Trafficking in persons in Canada, 2020

by Shana Conroy and Danielle Sutton, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- Police services in Canada reported 2,977 incidents of human trafficking—that is, recruiting, transporting, transferring, holding, concealing and exercising control over a person for the purposes of exploitation—between 2010 and 2020.

- During this time, nearly nine in ten (86%) incidents of human trafficking were reported in census metropolitan areas, compared with around six in ten (58%) violent incidents overall.

- More than half (57%) of the incidents involved human trafficking offences alone while 43% involved at least one other type of violation, most often related to the sex trade.

- The vast majority (96%) of detected victims of human trafficking were women and girls. In all, one in four (25%) victims were under the age of 18. Meanwhile, one in five (20%) were aged 25 to 34.

- Just over half (52%) of all human trafficking incidents had no accused person identified in connection with the incident.

- The large majority (81%) of persons accused of human trafficking were men and boys. Most commonly, accused persons were aged 18 to 24 (41%), followed by those aged 25 to 34 (36%).

- Based on results from a record linkage, there were 1,793 unique persons accused of police-reported human trafficking between 2009 and 2020. Three-quarters (75%) of these accused had previously been implicated in other criminal activity. Following an initial contact with police for human trafficking, one in nine (11%) accused were implicated in a separate incident of human trafficking during the reference period.

- Between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, there were 834 cases completed in adult criminal courts that involved at least one charge of human trafficking.

- Human trafficking cases took almost twice as long to complete than violent adult criminal court cases. The median amount of time it took to complete an adult criminal court case involving at least one violent charge was 176 days. In contrast, it took a median of 373 days to complete a case involving at least one human trafficking charge.

- As the most serious decision in adult criminal court, a finding of guilt was less common for cases involving human trafficking (12%) than for those involving sex trade charges (33%) or violent charges (48%).

Trafficking in persons, also known as human trafficking, is often described as a modern-day form of slavery that is thought to affect every country worldwide, either as a point of origin or destination (Ross et al. 2015; UNODC 2021a). Human trafficking involves the recruitment, transportation, harbouring or exercising control, direction or influence over the movements of a person for the purposes of exploitation (Public Safety Canada 2020a; Public Safety Canada 2019; UNODC 2021a). Taking into consideration the illicit nature of human trafficking, data compiled by the International Labour Organization estimate that, in 2016, just under 20 million persons worldwide were victims of trafficking either through forced labour or sexual exploitation (International Labour Organization 2017). Canadian data reveal that the number of police-reported incidents have been increasing since 2009 (Cotter 2020; Ibrahim 2021; Parliament of Canada 2018), of which the vast majority of investigations were related to some form of sexual exploitation (Department of Justice 2015; UNODC 2021a).

Whether this increase is due to a rise in the number of incidents, improved detection or increased public awareness cannot be determined through official data. Data on trafficking for forced labour is limited and, as such, it is not possible to measure the extent of this form of human trafficking, in Canada or abroad. Research to date, however, has shown how gender and age of forced labour trafficking victims varies across geography and economic sector, thereby affecting different genders in unique ways (UNODC 2021a). Conversely, human trafficking for sexual exploitation is highly gendered and affects women and girls disproportionately, although men and boys can also be victims (Parliament of Canada 2018; Public Safety Canada 2019; UNODC 2021a). The risk is heightened among particular groups such as Indigenous women and girls, vulnerable youth or those with prior involvement with the child welfare system, LGBTQ2+ persons,Note migrants and others who experience social or economic marginalization (Baird et al. 2020; Parliament of Canada 2018; Public Safety Canada 2020a; Public Safety Canada 2019; UNODC 2021a).

Human trafficking is not to be confused with human smuggling, notwithstanding a major overlap between the two. The latter is, by definition, a transnational crime that often involves persons paying to be illegally transported across international borders with the promise of freedom upon arrival at the country of destination (Department of Justice 2015; Public Safety Canada 2020a). In contrast, human trafficking can also occur within a country’s borders, where victims are subjected to coercive practices and exploited in the sex trade or for forced labour (Department of Justice 2015; Public Safety Canada 2020a). That said, those who are smuggled across borders may be coerced and exploited, making them victims of human trafficking upon arrival in destination countries.

Canada has legislated provisions to combat human trafficking both domestically and transnationally, as stipulated in the Criminal Code and Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA; see Text box 1). The Criminal Code prohibits all forms of human trafficking. Further, in 2019, the Government of Canada announced a five-year National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (Public Safety Canada 2019).Note Accordingly, efforts to identify, protect and empower human trafficking victims while holding perpetrators accountable remain an ongoing governmental priority.

This Juristat article uses data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey to examine trends in human trafficking incidents that were reported to police, and discusses victim and accused person characteristics. In addition, this article will highlight prior contact with police among those accused of human trafficking. Data from the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) are also presented to examine outcomes of cases related to human trafficking in court.

This article was produced with funding support from Public Safety Canada.

Challenges with measuring human trafficking

Human trafficking victims are often isolated and hidden from the public (Farrell et al. 2019; Farrell et al. 2010; Public Safety Canada 2020a; Public Safety Canada 2019). Some healthcare workers report a lack of training in identifying and assisting individuals in potential trafficking situations (Ross et al. 2015) and victims may be unwilling or unable to report for various reasons. They may, for example, have a general distrust of authorities, be fearful or ashamed, lack knowledge of their rights in Canada, experience language barriers or have a desire to protect their traffickerNote (Casassa et al. 2021; Department of Justice 2015; Farrell et al. 2019; Farrell et al. 2010; Parliament of Canada 2018; Public Safety Canada 2019; Ward and Fouladvand 2018).

The ability of police services to detect human trafficking cases will vary by the amount of resources, training and specialized units available. The more resources and training available, the better equipped police services will be to properly categorize cases of human trafficking, interview and assist victims, and recommend or lay appropriate charges against accused persons (Farrell et al. 2019; Farrell et al. 2014; Farrell et al. 2010). Without victim testimony, however, many police services may struggle to proactively identify human trafficking cases, resulting in an underreporting of the crime.

Even when human trafficking cases are identified and charges are laid, additional challenges arise during prosecution. Successful prosecution often depends on victim testimony and corroborating evidence. Human trafficking victims, however, may be seen as less credible due to factors related to vulnerability (e.g., substance use, homelessness, mental health issues), their often coerced involvement in crimes and issues with consistency in recall due to trauma (Farrell et al. 2019; Farrell et al. 2014; Farrell et al. 2010; Ward and Fouladvand 2018). In addition to credibility concerns, victims may disappear before trial or recant their initial testimony resulting in a substantial number of human trafficking charges being stayed or withdrawn by prosecutors (Farrell et al. 2014; Millar et al. 2017; Parliament of Canada 2018).

Data collected by the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline provides the opportunity to supplement official data, improving estimates of the nature and scope of human trafficking in Canada (see Text box 3).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Human trafficking in the Criminal Code and the Immigration and Refugee

Protection Act

In 2005, the following human trafficking offences were added to the Criminal Code:

- Section 279.01: trafficking in persons

- Section 279.02: receiving financial or other material benefit for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking in persons

- Section 279.03: withholding or destroying identity documents (e.g., a passport, whether authentic or forged) for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking of that person

- Section 279.04: defines exploitation for the purpose of human trafficking offences.

In 2008/2009, the first case involving a human trafficking charge using this new legislation was completed in adult criminal court.

In 2010, section 279.011 was added to the Criminal Code which imposed mandatory minimum penalties for individuals accused of the trafficking of persons under the age of 18 years.

In 2012, the Criminal Code was amended to allow for the prosecution of Canadians and permanent residents for human trafficking offences committed internationally and to provide judges with an interpretive tool to assist in determining whether exploitation occurred (subsection 279.04(2)).

In 2014, mandatory minimum penalties were imposed on the main trafficking offence (section 279.01), as well as for receiving a material benefit from the trafficking of children (subsection 279.02(2)) and withholding or destroying documents to facilitate the trafficking of children (279.03(2)).

Section 118 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), introduced in 2002, criminalizes the cross-border trafficking of one or more persons by means of abduction, fraud, deception, threatened or actual use of force or coercion (Public Safety Canada 2019). While human trafficking differs from human smuggling, the IRPA also prohibits the smuggling of persons into Canada.

End of text box 1

Section 1: Police-reported human trafficking

Using police-reported data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey, this section presents trends in human trafficking in Canada. In this section, data from 2010 to 2020 are often combined to better examine trends and characteristics of human trafficking in Canada. Following an analysis of high-level national and regional trends, the characteristics of human trafficking incidents, victims and accused persons are discussed.

Police-reported human trafficking declined slightly in 2020

Between 2010 and 2020, there were 2,977 incidents of human trafficking reported by police services in Canada.Note This represented an average annual rate of 0.7 incidents per 100,000 population. Incidents of human trafficking accounted for 0.01% of all police-reported incidents during this time.

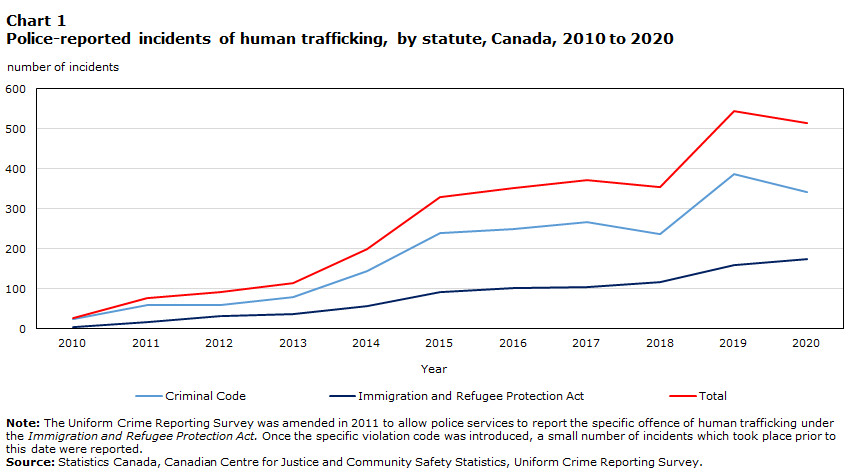

In terms of year-over-year figures, police-reported human trafficking decreased slightly in 2020 compared with 2019, from 546 to 515 incidents, or 1.5 to 1.4 incidents per 100,000 population (Chart 1). Incidents of human trafficking had increased steadily from 2010 to 2017, decreased in 2018 and peaked in 2019. The general increase in human trafficking over this time period may reflect an increase in the actual occurrence of this type of crime, but it could also be the result of enhanced efforts by police to detect, investigate and lay or recommend human trafficking charges.Note Further, the small decline in 2020 may be the result of the unique and challenging circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, wherein this type of crime might have been less likely to occur and also more likely to go undetected when it did occur. For example, with widespread lockdown measures and restrictions, not only would there have been fewer venues open to facilitate human trafficking (e.g., bars, adult clubs, massage parlours) but potential victims would have been easier to hold without detection while their friends and family, and service providers, would have had fewer opportunities to detect and report trafficking suspicions (UNODC 2021b; see Text box 2).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Year | Criminal Code | Immigration and Refugee Protection Act | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of incidents | |||

| 2010 | 23 | 3 | 26 |

| 2011 | 60 | 16 | 76 |

| 2012 | 60 | 32 | 92 |

| 2013 | 78 | 37 | 115 |

| 2014 | 143 | 57 | 200 |

| 2015 | 239 | 91 | 330 |

| 2016 | 249 | 102 | 351 |

| 2017 | 268 | 103 | 371 |

| 2018 | 238 | 117 | 355 |

| 2019 | 387 | 159 | 546 |

| 2020 | 342 | 173 | 515 |

|

Note: The Uniform Crime Reporting Survey was amended in 2011 to allow police services to report the specific offence of human trafficking under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. Once the specific violation code was introduced, a small number of incidents which took place prior to this date were reported. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 1 end

Police-reported incidents of human trafficking include Criminal Code and IRPA offences. Between 2010 and 2020, Criminal Code offences represented 70% of all human trafficking incidents while IRPA offences represented 30%, meaning three in ten incidents involved an international border crossing. While both types of human trafficking offences increased in general over the same time period, Criminal Code offences declined between 2019 and 2020 specifically.Note

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Human trafficking during the COVID-19 pandemic

The temporary layoffs across regions and industries brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic caused concern that the potential number of human trafficking victims would increase due to spikes in unemployment (UNODC 2021a). While some anecdotal evidence suggests that human trafficking has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (CCTEHT 2021b), the ability of service providers to support victims has been impacted negatively due to restrictions brought on by the pandemic.

In April 2020, the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking administered a survey to its service providers to ascertain how the pandemic has impacted their service delivery to victims (CCTEHT 2021b). Service providers continued to accept referrals but with reduced hours, remote communication and a primary focus on managing crisis cases. Shelters, with the implementation of new health and safety policies, made significant modifications to their housing rules and bed capacity (Ibrahim 2022; Women’s Shelters Canada 2020). In-person counseling services were prohibited, impacting victims of human trafficking negatively. Accessing counseling services now required a working computer, Internet access and privacy—requirements that may not be available to those most in need.

Similar observations were documented after surveying residential facilities for victims of abuse. Specifically, almost eight in ten (77%) facilities reported that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their ability to serve victims to a moderate or great extent (Ibrahim 2022). The most frequently reported challenges were related to accommodation capacity, providing services to victims and staffing issues. In response, most facilities used new technologies to communicate with victims, adapted or added new services, designated self-isolation areas and required some staff and volunteers to work from home (Ibrahim 2022). Many facilities saw an increase in crisis calls but a decrease in demand for shelter admissions, which may have reduced the ability of service providers to detect and report cases of human trafficking.

According to police-reported data from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, there was a 3% year-over-year decline in the number of incidents involving a human trafficking violation between 2019 and 2020. The largest declines were noted in October (-33%), April (-19%) and November (-15%) 2020, compared with the same months the year prior. These declines coincide with Canada entering the first and second waves of the pandemic and, in several provinces and territories, their corresponding lockdown measures. As such, during these months, potential victims were more likely to be separated from persons who could report suspicions of trafficking to the authorities. At the same time, because many individuals were living in isolation and spending increased time online, human trafficking may have increased due to online recruitment and grooming strategies but the ability to detect such increases were hindered due to the pandemic.

End of text box 2

Nova Scotia and Ontario report higher rates of human trafficking than the national average

Similar to previous human trafficking trends in Canada (Cotter 2020; Ibrahim 2021), between 2010 and 2020, the highest average annual rates of human trafficking in the provinces were documented in Nova Scotia and Ontario (Table 1).Note While Ontario and Nova Scotia represented 39% and 3% of the Canadian population in 2020 (Statistics Canada 2022), between 2010 and 2020 they accounted for 65% and 7% of police-reported human trafficking incidents, respectively. This pattern was observed in 2020 specifically when Nova Scotia reported 6.2 incidents and Ontario 2.3 incidents per 100,000 population, both above the national average (1.4 incidents).

While the figures documented in Ontario may be expected considering it is Canada’s most populous province and home to the busiest international border crossings,Note the rate of human trafficking in Nova Scotia is better explained by geographic location. Nova Scotia in general, and Halifax in particular, has been identified as a trafficking hub frequently used to move victims from Atlantic Canada to the rest of Canada (Barrett 2013; Cotter 2020). Since 2010, almost half (45%) of all human trafficking incidents in Nova Scotia were IRPA-related, the highest proportion of any province or territory.

Large majority of human trafficking incidents reported by police in urban centres

Since 2010, the large majority (86%) of human trafficking incidents have been reported by police services in census metropolitan areas (CMAs),Note and this was consistent in 2020 (82%) (Table 2). In comparison, around six in ten (58%) violent incidents were reported in CMAs overall. Between 2010 and 2020, just under half (48%) of all police-reported incidents of human trafficking were reported in five CMAs: TorontoNote (610 incidents, accounting for 20% of all incidents in Canada), OttawaNote (305, or 10% of all incidents), Montréal (220, or 7% of all incidents), Halifax (175, or 6% of all incidents) and HamiltonNote (108, or 4% of all incidents).

During the same time period (2010 to 2020), rates of human trafficking were highest in Halifax (3.7 incidents per 100,000 population), followed by Thunder Bay (3.0), Ottawa (2.7), Peterborough (2.6) and Windsor (2.3).

Compared with the average annual rates for 2010 to 2020, several CMAs had a rate of human trafficking that was notably higher in 2020 specifically: Thunder Bay (15.9 incidents per 100,000 population), Peterborough (14.7), Halifax (8.5), St. Catharines–Niagara (6.4), Saskatoon (4.7), Barrie (4.6) and Windsor (4.2). Sharp increases in rates may be attributed to increased funding to develop or expand human trafficking units; improved familiarity with investigating human trafficking cases and laying or recommending human trafficking charges; or a combination of the two.

Aligned with the patterns documented above, human trafficking in Canada is thought to take place primarily, though not exclusively, in urban centres (CCTEHT 2021a). Victims are often moved by their traffickers to avoid detection. Further, doing so contributes to psychological control as victims are often confused, isolated and dependent on those who are trafficking them (CCTEHT 2021a).

When multiple types of violations are involved in human trafficking incidents, most are related to the sex trade

Of all police-reported incidents of human trafficking during 2010 to 2020, the vast majority (95%) had a human trafficking offence listed as the most serious offence, either under the Criminal Code or IRPA.Note

More than half (57%) of human trafficking incidents involved human trafficking offences alone while 43% involved at least one other type of violation.Note When there was an associated offence, it was most often related to the sex trade.Note More specifically, since 2010, over half (58%) of human trafficking incidents with multiple violations involved an offence related to the sex trade. An offence related to physical assault was the next most common (36%), followed by a sexual assault or other sexual offence (25%) and an offence related to the deprivation of freedom (12%).Note

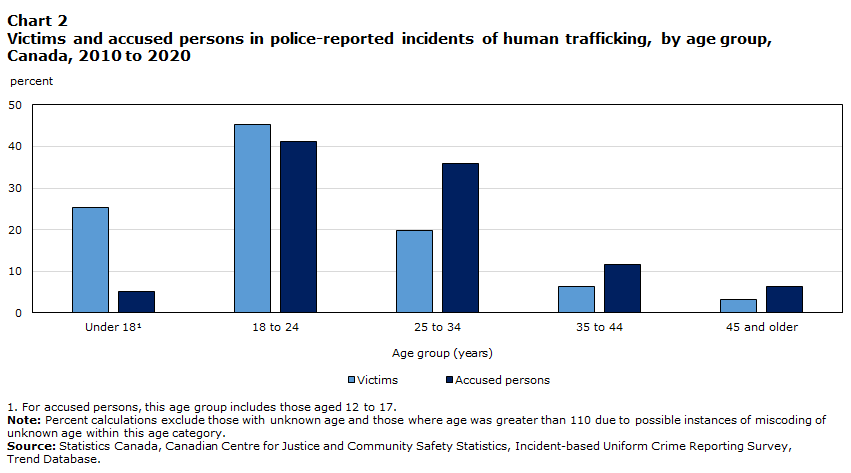

Vast majority of detected human trafficking victims are women and girls, one in four victims are younger than 18

Between 2010 and 2020, there were 2,278 victims of police-reported human trafficking in Canada. Women and girls represented the vast majority (96%) of detected victims, while men and boys accounted for a relatively small proportion (4%) of victims.Note Nearly half (45%) of all victims of human trafficking during this time were aged 18 to 24 (Chart 2).Note One in four (25%) victims were under the age of 18, while one in five (20%) were aged 25 to 34. The remaining victims were aged 35 to 44 (6%) or 45 and older (3%). In all, seven in ten (69%) victims of human trafficking were girls and young women aged 24 and younger.Note

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Age group (years) | Victims | Accused persons |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Under 18Data table for chart 2 Note 1 | 25 | 5 |

| 18 to 24 | 45 | 41 |

| 25 to 34 | 20 | 36 |

| 35 to 44 | 6 | 12 |

| 45 and older | 3 | 6 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. |

||

Chart 2 end

Studies have shown that traffickers target groups of women and girls who are at particular risk due to factors related to poverty, isolation, precarious housing, substance use, history of violence, childhood maltreatment and mental health issues (Baird et al. 2020; Parliament of Canada 2018). During the recruitment phase, traffickers regularly exploit these vulnerabilities through deception and manipulation, providing victims with the affection, care and security they may otherwise lack (UNODC 2021a). The level of violence and coercion often increase over time, resulting in lasting psychological harm for trafficking victims (Altun et al. 2017; UNODC 2021a). While police-reported data do not capture the emotional or psychological trauma, they do collect information about physical injury. Where information about injury was known, three in ten (29%) victims were injured. Of these victims, most (88%) sustained minor physical injury while major injury was less common (12%).Note

Nearly half of persons accused of human trafficking under age 25

While most detected victims of human trafficking were women and girls, between 2010 and 2020, the large majority (81%) of the 2,091 persons accused of this type of crime were men and boys.Note Most commonly, accused persons were aged 18 to 24 (41%), followed by those aged 25 to 34 (36%). Smaller proportions of accused persons were aged 35 to 44 (12%), 45 and older (6%) or youth aged 12 to 17 (5%). Overall, nearly two-thirds (65%) of those accused of human trafficking were men aged 18 to 34.

Between 2010 and 2020, among accused persons, gender differences emerged by age group. While men represented the large majority of adult accused persons—regardless of age group—the majority (56%) of youth accused were girls.Note The limited research on female traffickers in general, and female youth in particular, highlights girls’ roles in recruitment. Female youth are perceived as better positioned to appear trustworthy and are thus tasked with luring other girls (Broad 2015; Kiensat et al. 2014). Of note, the boundaries between female trafficking victims and offenders are becoming increasingly blurred (UNODC 2020). As such, it may be that a high proportion of female youth accused of trafficking were, or continue to be, themselves a victim of human trafficking. In these instances, they are often pressured to recruit others, or provide transportation, and are not personally profiting from their actions (Broad 2015).

Nearly one-third of victims experience trafficking by an intimate partner

Among victims of police-reported human trafficking, between 2010 and 2020, one in ten (9%) did not know the accused person involved in the incident—that is, they were trafficked by a stranger—while the vast majority (91%) of victims knew their trafficker. Consistent with previous research (Cotter 2020; Ibrahim 2021), nearly one-third (31%) of victims were trafficked by a current or former intimate partner. It is important to note that a tactic employed by some traffickers is to target individuals and engage them in romantic relationships, with the end goal to traffic them (UNODC 2021a).

For one-quarter (25%) of victims, the accused person was a casual acquaintance, followed by someone with whom the victim had a criminal relationshipNote (14%) or a business relationship (12%), and friends (6%).

An accused person identified in just under half of human trafficking incidents, charges laid against the vast majority of those accused

Of all incidents of human trafficking reported by police between 2010 and 2020, just over half (52%) have not been cleared, meaning an accused person has not been identified by police.Note Given that a notable proportion of victims of human trafficking were trafficked by an intimate partner, it is possible that victims did not want to identify the accused due to their shared bond or their reliance on the accused to have their basic needs met (Luz 2020). Other reasons why victims may not want to incriminate their accused include safety concerns, fear of prosecution for crimes they were pressured to commit, the emotional burden of the prosecution process or the shame and stigma associated with reporting (Department of Justice 2015; Luz 2020).

Charges were laid or recommended against an accused person for 44% of incidents during this time period, while for the remaining 4% of incidents, an accused person was identified but the incident was cleared in another way. This could include, for example, the victim requesting that no further action be taken, the incident being cleared by another agency,Note or charges not being laid or recommended due to departmental discretion or reasons beyond the control of the department.

For the vast majority (91%) of those accused of human trafficking, charges were laid or recommended. This was similar among men and women (91% versus 92%) and slightly higher among adults than youth (91% versus 88%) accused of this crime.

Human trafficking incidents more often result in charges for Criminal Code violations than Immigration and Refugee Protection Act offences

Between 2010 and 2020, there were notable differences in clearance rates among police-reported incidents of human trafficking: the majority (57%) of incidents involving Criminal Code violations were cleared by the laying or recommendation of charges, whereas this was less common for incidents involving IRPA violations (21%). Meanwhile, similar proportions were cleared by other meansNote (4% and 5%, respectively).

Human trafficking incidents with IRPA offences also less commonly resulted in charges. Among those accused of human trafficking since 2010, charges were laid or recommended against 82% of those accused in IRPA-related incidents, compared with 92% of those accused in Criminal Code-related incidents.

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

The Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline

The Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline, operated by the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking, was established in May 2019 to provide localized support to anyone impacted by trafficking. The confidential and multilingual Hotline uses a victim-centred and trauma-informed approach to share information with callers, assist with safety planning, report tips to law enforcement under certain circumstances and connect Canadians with hundreds of social and legal service providers nationwide.

The Hotline serves an additional function of allowing the Centre to collect and store anonymous data on human trafficking cases that come to the attention of the Hotline. During its first year in operation, the Hotline identified 415 cases of human trafficking involving 593 victims. A “case” refers to a unique situation, event or series of events that prompted an individual to contact the Hotline. In a report released recently by the Centre, the Hotline’s 2019/2020 data revealed several notable findings:

- Almost three-quarters (71%) of human trafficking cases identified by the Hotline involved sexual exploitation

- One-third (32%) of all individuals who contacted the Hotline were victims, while another 26% were family or friends of a victimNote

- Most (90%) victims were female

- Over four in ten (44%) victims who contacted the Hotline were still being trafficked, while a somewhat smaller proportion (39%) had exited the trafficking situationNote

- More than one in ten (14%) victims were born outside of Canada

- One-quarter (26%) of all service referrals were for shelter or housing assistance, 69% of which were for emergency or short-term shelter.

The data collected by the Hotline complements data captured by police and courts, and will help to advance understanding of human trafficking in Canada.

The Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in over 200 different languages, including 27 Indigenous languages. It can be accessed by phone at 1-833-900-1010 or online at: www.canadianhumantraffickinghotline.ca.

End of text box 3

Section 2: Linking police-reported incident and accused persons data

To better understand the nature of human trafficking in Canada it is essential to consider the offending patterns of those who commit such crimes. The Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics at Statistics Canada conducted an internal record linkage using police-reported incident and accused person data files over a 12-year period (2009 to 2020) to determine prior and repeated contact with police among persons accused of human trafficking.Note

This section examines the number of times traffickers came into contact with the police—as persons accused of crime—before and after they were accused of human trafficking, the types of crimes they engaged in, and whether they acted alone or co-offended.Note For more information about the human trafficking record linkage, see Survey description.

The large majority of persons accused of police-reported human trafficking involved in multiple criminal incidents

Between 2009 and 2020, there were 1,793 unique persons accused of police-reported human trafficking, including Criminal Code and IRPA violations. Among these accused persons, eight in ten (81%) were men while two in ten (19%) were women.Note

The large majority (87%) of persons accused of human trafficking were identified by police in multiple criminal incidents (not only human trafficking) between 2009 and 2020, and this was more common among men than women (90% versus 78%). On average, those accused of human trafficking had been implicated in 11 unique criminal incidents between 2009 and 2020. Men had been accused of an average of 12 incidents while women were accused of an average 7 incidents.

Three-quarters of those accused of human trafficking had prior contact with the police

Based on results from the human trafficking record linkage, it is clear that those who were accused of human trafficking had previously been implicated in other criminal activity. Accused persons often had a prior contact with police before their initial human trafficking contact and at least one other contact with police (i.e., a re-contact) after the human trafficking incident.Note Three-quarters (75%) were accused by police in a non-human trafficking incident prior to being accused of the human trafficking incident (Chart 3). As such, many individuals accused of human trafficking were already known to police. Following contact with police for human trafficking, two-thirds (66%) of accused had a re-contact with police during the reference period (human trafficking or not). Differences emerged by gender, where a larger proportion of men than women had a prior contact and a re-contact with police.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Gender | Prior contact with police | Re-contact with police |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | 60 | 56 |

| Men | 78 | 68 |

| TotalData table for chart 3 Note 1 | 75 | 66 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Human trafficking record linkage file. |

||

Chart 3 end

One in nine persons accused of human trafficking implicated in another incident of human trafficking

Among those who had been accused of a crime prior to human trafficking, the vast majority (91%) had been implicated in non-violent incidents.Note Meanwhile, seven in ten (71%) had been accused in violent incidents and nearly two-thirds (65%) were implicated in incidents related to the administration of justice.Note

The non-violent incidents these accused were implicated in were most often related to property crimes (67%) or offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (58%). In terms of violent incidents, accused were most commonly implicated in physical assault-related offences (57%) or other violations involving violence or the threat of violenceNote (47%), while offences related to the deprivation of freedom (9%), sexual offences (9%) and offences related to the sex trade (4%) were relatively less common. Finally, of the incidents related to the administration of justice, these individuals were most often accused of failure to comply (56%), breach of probation (34%) and failure to appear (20%) prior to being implicated in human trafficking.

Following their initial human trafficking contact with police, around one in nine (11%) had been accused of human trafficking again during the reference period, and this was similar among men and women (11% versus 10%).

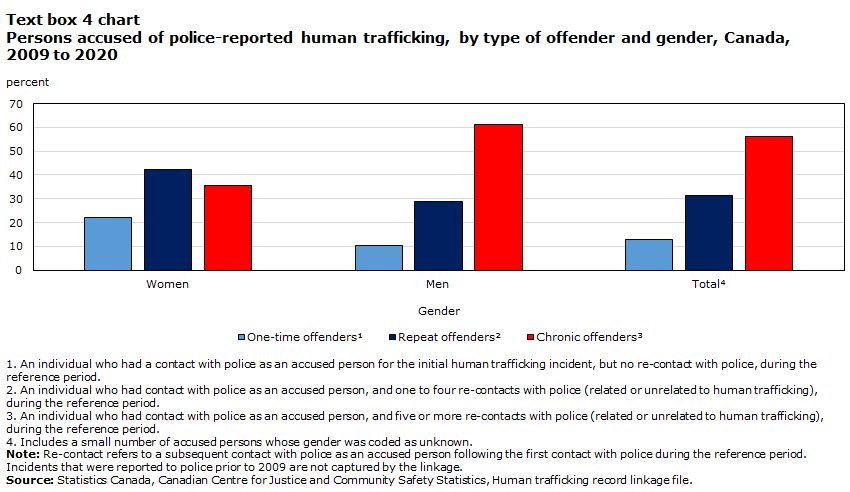

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Exploring re-contact among accused persons

Crime data is often presented as a simple count of criminal incidents and the associated accused persons, which does not provide insight into the volume of crime committed by the same person (Brennan and Matarazzo 2016). Record linkages, such as the one completed for this article, allow for an analysis of multiple contacts with police among unique accused persons to determine patterns of offending behaviour.Note

Among those accused of human trafficking between 2009 and 2020, re-contact with police—that is, subsequent contacts with police after being accused of human trafficking initially—was common. Among those accused of human trafficking during the reference period, more than half (56%) were chronic offenders—meaning they had been accused in six or more criminal incidents (human trafficking or not) between 2009 and 2020 (Text box 4 chart). Chronic offending was more common among men (61%) than women (36%).

Text box Chart start

Data table for Text box table chart

| Gender | One-time offendersData table for Text box 4 chart Note 1 | Repeat offendersData table for Text box 4 chart Note 2 | Chronic offendersData table for Text box 4 chart Note 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Women | 22 | 42 | 36 |

| Men | 10 | 29 | 61 |

| TotalData table for Text box 4 chart Note 4 | 13 | 31 | 56 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Human trafficking record linkage file. |

|||

Text box Chart end

In all, nearly one in three (31%) persons accused of human trafficking were repeat offenders—having been accused of two to five criminal incidents during the reference period. Unlike chronic offending, repeat offending was more common among women (42%) than men (29%).

One-time offending was relatively less common. About one in eight (13%) persons accused of human trafficking had been accused of that single criminal incident between 2009 and 2020. A larger proportion of women (22%) than men (10%) were one-time offenders.

End of text box 4

Just over six in ten persons accused of human trafficking have co-accused

Individuals accused of human trafficking often acted with others in the human trafficking incident. Overall, more than six in ten (63%) accused persons were implicated in human trafficking incidents that involved multiple perpetrators.Note Meanwhile, four in ten (41%) accused persons had been implicated individually.Note These findings align with an analysis of court cases undertaken by the UNODC (2021a), where three-quarters (74%) of the human trafficking incidents examined involved two or more traffickers. Of note, six in ten (61%) multi-trafficker incidents were related to organized crime, either within a business enterprise or a governance structure. Such incidents involved more victims, who were trafficked for a longer duration, and with more force than human trafficking incidents involving a lone trafficker (UNODC 2021a).

Co-accused were more common for women who were accused in human trafficking incidents. The large majority (86%) of women were accused alongside others, while fewer than one in five women (16%) had been accused on their own. This finding supports previous research noting that women traffickers often offend alongside their intimate partners (Broad 2015). On the other hand, compared to women, a smaller proportion of men were accused of human trafficking with others, and a greater proportion were accused on their own (57% and 47%, respectively).

Charges for human trafficking more common among those with prior police contact

As mentioned previously, prior charges among persons accused of human trafficking were common: three-quarters (75%) of those accused had prior contact with police, before the initial human trafficking incident. Of those with prior contact, more than nine in ten (93%) had charges laid or recommended against them in non-human trafficking incidents. Prior charges were more common among men (95%) than women (84%) who were accused of human trafficking.

It was somewhat more common for accused persons to be charged in their initial incident of human trafficking when they had previously been accused of a crime. Among those who had prior contact with police before being implicated in human trafficking, the vast majority (93%) had charges laid or recommended for their initial human trafficking incident. This was consistent for men and women (both 93%). Among those with no prior contact with police, the large majority (85%) were charged for their initial human trafficking incident. This was more common among women (89%) than men (83%) who were accused of this crime.

Section 3: Human trafficking in adult criminal court

Alongside police-reported data, the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) provides official data on human trafficking cases, as reported by the Canadian adult criminal and youth courts. Beyond the initial charge laid, the ICCS provides information on court processing times, charge and case decisions, and sentencing outcomes. As such, this section details information on the adjudication of human trafficking cases in adult criminal court involving Criminal Code offences in Canada, completed between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020 (for information about youth court, see Text box 5).Note Of note, police-reported data and court data will not align perfectly given that some police-reported incidents of human trafficking are processed by way of other charges at the criminal court stage following Crown input.Note In addition, the time periods for police-reported incidents and court cases may differ as court cases are only counted in the ICCS database once all the charges in the case are complete or deemed complete.

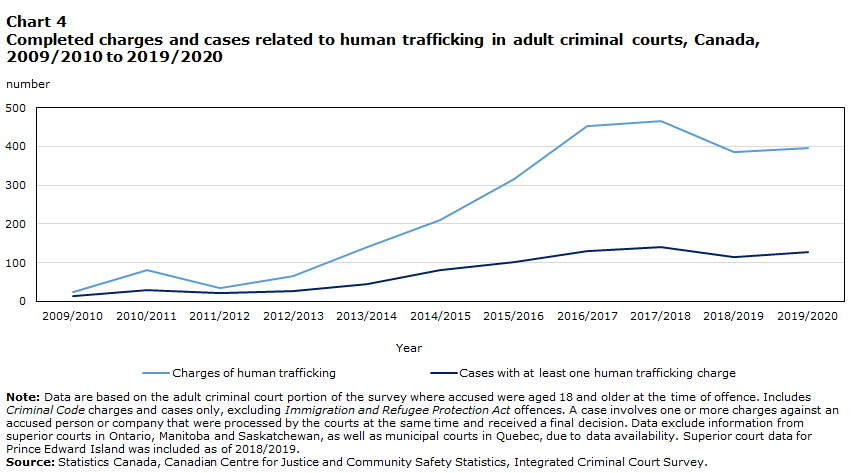

The number of human trafficking cases has increased, but not as much as the number of charges

Between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, 834 cases involving 2,572 human trafficking chargesNote were completed in adult criminal courts in Canada.Note Over this period, the number of human trafficking charges and cases have generally increased year-over-year, peaking in 2017/2018 before tapering off and increasing again in 2019/2020 (Chart 4). More specifically, in 2009/2010, there were 13 cases completed that involved at least one human trafficking charge, totalling 24 charges of human trafficking. In 2019/2020, 128 human trafficking cases and 396 charges were completed, approximately 10 times as many cases and almost 17 times as many charges compared with 2009/2010. Of interest, the number of human trafficking charges per case increased from an average of two charges per case to three during this time.

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Year | Charges of human trafficking | Cases with at least one human trafficking charge |

|---|---|---|

| number | ||

| 2009/2010 | 24 | 13 |

| 2010/2011 | 81 | 30 |

| 2011/2012 | 36 | 21 |

| 2012/2013 | 65 | 28 |

| 2013/2014 | 141 | 45 |

| 2014/2015 | 210 | 82 |

| 2015/2016 | 315 | 103 |

| 2016/2017 | 452 | 129 |

| 2017/2018 | 466 | 140 |

| 2018/2019 | 386 | 115 |

| 2019/2020 | 396 | 128 |

|

Note: Data are based on the adult criminal court portion of the survey where accused were aged 18 and older at the time of offence. Includes Criminal Code charges and cases only, excluding Immigration and Refugee Protection Act offences. A case involves one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final decision. Data exclude information from superior courts in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, as well as municipal courts in Quebec, due to data availability. Superior court data for Prince Edward Island was included as of 2018/2019. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||

Chart 4 end

Human trafficking cases average four times more charges and take twice as long to complete as other violent cases

Between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, completed adult criminal court cases that included at least one charge of human trafficking had an average of 17 charges (human trafficking or otherwise) per case. By comparison, over the same period, cases involving at least one violent offence averaged four charges per case overall.Note Of the 819 multi-charge cases involving human trafficking, three-quarters (76%) also included a sex trade offence, 31% included a charge of kidnapping or forcible confinement and 28% included a sex offence.Note

Multi-charge cases are more complex and, generally speaking, take longer to complete than single-charge cases. This was seen with human trafficking cases, which took almost twice as long to complete than other violent adult criminal court cases. Between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, the median amount of time it took to complete an adult criminal court case involving at least one violent charge was 176 days. In contrast, it took a median of 373 days to complete a case involving at least one human trafficking charge.

Majority of completed human trafficking cases are stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged

From 2009/2010 to 2019/2020, completed adult criminal court cases involving at least one human trafficking charge resulted in a variety of different decision types. For eight in ten (81%) of these cases, the most serious decision rendered on a human trafficking charge was either a stay, a withdrawal, a dismissal or a discharge (Chart 5).Note In comparison, 12% of human trafficking cases resulted in a decision of guilty,Note while 5% resulted in an acquittal and 1% resulted in another decision type, such as being found unfit to stand trial or not criminally responsible. A guilty finding was also less common for completed cases involving at least one sex trade charge (33% of such cases resulted in a guilty decision), as well as those involving violent offence charges (48% of such cases).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Type of decision | Cases with at least one charge of human trafficking | Cases with at least one charge related to the sex trade | Cases with at least one violent offence chargeData table for chart 5 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Guilty | 12 | 33 | 48 |

| Acquitted | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged | 81 | 64 | 44 |

| OtherData table for chart 5 Note 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 5 end

Charges may be withdrawn, dismissed or discharged for numerous reasons. Some research has found that with the implementation of new or amended legislation, prosecutors must navigate an uncertain legal environment, often while lacking case law guidance, and may encounter misunderstanding, biases, or ignorance about human trafficking when interacting with judges and juries (Farrell et al. 2016; Farrell et al. 2014). In addition, human trafficking victims may cooperate initially, but then not consent to subsequent interviews, recant original testimony or disappear before the trial commences thereby increasing the likelihood of prosecutors’ withdrawing or staying charges (Farrell et al. 2019; Farrell et al. 2016; Farrell et al. 2014; Farrell et al. 2010).Note Within an uncertain legal environment and without victim testimony or corroborating evidence, the likelihood of a successful prosecution decreases. Further, charges may be stayed or withdrawn as part of the plea bargaining process in which the accused agrees to participate in diversion or alternative measures, for example, in exchange for having charges stayed or withdrawn (Public Prosecution Service of Canada 2017).

The sentencing information discussed here represents the most serious sentence in the case for the selected offence type that resulted in a guilty decision.Note When cases involving at least one human trafficking charge resulted in a finding of guilt, the most common sentencing outcome was custody (86%). In addition, 13% of these guilty cases resulted in a sentence of probation and 1% received another type of sentence such as an absolute or conditional discharge, or a community service order. In contrast, among violent cases where a guilty decision was in relation to the violent offence, 48% received a probation order, while 38% received a custody order. Remaining sentences included conditional sentences (5%), fines (3%) or another type of sentence (6%).

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

Completed human trafficking cases in youth courts in Canada

Between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, 6% of completed human trafficking cases involved a youth accused—that is, a person between the ages of 12 and 17. During this period, there were 53 cases involving at least one charge of human trafficking completed in youth courts in Canada, with a total of 107 charges.

All but one of the human trafficking cases processed in youth court involved multiple charges. Of the 52 multi-charge cases, 71% included a sex trade offence, 35% included a sexual offence and 35% included a charge of kidnapping or forcible confinement.Note

In cases where the most serious sentence was associated with a finding of guilt for the human trafficking charge, 42% resulted in a sentence of custody and supervision, 17% deferred custody and supervision,Note 33% probation and 8% involved another type of sentence.

End of text box 5

Summary

Between 2010 and 2020, 2,977 incidents of human trafficking have been reported by police services in Canada; at least three in ten (30%) of which involved an international border crossing. The number of incidents increased over time before declining in 2018, peaking in 2019, and declining once again in 2020. The highest provincial rates of police-reported human trafficking in 2020 were documented in Nova Scotia and Ontario, a finding that has generally remained consistent over time.

Police-reported human trafficking in Canada affected women and girls disproportionately, and they represented the vast majority of detected victims. The large majority of accused persons were men and boys, and most victims knew their trafficker.

Just under half of all police-reported human trafficking incidents have been cleared either by charge (44%) or by another means (4%). An accused person has not been identified by police in the remaining incidents.

Between 2009 and 2020, there were 1,793 unique persons accused of police-reported human trafficking, including Criminal Code and Immigrant and Refugee Protection Act violations; about eight in ten of whom were male. The large majority (87%) of accused were identified by police in multiple criminal incidents—both related and unrelated to human trafficking.

According to a data linkage for 2009 to 2020, most accused had been in contact with police either before (75%) or after (66%) being accused of a human trafficking offence. Among prior contacts, accused were most often implicated in property crimes (67%), offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (58%), physical assault-related offences (57%) and the administration of justice offence failure to comply (56%). Following their initial human trafficking contact with police, around one in nine individuals had been accused of human trafficking again during the reference period.

In adult criminal courts in Canada, there were 834 human trafficking cases completed between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020. As the most serious decision in adult criminal court, a finding of guilt was less common for cases involving human trafficking charges (12%) than for those involving sex trade charges (33%) or violent charges (48%). Human trafficking cases took twice as long to process through adult criminal courts than violent offence cases (a median of 373 days versus 176 days).

Detailed data tables

Survey description

Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2020, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada. The count for a particular year represents incidents reported during that year, regardless of when the incident actually occurred.

One incident can involve multiple offences. In order to ensure comparability, aggregate counts are presented based on the most serious offence in the incident as determined by a standard classification rule used by all police services. For human trafficking, Criminal Code offences reflect the most serious violation against the victim and Immigration and Refugee Protection Act offences reflect the most serious violation in the incident. Where further detail is provided—such as characteristics of incidents, victims and accused persons—microdata from the Incident-based UCR are used, for which police services can report up to four violations for each incident. As such, the human trafficking-related offence may or may not be the most serious violation reported by police for the incident.

Given that small counts of victims identified as “gender diverse” may exist, the UCR data available to the public has been recoded to assign these counts to either “female” or “male” in order to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy. Victims and accused persons identified as gender diverse have been assigned to either female or male based on the regional distribution of victims’ and accused persons’ gender.

Human trafficking record linkage

In order to explore prior contacts and repeated contacts (i.e., re-contacts) with police among those accused of human trafficking, a deterministic record linkage was completed. The linkage is based on police-reported data on human trafficking accused persons and incidents between 2009 and 2020, from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. Certain types of crime, like human trafficking, may occur over a period of time, sometimes years. The linkage data reflect the report date of an incident (i.e., when it came to the attention of police); therefore, a small number of human trafficking incidents that occurred prior to 2009 but were reported during the 2009 to 2020 reference period are included in the linkage.

The record linkage paired in-scope police-reported incidents with in-scope police-reported accused persons. All accused persons (i.e., not companies) were considered in-scope if they linked to a police-reported incident during the reference period. From there, those who were accused of human trafficking—either under the Criminal Code or the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act—were linked back to all police-reported incidents based on province or territory, Soundex, date of birth and gender.

In all, the record linkage identified 1,793 unique persons accused of police-reported human trafficking between 2009 and 2020, and they linked to 18,312 criminal incidents (both related and unrelated to human trafficking). The final linkage rate of accused persons, after removing duplicate records and a manual review of potentially false links, was 100%.

Integrated Criminal Court Survey

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey collects statistical information on adult and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences.

All adult courts have reported to the adult component of the survey since the 2005/2006 fiscal year, with the exception of superior courts in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, as well as municipal courts in Quebec. These data were not available for extraction from the provinces' electronic reporting systems and therefore, were not reported to the survey. Superior court data for Prince Edward Island was included as of 2018/2019.

The primary unit of analysis is a case. A case is defined as one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final decision. A case combines all charges against the same person having one or more key overlapping dates (date of offence, date of initiation, date of first appearance, date of decision or date of sentencing) into a single case.

References

Altun, S., Abas, M., Zimmerman, C., Howard, L. M. and S. Oram. 2017. “Mental health and human trafficking: Responding to survivors’ needs.” British Journal of Psychiatry International. Vol. 14, no. 1.

Baird, K., McDonald, K. and J. Connolly. 2020. “Sex trafficking of women and girls in a southern Ontario region: Police file review exploring victim characteristics, trafficking experiences, and the intersection with child welfare.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. Vol. 52, no. 1.

Barrett, N. A. 2013. An assessment of sex trafficking. Canadian Women’s Foundation.

Boyce, J., Te, S. and S. Brennan. 2018. “Economic profiles of offenders in Saskatchewan.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Brennan, S. and A. Matarazzo. 2016. “Re-contact with the Saskatchewan justice system.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Broad, R. 2015. “A vile and violent thing: Female traffickers and the criminal justice response.” British Journal of Criminology. Vol. 55, no. 6.

Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking (CCTEHT). 2021a. Human trafficking corridors in Canada.

Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking (CCTEHT). 2021b. Human trafficking trends in Canada: 2019-2020.

Casassa, K., Knight, L. and C. Mengo. 2021. “Trauma bonding perspectives from service providers and survivors of sex trafficking: A scoping review.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

Cotter, A. 2020. “Trafficking in persons in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice. 2015. A Handbook for Criminal Justice Practitioners on Trafficking in Persons.

Farrell, A., Dank, M., de Vries, I., Kafafian, M., Hughes, A. and S. Lockwood. 2019. “Failing victims? Challenges of the police response to human trafficking.” Criminology and Public Policy. Vol. 18.

Farrell, A., DeLateur, M. J., Owens, C. and S. Fahy. 2016. “The prosecution of state-level human trafficking cases in the United States.” Anti-Trafficking Review. Vol. 6.

Farrell, A., Owens, C. and J. McDevitt. 2014. “New laws but few cases: Understanding the challenges to the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases.” Crime, Law and Social Change. Vol. 61.

Farrell, A., McDevitt, J. and S. Fahy. 2010. “Where are all the victims? Understanding the determinants of official identification of human trafficking incidents.” American Society of Criminology. Vol. 9, no. 2.

Ibrahim, D. 2022. “Canadian residential facilities for victims of abuse, 2020/2021.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Ibrahim, D. 2021. “Trafficking in persons in Canada, 2019.” Juristat Bulletin—Quick Fact. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-005-X.

International Labor Organization. 2017. Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage.

Kiensat, J., Lakner, M. and A. Neulet. 2014. Role of female offenders in sex trafficking organizations. Regional Academy on the United Nations.

Luz, V. 2020. Why victims and survivors of human trafficking may choose not to report. Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking.

Millar, H., O’Doherty, T. and K. Roots. 2017. “A formidable task: Reflections on obtaining empirical evidence on human trafficking in Canada.” Anti-Trafficking Review. Vol. 8.

Parliament of Canada. 2018. Moving forward in the fight against human trafficking in Canada. House of Commons. Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. 42nd Parl., 1st sess.

Public Prosecution Service of Canada. 2017. Public Prosecution Service of Canada Deskbook.

Public Safety Canada. 2020a. About human trafficking.

Public Safety Canada. 2020b. Actions to combat human trafficking.

Public Safety Canada. 2019. National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking: 2019-2024.

Ross, C., Dimitrova, S., Howard, L. M., Dewey, M., Zimmerman, C. and S. Oram. 2015. “Human trafficking and health: A cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals’ contact with victims of human trafficking.” British Medical Journal Open. Vol. 5.

Statistics Canada. 2022. Table 17-10-0005-01 – Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2021a. Global report on trafficking in persons.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2021b. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on trafficking in persons and responses to the challenges.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2020. Female victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation as defendants.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). n.d. How COVID-19 restrictions and the economic consequences are likely to impact migrant smuggling and cross-border trafficking in persons to Europe and North America.

Ward, T. and S. Fouladvand. 2018. “Human trafficking, victims’ rights and fair trials.” The Journal of Criminal Law. Vol. 82, no. 2.

Women’s Shelters Canada. 2020. “Special issue: The impact of COVID-19 on VAW shelters and transition houses.” Shelter Voices.

- Date modified: