby et al., 2020; Martin, 2015).

There were 1,728 police-reported incidents of NCDII between 2015 to 2022, translating into an average annual rate of 3 incidents per 100,000 children and youth (Table 1). NCDII was reported as the most serious violation for almost all (98%) of these incidents.Note Of these incidents, three-quarters (76%) had a single violation, while 15% had one secondary violation related to child pornography. A small proportion (4%) of incidents had two secondary violations related to child pornography (both accessing or possessing child pornography and making or distributing child pornography).

Research suggests that this offence often involves a youth victim and a youth perpetrator (Howard et al., 2023; Gámez‐Guadix et al., 2022). Between 2015 to 2022, nearly all (97%) child victims of NCDII offences were youth (Table 3). During this period, the median age of victims was 15 years for girls and 14 years for boys. The median age of accused persons for this offence was 15 years for boys and 14 years for girls. Nine in ten (90%) persons accused of this offence were youth. Specifically, boys aged 12 to 17 accounted for two-thirds (66%) of all accused persons, while girls aged 12 to 17 accounted for just under one-quarter (23%).

One-third (33%) of youth victims said that a casual acquaintance was responsible for the distribution of their intimate images, while around one-quarter said they were victimized by a current or former dating or intimate partner (28%) or a friend (21%). A stranger was the perpetrator in 14% of such incidents. Similarly, a casual acquaintance was also the most common perpetrator in NCDII incidents involving child victims, followed by a friend and a stranger (39%, 18% and 16%, respectively).

Section 3: Characteristics of persons accused of online child sexual exploitation

While child sexual exploitation predates the Internet, advancements in digital technologies have provided novel opportunities for perpetrators to engage in sexual crimes against children (Kloess et al., 2019; Kloess & van der Bruggen, 2021). Perpetrators also have the potential to seek out and communicate with multiple victims—in different locations—at the same time (Briggs et al., 2011).

The Internet has also changed the ways that perpetrators can communicate with one another, including the creation of online communities for those who engage in the sexual exploitation and abuse of children (Kloess & van der Bruggen, 2021; Leukfeldt et al., 2017). These online communities create virtual spaces to network with others who share an interest in nonconventional—and often criminal—behaviours (Stalans & Finn, 2016). Virtual communities can also use the Internet as a platform for commercial sexual exploitation; that is, buying and selling CSAM, as well as providing buyers the option to make specific requests for the content they would like to purchase. This online marketplace creates a demand for the continued production of child pornography and, in doing so, the continued sexual exploitation of children (Drejer et al., 2023; Kloess et al., 2019; Westlake & Bouchard, 2016).

Relatively little is known about online child sexual exploitation offenders because they are often difficult to identify and prosecute (Rimer, 2019). This is an important gap to fill. Between 2014 and 2022, police services across Canada identified 13,341 individuals as accused in incidents involving online child sexual exploitation.Note

Boys and men account for the vast majority of accused

Like trends in violent crime overall, from 2014 to 2022, boys and men accounted for the majority (92%) of accused persons in incidents of online sexual offences against children (Table 5). When child pornography offences were included, they represented 91% of all accused.

Boys and men represented the vast majority of accused across all offence types, especially for incidents of invitation to sexual touching (97%), luring a child (96%) and possessing or accessing child pornography (90%).

In contrast, girls and women accounted for a much smaller proportion of accused persons (9% when including child pornography incidents). However, girls and women represented one-quarter (25%) of persons accused in incidents of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, with almost all (95%) being between the ages of 12 and 17 years.

Girls aged 12 to 17 much more likely than their older counterparts to be accused across almost all offence types

Girls between the ages of 12 to 17 years were much more likely than their older counterparts to be an accused of OCSE (Table 5). This remained true across all offence types, except for invitation to sexual touching, where most accused were aged 25 to 44 years (62% of accused girls and women). The median age of accused girls and women in OCSE incidents was 14 years.

In comparison, boys and men accused of OCSE tended to be much older, with a median age of 26 years. Specifically, the median ages of accused boys and men was 24 years for online sexual offences against children and 29 years for online child pornography.

Women more often accused with others, while men often act alone

As noted, there were 13,341 persons accused of committing an Internet-related sexual offence against children between 2014 and 2022.Note Police-reported data show that girls and women often committed an offence with at least one other person, whereas boys and men generally acted alone. Specifically, more than half (53%) of girls and women had a co-accused while the vast majority (89%) of boys and men were the only accused in incidents of OCSE. However, when looking at specific offence categories, girls and women accused of luring (55%), invitation to sexual touching (62%) and other sexual offences (56%) were more likely than not to act alone.

Rate of accused persons identified highest in the territories and Quebec

While offline (contact) crimes involve a victim and perpetrator in a specific location together, the borderless nature of online activities means that a victim of cybercrime might be victimized by a perpetrator operating in another location, even across the world. In Canada, local police services may deal with initial complaints or reports of online child sexual exploitation. However, the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC) is the Canadian body responsible for conducting investigations related to this crime and is the point of contact for international agencies reporting child sexual exploitation materials which were uploaded to the Internet in Canada. The NCECC is an extension of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and provides services and support to Canadian and international police (Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2019).

Between 2018 and 2022, there were 10,652 incidents of online child sexual offences against children where a victim was identified, and around 8,400 individuals were identified as accused.Note These numbers represented an average annual rate of 30 incidents per 100,000 children and youth, and 5 people accused per 100,000 population aged 12 and older (Table 6).

Quebec had the highest average annual rate of accused among the provinces (9 accused per 100,000 population aged 12 years and older), followed by Manitoba (7) and Nova Scotia (7). While the actual numbers were small, the territories had the highest average annual rates of accused persons identified in connection with an OCSE offence when population size was accounted for. Nunavut had the highest rate (18 accused per 100,000), followed by the Northwest Territories (15) and Yukon (14) (Table 6). These rates were around three times higher than the national average (5).

Section 4: Police-reported incidents of child pornography

There exists a perception among a small minority of people that downloading and viewing sexual images of children online should not be considered criminal because the offender has not engaged in overt sexual abuse (Rimer, 2019). However, child pornography is not a victimless crime. The harmful consequences of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) are well-documented throughout the literature. Research suggests that the long-term psychological impacts of CSAM can be as severe as contact (offline) sexual abuse (Hanson, 2017; Insoll et al., 2022; Joleby et al., 2020; Whittle et al., 2013). Previous studies have suggested that the permanence of CSAM contributes to increased trauma symptoms and higher levels of post-traumatic stress disorder in CSAM victims when compared with victims of non-digitalized child sexual abuse (Joleby et al., 2020). Victims of child pornography must live with the knowledge that their abusive experiences are being circulated online, thus continuing their victimization (Christensen et al., 2023).

C3P—a national charity dedicated to the personal safety of all children—established and operates Project Arachnid, a web platform designed to detect known images of CSAM and issue removal notices to electronic service providers (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2021). However, the amount of CSAM on the Internet that needs verifying for removal purposes far outpaces the human resources available, creating large backlogs and long delays in removing flagged content. There may also be long delays in child pornography cases where it cannot be definitively determined that the individual is under the age of 18. This is challenging because if it cannot be determined that the individual is under the age of 18, the material does not meet the Criminal Code definition of child pornography.

For readability purposes, CSAM and child pornography are used interchangeably throughout this section.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Artificial intelligence and child sexual abuse material

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) is changing the way Canadians live. By automating mundane tasks and optimizing performance, AI has the potential to make daily life easier. Generative AI software is becoming more accessible to the public and is being used more frequently in virtually all fields. For instance, AI allows marketing companies to provide customers with more personalized shopping experiences, improves efficiency and service delivery through all levels of government, and can automate administrative tasks for health care workers (De Mauro et al., 2022).

However, the use of AI also comes with risks. One of the biggest risks of AI in relation to the online safety of children and youth is AI-generated child sexual abuse material (AI CSAM) using deep learning algorithms (deepfake pornography). Deepfakes are images or recordings that have been convincingly altered or manipulated using AI software to misrepresent a person to make it appear as though they are engaging in an act. While using this software previously required a thorough understanding of deep learning algorithms and writing code, user friendly apps and open-source AI generation models make it possible for anybody to generate and distribute realistic CSAM (Harris, 2019). Many software programs are publicly available and can be downloaded to personal computers, making it very difficult to find and prosecute offenders.

Perpetrators can access public pictures from social media platforms, like Facebook and Instagram, and superimpose the face of a person onto another person’s body. AI CSAM enables offenders to generate thousands of images at a time, all while taking advantage of the anonymity that the Internet provides. This is rapidly increasing the quantity of CSAM available on the Internet.

AI-generated CSAM can have devastating impacts on victims and has been compared to the impacts experienced by victims of NCDII offences. These short- and long-term impacts include anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, social isolation, harassment or violence, and suicidal thoughts (Öhman, 2019).

The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) released a snapshot of the number of AI CSAM being generated over a one-month period in 2023. During this one-month period, more than 20,200 AI-generated images were found to have been posted to one dark web CSAM forum. Of these, more than 11,000 images were selected for assessment by IWF analysts. More than one-quarter (27%) of these images were assessed as criminal (Internet Watch Foundation, 2023).

AI CSAM is a legal grey area in some countries. Canada, however, appears to have banned any visual representation of someone who is—or is depicted as being—under the age of 18 engaging in sexual activity, regardless of whether the image or video is real or artificially created.Note

Law enforcement agencies are faced with the growing challenge of determining whether reported CSAM is real or not, potentially diverting significant resources away from children and youth immediately at risk of sexual abuse (Internet Watch Foundation, 2023). As the technology continues to evolve, improving models are making AI CSAM so realistic that CSAM analysts—who are experts in their field—are unable to distinguish between real and AI CSAM (Öhman, 2019).

End of text box 2

Rate of police-reported online child pornography has almost quadrupled since 2014

Since 2015, reporting requirements for child pornography include separate offences in the UCR for accessing or possessing child pornography and making or distributing child pornography. Combined, these offences make up all child pornography offences.Note Prior to 2015, child pornography incidents were counted simply as child pornography, regardless of the offence type.

In total, there were 45,816 police-reported incidents of online child pornography between 2014 and 2022. In 2022, there were 9,131 incidents of online child pornography, up 23% from 7,434 incidents in 2021. The rate of online child pornography almost quadrupled between 2014 (32 incidents per 100,000 children and youth) and 2022 (125 incidents per 100,000).

This article only includes child pornography offences that had an online component. However, of all child pornography incidents reported by police services between 2018 and 2022, six in ten (59%) were cyber-related.

While police-reported data show an increase in child pornography incidents, it cannot be determined how much of the increase is attributed to an actual increase in the number of incidents, or whether the increase is largely due to child pornography being reported more. For example, the increase in the number of child pornography incidents between 2020 and 2022 could be, in part, attributed to increased reporting by people who may have been inadvertently exposed to CSAM while spending more time on the Internet during the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, greater investments in the commitment towards combatting OCSE, including raising awareness and encouraging people to report through Cybertip.ca, has likely had an impact on the number of incidents reported to police.

Another factor cited by police services that may contribute to the rising rates of reported child pornography is the continued compliance with An Act respecting the mandatory reporting of Internet child pornography by persons who provide an Internet service (2011), whereby persons or entities providing an Internet service to the public are required to report known or suspected incidents of child pornography (Moreau, 2020).

Making or distributing child pornography offences account for most child pornography incidents

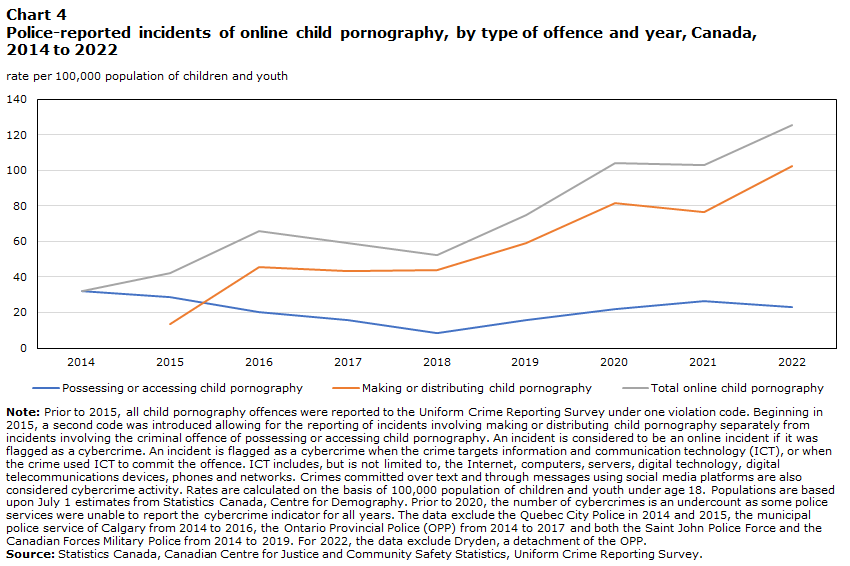

Since the introduction of the two separate offence types in 2015, making or distributing child pornography has accounted for the vast majority of total child pornography incidents each year, with the exception of the inaugural year (Chart 4). Of the 45,816 incidents of child pornography reported to police between 2014 and 2022, 32,824—or 72% of all incidents—were related to making or distributing child pornography.

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Cyber violation | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population of children and youth | |||||||||

| Possessing or accessing child pornography | 32 | 29 | 20 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 22 | 26 | 23 |

| Making or distributing child pornography | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 14 | 46 | 43 | 44 | 59 | 82 | 77 | 102 |

| Total online child pornography | 32 | 42 | 66 | 59 | 52 | 75 | 104 | 103 | 125 |

|

.. not available for a specific reference period Note: Prior to 2015, all child pornography offences were reported to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey under one violation code. Beginning in 2015, a second code was introduced allowing for the reporting of incidents involving making or distributing child pornography separately from incidents involving the criminal offence of possessing or accessing child pornography. An incident is considered to be an online incident if it was flagged as a cybercrime. An incident is flagged as a cybercrime when the crime targets information and communication technology (ICT), or when the crime used ICT to commit the offence. ICT includes, but is not limited to, the Internet, computers, servers, digital technology, digital telecommunications devices, phones and networks. Crimes committed over text and through messages using social media platforms are also considered cybercrime activity. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population of children and youth under age 18. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Prior to 2020, the number of cybercrimes is an undercount as some police services were unable to report the cybercrime indicator for all years. The data exclude the Quebec City Police in 2014 and 2015, the municipal police service of Calgary from 2014 to 2016, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) from 2014 to 2017 and both the Saint John Police Force and the Canadian Forces Military Police from 2014 to 2019. For 2022, the data exclude Dryden, a detachment of the OPP. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||||||||

Chart 4 end

Most child pornography incidents are classified by police as having insufficient evidence to proceed

Between 2018 and 2022, the vast majority (88%) of child pornography incidents reported to the UCR were not cleared (i.e., unsolved). An incident may remain uncleared for a few reasons: the incident is still under investigation or there is insufficient evidence to proceed with laying a charge against a perpetrator.Note Like incidents of online sexual offences against children, most child pornography incidents were classified as having insufficient evidence to proceed with laying or recommending a charge.

Between 2018 and 2022, three-quarters (76%) of child pornography incidents fell into this category, driven by a higher proportion of making or distributing child pornography incidents (83%) compared to possessing or accessing child pornography (52%). Some websites allow users to download content directly to their personal devices, which may make it easier for investigators to obtain evidence in relation to this offence.

Incidents of possessing or accessing child pornography most likely to result in a charge

Of the 45,816 incidents of child pornography reported to police between 2014 and 2022, 6,167 were cleared by police. In total, 3,926 of these incidents resulted in a charge being laid or recommended against an accused.

Possessing or accessing child pornography incidents were more than twice as likely as making or distributing child pornography incidents to result in a charge against an accused (15% and 6%, respectively).

Section 5: Court charges and outcomes of child sexual offences likely committed or facilitated online

The Integrated Criminal Courts Survey (ICCS) collects information on adult criminal and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences. While this article does not follow a specific police-reported incident through the Canadian criminal court system, it is important to present an overview of court outcomes for OCSE offences.

Subsections 172.1(1) (2) and 172.2(2) of the Criminal Code explicitly mention the use of telecommunications in its definitions of two offences relating to the sexual victimization of children: luring a child, and agreement or arrangement (sexual offence against a child). An analysis of court charges involving these offences are presented in this section, along with charges of other Criminal Code violations that have a higher chance of being committed or facilitated online, namely, child pornography and the NCDII (based on what is shown in police-reported data). In this section, combined, these offences are also referred to as online child sexual offences.

For detailed information on the court outcomes of police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation between 2014 and 2020 using linked data from the UCR and ICCS, see Ibrahim, 2023.

From April 2014 to March 2021, criminal courts in Canada processed 30,983 charges related to child sexual offences likely committed or facilitated online.Note These charges were processed as part of 10,515 completed cases which comprised 67,549 total charges.Note Based on the number of total charges and cases completed during this time frame, adult cases averaged 6.8 charges per case, and youth cases had an average of 4.7 charges per case. In regard to OCSE, adult cases averaged 3 charges compared with 2.5 charges per case in youth courts.

In adult criminal court, around one-third (34%) of charges laid for child sexual offences likely committed online resulted in a guilty finding. Just over six in ten (63%) charges were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged (Table 7). Slightly more charges in youth court resulted in a guilty finding (44%), with around half (51%) being stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged.

In adult criminal court, the most common charges related to OCSE were for possessing or accessing child pornography (41%), followed by making or distributing child pornography (28%)Note and luring a child (22%). Just over one-third (35%) of possessing or accessing child pornography charges resulted in a guilty finding. Most (62%) of the charges for this offence resulted in the charge being stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged.

More than one-third (37%) of charges in youth court were related to making or distributing child pornography and a further 28% were possessing or accessing child pornography (Table 7).

Probation most likely sentence for youth, custody for adults

In adult criminal courts, more than three-quarters (78%) of guilty cases involving child sexual offences likely committed online led to a custodial sentence (Table 7). Around one in ten (9%) guilty cases resulted in probation. The exception to this was for adults found guilty of non-consensual distribution of intimate images where the most common sentence was probation (42%).

Meanwhile, in youth courts, youth found guilty of committing an online child sexual offence were most likely to be sentenced to probation (62%). The Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA) aims to divert youth who have been accused of a crime away from the formal justice system by applying extrajudicial measuresNote whenever possible before deciding to charge a young person. The YCJA applies to youth who are alleged to have committed a criminal offence and are at least 12 but under 18 years old (Youth Criminal Justice Act, 2002).

Summary

Online child sexual exploitation encompasses a wide range of Criminal Code offences, including online sexual offences against children and child pornography offences.

Between 2014 and 2022, there were 15,630 police-reported incidents of online sexual offences against children (where the victim had been identified by police) and 45,816 incidents of online child pornography (where the victim had not been identified). In 2022, the rate of online child sexual exploitation (OCSE)—which is comprised of both online sexual offences against children and online child pornography—reached its highest since cybercrime data first became available in 2014. In 2022, there were 160 incidents per 100,000 children and youth, which was largely driven by the rate of child pornography (125 incidents per 100,000 children and youth). The increase over this period may be partly attributed to an uptake in the use of the cybercrime flag (which was newly introduced to all police services in Canada in 2014) and more funding being allocated to police services to combat OCSE. These increases, however, are supported by reports from external data sources, specifically data from Cybertip.ca, Canada’s national tipline for the reporting of child exploitation on the Internet.

There are a number of challenges that make investigating and solving Internet-related crimes difficult. The Internet is borderless; most victims and offenders are not located in the same place. This, coupled with online protections used by offenders to guarantee anonymity, make it difficult to locate, track down, and prosecute those who commit cybercrime-related offences. Between 2014 and 2022, six in ten (59%) police-reported incidents related to online sexual offences against children were not cleared. An incident was more likely to be cleared when it contained multiple violations.

Between April 2014 and March 2021, criminal courts in Canada processed 30,983 charges related to child sexual offences likely committed or facilitated online. In adult criminal court, the most common charges related to OCSE were for possessing or accessing child pornography, making or distributing child pornography, and luring a child.

Limitations and considerations

This analysis has several limitations:

- Police-reported data is particularly susceptible to underreporting and underestimation, especially when the incident involves a child. Due to their age, children may not recognize online sexual abuse or, if they do, often rely on adults to report the incident to the police. As such, police-reported online child sexual exploitation incidents represent a fraction of all such incidents in Canada.

- Online child sexual exploitation is a borderless crime; in other words, a perpetrator can be anywhere in the world and victimize a Canadian child or youth or, conversely, a Canadian perpetrator may target victims outside of Canada. Transnational child sex offenders are hard to prosecute, with Canadian police often relying on international cooperation to locate and track down perpetrators.

- Technological advancements continue to increase anonymity capabilities, making it difficult for police services to locate and track down perpetrators.

- The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey does not distinguish between accessing and possessing child pornography. As such, it is not possible to determine whether incidents involved the live streaming of child sexual abuse material versus downloading and physically possessing it.

- As noted, police services can report up to four violations per incident to the UCR. However, reporting secondary violations is not mandatory, which can impact the analysis of secondary violations.

- Many police departments across Canada do not have the resources to investigate cybercrime incidents. These incidents are often sent to police departments with the capacity to investigate them, impacting the quality of the “location” variable.

Detailed data tables

Data sources

Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey was established in 1962 with the co-operation and assistance of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police. The UCR was designed to measure criminal incidents that have been reported to federal, provincial/territorial and municipal police services in Canada. One incident can involve multiple offences. Counts presented in this article are based on the most serious cyber offence in the incident as determined by a standard classification rule used by all police services. The cyber violation may not be the most serious violation in the incident.

Each year, the UCR database is “frozen” at the end of May for the production of crime statistics for the preceding calendar year. However, police services continue to send updated data to Statistics Canada after this date for incidents that occurred in previous years. Generally, these revisions constitute new accused records, as incidents are solved and accused persons are identified by police. Some new incidents, however, may be added and previously reported incidents may be deleted as new information becomes known. Revisions are accepted for a one-year period after the data are initially released. The data are revised only once and are then permanently frozen.

Integrated Criminal Courts Survey

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) collects statistical information on adult and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences.

All adult courts have reported to the adult component of the survey since the 2006/2007 fiscal year. Information from superior courts in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan as well as municipal courts in Quebec was not available for extraction from their electronic reporting systems and was therefore not reported to the survey. Superior court information for Prince Edward Island was unavailable until 2018/2019.

A completed charge refers to a formal accusation against an accused person or company involving a federal statute offence that was processed by the courts at the same time and received a final decision. A case is defined as one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts and received a final decision. A case combines all charges against the same person having one or more key overlapping dates (date of offence, date of initiation, date of first appearance, date of decision, or date of sentencing) into a single case.

References

Aguerri, J., Molnar, L., and Miró‑Llinares, F. (2023). Old crimes reported in new bottles: the disclosure of child sexual abuse on Twitter through the case #MeTooInceste. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(27).

Alaggia, R., Collin-Vézina, D., and Lateef, R. (2019). Facilitators and barriers to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) disclosures: a research update (2000-2016). Trauma, violence & abuse, 20(2), 260-283.

Barroso, R., Ramião, E., Figueiredo, P. and Araújo, A.M. (2021). Abusive sexting in adolescence: Prevalence and characteristics of abusers and victims. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-9.

Briggs, P., Simon, W.T. and Simonsen, S. (2011). An exploratory study of Internet-initiated sexual offences and the chat room sex offender: has the Internet enabled a new typology of sex offender? Sexual Abuse, 23(1), 72-91.

Burczycka, M. and Conroy, S. (2017). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2022). Online harms: Sextortion.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2021). Project Arachnid: Online availability of child sexual abuse material. https://protectchildren.ca/pdfs/C3P_ProjectArachnidReport_Summary_en.pdf

Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. (2018). Revising the collection of founded and unfounded criminal incidents in the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. Juristat Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Chandran, S., Bhargava, S., and Kishor, M. (2019). Under reporting of child sexual abuse-The barriers guarding the silence. Telangana Journal of Psychiatry, 4(2), 57-60.

Christensen, L.S. and Vickery, N. (2023). The characteristics of virtual child sexual abuse material offenders and the harms of offending: A qualitative content analysis of print media. Sexuality & Culture, 27, 1813-1827.

Collin-Vézina, D., De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M., Palmer, A.M. and Milne, L. (2015). A preliminary mapping of individual, rational, and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 123-134.

Conroy, S. (2018). Police-reported violence against girls and young women in Canada, 2017. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. (2021). Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. and Savage, L. (2019). Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Dekker, A., Wenzlaff, F., Daubmann, A., Pinnschmidt, H.O. and Briken, P. (2019). (Don’t) look at me! How the assumed consensual or non-consensual distribution affects perception and evaluation of sexting images. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8, 706.

De Mauro, A., Sestino, A. and Bacconi, A. (2022). Machine learning and artificial intelligence use in marketing: a general taxonomy. Italian Journal of Marketing, 439-457.

Dodge, A. and Spencer, D.C. (2017). Online sexual violence, child pornography or something else entirely? Police responses to non-consensual intimate image sharing among youth. Social and Legal Studies, 27(5), 1-22.

Drejer, C., Riegler, M.A., Halvorsen, P., Johnson, M.S., and Baugerud, G.A. (2023). Livestreaming Technology and Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: A Scoping Review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 1-15.

Englander, E. (2019). What do we know about sexting, and when did we know it? Journal of Adolescent Health, 65, 577-578.

EPCAT International (2018), “Trends in online child sexual abuse material”. Bangkok: ECPAT International.

Frenette, M., Frank, K., and Deng, Z. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: School Closures and the Online Preparedness of Children. STATCAN COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001.

Gámez‐Guadix, M., Mateos‐Pérez, E., Wachs, S., Wright, M., Martínez, J. and Íncera, D. (2022). Assessing image-based sexual abuse: Measurement, prevalence, and temporal stability of sextortion and nonconsensual sexting (“revenge porn”) among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 94(5), 789-799.

Gerke, J., Gfrorer, T., Mattstedt, F.K., Hoffmann, U., Fegert, J.M., and Rassenhofer, M. (2023). Long-term mental health consequences of female-versus-male perpetrated child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 143.

Greenland, J. and Cotter, A. (2018). Unfounded criminal incidents in Canada, 2017. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Hanson, E. (2017). “The impact of online sexual abuse on children and young people.” Online risk to children: Impact, Protection and Prevention, 97-122.

Harper, C.A., Smith, L., Leach, J., Daruwala, N.A., and Fido, D. (2023). Development and validation of the beliefs about revenge pornography questionnaire. Sexual Abuse, 35(6), 748-783.

Harris, D. (2019). Deepfakes: false pornography is here and the law cannot protect you. Duke Law & Technology Review, 17(1).

Henry, N. and Powell, A. (2015). Beyond the ‘sext’: Technology-facilitated sexual violence and harassment against adult women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 48(1), 104-118.

Howard, D., Jarman, H.K., Clancy, E.M., Renner, H.M., Smith, R., Rowland, B., Toumbourou, J.W., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz. M. and Klettke, B. (2023). Sexting among Australian adolescents: Risk and protective factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52, 2113-2130.

Ibrahim, D. (2023). Online child sexual exploitation and abuse: Criminal justice pathways of police-reported incidents in Canada, 2014 to 2020. Juristat Bulletin—Quick Fact. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-005-X.

Ibrahim, D. (2022). Online child sexual exploitation and abuse in Canada: A statistical profile of police-reported incidents and court charges, 2014 to 2020. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Insoll, T., Ovaska, A.K., Nurmi, J., Aaltonen, M. and Vaaranen-Valkonen, N. (2022). Risk factors for child sexual abuse material users contacting children online: Results of an anonymous multilingual survey on the dark web. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(2).

Internet Watch Foundation. (2023). “How AI is being abused to create child sexual abuse imagery.” Accessed on November 6, 2023.

Joleby, M., Lunde, C., Landström, S. and Jonsson, L.S. (2020). ’All of me is completely different’: Experiences and consequences among victims of technology-assisted child sexual abuse. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 606218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606218.

Kloess, J.A., J. Woodhams, H. Whittle, T. Grant., and Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.E. (2019). The challenges of identifying and classifying child sexual abuse material. Sexual Abuse, 31(2), 173-196.

Kloess, J.A. and van der Bruggen, M. (2021). Trust and relationship development among users in dark web child sexual exploitation and abuse networks: A literature review from a psychological and criminological perspective. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 24(3), 1220-1237.

Leukfeldt, E.R., Kleemans, E.R., and Stol, W.P. (2017). Cybercriminal networks, social ties and online forums. British Journal of Criminology, 57, 704-722.

Martin, J. (2015). Conceptualizing the harms done to children in sexual abuse images online. Child & Youth Services, 36(4), 267-287.

Mathews, B., Bromfield, L., Walsh, K., Cheng, Q. and Norman, R.E. (2017). Reports of child sexual abuse of boys and girls: Longitudinal trends over a 20-year period in Victoria, Australia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 66, 9-22.

Moreau, G. (2022). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Moreau, G. (2021). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2020. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Ogrodnik, L. (2010). Child and youth victims of police-reported violent crime, 2008. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Profile Series. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85F0033M, no. 23.

Öhman, C. (2019). Introducing the pervert’s dilemma: a contribution to the critique of Deepfake Pornography. Ethics and Information Technology, 22, 133-140.

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2020). Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a national survey of U.S. youth. Sexual abuse, 32(1), 30-54.

Reich, S. M., Subrahmanyam, K. and Espinoza, G. (2012). Friending, IM’ing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 356-368.

Rimer, J.R. (2019). ‘In the street they’re real, in a picture they’re not’: Constructions of children and childhood among users of online sexual exploitation material. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90, 160-173.

Rotenberg, C. (2017). Police-reported sexual assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014: A statistical profile. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. (2019). “Actions to combat online child sexual exploitation.” Accessed on November 6, 2023.

Ryngaert, C. (2023). Extraterritorial enforcement jurisdiction in cyberspace: normative shifts. German Law Journal, 24, 537-550.

Seto, M.C. (2013). Internet sex offenders. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Stalans, L.J. and Finn, M.A. (2016). Understanding how the Internet facilitates crime and deviance. Victims & Offenders, 11(4), 501-508.

Sutton, D. (2023). Victimization of men and boys in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Taylor, S.C. and Gassner, L. (2010). Stemming the flow: Challenges for policing adult sexual assault with regard to attrition rates and under-reporting of sexual offences. Police Practice and Research, 11(3), 240-255.

Twenge, J.M. (2019). More time on technology, less happiness? Associations between digital-media use and psychological well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(4), 372-379.

Verduyn, P. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274-302.

Westlake, B.G. and Bouchard, M. (2016). Liking and hyperlinking: Community detection in online child sexual exploitation networks. Social Science Research, 59, 23-36.

Whittle, H.C., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. and Beech, A.R. (2013). Victims’ voices: the impact of online grooming and sexual abuse. Universal Journal of Psychology, 1(2), 59-71.

Widom, C.S., Czaja, S.J., and Dutton, M.A. (2006). Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 785-796.

Wolak, J., Finkelhor, D., Walsh, W., and Treitman, L. (2018). Sextortion of minors: Characteristics and dynamics. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 72-79.

Woodhams, J., Kloess, J.A., Jose, B., and Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.E. (2021). Characteristics and behaviours of anonymous users of dark web platforms suspected of child sexual offences. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

Youth Criminal Justice Act. YCJA 2002. Parliament of Canada.

Zvi, L. and Bitton, M.S. (2021). Perceptions of victim and offender culpability in non-consensual distribution of intimate images. Psychology, Crime & Law, 27(5), 427-442.

- Date modified: