Section 1: Police-reported family violence against children and youth in Canada, 2018

by Shana Conroy

Police-reported family violence against children and youth increased since 2017

- In 2018, there were 60,651 child and youth victims (aged 17 and younger) of police-reported violence in Canada.Note Of these victims, 57% were female and 43% were male. Overall, child and youth victims of violence were most often victimized by a casual acquaintance (32%) or a family member (31%), while a stranger (17%) was relatively less common (Table 1.1).

- For the 18,965 child and youth victimized by a family member, a parent (59%) was the most common perpetrator, followed by another type of family member—such as a grandparent, uncle or aunt—or a sibling (24% and 16%, respectively). This pattern applied for both female and male victims (Table 1.1).

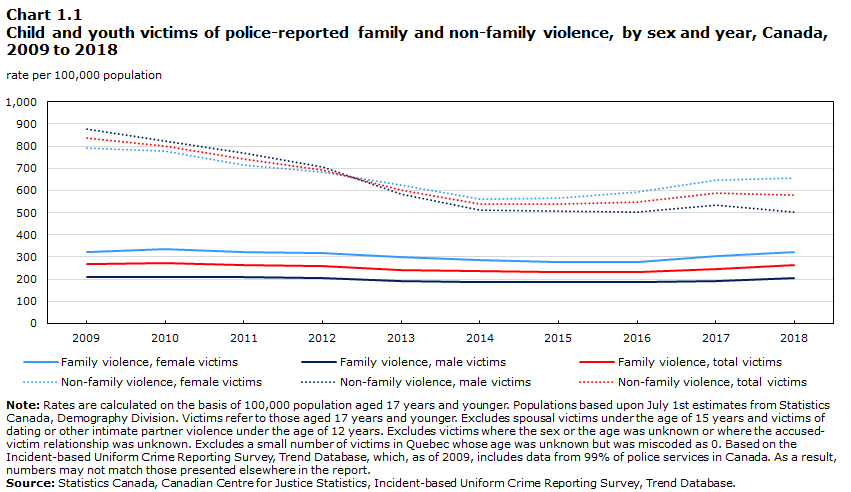

- Between 2017 and 2018, family violence against children and youth increased by 7% while non-family violence slightly decreased (-2%). Between 2009 and 2018, family violence against children and youth remained fairly stable (-1%) as non-family violence had a relatively large decrease (-31%) (Chart 1.1).Note

Data table for Chart 1.1

| Year | Family violence | Non-family violence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| female victims | male victims | total victims | female victims | male victims | total victims | |

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||||

| 2009 | 324 | 211 | 266 | 791 | 878 | 835 |

| 2010 | 337 | 210 | 272 | 778 | 823 | 801 |

| 2011 | 324 | 209 | 265 | 716 | 768 | 743 |

| 2012 | 317 | 203 | 259 | 682 | 704 | 693 |

| 2013 | 298 | 191 | 243 | 624 | 584 | 603 |

| 2014 | 286 | 188 | 236 | 563 | 512 | 537 |

| 2015 | 277 | 185 | 230 | 567 | 509 | 538 |

| 2016 | 277 | 186 | 231 | 593 | 505 | 548 |

| 2017 | 305 | 192 | 247 | 646 | 532 | 588 |

| 2018 | 324 | 206 | 264 | 655 | 504 | 578 |

|

Note: Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population aged 17 years and younger. Populations based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Demography Division. Victims refer to those aged 17 years and younger. Excludes spousal victims under the age of 15 years and victims of dating or other intimate partner violence under the age of 12 years. Excludes victims where the sex or the age was unknown or where the accused-victim relationship was unknown. Excludes a small number of victims in Quebec whose age was unknown but was miscoded as 0. Based on the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database, which, as of 2009, includes data from 99% of police services in Canada. As a result, numbers may not match those presented elsewhere in the report. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. |

||||||

Police-reported family-related sexual offences nearly five times higher for female children and youth than male counterparts

- In 2018, the rate of police-reported family violence against children and youth was 266 per 100,000 population. Family violence increased with victim age: there were 159 victims aged 5 and younger per 100,000 population, while there were 379 victims aged 15 to 17 per 100,000 population. It is important to note that the victimization of children and youth is often difficult to detect—particularly in the context of family violence—and police-reported data are likely an underestimation of the true extent of the issue. For instance, younger victims are unique in that they may be unaware that they are being victimized, may not know how to seek help, may be unable to report their victimization and may be dependent on the perpetrator (Table 1.2).

- Among child and youth victims of family violence, the rate of physical assaultNote was higher than the rate for sexual offencesNote (145 and 90 per 100,000 population, respectively). While the rate for physical assault was highest among victims aged 15 to 17 (236), the rate for sexual offences peaked among those aged 12 to 14 (132) (Table 1.2).

- Differences in the type of family violence experienced emerged depending on the sex of the victim: while female and male victims had similar rates for physical assault (143 versus 148 per 100,000 population), the rate for sexual offences was nearly five times higher for female victims than male victims (149 versus 32) (Table 1.2).

Police-reported family violence against children and youth more often cleared by charge than non-family violence

- Regardless of the type of violation, police-reported family violence against children and youth was more often cleared by charge—or charge recommended—than non-family violence. In terms of incidents cleared by charge, the largest difference between victims of family and non-family violence was for other offences involving violence or the threat of violenceNote (60% versus 32%), followed by sexual offences (44% versus 37%) and physical assault (41% versus 36%) (Table 1.3).

- Among child and youth victims of family violence, incidents most often remained not cleared when they were sexual offences (44%). This was less common for physical assault (30%) and other offences involving violence or the threat of violence (21%). A larger proportion of sexual offence incidents remained not cleared for male victims of family violence than for their female counterparts (49% versus 43%) (Table 1.3).

Majority of child and youth victims of police-reported family violence live with the person who victimized them

- The vast majority of child and youth victims of police-reported family violence were victimized at a residential location (91% of females and 90% of males) (Table 1.4).

- Of the child and youth victims of family violence at a residential location, the majority lived with the person who victimized them, and this was somewhat more common for male victims than their female counterparts (69% versus 60%). A further 16% of female victims and 13% of male victims experienced violence in their own home where the accused did not live (Table 1.4).

- Among child and youth victims who experienced family violence at a residential location, it was more common for males to live with the accused—regardless of the type family relationship—than their female counterparts. Among males, 75% lived with the parent, 72% lived with the sibling and 42% lived with another family member who victimized them (compared with 73%, 62% and 34% of females, respectively) (Table 1.4).

Physical force often used against child and youth victims of police-reported family violence

- Physical force was used against three-quarters (75%) of child and youth victims of police-reported family violence. Approximately one in six (15%) child and youth victims of family violence were involved in incidents where a weapon was present, and the presence of a firearm was rare (1%) (Table 1.5).Note

- Despite the use of physical force or the presence of a weapon in 91% of incidents, six in ten (62%) child and youth victims of family violence had no physical injury as a result of the incident they experienced. Meanwhile, of the four in ten (38%) that did have a physical injury, nearly all were minor in nature. An injury was more common for male victims of family violence than their female counterparts (45% versus 34%). It is not possible to determine the short- and long-term emotional impacts of violent victimization with police-reported data (Table 1.5).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1.1

Self-reported experiences of harsh parenting

In 2018, Statistics Canada conducted the Survey of Safety in Private and Public Spaces (SSPPS) as part of It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-based Violence. Canadians aged 15 and older were asked about their experiences of inappropriate sexual behaviour at home, in the workplace, in public and online, as well as experiences of physical and sexual assault. The SSPPS also included retrospective questions about harsh parenting experienced before age 15. While certain forms of harsh parenting may not be considered a criminal act, research has noted that early caregiving can have a significant impact on the well-being and development of a child.Note

On the topic of harsh parenting, the SSPPS asked the following:

Before age 15…did your parents or other caregivers do any of the following?

- Spank you with their hand or slap you on the hand?

- Say things that really hurt your feelings?

- Made you feel like you were not wanted or loved?

- Did not take care of your basic needs, such as keeping you clean or providing food or clothing?

Among those living in the provinces, 64% of Canadians stated that they had experienced some form of harsh parenting (65% of women and 62% of men). The most common type of harsh parenting was spanking or slapping (experienced by 55% of Canadians overall), followed by hurt feelings (38%), feeling unwanted or unloved (19%) and unmet basic needs (4%). This pattern was the same for both women and men.

End of text box 1

Perpetrators of police-reported family violence against children and youth most often aged 18 to 44

- Of all perpetrators of police-reported violence against children and youth, 34% of female accused and 30% of male accused victimized a family member. For every 100,000 population, there were 9 females and 31 males accused of family violence against children and youth (Table 1.6).Note

- Overall, those accused of family violence against children and youth were most commonly aged 18 to 44 (34 per 100,000 population). This pattern applied to both female and male accused (Table 1.6).

Police-reported family violence against children and youth increased in nearly all provinces and territories since 2017

- Among the provinces, the rate of police-reported family violence against children and youth was highest in Saskatchewan (453 per 100,000 population), Manitoba (370) and Quebec (368), while it was lowest in Ontario (182), British Columbia (200) and Alberta (244). Similar to crime in general, rates of family violence against children and youth were highest in the territories (Table 1.7).

- Similar to non-family violence, rates of family violence against and children and youth were higher for female victims than their male counterparts in every province and territory. The largest differences between female and male victims were noted in the Northwest Territories (1,647 versus 723), Manitoba (483 versus 262), Nunavut (1,845 versus 1,001) and New BrunswickNote (434 versus 241) (Table 1.7).

- Between 2017 and 2018, police-reported family violence increased in every province and territory, with the exception of Saskatchewan (-7%), which had the highest rate among the provinces in 2018, and Alberta (-1%). The largest increase was noted in Prince Edward Island (+62%) followed by the Northwest Territories (+21%) and Yukon (+12%); however, given the relatively small number of victims in these respective areas, any change in the counts impacts the rate significantly. The overall increase in Yukon was attributable to a 30% increase for female victims while there was a 7% decrease for male victims (Table 1.7).Note

Rural rates of police-reported family violence against children and youth nearly twice as high as urban rates

- In 2018, police-reported family violence against children and youth was nearly twice as high in rural areas than urban areas (448 versus 227 per 100,000 population). This pattern applied for female and male victims of family violence, although the rural-urban difference was larger for females (566 versus 276) than males (336 versus 180) (Table 1.8).Note

- The rate of family violence against children and youth was lower in Canada’s largest cities—referred to as census metropolitan areas or CMAs—than it was in non-CMAs (207 versus 413 per 100,000 population).Note Family violence against children and youth was highest in Saguenay, Trois-Rivières, Halifax and Gatineau (451, 389, 361 and 359, respectively), while it was lowest in Kelowna, Barrie, Ottawa and Guelph (98, 123, 129 and 129, respectively) (Table 1.9).

- Rates of violence were higher for females in every CMA. The difference between females and males was largest in Guelph (198 versus 63 per 100,000 population) and Greater Sudbury (443 versus 160) (Table 1.9).

Family-related homicide against children and youth most commonly motivated by frustration, anger or despair

- Family-related homicides occur within complex interpersonal contexts that often involve a history of violence.Note Between 2008 and 2018, the most common primary motive for family-related homicide involving child and youth victims was by far frustration, anger or despair (61%). Regardless of age group, this remained the most common motive for family-related homicide involving child and youth victims. For victims aged 12 to 14 and victims aged 15 to 17, an argument or quarrel was also common (19% and 24%, respectively) (Table 1.10).

- Children and youth are more commonly victims of family-related homicide than non-family homicide (2.23 versus 1.81 per 1 million population). Between 2008 and 2018, the rate of family-related homicide against children and youth decreased by 38%, from 3.59 to 2.23 per 1 million population (a decrease from 25 victims in 2008 to 16 victims in 2018) (Table 1.11).

Detailed data tables

- Date modified: