Health Reports

The ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and screen time among Canadian youth

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202301000001-eng

Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused changes in health behaviours, including participation in physical activity and screen time. The purpose of this paper is to examine trends in physical activity and screen time among Canadian youth from January 2018 to February 2022.

Methods

The Canadian Community Health Survey asks Canadian youth (aged 12 to 17 years) to report the time they spend active by domain: recreation, transportation, school and household. Survey respondents are also asked to report their screen time on school days and non-school days. The present analysis compares the physical activity from four cross-sectional samples collected during 2018 (January to December; n=3,952), January to March 2020 (n=911), September to December 2020 (n=1,573), and January 2021 to February 2022 (n=3,501). Screen time is compared between 2018 and 2021/2022. Sub‑annual descriptive analyses examine how physical activity and screen time varied within and between these years.

Results

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, half of Canadian youth met the physical activity recommendation (2018: 49.6%; January to March 2020: 53.7%). The percentage meeting the recommendation dropped in the first year of the pandemic (September to December 2020: 37.3%) and recovered slightly in 2021 (43.8%). From 2018 to 2021, total physical activity dropped by 8.3 minutes per day (58.1 minutes per week) among girls and by 2.1 minutes per day (14.7 minutes per week) among boys. The percentage of youth meeting the screen time recommendation on school days dropped from 40.7% in 2018 to 29.1% in 2021 and from 21.4% in 2018 to 13.2% in 2021 on non-school days.

Interpretation

The COVID-19 pandemic had a detrimental impact on the physical activity and screen time of youth, in particular among girls. This analysis provides an update on how the pandemic has continued to affect the physical activity and screen habits of youth in 2020, 2021, and early 2022.

Keywords

movement, exercise, sport, physical education, television, remote learning

Authors

Rachel C. Colley is with the Health Analysis Division at Statistics Canada. Travis J. Saunders is with the University of Prince Edward Island.

What is already known on this subject?

- Physical activity decreased during the 2020 and 2021/2022 pandemic years because of public health restrictions put in place to reduce virus transmission.

- A decline in physical activity was observed among Canadian youth from the fall of 2018 to the fall of 2020.

What does this study add?

- The percentage of boys meeting the physical activity recommendation dropped from 2018 to 2020 and then rebounded in 2021/2022. The percentage of girls meeting the physical activity recommendation dropped from 2018 to 2020 with no rebound evident in 2021/2022.

- The percentage of youth meeting the screen time recommendation was lower in 2021/2022 compared with 2018 on school days and non-school days. The drop was greater among girls than boys.

- Physical activity throughout the year was more variable in 2021/2022 compared with 2018, in particular among boys. These increases and decreases seem to coincide with specific waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- From 2018 to 2021/2022, many youth appear to have shifted from meeting the screen time recommendations (two hours or less per day) to using screens for four hours or more per day.

Introduction

Lockdowns and closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic altered the exercise and screen time habits of Canadians. A previous analysis reported that physical activity decreased by 14 percentage points among Canadian youth from the fall of 2018 to the fall of 2020.Note 1, Note 2 Other surveys of Canadian children and youth also reported decreased physical activity and increased screen time during the first year of the pandemic.Note 3, Note 4, Note 5, Note 6 These findings are especially concerning given that only a minority of Canadian youth were meeting screen time and physical activity recommendations before the pandemic, with boys typically reporting higher levels of physical activity and screen time.Note 7 These results are important given that physical activity is a key determinant of health, and youth who engaged in more physical activity and sleep while reducing screen time during the pandemic had lower depression scores, less severe emotional dysregulation, and better subjective well-being.Note 8 Certain youth may have been more affected, as evidenced in a recent report noting that 10% of 6- to 12-year-old girls have not returned to sports since the onset of the pandemic, and one in three girls aged 13 to 18 years currently engaged in sports is unsure if she will continue to participate in sports.Note 9 It is unknown whether the initial decline in physical activity observed in 2020 continued, stabilized, or improved in 2021 and early 2022.

It is important to track ongoing trends in physical activity and screen time among Canadians to determine whether lifestyle habits have reverted to pre-pandemic levels. The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) is an annual cross-sectional survey that collects information on health status, health care use and health determinants for the Canadian population. Information about physical activity was collected from CCHS participants during the pandemic from September to December 2020 and from January 2021 to February 2022 using the same questionnaire modules that were used with participants before the pandemic (January to December 2018 and January to March 2020). This continuity in questionnaire content facilitates a comparison between periods before and during the pandemic. The purpose of this study is to give an update on the screen time and physical activity habits of Canadian youth in 2021 by providing a comparison with values previously reported before and during the first year of the pandemic. This study takes a focused look at how the physical activity and screen time of boys and girls were affected differently.

Methods

Data source

The present analysis presents self-reported data on physical activity and screen time data for Canadian youth aged 12 to 17 years from the CCHS. Estimates were compared between 2018 (n=3,952), early 2020 (n=911), late 2020 (n=1,573) and 2021 (n=3,501). Data are also presented by 2018, 2020 and 2021 collection periods (figures 2 to 7). Collection periods are approximately three months long and are each representative of the Canadian population. The pandemic had major impacts on data collection operations for the 2020 CCHS, including a pause on data collection from April to August 2020. Important analytical and data quality implications related to the 2020 data are described elsewhere.Note 1, Note 10 Importantly, the response rate during the pandemic was much lower than before the pandemic: 58.8% in 2018, 45.6% in January to March 2020, 27.4% in September to December 2020, and 28.4% in January 2021 to February 2022. Data for 2020 were divided into two categories: before the pandemic (January to March 2020) and during the pandemic (September to December 2020). Physical activity and screen time data were not collected in 2019 in a nationally representative sample and therefore were not included in the present analysis. In addition, screen time data were not collected on a nationally representative sample in 2020. The 2018, early 2020, late 2020, and 2021 samples had a similar average age (range for all time points: 14.3 to 14.4 years) and were split evenly by sex (range for all time points: 48.6% to 49.1% female). The percent distribution across rural and small, medium, and large population centres did not vary between time points, nor did the distribution across levels of household income (data not shown).

Physical activity and screen time questions

CCHS respondents were asked to provide estimates of time spent in the past seven days engaged in transportation, recreational, occupational or household, and school-based physical activity. Based on an outlier analysis, values greater than two hours per day of any domain were flagged as outliers and recoded to two hours (occurred in less than 4% of respondents). Youth were classified as meeting the physical activity recommendation if their average daily quantity of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (including all domains of physical activity) was equal to or greater than 60 minutes.Note 11, Note 12 Respondents were asked to estimate their average daily screen time during free time (two hours or less per day, more than two to less than four hours per day, four to less than six hours per day, six to less than eight hours per day, and eight hours or more per day) for days that they went to school and days they did not go to school. Screen time categories were recoded to two hours or less per day, more than two to less than four hours per day, and four hours or more per day. Youth reporting that they accumulated two hours or less of screen time per day were classified as meeting the screen time recommendation.Note 11, Note 12 Questions and response options for physical activity and screen time were consistent across all time points.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to produce means of minutes of physical activity and weighted percentages of the proportion meeting the physical activity and screen time recommendations in the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines. Variance of the estimates was examined using 95% confidence intervals with bootstrap weights applied. Survey weights were applied to the data to address non-response bias and to make the results representative of the Canadian population. Analyses were conducted using SAS (Version 9.4), and differences between the four periods were tested using contrast statements within the PROC DESCRIPT procedure in SAS-callable SUDAAN (Version 11.0.3). Results by collection period were included to provide a picture of the seasonality effect on physical activity and align the picture with key milestones of the pandemic. Statistical testing for differences was completed on four time points: 2018, 2020 before the pandemic, 2020 during the pandemic, and 2021/2022 during the pandemic.

Results

Before the pandemic, half of Canadian youth met the physical activity recommendation (2018: 49.6%; January to March 2020: 53.7%) (Table 1). More boys than girls were meeting the physical activity recommendation before the pandemic (54.3% versus 44.7%). The percentage meeting the recommendation dropped in the first year of the pandemic (September to December 2020: 37.3%) and recovered slightly in 2021 (43.8%). Among boys, the percentage meeting the physical activity recommendation decreased 20 percentage points from early 2020 to the fall of 2020 (60.0% to 39.5%), then increased in 2021 to 52.2%. Among girls, the percentage meeting the physical activity recommendation decreased 12 percentage points from early 2020 to the fall of 2020 (47.1% to 34.8%), then remained at this lower level in 2021, at 35.0%. From 2018 to 2021, total physical activity dropped by 8.3 minutes per day (58.1 minutes per week) among girls and by 2.1 minutes per day (14.7 minutes per week) among boys. This sex difference was largely explained by a greater drop in recreation (-25.2 minutes per week) and active transportation (‑39.2 minutes per week) among girls compared with boys (recreation: -4.9 minutes per week; active transportation: -21.7 minutes per week). The difference between 2018 and 2021 was similar between boys and girls for school and household or occupational physical activity.

| January to December 2018 |

January to March 2020 |

September to December 2020 |

January 2021 to February 2022 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=3,952 | n=911 | n=1,573 | n=3,501 | |||||||||

| % or mean |

95% confidence interval |

% or mean |

95% confidence interval |

% or mean |

95% confidence interval |

% or mean |

95% confidence interval |

|||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | from | to | |||||

| Percentage meeting the physical activity recommendation (%) | ||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 49.6 | 47.3 | 51.9 | 53.7 | 49.5 | 58.0 | 37.2Table 1 Note †† | 34.2 | 40.3 | 43.8Table 1 Note †† | 41.2 | 46.4 |

| Boys | 54.3 | 51.2 | 57.4 | 60.0 | 53.9 | 65.8 | 39.5Table 1 Note †† | 35.5 | 43.8 | 52.2 | 48.6 | 55.9 |

| Girls | 44.7 | 41.3 | 48.1 | 47.1 | 41.3 | 53.1 | 34.8Table 1 Note †† | 30.6 | 39.2 | 35.0Table 1 Note †† | 31.7 | 38.4 |

| Total physical activity (minutes per day) |

||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 72.3 | 69.5 | 75.1 | 75.1 | 70.2 | 80.0 | 56.3Table 1 Note †† | 52.6 | 60.0 | 67.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 63.8 | 70.4 |

| Boys | 80.3 | 76.0 | 84.6 | 81.8 | 74.4 | 89.1 | 61.0Table 1 Note †† | 55.4 | 66.5 | 78.3 | 73.0 | 83.6 |

| Girls | 63.8 | 60.1 | 67.6 | 68.1 | 61.6 | 74.7 | 51.5Table 1 Note †† | 46.5 | 56.4 | 55.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 51.8 | 59.2 |

| Recreational physical activity (minutes per day) |

||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 29.8 | 28.3 | 31.4 | 29.1 | 26.3 | 32.0 | 20.3Table 1 Note †† | 18.5 | 22.1 | 27.6 | 25.7 | 29.6 |

| Boys | 33.9 | 31.6 | 36.2 | 31.5 | 27.4 | 35.5 | 23.3Table 1 Note †† | 20.5 | 26.0 | 33.2 | 30.3 | 36.1 |

| Girls | 25.4 | 23.3 | 27.5 | 26.7 | 22.6 | 30.7 | 17.2Table 1 Note †† | 14.9 | 19.5 | 21.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 19.5 | 24.2 |

| Active transportation (minutes per day) |

||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 24.8 | 23.3 | 26.3 | 23.1 | 20.4 | 25.7 | 19.6Table 1 Note †† | 17.8 | 21.4 | 20.4Table 1 Note †† | 18.8 | 22.0 |

| Boys | 25.9 | 23.6 | 28.1 | 24.7 | 20.6 | 28.9 | 19.4Table 1 Note †† | 16.9 | 21.9 | 22.7 | 20.1 | 25.4 |

| Girls | 23.6 | 21.5 | 25.7 | 21.3 | 18.2 | 24.4 | 19.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 17.2 | 22.3 | 17.9Table 1 Note †† | 16.3 | 19.6 |

| School-based physical activity (minutes per day) |

||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 19.1 | 18.0 | 20.3 | 22.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 19.9 | 24.0 | 13.0Table 1 Note †† | 11.6 | 14.5 | 13.8Table 1 Note †† | 12.8 | 14.9 |

| Boys | 21.1 | 19.3 | 22.8 | 23.6 | 20.7 | 26.5 | 14.6Table 1 Note †† | 12.4 | 16.8 | 16.4Table 1 Note †† | 14.7 | 18.2 |

| Girls | 17.0 | 15.4 | 18.6 | 20.2 | 17.4 | 22.9 | 11.4Table 1 Note †† | 9.5 | 13.3 | 11.2Table 1 Note †† | 10.0 | 12.4 |

| Household/occupation physical activity (minutes per day) |

||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 4.9 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 4.6Note E: Use with caution | 3.0 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 6.4 | 6.9Table 1 Note †† | 5.9 | 7.9 |

| Boys | 5.4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 6.0Note E: Use with caution | 3.2 | 8.7 | 5.7Note E: Use with caution | 3.7 | 7.7 | 7.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 6.1 | 9.4 |

| Girls | 4.3 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 3.2Note E: Use with caution | 1.5 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 6.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.8 | 7.2 |

E use with caution

Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2018, 2020 and 2021. |

||||||||||||

The percentage of youth meeting the screen time recommendation on school days dropped from 40.7% in 2018 to 29.1% in 2021 and on non-school days from 21.4% in 2018 to 13.2% in 2021 (Table 2). Like physical activity, the drop was more pronounced among girls compared with boys on school and non-school days. Overall, a shift in youth from accumulating two hours or less per day of screen time (and meeting the screen time recommendation) (-11.6 percentage points) to accumulating four hours or more per day of screen time (+12.6 percentage points) occurred on school and non-school days and among boys and girls. Fewer youth met the screen time recommendation on non-school days (weekends) compared with school days in both 2018 and 2021.

| 2018 | 2021 | Difference between 2021 and 2018 (% points) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% confidence interval |

% | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | ||||

| School days | |||||||

| Both sexes | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 40.7 | 38.4 | 43.0 | 29.1Table 2 Note †† | 26.9 | 31.5 | -11.6 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 38.2 | 36.0 | 40.4 | 37.1 | 34.6 | 39.7 | -1.1 |

| Four hours or more per day | 21.1 | 19.3 | 23.1 | 33.7Table 2 Note †† | 31.2 | 36.3 | 12.6 |

| Boys | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 37.8 | 34.7 | 40.9 | 28.6Table 2 Note †† | 25.4 | 31.9 | -9.2 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 39.3 | 36.2 | 42.6 | 38.4 | 34.9 | 42.2 | -0.9 |

| Four hours or more per day | 22.9 | 20.3 | 25.7 | 33.0Table 2 Note †† | 29.4 | 36.8 | 10.1 |

| Girls | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 43.8 | 40.4 | 47.2 | 29.8Table 2 Note †† | 26.7 | 33.1 | -14.0 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 37.0 | 33.9 | 40.2 | 35.7 | 32.3 | 39.3 | -1.3 |

| Four hours or more per day | 19.2 | 16.6 | 22.1 | 34.5Table 2 Note †† | 31.0 | 38.2 | 15.3 |

| Both sexes | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 21.4 | 19.7 | 23.2 | 13.2Table 2 Note †† | 11.6 | 15.0 | -8.2 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 31.6 | 29.6 | 33.6 | 30.4 | 28.1 | 32.8 | -1.2 |

| Four hours or more per day | 47.0 | 44.7 | 49.3 | 56.4Table 2 Note †† | 53.9 | 58.9 | 9.4 |

| Boys | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 20.1 | 17.8 | 22.6 | 14.0Table 2 Note †† | 11.7 | 16.8 | -6.1 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 29.5 | 26.8 | 32.4 | 30.1 | 27.0 | 33.4 | 0.6 |

| Four hours or more per day | 50.3 | 47.2 | 53.5 | 55.8Table 2 Note ‡ | 52.3 | 59.3 | 5.5 |

| Girls | |||||||

| Two hours or less per day | 22.8 | 20.3 | 25.5 | 12.3Table 2 Note †† | 10.2 | 14.8 | -10.5 |

| More than two to less than four hours per day | 33.7 | 30.7 | 36.8 | 30.7 | 27.4 | 34.2 | -3.0 |

| Four hours or more per day | 43.5 | 40.2 | 46.9 | 57.0Table 2 Note †† | 53.3 | 60.5 | 13.5 |

|

|||||||

Figure 1 depicts a more detailed change over time from 2018 to early 2022 in the percentage of youth meeting the physical activity recommendation. Data were not available in 2019 or in mid-2020 when the pandemic first hit, and these periods are noted using dotted lines. The percentage meeting recommendations remained relatively stable in all pre-pandemic periods (2018 and January to March 2020), except for a drop during the 2018 summer months. Late 2020 and early 2021 data show a relatively stable lower percentage of boys meeting the recommendation compared with before the pandemic, while another decrease was observed among girls in early 2021 (26.5% meeting the recommendation). Finally, increases were observed in the percentage of boys meeting the recommendations throughout the summer and fall of 2021 (48.9% in March to April vs. 65.6% in September to November), followed by another drop in November 2021 to February 2022 (49.3%). Among girls, the proportion meeting recommendations was the same in March to April 2021 as in November 2021 to February 2022, with relatively little variability in between.

Description of Figure 1

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Before the pandemic | ||

| 2018 | ||

| Jan. to Mar. | 52.4 | 45.9 |

| Apr. to June | 60.4 | 46.8 |

| July to Sept. | 49.6 | 39.7 |

| Oct. to Dec. | 55.3 | 46.4 |

| 2019 | ||

| Jan. to Dec. | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| Jan. 2 to Mar. 13 | 60.0 | 47.1 |

| 1st wave | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Mar. 14 to Aug. 31 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2nd wave (Beta) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| Sept. 1 to 30 | 36.9 | 31.3 |

| Oct. 1 to Nov. 4 | 42.1 | 36.5 |

| Vaccination begins | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Nov. 5 to Dec. 12 | 39.8 | 36.3 |

| 2021 | ||

| Jan. to Feb. | 40.1 | 26.5 |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Mar. to Apr. | 48.9 | 37.3 |

| June to Aug. | 57.1 | 34.9 |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Sept. to mid-Nov. | 65.6 | 40.8 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||

| Mid-Nov. 2021 to Feb. 2022 | 49.3 | 37.3 |

|

... not applicable Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2018, 2020 and 2021. |

||

Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 illustrate the detailed trends in total, recreational, and school physical activity, as well as in active transportation. Total physical activity among boys in the fall of 2021 (93.1 minutes per day) was higher than any values reported before the pandemic, but dropped at the onset of the Omicron wave to a level similar to that of fall 2018 (before the pandemic) (Figure 2). Total physical activity among girls increased steadily across 2021 until dropping slightly at the onset of the Omicron wave (Figure 2). Figure 3 depicts a recovery in recreation-based physical activity in 2021 among boys, with an increase among girls in the summer of 2021 followed by a decrease back to the level observed early in the pandemic. Figure 4 depicts the expected drops in school-based physical activity during the summer months before and during the pandemic (2020 and 2021). School-based physical activity increased in the fall of 2021 when classes resumed; however, school physical activity decreased with the onset of the Omicron wave among boys and girls. Active transportation dropped in early 2021, increased in the summer of 2021, then decreased slightly towards the end of 2021 (Figure 5).

Description of Figure 2

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| average daily minutes of physical activity | ||

| Before the pandemic | ||

| 2018 | ||

| Jan. to Mar. | 75.2 | 65.6 |

| Apr. to June | 88.3 | 69.6 |

| July to Sept. | 74.6 | 54.4 |

| Oct. to Dec. | 83.4 | 66.1 |

| 2019 | ||

| Jan. to Dec. | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| Jan. 2 to Mar. 13 | 81.8 | 68.1 |

| 1st wave | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Mar. 14 to Aug. 31 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2nd wave (Beta) | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Sept. 1 to 30 | 59.8 | 49.3 |

| Oct. 1 to Nov. 4 | 58.9 | 48.4 |

| Vaccination begins | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Nov. 5 to Dec. 12 | 63.6 | 56.1 |

| 2021 | ||

| Jan. to Feb. | 56.0 | 43.3 |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Mar. to Apr. | 76.9 | 50.4 |

| June to Aug. | 88.6 | 60.7 |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Sept. to mid-Nov. | 93.1 | 64.2 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||

| Mid-Nov. 2021 to Feb. 2022 | 75.2 | 58.9 |

|

... not applicable Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, Annual, 2018 and 2021. |

||

Description of Figure 3

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| average daily minutes of physical activity | ||

| Before the pandemic | ||

| 2018 | ||

| January to March | 33.7 | 28.5 |

| April to June | 35.5 | 24.7 |

| July to September | 35.4 | 26.3 |

| October to December | 31.1 | 23.0 |

| 2019 | ||

| January to December | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| January 2 to March 13 | 31.5 | 26.7 |

| 1st wave | ||

| 2020 | ||

| March 14 to August 31 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2nd wave (Beta) | ||

| 2020 | ||

| September 1 to 30 | 25.0 | 16.1 |

| October 1 to November 4 | 24.0 | 16.6 |

| Vaccination begins | ||

| 2020 | ||

| November 5 to December 12 | 21.3 | 18.7 |

| 2021 | ||

| January to February | 29.1 | 19.8 |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| March to April | 35.2 | 19.1 |

| June to August | 35.6 | 27.5 |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| September to mid-November | 34.4 | 17.8 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||

| Mid-November 2021 to February 2022 | 31.1 | 21.8 |

|

... not applicable Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2018, 2020 and 2021. |

||

Description of Figure 4

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| average daily minutes of physical activity | ||

| Before the pandemic | ||

| 2018 | ||

| Jan. to Mar. | 22.2 | 17.0 |

| Apr. to June | 24.8 | 19.4 |

| July to Sept. | 10.8 | 9.4 |

| Oct. to Dec. | 27.2 | 22.2 |

| 2019 | ||

| Jan. to Dec. | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| Jan. 2 to Mar. 13 | 23.6 | 20.2 |

| 1st wave | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Mar. 14 to Aug. 31 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2nd wave (Beta) | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Sept. 1 to 30 | 12.0 | 7.8 |

| Oct. 1 to Nov. 4 | 15.3 | 10.9 |

| Vaccination begins | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Nov. 5 to Dec. 12 | 16.2 | 15.1 |

| 2021 | ||

| Jan. to Feb. | 13.2 | 12.2 |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Mar. to Apr. | 18.6 | 8.8 |

| June to Aug. | 8.5 | 4.9 |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Sept. to mid-Nov. | 29.6 | 20.5 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||

| Mid-Nov. 2021 to Feb. 2022 | 16.7 | 14.2 |

|

... not applicable Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2018, 2020 and 2021. |

||

Description of Figure 5

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| average daily minutes of physical activity | ||

| Before the pandemic | ||

| 2018 | ||

| Jan. to Mar. | 22.2 | 22.8 |

| Apr. to June | 28.0 | 27.5 |

| July to Sept. | 27.9 | 26.0 |

| Oct. to Dec. | 25.0 | 19.0 |

| 2019 | ||

| Jan. to Dec. | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||

| Jan. 2 to Mar. 13 | 24.7 | 21.3 |

| 1st wave | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Mar. 14 to Aug. 31 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2nd wave (Beta) | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Sept. 1 to 30 | 20.6 | 22.6 |

| Oct. 1 to Nov. 4 | 17.7 | 17.0 |

| Vaccination begins | ||

| 2020 | ||

| Nov. 5 to Dec. 12 | 19.7 | 19.7 |

| 2021 | ||

| Jan. to Feb. | 12.5 | 8.7 |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Mar. to Apr. | 17.9 | 17.4 |

| June to Aug. | 32.2 | 22.1 |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||

| 2021 | ||

| Sept. to mid-Nov. | 26.4 | 22.5 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||

| Mid-Nov. 2021 to Feb. 2022 | 22.4 | 18.8 |

|

... not applicable Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2018, 2020 and 2021. |

||

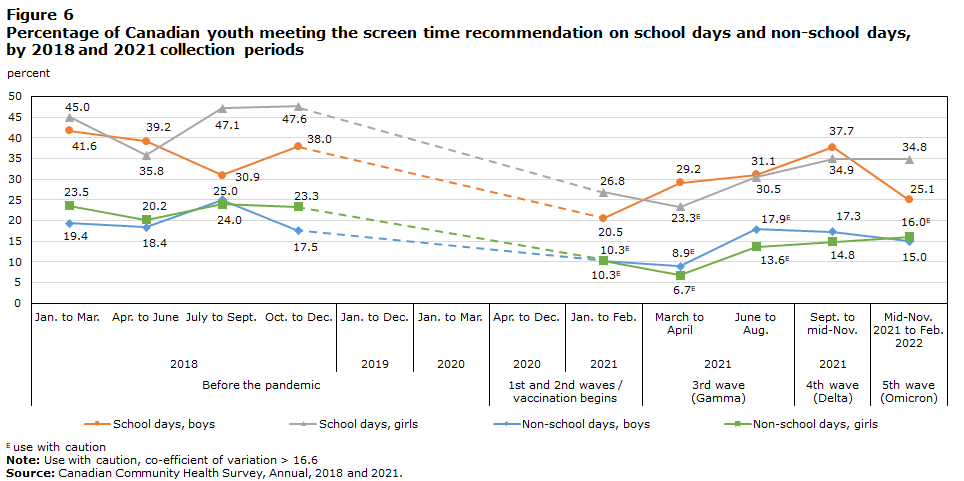

Overall, the percentage of youth meeting the screen time recommendations was lower during the pandemic (2021) than before the pandemic (2018) (Figure 6). The percentage in 2018 remained relatively stable across the year, with a notable sex difference in weekday screen time (specifically, more girls met the recommendation in 2018 compared with boys from July to December 2018). The percentage of boys meeting the screen time recommendation on school days increased from early 2021 to the fall of 2021 before dropping again at the onset of the Omicron wave. The percentage meeting the screen time recommendation on non-school days was lowest in early 2021, then remained stable for the latter half of the year.

Description of Figure 6

| School days | Non-school days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| percent | ||||

| Before the pandemic | ||||

| 2018 | ||||

| January to March | 41.6 | 45.0 | 19.4 | 23.5 |

| April to June | 39.2 | 35.8 | 18.4 | 20.2 |

| July to September | 30.9 | 47.1 | 25.0 | 24.0 |

| October to December | 38.0 | 47.6 | 17.5 | 23.3 |

| 2019 | ||||

| January to December | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2020 | ||||

| January to March | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 1st and 2nd waves / vaccination begins | ||||

| 2020 | ||||

| April to December | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2021 | ||||

| January to February | 20.5 | 26.8 | 10.3Note E: Use with caution | 10.3Note E: Use with caution |

| 3rd wave (Gamma) | ||||

| 2021 | ||||

| March to April | 29.2 | 23.3Note E: Use with caution | 8.9Note E: Use with caution | 6.7Note E: Use with caution |

| June to August | 31.1 | 30.5 | 17.9Note E: Use with caution | 13.6Note E: Use with caution |

| 4th wave (Delta) | ||||

| 2021 | ||||

| September to mid-November | 37.7 | 34.9 | 17.3 | 14.8 |

| 5th wave (Omicron) | ||||

| Mid-November 2021 to February 2022 | 25.1 | 34.8 | 15.0 | 16.0Note E: Use with caution |

|

... not applicable E use with caution Note: Use with caution, co-efficient of variation > 16.6 Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, Annual, 2018 and 2021. |

||||

Discussion

The present study leverages high-quality and large-scale population surveillance data from the CCHS to provide information about how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the physical activity and screen time habits of Canadian youth. Overall, the analysis indicates that Canadian girls became less active and were engaging in more screen time in 2021 compared with 2018. After an initial decline in physical activity in the fall of 2020, levels of physical activity among boys appear to have rebounded in 2021 to levels like those observed before the pandemic (2018). The decrease in physical activity across all domains was more pronounced among girls compared with boys. The results of this analysis suggest that from 2018 to 2021, many youth shifted from the recommended screen time category (two hours or less per day) to the highest screen time category (four hours or more per day). In addition, the percentage meeting the screen time recommendation decreased more among girls than boys. The trend analyses suggest some recovery in physical activity occurred in 2021; however, a subsequent decrease is evident in the final collection period among boys and girls (mid-November 2021 to February 2022). This period coincides with the Omicron wave, which coincided with many school closures and sports cancellations across the country.Note 13

Previous studies have reported that girls are less active compared with boys.Note 14, Note 15 Canadian Women & Sport published a report in 2022 that highlighted some concerning statistics about sports participation among Canadian girls. For example, one in five parents reported their daughters are less interested in sports now than before the pandemic, and one in three adolescent girls currently engaged in sport is unsure she will continue.Note 9 These statistics corroborate the findings of the present analysis that show a greater impact of the pandemic on physical activity among girls compared with boys. Sports participation is captured within the recreational physical activity domain and dropped by 25 minutes per week among girls and 5 minutes per week among boys. Similarly, the total physical activity drop among boys (-14.7 minutes per week) was more modest than among girls, where the drop was almost an hour per week (-58.1 minutes per week). Boys appear to have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels of recreation and overall physical activity. In contrast, the proportion of girls meeting physical activity recommendations in November 2021 to February 2022 remains lower than at any time from January 2018 to March 2020.

As COVID-19 becomes endemic, public health experts are highlighting potential areas of action to help Canadian children and youth recover their lifestyle habits to pre-pandemic levels.Note 16 The Rally Report highlights information about the self-perceived benefits (e.g., mental health and well-being) and barriers (e.g., social belonging concerns and lack of high-quality programs) to organized sports and activity participation among girls in Canada.Note 9 It will be important to continue to track national-level data from the CCHS and other data sources to determine whether the gap between boys and girls remains as the recovery from the pandemic continues. A key part of recovery appears to be supporting parents in overcoming newfound screen usage habits developed because of online learning during the pandemic and to help their children re-engage with organized sports and activities that stopped during the pandemic.Note 17, Note 18, Note 19, Note 20 Another opportunity may be diminishing the reliance on school and sport-related physical activity to meet all the activity needs of Canadian youth, by reducing barriers to active transportation wherever and whenever possible. If youth were able to walk, bike, or wheel (e.g., use scooters or inline skates) to their destinations of choice, a temporary reduction in school or sport-related physical activity may have far less impact on the proportion of youth meeting physical activity recommendations. Reducing barriers to active transportation (e.g., more and safer sidewalks and bike lanes) is also likely to benefit older and younger Canadians as well, in a way that sports and school-based physical activity do not.Note 21, Note 22

A key strength of the present analysis is the use of sub-annual CCHS collection periods to examine the within-year variation in physical activity and screen time. This is important because it allows for the effect of seasonality on physical activity to be accounted for. In the context of COVID-19, the sub-annual collection periods are useful to determine whether particular waves of the pandemic were either more or less impactful on health behaviours. The 2018 data presented herein show how physical activity varies within a typical year among Canadian youth. Among adults, physical activity tends to be higher in the warmer seasons;Note 23 however, as evidenced by the 2018 data, youth were less active during the summer. This finding has been observed before and has been attributed, in part, to the lack of structured programming that school provides.Note 24, Note 25 The physical activity data for 2020 and 2021 were more variable than that for 2018 (especially among boys) and show that some waves of the pandemic (e.g., Omicron) may have been more impactful on physical activity and screen habits than earlier waves. Taken together, the findings confirm that regular attendance at school has important benefits beyond academic outcomes.

Another strength of the present analysis is the common questionnaire module implemented in the pre-pandemic period of 2018 and the 2020 and 2021 pandemic years. The low response rates during the pandemic raise bias concerns, and results should be interpreted with caution; however, measures were taken to mitigate these issues in the weighting procedures. Despite these strengths, the data collection challenges of 2020 highlight the importance of optimizing response rates and increasing sample sizes as much as is feasible. Doing so would facilitate the completion of more robust analyses to understand how and to what extent some population groups or youth from certain regions of Canada were differentially affected by the pandemic. A limitation of the present study is reliance on self-reported physical activity and screen time information, which can be influenced by social desirability bias and recall issues. Finally, a wide range of public health restrictions in various domains (school, work, and society) were ongoing in 2020 and 2021, and they differed across regions of Canada. This regional variation in restrictions was not accounted for in the present analysis. The overall pandemic-related events (e.g., waves and vaccination timing) are noted in the sub-annual figures to provide overall context to the trend analyses.

The pandemic affected the lifestyle habits of Canadians through much of 2020 to 2022 and may continue to have impacts into 2023 and beyond. The decrease in physical activity and increase in screen time among youth from 2018 to 2021 are a concerning public health situation, given the well-established link between these behaviours and poor physical health, poor psychosocial health, and negative academic outcomes.Note 26 Will the pandemic-related decrease in sports participation lead to ongoing disengagement from organized sports and activities? The findings of the present study corroborate the Rally Report’s concerns that physical activity among girls is not rebounding as quickly as it is among boys. As the country emerges from the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022, ongoing periodic assessment of lifestyle habits among Canadians will be important. Doing so will offer some insight into who may need more support after the pandemic to readopt or improve healthy lifestyle habits.

- Date modified: