Education, learning and training: Research Paper Series

Enrolment of British Columbia high school graduates with special education needs in postsecondary education and apprenticeship programs: A case study of the class of 2009/2010

by Alana Barnett and Laura Gibson

Skip to text

Text begins

Overview

This study combines information from British Columbia administrative school data, the Postsecondary Student Information System, and the Registered Apprenticeship Information System to analyze the postsecondary and apprenticeship enrolment rates of high school graduates with and without special education needs, in the six years following graduation.

- In the 2009/2010 school year, 44,637 students aged 15 to 19 years graduated from high school in British Columbia with a Dogwood diploma. Just over 5% of these graduates had a special education need (after students with gifted status were excluded); 0.7% of graduates had a physical or sensory special education need, and 4.6% had a mental health-related or cognitive special education need. Males were overrepresented in both groups.

- More than half of graduates with physical or sensory special education needs (68.6%) and graduates with mental health-related or cognitive special education needs (65.0%) enrolled in a postsecondary program or apprenticeship in the six years following high school graduation. This compares with 80.3% of graduates without special education needs.

- Lower proportions of graduates with physical or sensory special education needs and graduates with mental health-related or cognitive special education needs in postsecondary education come from gaps in enrolment in the year immediately following graduation. Graduates with physical or sensory special education needs were as likely (22.5%) as their peers without special education needs (23.6%) to enrol in later years, and graduates with mental health-related or cognitive special education needs were more likely (27.1%) to have done so.

- Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were less likely (29.4%) than their peers without special education needs (47.4%) to enrol in an undergraduate degree program, but enrolled in college-level certificate, college-level diploma and undergraduate associate degree programs at similar rates.

- Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive special education needs were less likely than their peers without special education needs to enrol in undergraduate degree programs (15.2% compared with 47.4%) and college-level diploma programs (17.6% compared with 22.2%), but were more likely to enrol in apprenticeship programs (10.3% compared with 4.4%) and college-level certificate programs (20.5% compared with 15.4%).

For many youth, the transition out of high school and into postsecondary education marks the first major decision they make for themselves as adults: what type of program best suits their career ambitions? Which field of study most interests them? Some youth with disabilities, however, may find they participate differently in postsecondary education than their peers without disabilities. For example, in 2017, 12% of Canadians with a disability aged 15 to 24 years who were in school at the time, or had been in school within the previous five years, reported that because of their condition they began school later than most other people their age, and 29% reported that their education was interrupted for long periods of time because of their conditionNote .

In 2017, according to the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability, one in eight Canadian youthNote , aged 15 to 24 years, had a disabilityNote Note . Understanding how youth with disabilities transition from high school to postsecondary education or apprenticeship programs helps to inform policymakers of challenges that these youth face in terms of their employment and economic situations, and the various supports that they may require. For example, in 2016, Canadians aged 25 to 64 with a disability were less likely to be employed than their counterparts without disabilitiesNote and were also less likely to have a certificate, diploma or degree at the bachelor’s level or aboveNote . However, individuals with disabilities who had a postsecondary credential were more likely to be employed than their counterparts who had a high school diploma or lessNote . Previous research has shown that the relationship between educational attainment and disability is a bidirectional oneNote , meaning it is possible that these discrepancies in employment and educational attainment are due in part to lower postsecondary enrolment among people with disabilities, and in part to higher incidence of disabilities in people with certain occupations later in life. This study will help to characterize postsecondary enrolment among Canadian youth with disabilities.

During primary and secondary schooling, if a child has a disability, this is generally recorded in administrative data as the child having a special education needNote . The population of youth with disabilities and youth identified as having special education needs does not fully overlap, with some youth with disabilities not being captured as having special education needs, and some special education needs being identified that are unrelated to disability, such as having gifted status. However, the population with special education needs generally includes children with disabilities that may affect their learning in, or access to, the school environment. When broken down into smaller groups based on the type of special education need, these administrative school data can be used to provide insight into how youth with special education needs participate in postsecondary education.

For example, a 2012 studyNote showed that Grade 12 students in the Toronto District School Board with special education needs (not including gifted status)Note had lower predicted probabilities of enrolling in university compared with students who did not have special education needs (0.344 versus 0.600) after accounting for other factors such as parental education, gender, race, and academic performance, among others. This study considered enrolment within the first three years after grade 12 graduation.

The present study uses high school administrative data from the British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Education integrated with the Education and Labour Market Longitudinal Platform (ELMLP) to answer four questions: Are high school graduates with certain types of special education needs less likely to attend postsecondary educationNote than graduates without special education needs? Are graduates with certain types of special education needs more likely to delay entering postsecondary education? If so, does the gap in enrolment close over time? And finally, are graduates with certain types of special education needs more or less likely to follow certain programs of study (e.g., apprenticeships versus undergraduate degree programs) than graduates without special education needs? Although gifted statusNote is considered to be a special education need in British Columbia, graduates with gifted status are excluded from this analysis. Preliminary analysis suggested that graduates with gifted status generally have different patterns of postsecondary enrolment than graduates with other special education needs (data not shown).

The BC Ministry of Education has previously studied immediate and delayed entry into postsecondary education over longer periods of time, and found that most high school graduates (62%) enter postsecondary education within two years of graduating. However, they have not examined how this may differ for graduates with different types of special education needs, or whether graduates with special education needs are more or less likely to enrol in certain postsecondary programs than graduates without special education needs.

The present study builds on existing research in two important ways: it extends the period of study to six years after high school graduation, including more graduates that delayed their enrolment, and it includes apprenticeships as an enrolment option. Current data show that persons with a disability in Canada are as likely to have an apprenticeship or trades certificate as persons without a disabilityNote .

Data

This study uses data on high school graduates from the British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Education integrated with data from the Postsecondary Student Information System (PSIS) and the Registered Apprenticeship Information System (RAIS) within the Education and Labour Market Longitudinal Platform (ELMLP) environment for longitudinal analysis. Due to the combination with PSIS and RAIS data, as well as differences in the sample definitionNote , the estimates presented in this article will differ slightly from those previously published by the BC Ministry of Education.

The BC Ministry of Education data include information on students who previously attended or are currently attending public and independent schools in BC, including student characteristics and their progress through the education system. The ELMLP is a data environment whereby anonymized datasets can be combined longitudinally for research and statistical purposes.

PSIS is an administrative database that provides data on enrolment and graduation of Canadian public college and university students by type of program and credential, and field of study. RAIS is an administrative database of all Canadian (provincial and territorial) annual data on registered apprentices and trade qualifiers. Together, they provide a more complete picture of how high school graduates in Canada participate in postsecondary educationNote . In this study the term ‘postsecondary education’ refers to college and university programs as well as apprenticeships.

In the BC administrative dataNote , students are assigned a maximum of one special education need as part of one variableNote with multiple categories such as a learning disability, autism spectrum disorder and a physical disability. While, in reality, students may have more than one special education need, the administrative data only identify one special education need per graduate. For the purposes of this study, students were identified based on their special education need status in their final year of high school. Based on the category identified, students were divided into three groups: students with physical or sensory education needs, students with mental health-related or cognitive education needs, and students without special education needs.

The physical or sensory education needs group includes students with a physical disability or chronic health impairment, those who are deaf or hard of hearing, those with visual impairment, those who are deaf/blind and those who are physically dependentNote . The mental health-related or cognitive education needs group includes students with a learning disability, severe learning disability, mild intellectual disability, moderate to profound intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, or mental health-related illness and those needing moderate behaviour support or intensive behaviour interventions.

Methodology

This analysis examines the cohort of students who graduated from high school in British Columbia with a secondary school diploma (known in BC as a Dogwood diploma) in the 2009/2010 school year, were 15 to 19 years of age at the time of graduation, and entered postsecondary education from 2010 to 2016. Some high school students with special education needs work toward an Evergreen certificate, which recognizes the achievement of one’s personal learning goals, but it is not an equivalent to a Dogwood diploma. Among grade 12 students aged 15 to 19 years in the 2009/2010 school year, 780 students or 1.0% of all students received an Evergreen certificate. These students are excluded from this analysis.

Enrolment in postsecondary education includes graduates who enrolled either full time or part time in a postsecondary program or an apprenticeship program in Canada from 2010 to 2016, the six-year period following high school graduation. Enrolment in the first academic year following high school graduation (2010/2011) is considered to be immediate enrolment. Delayed enrolment refers to first enrolment in any of the later years.

When examining enrolment by specific educational qualification, it is possible that graduates entered more than one educational qualification within the six-year period, in which case they are counted in both. The exception to this is if a graduate entered a college or university program, in which case they would not be counted as having entered an apprenticeship program at a later date. This study excludes basic education programs, qualifying programs, pre-university programs and non-program studies from the analysis on postsecondary enrolments.

In the 2009/2010 school year, 44,637 students graduated from high school in British Columbia with a Dogwood diploma. Special education need status was derived according to the presence of a special education need, which includes gifted status, and the type of need. Overall, 1,146 graduates (2.6%) had gifted status and were excluded from further study. The majority of the remaining 43,491 graduates (94.7%) did not have a special education need (Table 1). Just over 5% of graduates had a physical or sensory education need or mental health-related or cognitive education need.

| Graduates without special education needs | Graduates with physical or sensory education needs | Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | |

| Total | 41,169 | 94.7 | 306 | 0.7 | 2,016 | 4.6 |

| Men | 20,160 | 49.0 | 189 | 61.8 | 1,338 | 66.4 |

| Women | 21,006 | 51.0 | 117 | 38.2 | 681 | 33.8 |

|

Note: Estimates are rounded to a multiple of 3. Totals may not add up due to rounding. Source: British Columbia Ministry of Education K-12 dataset 2009/2010, PSIS and RAIS longitudinal 2010 to 2016 |

||||||

Graduates without special education needs are used as a control group with whom to make comparisons for graduates with special education needs. We conducted chi-squared tests to determine whether differences between these groups were statistically significant at p<0.05. The four research questions will be addressed first for graduates with physical or sensory education needs, then for graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs.

Overall, males made up a larger share of graduates with physical or sensory education needs and mental health-related or cognitive education needs than graduates without special education needs. Among graduates without special education needs, the sex distribution was roughly equal.

Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were less likely than graduates without special education needs to enrol in postsecondary education

Four-fifths of all students who graduated from a British Columbia high school in the 2009/2010 academic year with a Dogwood diploma entered postsecondary education in Canada in the six years following their graduation (79.5%; data not shown).

A lower proportion of graduates with physical or sensory education needs enrolled in postsecondary education, compared with their peers without special education needs. Two-thirds (68.6%) of graduates with physical or sensory education needs entered postsecondary education during this period, compared with 80.3% of their counterparts without special education needs (Chart 1).

Data table for Chart 1

| Physical or sensory education needs | Without special education needs | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Within six years of graduation | 68.6 | 80.3Note * |

| Immediate | 46.1 | 56.7Note * |

| Delayed | 22.5 | 23.6 |

|

||

Previous research has shown that most graduates who enter postsecondary education do so within one year of graduating from high schoolNote ,Note . Over half of all graduates started postsecondary education in Canada in the following year (55.8%; data not shown).

Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were also significantly less likely to enter postsecondary education immediately after graduation (46.1%) than their counterparts without special education needs (56.7%). However, in later years, graduates with physical or sensory education needs entered postsecondary education at similar rates to graduates without special education needs. Breakdown of enrolment rates by sex was not possible for graduates with physical or sensory special education needs due to small sample size.

Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were less likely to enrol in undergraduate degree programs, compared with graduates without special education needs

The difference in postsecondary enrolments between graduates with physical or sensory education needs and their peers without special education needs largely comes from lower enrolment in undergraduate degree programs among those with physical or sensory education needs. Almost one-third (29.4%) of graduates with physical or sensory education needs started an undergraduate degree program within six years of graduation, compared with 47.4% of their peers without special education needs (Chart 2). Despite their lower enrolment in these programs, undergraduate degree programs were the most popular postsecondary program among graduates with physical or sensory education needs.

Data table for Chart 2

| Physical or sensory education needs | Without special education needs | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Apprenticeship | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 4.4 |

| College-level certificate | 18.6 | 15.4 |

| College-level diploma | 21.6 | 22.2 |

| Undergraduate associate degree | 10.8 | 11.8 |

| Undergraduate degree | 29.4 | 47.4Note * |

Note: The transition rate into apprenticeship programs for graduates with physical or sensory education needs has been suppressed due to small sample size. Source: British Columbia Ministry of Education K-12 dataset 2009/2010, PSIS and RAIS longitudinal 2010 to 2016. |

||

Graduates with physical or sensory education needs tended to enrol in other educational qualifications at similar rates as graduates without special education needs. For example, graduates with physical or sensory education needs were as likely as their peers without special education needs to enrol in college-level certificate programs (generally one year in length), and college-level diploma programs (generally two years or more in length). Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were also equally as likely to have enrolled in an undergraduate associate degree program as graduates without special education needs. Undergraduate associate degrees are credentials granted to students after they complete 60 transferable undergraduate credits. Generally, students choose to transfer their credits to an undergraduate degree program after completion. Among Canadian provinces and territories, this qualification is most common in British Columbia and Yukon. The transition rate into apprenticeship programs for graduates with physical or sensory education needs has been suppressed due to small sample size.

Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were less likely to enrol in postsecondary education than graduates without special education needs

Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were significantly less likely to enter postsecondary education (65.0%) than their counterparts without special education needs (80.3%) in the six-year study period (Chart 3).

Data table for Chart 3

| Mental heath-related or cognitive education needs | Without special education needs | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Within six years of graduation | 65.0 | 80.3Note * |

| Immediate | 38.1 | 56.7Note * |

| Delayed | 27.1 | 23.6Note * |

|

||

This pattern emerged immediately after graduation when a lower proportion of high school graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs entered postsecondary education during this period (38.1%) compared with graduates who did not have special education needs (56.7%). In contrast, graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were more likely to delay their entry into postsecondary education and enrol in subsequent years than their peers without special education needs.

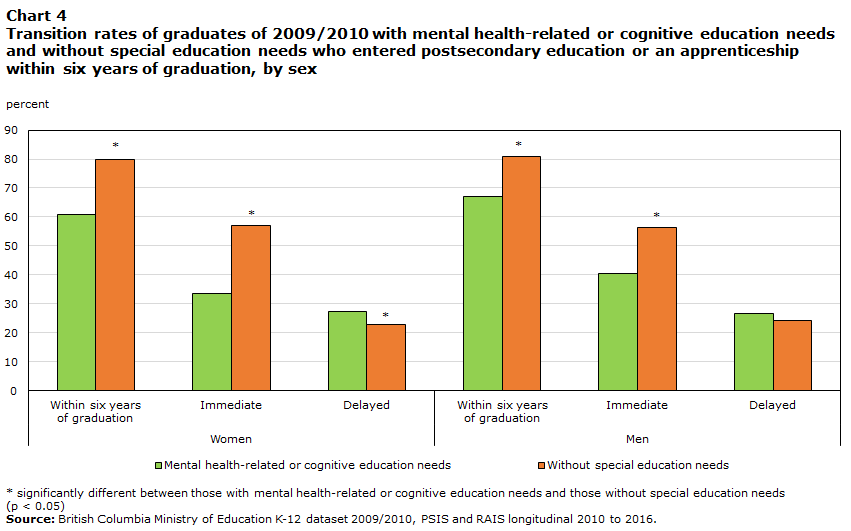

While female graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were significantly less likely to enrol in postsecondary education within one year of graduating from high school (33.5%) than their counterparts without special education needs (57.1%; Chart 4), they were four percentage points more likely to enrol in later years. In contrast, male graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs delayed their enrolment into postsecondary education at similar rates as their peers without special education needs.

Data table for Chart 4

| Mental health-related or cognitive education needs | Without special education needs | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Women | ||

| Within six years of graduation | 60.8 | 79.9Note * |

| Immediate | 33.5 | 57.1Note * |

| Delayed | 27.3 | 22.9Note * |

| Men | ||

| Within six years of graduation | 67.0 | 80.8Note * |

| Immediate | 40.4 | 56.4Note * |

| Delayed | 26.7 | 24.4 |

|

||

Young men with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were significantly more likely to enrol in a postsecondary program immediately after graduating (40.4%) than their female counterparts (33.5%; data not shown). However, a similar proportion of men and women with mental health-related or cognitive education needs delayed their enrolment in postsecondary education, and overall there was no significant difference in enrolment between sexes at the end of the six-year period for graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs.

A higher proportion of graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs entered apprenticeship programs than graduates without special education needs

Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were twice as likely as graduates without special education needs to start an apprenticeship within six years of high school graduation (Chart 5). This propensity comes primarily from male graduates. Male graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were significantly more likely (13.9%) than their male peers without special education needs to pursue an apprenticeship (7.7%; data not shown). Census data show that for men, completing an apprenticeship can be as profitable as completing a bachelor’s degree in British ColumbiaNote .

Data table for Chart 5

| Mental health-related or cognitive education needs | Without special education needs | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Apprenticeship | 10.3 | 4.4Note * |

| College-level certificate | 20.5 | 15.4Note * |

| College-level diploma | 17.6 | 22.2Note * |

| Undergraduate associate degree | 10.4 | 11.8 |

| Undergraduate degree | 15.2 | 47.4Note * |

Source: British Columbia Ministry of Education K-12 dataset 2009/2010, PSIS and RAIS longitudinal 2010 to 2016. |

||

Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were also significantly more likely to choose a college-level certificate program than their counterparts without special education needs. One-fifth (20.5%) of graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs enrolled in college-level certificate programs, compared with 15.4% of graduates without special education needs.

At the university level, graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were less likely to enrol in an undergraduate degree program than their peers without special education needs. While almost half (47.4%) of graduates without special education needs pursued an undergraduate degree, the rate was 15.2% for graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs. However, enrolment in undergraduate associate degree programs was similar for graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs and graduates without special education needs.

Conclusion

In 2009/2010, students with special education needs accounted for 5.3% of British Columbia’s high school graduating class, after excluding students with gifted status. While these graduates make up a diverse group with different skills and abilities, the majority of them pursued postsecondary education at some point in the six years following graduation.

In general, graduates with physical or sensory education needs and graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were less likely to enrol in postsecondary education, particularly undergraduate degree programs, during the study period than their peers without special education needs.

Graduates with physical or sensory education needs were less likely than their counterparts without special education needs to enter postsecondary education immediately after graduation. Enrolment in subsequent years, however, was fairly equal between the two groups.

Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were also less likely than their peers without special education needs to have enrolled in postsecondary education within six years of high school graduation. Significantly lower enrolment among graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs in the first year after graduation was the reason for this gap, as they were as likely as or more likely to enrol in later years than their peers without special education needs.

The choices of educational qualification for graduates with physical or sensory education needs were similar to graduates without special education needs, with the exception of undergraduate degree programs. A lower proportion of graduates with physical or sensory education needs enrolled in undergraduate degree programs, compared with their peers without special education needs.

There was more variation in chosen educational qualifications among graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs. College-level certificate programs were a common choice for graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs; these graduates were more likely than their peers without special education needs to have enrolled in a college-level certificate program. Graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were also more likely to have entered an apprenticeship program than their counterparts without special education needs, with young men being nearly twice as likely to do so as their counterparts without special education needs.

While graduates with physical or sensory education needs and graduates with mental health-related or cognitive education needs were less likely to enter an undergraduate degree program than graduates without special education needs, they enrolled in undergraduate associate degree programs at similar rates. Credits earned in an undergraduate associate degree program can be transferred toward an undergraduate degree upon completion.

This study examined postsecondary enrolment of high school graduates in British Columbia with and without special education needs. However, enrolment in postsecondary education is only part of the story. Further studies on this topic using the ELMLP could focus on the pathways of students with and without special education needs through postsecondary education: does having a special education need affect one’s likelihood of completing postsecondary education, or the time taken to graduate? Early career earnings of postsecondary graduates with special education needs could also be examined in future work.Note to readers:

PSIS uses academic years, while RAIS uses calendar years. This study uses data from PSIS for the 2010/2011 to 2016/2017 academic years, and data from RAIS for the 2010 to 2016 calendar years.

- Date modified: