Income Research Paper Series

A review of Canadian homelessness data, 2023

by Marc-Antoine Dionne, Christine Laporte, Jonathan Loeppky and Alexander Miller

Skip to text

Text begins

Summary

This paper reviews the various data sources available for measuring the population that is experiencing or has experienced episodes of homelessness. It focuses on data that has been collected by Statistics Canada and Infrastructure Canada and draws lessons from the Australian census to improve the data landscape in Canada. This environmental scan identifies gaps in the current data collection strategies and proposes solutions to start filling them. Working with partners, integrating data sets and strengthening the conceptual definitions could contribute to better information on homelessness in Canada and better direct supports to the homeless population.

1. Introduction

On a single day in 2018, more than 25,216 individuals across 61 communities lived in a situation of homelessness, in a shelter or not (ESDC, 2018)Note . Similarly, it is estimated that an average of 235,000 people in Canada experience one of the many types of homelessness each year (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2014). These estimates are a best guess as studying homeless remains quite difficult. The purpose of this document is to start providing solutions to this difficulty and to build on the previous work by enumerating and classifying the available data on homelessness, by identifying existing data gaps and by proposing solutions to fill those gaps.

Over the past decade, the above estimate has been frequently referenced in numerous publications regarding homelessness. The proposed figure is intended to be an aggregate of different estimates of unsheltered individuals, those sheltered and those provisionally accommodated. It calls for the use of more precise data sources.

Homelessness is defined here as, “the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it” (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2017). It encompasses several types of homelessness. Not all individuals or socio-demographic groups experience homelessness in the same way or at the same rate. The groups more likely to have an episode of homelessness are: single adult males, youth, women, indigenous people, and families. In addition to these groups, personal circumstances play a role in what lead people to become homeless. These can include family break up, family violence, loss of employment, substance use, a history of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and involvement in the child welfare system.

Four main data sources are used to measure homelessness in Canada. Each of them measures a very specific aspect of homelessness. Point-in-time enumeration is used to count the number of people experiencing homelessness on a specific day and in defined communities. The census of population, on the other hand, measures the number of people living in shelters or other collective dwellings on census day, every five years. Survey data measures past experiences of homelessness as well as present or past risks of experiencing homelessness. Finally, administrative data measures, among other things, the number of people living in shelters for victims of violence and how many interactions homeless people have with the health system.

Although several data sources exist, some challenges are inherent to the homeless population and make data collection difficult. First, homeless people rarely have a fixed address, therefore are difficult to count and are often outside the scope of surveys. This also makes them difficult to identify in administrative data. Second, stigma and prejudice towards people experiencing homelessness can hinder self-identification. Third, given the transitional nature of homelessness, it is difficult to observe/count each individual at the moment they are experiencing homelessness. Finally, while field collection can represent a solution, it often remains difficult and is limited to a few communities.

To better understand the challenges facing Canadian communities, and specifically those experiencing homelessness, robust data from different sources remains essential. Statistics Canada, as well as several partners, including Infrastructure Canada through the Homelessness Policy Directorate can take stock of the existing data in addition to identifying the gaps to be filled at this level. By using different methods and definitions, several organizations at the community, municipal, provincial and federal level, as well as at the academic level have attempted to measure and identify different facets of the homeless population.

The main objective of this document is to review the various data sources that provide information on the population that is experiencing or has experienced episodes of homelessness. It focuses on data available at Statistics Canada and Infrastructure CanadaNote where the Housing Policy Directorate is housed. It also presents the case of the Australian census, which has developed a methodology to obtain a portrait of homelessness in Australia. Specificities of each of the data sources and tables of basic descriptive statistics on respondents who have experienced homelessness in various surveys are provided.

Finally, recommendations are offered on potential data developments such as data linkage, modeling, or changes to the census. In addition, important considerations when measuring the homeless population are elaborated on.

The paper proceeds as follows, section 2 presents the conceptual aspects and definitions of homelessness. It also portrays Canadian housing needs through the introduction of the housing continuum model and briefly describes the different policies and frameworks that were established to address the different housing needs across Canada. Sections 3 and 4 describe the different data sources, surveys and administrative data hosted at Statistics Canada and Infrastructure Canada. Section 5 addresses the Australian example of estimating homelessness with Census data. Section 6 discusses the potential data development and other data development considerations.

2. Homelessness definitions and the housing continuum

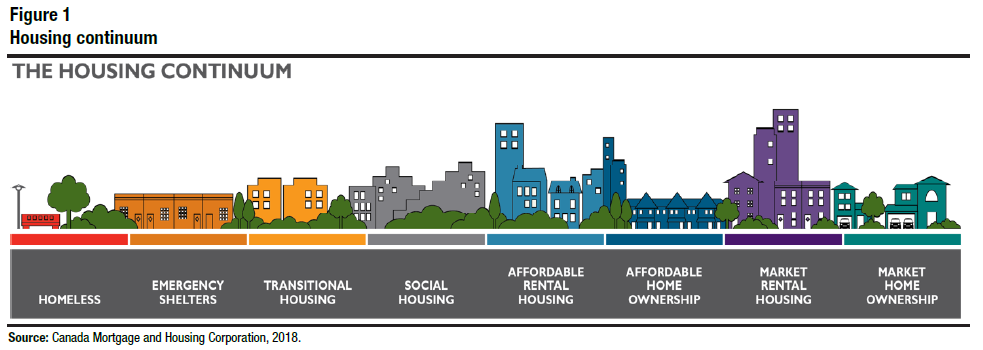

The framework used here is from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), which conceptualizes housing needs through the housing continuum model (CMHC, 2018). As shown in Figure 1, this model follows the progression of housing needs from homeless to market home ownership and identifies the different possible housing situations in-between. It intends to portray the multiplicity and fluidity of the line that can separate individuals experiencing homelessness and the rest of the population.

Description for Figure 1

The housing continuum model illustrates the variety of affordable housing types that exist in Canada that are available to individuals without the financial means to find shelter in the housing market. It progresses through 8 categories of housing need from those types that are less secure and have shorter tenures to ones that are considered more secure and have longer tenure. There are overlaps between these categories as the continuum is not necessarily linear. From left to right the 8 categories of housing are: Homeless, Emergency Shelter, Transitional Housing, Social Housing, Affordable Rental Housing, Affordable Home Ownership, Market Rental Housing, and Market Home Ownership.

The continuum starts with different types of homelessness as described above and progresses towards shelters and transitional housing geared toward the homeless population as well as different social and affordable housing programs. The continuum ends with market rental or homeownership. Throughout this paper, the focus will be on the homelessness aspects of each category, while only touching upon emergency shelters through social housing. This continuum necessitates a definition broad enough to capture the multiple different types of homelessness.

Definition of homelessnessNote

The definition by Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (2017) is widely used and defines homelessness as “the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it.” This definition is used by Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy.

Homelessness is a unique experience for everyone, taking on many forms and effecting disparate groups differently. It’s not a choice and its cause should not be perceived strictly as an issue of housing instability, but rather as a multifaceted issue that may intersect with a variety of structural, societal, and individual problems including unemployment, discrimination, domestic violence, mental health and addiction. Still, the multitude of experiences relating to an episode of homelessness can be categorized in four ways: unsheltered, emergency sheltered, provisionally accommodated, and at risk of homelessness.

Unsheltered or absolute homelessness is the type of homelessness that is generally thought of when talking about homelessness. It is a narrow concept that includes individuals that are living in public or private spaces without consent, as well as those living in places not fit for permanent human habitation (i.e. tents or shacks).

Emergency sheltered homelessness includes individuals that are currently living in shelters that are specifically designed to temporarily accommodate people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. This includes homeless shelters, shelters designed to house those fleeing domestic violence or emergency shelters for those impacted by natural disasters.

The provisionally accommodated category of homelessness includes what is commonly referred to as those experiencing hidden homelessness. It includes individuals that are living in transitional housing, individuals that were in the two previous categories, individuals without housing that are temporarily living with relatives or friends, individuals without housing living in hotels or motels, individuals that are in institutional care and lack permanent housing, and recent immigrants or refugees staying in transitional facilities.

The last category includes those at risk of being homeless or relative homelessness. This category is not in of itself considered as being homeless but must be defined to understand the cycle of homelessness. It includes individuals that are experiencing a serious imminent risk of homelessness due to unemployment, domestic violence, or a specific housing situation but are not yet considered homeless. It also includes all individuals that could be considered as precariously housed. This refers to individuals belonging to households that are in core housing need. Households that are experiencing core housing needs, as defined by the CMHC, are households that are either spending more than 30% of their before tax household income on housing (affordable), living in housing without enough bedrooms for the size and composition of the household (suitable) or living in housing that would require significant repairs (adequate).Note

In addition to the previous categories, special attention needs to be paid to the episodic nature of homelessness. Episodes of homelessness are usually characterized by individuals or families that belong to multiple categories of homelessness at some point in their lives, until they find a way to fulfill their housing needs and progress to the next step of the housing continuum.

Homelessness episodes can be classified as chronic, cyclical, or temporary depending on their duration. According to Employment and Social Development Canada’s (ESDC) Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy Directives (Infrastructure Canada, 2019), chronic homelessness episodes are defined as long term or repeated episodes of homelessness. To be considered as chronically homeless, an individual must have spent a total of at least six months (180 days) as homeless over the past year or have had recurrent episodes in the past three years with a cumulative duration of at least 18 months staying in unsheltered locations, in emergency shelters, or staying temporarily with friends or family members.

Cyclical or episodic homelessness is used to designate a type of episode where an individual is moving in and out of homelessness as a result of changes of circumstances. Such as, having been released from an institution, changes in employment status, changes in the family structure resulting from a divorce or domestic violence, losses to income or unanticipated changes to the housing situation (Echenberg and Munn-Rivard, 2020). Finally, relatively short and unrepeated episodes of homelessness such as those that could result from natural disasters, abrupt changes in housing, house fires are categorized as temporary homelessness.

A special distinction is made addressing and understanding episodes of homelessness experienced by the Indigenous communities across Canada. Thistle (2017) describes the experience of Indigenous homelessness as “…something that isn’t about being without a structure of habitation or brick and mortar home…rather, is about something much deeper: existing in the world without a meaningful sense of home or identity.” The definition used by Reaching Home captures part of this distinction in defining Indigenous homelessness as:

“Indigenous Peoples who are in the state of having no home due to colonization, trauma and/or whose social, cultural, economic, and political conditions place them in poverty. Having no home includes: those who alternate between shelter and unsheltered, living on the street, couch surfing, using emergency shelters, living in unaffordable, inadequate, substandard and unsafe accommodations or living without the security of tenure; anyone regardless of age, released from facilities (such as hospitals, mental health and addiction treatment centers, prisons, transition houses), fleeing unsafe homes as a result of abuse in all its definitions, and any youth transitioning from all forms of care” ( Infrastructure Canada, 2019).

This distinction is made to measure, understand and address the specific challenges faced by the Indigenous communities across Canada in regard to homelessness.

Start of text boxCanadian framework

The National Housing Strategy (NHS) is a Canadian affordable housing initiative. It is a $72+ billion, 10 year plan to strengthen the middle class, cut chronic homelessness in half by the 2027 to 2028 fiscal year, and stimulate the economy. It is a partnership between the federal government and the public, private and non-profit sectors to re-establish affordable housing across the country. The strategy uses a mix of funding, grants, and loans to create affordable, stable, diverse and accessible communities.

The NHS housing targets plan to remove 530,000 families from housing need, renovate 300,000 homes, and increase the housing supply by building 160,000 new homes. The NHS prioritises those in greatest housing need. This includes women and children fleeing domestic violence, seniors, Indigenous peoples, homeless people, people with disabilities, people with mental health and addiction issues, veterans, young adults, racialized groups and newcomers to Canada.

The NHS has nine shared outcomes including reducing homelessness year-over-year, increasing affordable and good condition housing, housing that promotes social and economic inclusion, improving housing outcomes year-over-year in the territories, identifying and improving the housing needs of Indigenous peoples, affordable housing that contributes to environmental sustainability, economic growth, building strong partnerships to achieve better outcomes and a more holistic response to housing issues through collaboration across the federal government.

Reaching Home is a community focused program designed to prevent and reduce homelessness through the provision of funding and support directly to relevant communities including Indigenous communities, urban centers, territorial communities, and rural and remote communities. Reaching Home supports the NHS outcomes of supporting those in great housing need, providing stable and affordable housing and cutting chronic homelessness in half.

National Housing Strategy and Infrastructure Canada - About Reaching Home: Canada's Homelessness Strategy

3. Environmental scan of Statistics Canada data sources

Due to the different types of homelessness and some of the difficulties in measuring it, there are a variety of data sources which investigates different aspects. No single survey at Statistics Canada studies all the individuals who are currently experiencing the four types of homelessness. The goal of this section is to elaborate on each of the data sources and to identify what type of homelessness is measured. Several surveys include questions regarding the experience of absolute or hidden homelessness, shelters, core housing needs and social and affordable housing. Similarly, administrative data, microdata linkages and inventory held by Statistics Canada can help provide information on homelessness and shelters across the country.

Measuring homelessness through the lens of each of the definitions mentioned in Section 2 is not an easy task. Each of the data sources described below only addresses one or two aspects of homelessness at a time. Core housing needs and social and affordable housing follow homelessness on the housing continuum and potentially include those “at risk of being homeless”.

Table 1 gives a summary of the available data, the topics covered, the year of latest release, and the frequency of collection. More specifically, Table A.1 in the Appendix lists all the questions related to homelessness in the datasets described in this section.

| Survey Name | Topics covered | Data coverage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homelessness | Shelter | Core housing needs and affordable housing | Latest year of data | Frequency | Timeframe | |

| Canadian Housing Survey (CHS) | ✓ Covered |

Not covered |

✓ Covered |

2021 | Every 2 years | Lifetime experience with homelessness |

| General Social Survey (GSS) – Canadians' Safety (Victimization) | ✓ Covered |

Not covered |

Not covered |

2019 | Every 5 years | Lifetime experience with homelessness |

| Census of Population | Not covered |

✓ Covered |

✓ Covered |

2016 | Every 5 years | Point-in-time count |

| Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA) and Transition Home Survey (THS) | Not covered |

✓ Covered |

Not covered |

2021 | Every 2 years | One-day snapshot |

| National Social and Affordable Housing Database (NSAHD) | Not covered |

Not covered |

✓ Covered |

2021 | Every year | List |

| Canada's Core Public Infrastructure Survey (CCPI) | Not covered |

Not covered |

✓ Covered |

2020 | Every 2 years | Inventory |

Canadian Housing SurveyNote

The Canadian Housing Survey (CHS) is voluntary and will be conducted every two years between 2018 and 2027 for a total of five cycles. It collects information on the various housing experiences of Canadian households such as housing needs, dwelling and neighbourhood satisfaction, housing moves including forced moves (evictions), social and affordable housing and experience of homelessness. Information is also collected on self-assessed health, various dimensions of physical and mental well-being, and various socio-demographic characteristics.

The sampling unit of the CHS is the dwelling. One survey questionnaire is completed per dwelling by the respondent (reference person) who was responsible for housing decisions.

The CHS provides information at the household level. For every household member, information on age, sex, gender, language, ethnocultural characteristics, marital status, education, current employment and veteran status of those over the age of 15 years is collected.

For a subset of variables, information is collected at the individual level.Note Those variables include information about the individual’s dwelling and neighbourhood satisfaction, their perception of economic hardship resulting from housing costs, their perceptions of neighbourhood issues and safety, as well as information on their housing life course which includes their previous accommodation and their intention to move.

CHS is used to assess core housing need across Canada. It also provides detailed statistics on households in the Social and Affordable Housing (SAH) program and its waitlist by oversampling those households.

CHS is collected in all ten provinces and three territories in 2018.Note Residents of institutions, members of the Canadian Forces living in military camps and people living in First Nations communities are excluded from the population (about 2% of the population in the provinces). People living in collective dwellings are also excluded from the survey. This includes people living in residences for dependent seniors, people permanently in school residences, work camps, etc., and members of religious and other communal colonies. People living in these collective dwellings make up less than 0.5% of the total population. However, they are included in the population estimates used in CHS estimate adjustments.

Data for the 2018 cycle was collected in 2018 and early 2019 for the CHS provincial component and in 2019 for the NWT’s Community survey. It covered 65,377 households. The most recent release CHS was cycle 2021, released in summer 2022 and covered the impacts of COVID-19 on some aspects of housing. The homeless module expanded to include reasons for housing loss and a separate module will be included for forced moves (evictions).

Measurements of homelessness and hidden homelessness

Information on previous experiences with homelessness and hidden homelessness is collected from the CHS at the individual level for the reference person in the household. Six questions regarding previous experiences with homelessness are asked to the reference person.Note Following the question, “Have you ever been homeless, that is, having to live in a homeless shelter, on the street or in parks, in a makeshift shelter or in an abandoned building?”, if answered affirmatively follow-up questions are asked; provide the duration of their longest episode and the length and year of their most recent episode.

The reference person also answers the question, “Have you ever had to temporarily live with family or friends, or anywhere else because you had nowhere else to live?”, which explores their experience with hidden homelessness. Those who reported that they had to live with friends or family are then prompted to specify the duration of that episode.

Information provided in the CHS on homelessness and hidden homelessness allows for an overview of people who have experienced homelessness but have broken that spell of homelessness and are now in private dwellings. It allows correlation between past homelessness experience and their current situation regarding housing, access to property, housing conditions, neighbourhood satisfaction, etc. (Randle, Hu and Thurston, 2021).

The survey coverage of the CHS also allows for an interesting level of data disaggregation. The CHS includes information on many of the usual socio-economic factors such as age, gender, marital status and level of education. The CHS also collects data on mental and physical health, financial difficulties, life satisfaction, Indigenous identity, sexual orientation, visible minority group, veteran status, and immigrant status (Uppal, 2022). Table 2 shows the distribution of population with homelessness experience both unsheltered and hidden for selected socio-demographic characteristics. While the sample size for this table is sufficient, the low number of homeless in Canada means that there are limitations to statistics at smaller geographic levels and with certain combinations of socio-demographic categories.

| HomelessnessTable 2 Note 1 | Hidden HomelessnessTable 2 Note 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | |

| percent | ||||

| Total | ||||

| No | 97.4 | 97.3 | 85.3 | 89.1 |

| Yes | 2.5 | 2.2 | 14.5 | 10.5 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men+ | 54.0 | 52.0 | 49.0 | 48.0 |

| Women+ | 46.0 | 48.0 | 51.0 | 52.0 |

| Age groupsTable 2 Note 3 | ||||

| 15 to 34 years old | 17.4 | 13.2 | 24.0 | 23.0 |

| 35 to 44 years old | 22.0 | 19.6 | 22.0 | 25.0 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 21.0 | 26.0 | 20.0 | 18.6 |

| 55 to 64 years old | 27.0 | 24.0 | 19.0 | 19.1 |

| 65 years old and older | 13.2 | 16.6 | 15.0 | 14.1 |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Atlantic | 5.9 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.3 |

| Québec | 9.7 | 11.8 | 18.8 | 16.9 |

| Ontario | 41.0 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 38.0 |

| Prairies | 21.0 | 19.2 | 19.1 | 19.6 |

| British Columbia | 21.0 | 23.0 | 16.4 | 17.7 |

| TerritoriesTable 2 Note 4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Housing Survey, 2018 and 2021. |

||||

Statistics on homelessness and hidden homelessness measured in the CHS are collected for the reference person of the household, or more specifically, for the individual that makes housing decisions in the household. Information is not provided for the other members of the household. Measuring only the experience of the reference person may underestimate the experience of other groups that are usually making decisions in the household, for example teenagers or adult children. Additionally, people who are/were chronically homeless may not be well represented given the bias towards people who are no longer homeless.

Also, the CHS cannot be used as a tool to enumerate the number of persons “currently” experiencing homelessness because people living in shelters, in institutions or are on the streets are not in the covered population. Moreover, factors and individual characteristics at the time of the homelessness experience are not measured. For example, the CHS does not include information on how many spells of homelessness occurred, where they occurred, and what the family’s employment or earnings characteristics were at the time of the homeless episode.

General Social SurveyNote

The General Social Survey (GSS) is a voluntary cross-sectional survey designed to gather data on social trends to monitor changes in the living conditions and well-being of Canadians. It collects information on specific social policy issues, as well as a multitude of other socio-demographic characteristics including health, habits, education, identity, housing and family composition. Every GSS focuses on a specific theme recurring every five to seven years. Recent themes include life at work and home; families; caregiving and care receiving; giving, volunteering, and participating; victimization; social identity; and time use.

The GSS collects information on persons aged 15 and over, across the Canadian provinces and territories, excluding full-time residents of institutions. The 2014 (Cycle 28) and 2019 (Cycle 34) GSS are both about Canadian’s safety and security and explore the national experience with crime and violence and their impact on daily life. These two waves of GSS include information related to homelessness issues.

More generally, the GSS includes numerous information on other habits, experiences with violence and substance abuse that provide an insight on the individuals that have experienced homelessness. In total, the 2014 GSS had a sample size of 33,120 observations. The 2019 GSS had a sample size of 22,410 observations.

Measurements of homelessness and hidden homelessness

The 2014 and 2019 GSS provide information about individuals that have experienced episodes of homelessness. All survey respondents are asked the questionNote , “Have you ever been homeless; that is, having to live in a shelter, on the street, or in an abandoned building?” Those who reported an experience with homelessness are then prompted to specify the longest period of time they were in that situation.

All respondents are also surveyed on their experience with hidden homelessness with the question: “Have you ever had to temporarily live with family or friends, in your car or anywhere else because you had nowhere else to live?” Those who reported an experience with hidden homelessness are then prompted to specify the longest period of time they were in that situation.

In 2019, an additional question was included to specify if the episode of homelessness they experienced was the result of familial violence or not.

Similar to the CHS, the GSS provides an overview of Canadians who have experienced homelessness and hidden homelessness in the past but have broken that spell and are living in a private dwelling. Correlations with the respondent's situation at the time of the survey, given that they have experienced episodes of homelessness in the past are possible. The GSS provides multiple characteristics including socio-demographic characteristics, experience of victimization, childhood abuse, disabilities and mental health, social environment and substance use. It is important to note that the sample size decreases according to the different type of homelessness.

Table 3 gives an overview of the distribution of the population with homelessness experience by selected socio-demographic characteristics. The number of observations for each type of homelessness is also included. Significant differences can be observed in the rates of individuals that have previously experienced homelessness and hidden homelessness between the GSS and the CHS even though the two surveys ask similar questions because of different target populations. The CHS notably only asks the individuals in charge of the housing decisions in the household, whereas the GSS asks every Canadian aged 15 and over not residing in institutions.

| HomelessnessTable 3 Note 1 | Hidden homelessnessTable 3 Note 2 | Hidden homelessness due to domestic violenceTable 3 Note 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2019 | 2014 | 2019 | 2014 | 2019 | |

| percent | ||||||

| TotalTable 3 Note 4 | ||||||

| No | 98.3 | 98.3 | 92.0 | 91.2 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 66.1 |

| Yes | 1.7 | 1.7 | 8.0 | 8.8 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 33.9 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 56.9 | 50.0 | 52.6 | 50.1 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 31.1 |

| Women | 43.1 | 50.0 | 47.4 | 49.9 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 68.9 |

| Age groupsTable 3 Note 5 | ||||||

| 15 to 34 years old | 28.1 | 26.9 | 31.6 | 32.4 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| 35 to 44 years old | 21.3 | 17.7 | 21.6 | 21.9 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| 45 to 54 years old | 26.2 | 20.3 | 21.4 | 15.3 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| 55 to 64 years old | 13.7 | 19.1 | 16.4 | 16.0 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| 65 years old and older | 10.7 | 16.1 | 9.0 | 14.3 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Atlantic | 6.1 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 7.8 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Québec | 13.0 | 13.8 | 20.7 | 19.7 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Ontario | 46.8 | 38.3 | 38.1 | 35.3 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Prairies | 18.7 | 24.3 | 21.2 | 20.7 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| British Columbia | 15.4 | 15.7 | 13.0 | 15.7 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Territories | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 1.5 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | 0.7 | note: ..not available for a specific reference period | note: x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act Note: While the sample size for this table is sufficient, the low number of homeless in Canada means that there are limitations to statistics at smaller geographic levels and certain combinations of socio-demographic categories. Sources: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2014 and 2019. |

||||||

The GSS also provides information on the duration of the longest episode of homelessness. However, it lacks details about the spell of homelessness, such as when it occurred, how long it lasted, how many spells were there, where it occurred. Moreover, it does not provide information about individual or family characteristics at the time of any of their episodes. While correlations can be established between individual characteristics and the likelihood of homelessness episodes (Rodrigue, 2016), it is impossible to determine with certainty which event came first. For example, while an individual may report a history of victimization and homelessness, it is impossible to know which of these two events came first.

Finally, because respondents surveyed are no longer homeless or are out of a homelessness spell, those who are chronically homeless or still in a homelessness episode may not be represented.

Census of population

The census offers a portrait of Canadians and their place of residence every five years. As place of residence, the census includes two broad types of dwellings: private or collective. The collective dwellings refer to a dwelling of a commercial, institutional or communal nature.Note They are classified into 10 categories including hospital, nursing homes and/ or residence for senior citizens, correctional facilities, religious establishments and shelters. In 2021, approximately 657,920 Canadians were living in a collective dwelling.Note

Shelters are divided in three categories: (1) shelters for persons without a fixed address (homeless shelters); (2) shelters for abused women and children and transition homes; and (3) other shelters and transition homes. The 2021 Census enumerated people who spent the night of May 11th to May 12th in shelters or similar facilities by using administrative records or census questionnaires with the assistance of administrators. More than 15,185 Canadians were living in shelters on that night.Note About 70% of these shelter residents were enumerated in homeless shelters, which represents an important part of the absolute homeless population.

The census is one of the sources used to assess the core housing need indicator in Canada, along with the CHS. Core housing need is one of the main indicators of an individual being “at risk of homelessness.” A household is defined as being in core housing need if it fails to meet three housing standards: (1) adequate housing is met if the resident does not report their dwelling as in need of any major repairs; (2) suitability is met if the dwelling has enough bedroom for the size of the resident household according to the National Occupancy Standard; and (3) affordability, which accounts for the majority of households reporting as being in core housing need, is met if the household’s shelter cost is under 30% of their total before-tax income. A distinction is made if the same household were able to pay the median rent of an alternative suitable local dwelling than they are not considered to be in core housing need.Note

Measurement of shelter population

The census is not an adequate tool to frequently enumerate the homeless population. However, the census enumerates the homeless population in shelters across the country in real time on Census night, with limited socio-demographic variables.Note It is also possible to link census data from shelters to tax or administrative data to obtain a larger perspective than what is measured in the census. In the following subsections, some microdata linkages using shelter data from the census will be explored.

| Canada | Atlantic region | Quebec | Ontario | Prairies | British Columbia | Territories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| counts | |||||||

| Both Genders | |||||||

| Total | 9,275 | 225 | 780 | 4,060 | 1455 | 2,595 | 165 |

| Aged 0 to 14 years | 550 | 5 | 70 | 315 | 80 | 85 | 0 |

| Aged 15 to 19 years | 1,060 | 30 | 50 | 740 | 135 | 75 | 35 |

| Aged 20 to 24 years | 895 | 25 | 75 | 530 | 55 | 175 | 40 |

| Aged 25 to 29 years | 680 | 15 | 55 | 280 | 80 | 235 | 10 |

| Aged 30 to 34 years | 770 | 15 | 55 | 280 | 120 | 285 | 10 |

| Aged 35 to 39 years | 860 | 20 | 65 | 230 | 145 | 390 | 5 |

| Aged 40 to 44 years | 805 | 20 | 65 | 295 | 135 | 285 | 5 |

| Aged 45 to 49 years | 675 | 20 | 70 | 280 | 105 | 190 | 5 |

| Aged 50 to 54 years | 710 | 15 | 60 | 270 | 115 | 245 | 5 |

| Aged 55 to 59 years | 775 | 20 | 80 | 285 | 130 | 250 | 10 |

| Aged 60 to 64 years | 785 | 15 | 55 | 275 | 190 | 230 | 20 |

| Aged 65 years and over | 720 | 15 | 85 | 290 | 160 | 155 | 10 |

| Men+ | |||||||

| Total | 5,450 | 140 | 505 | 1,940 | 1,025 | 1,725 | 110 |

| Aged 0 to 14 years | 370 | 5 | 25 | 205 | 60 | 75 | 0 |

| Aged 15 to 19 years | 455 | 15 | 15 | 300 | 95 | 15 | 15 |

| Aged 20 to 24 years | 465 | 20 | 35 | 260 | 45 | 85 | 20 |

| Aged 25 to 29 years | 410 | 10 | 45 | 135 | 35 | 175 | 10 |

| Aged 30 to 34 years | 355 | 5 | 25 | 80 | 75 | 165 | 10 |

| Aged 35 to 39 years | 520 | 15 | 45 | 110 | 100 | 250 | 10 |

| Aged 40 to 44 years | 545 | 15 | 45 | 185 | 80 | 205 | 10 |

| Aged 45 to 49 years | 355 | 10 | 55 | 105 | 80 | 100 | 5 |

| Aged 50 to 54 years | 435 | 10 | 55 | 135 | 95 | 135 | 5 |

| Aged 55 to 59 years | 515 | 15 | 45 | 140 | 90 | 210 | 10 |

| Aged 60 to 64 years | 580 | 10 | 55 | 155 | 160 | 180 | 20 |

| Aged 65 years and over | 450 | 10 | 60 | 135 | 110 | 130 | 10 |

| Women+ | |||||||

| Total | 3,820 | 80 | 275 | 2,120 | 425 | 870 | 50 |

| Aged 0 to 14 years | 180 | 5 | 40 | 110 | 20 | 5 | 0 |

| Aged 15 to 19 years | 600 | 10 | 35 | 440 | 40 | 60 | 20 |

| Aged 20 to 24 years | 435 | 5 | 40 | 265 | 10 | 90 | 20 |

| Aged 25 to 29 years | 270 | 5 | 10 | 140 | 50 | 60 | 0 |

| Aged 30 to 34 years | 415 | 10 | 35 | 200 | 50 | 125 | 0 |

| Aged 35 to 39 years | 340 | 5 | 25 | 120 | 50 | 140 | 0 |

| Aged 40 to 44 years | 260 | 5 | 15 | 105 | 50 | 75 | 0 |

| Aged 45 to 49 years | 320 | 10 | 15 | 180 | 25 | 85 | 0 |

| Aged 50 to 54 years | 270 | 0 | 0 | 135 | 15 | 110 | 0 |

| Aged 55 to 59 years | 260 | 5 | 30 | 145 | 35 | 45 | 0 |

| Aged 60 to 64 years | 205 | 5 | 5 | 120 | 25 | 50 | 0 |

| Aged 65 years and over | 265 | 10 | 25 | 155 | 50 | 30 | 0 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2021. | |||||||

The census is an enumeration on one specific day every five years, as a result will not measure those who were in shelters at other times of that year and does not represent the total number of homeless people. Some people might be enumerated in other places of residence such as other types of collective dwellings, for example in hospitals, or in private dwellings with friends and families in the case of hidden homelessness. It is important to note that not all homeless people live in shelters and similarly not all people living in shelters are necessarily homeless.

Finally, additional details about shelter residents such as income, are obtained through linking tax and census data. However, McDermott, Harding and Randle (2019) raised concerns about the high imputation rates among usual residents of shelters and the possible impact it might have on the quality of certain variables.

Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of AbuseNote

The Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA), previously The Transition Home Survey, is conducted every two years and provides a portrait of the residential facilities across Canada whose specific mission is to provide lodging for those that have experienced domestic violence. It enumerates the capacity of facilities (short-term or long-term shelters for victims of abuse, transition homes, interim housing and safe home networks) that have been providing services in the last year and conducts a Point-in-Time (PiT) count of the residents of those facilities.

The survey contains socio-demographic information on the residents such as their type of admission, age, geographic location, type of abuse endured, service provided by the shelter, visible minority and indigenous identity status and if the person is accompanying a minor. The latest data was collected from April 12th to August 31st, 2021, and was released on April 12th, 2022.

Measurements of homelessness and hidden homelessness related to domestic violence

The availability of information on gender, whether the individual is accompanied by a minor and their parental status offers an opportunity to measure homelessness and hidden homelessness experiences of women and how violence affects this group. Variables regarding the service and number of beds available in these types of shelters provide an insight on the service specifically available for this population and how the supply of available beds has evolved over time. This dataset contains a lot of socio-demographic information on the specific population of abuse shelter residents. It has been used to provide a portrait of indigenous victims of abuse across Canada (Maxwell, 2020).

National Social and Affordable Housing Database

The National Social and Affordable Housing Database (NSAHD) is a list of social and affordable dwellings and housing units across the country maintained by Statistics Canada. More concretely, it is a subgroup of the Statistics Canada address database that lists the dwellings that are dedicated in whole or partially to affordable housing. This subgroup is identified by matching addresses found in administrative data from several CMHC and several provincial/territorial housing authority sources.

The NSAHD includes information such as funding programs, the number of units, the construction period, the end date of an agreement, etc. However, information might not be available in all provinces.

The database does not include information on residents. However, a current project links NSAHD information with T1 Family File (T1FF) and 2016 Census data (linkage number #036-2018) to produce resident profiles related to these SAH units.Note The linkage of provincial and territorial, social and affordable housing administrative data to T1FF and Census of population data project will be used by Statistics Canada for the production of annual custom tables to data providers of social and affordable housing programs and to the CMHC. The linkage will inform the data providers on additional topics such as demographics, income and characteristics of the dwellings of those living in social and affordable housing.

This dataset can be used to portray a larger variety of social and affordable housing and offer a linkage occasion that other inventory of public housing databases such as Canada’s Core Public Infrastructure Survey might not offer.

Canada's Core Public Infrastructure SurveyNote

Canada’s Core Public Infrastructure Survey (CCPI), conducted every two years, collects statistical information on the inventory, condition, performance, and asset management strategies of core public infrastructure assets owned or leased by different levels of the Government of Canada. This includes bridge and tunnel assets; culture, recreation, and sports facilities; potable water assets; public transit assets; road assets; public social and affordable housing assets; solid waste assets; storm water assets; and wastewater assets but, notably, not shelters.

The information collected is used by the public service to better understand the current condition of Canadian public infrastructure. The target population of this survey consists of local, municipal, regional, provincial, and territorial governments that own one or more core public infrastructure asset. The latest data was collected from October 13th to December 22nd, 2021.

This dataset provides a portrait of publicly owned social and affordable housing assetsNote available to the different levels of government to help and assist those that experience episodes of homelessness. The data provides a level of geographical disaggregation that allows users to easily assess infrastructure and evaluate the supply of affordable housing available in each community. Specifically, it can be used to assess the affordable housing available to an Indigenous community or an underserved rural community. The dataset also provides insights on the availability of other infrastructure, like public transit, near affordable housing and that infrastructure expected useful life. This data is an inventory and in so, does not provide insight on whether the asset is currently in use or not.

4. Other sources of data related to homelessness

Outside Statistics Canada, other projects have been put in place to address questions related to homelessness. The National Homelessness Information System (NHIS)Note is a data monitoring initiative maintained by Infrastructure Canada, formerly maintained by ESDC. The Homeless Individual and Families Information System (HIFIS) is the data management system associated with this initiative. HIFIS allows communities to collect and track information about the people accessing homelessness sector resources in a community-wide coordinated access system. It is a centralized data management system to measure and keep track of all the data gathered by the different initiatives to measure homelessness led by the NHIS and presents interesting development opportunity regarding collaboration with other governmental initiatives. Statistics Canada publishes data from HIFISNote on the capacity, bed and shelter counts for different types of shelters in Canada.

The HIFIS notably includes the Point-in-Time (PiT) count on homelessness enumeration initiative, the Shelter Capacity Report (SCR) and the National Shelter Study (NSS).

Point-in-time countNote

The Point-in-Time (PiT) count is conducted every two years and is considered the benchmark enumeration method to identify individuals who are experiencing homelessness on a single night. Between March and April 2018, a PiT count surveyed the homelessness in 61 participating communities. More than 32,000 individuals were identified as experiencing homelessness or residing in transitional housing. PiT counts were postponed during the pandemic, while some communities were able to conduct counts before COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, others will complete them in 2023. This number includes people experiencing chronic and episodic homelessness in unsheltered locations, shelters, transitional housing, staying with others, hotels and motels, health and correctional systems and unknown locations.

The PiT count combines administrative data on shelters and transitional housings with a survey of people observed living on the street. The survey portion is comprised of 14 standardized questions on the different socio-demographic characteristics and service needs of the individual such as immigration status, indigenous identity, gender and reason for housing instability.

Some caveats regarding the PiT count are its limited geographic coverage and its concern for privacy. First, it only provides an estimate of the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in a few designated communities. Seasonal variation and migration between communities mean the PiT count cannot be used to assess cyclical or hidden homelessness. Secondly, the PiT count does not collect identifying information on individuals reported in shelters, which prevents this dataset from being linked to administrative data. However, some information on shelter residents available in the PiT count is linked from other sources (HIFIS for example) when possible.

National Service Provider ListNote

The National Service Provider List (NSPL) is an annually produced list of the different emergency and transition shelters, and their respective capacity across the country. It collects information by province and city on the shelter, the target clientele, the gender served by the shelter, and the number of beds available in the shelter.

A microdata linkageNote was recently performed between the NSPL and Statistics Canada's Linkable File Environment (LFE) to produce tables and profiles on financial and other characteristics of homeless shelters in Canada.

Shelter Capacity ReportNote and National Shelter StudyNote

The Shelter Capacity Report (SCR) is published annually and gathers information on the capacity and characteristics of all emergency homeless shelters including transitional housing and violence against women shelters across the country. The report is prepared using information from the NSPL maintained by Infrastructure Canada. The SCR inventories the number of beds available and the shelter services available to different at-risk groups on a given night in each of the different shelter types.

The National Shelter Study (NSS) is a comprehensive ongoing national-level study of homelessness across Canada. This study is based on data from about 2.5 million shelter stays in 200 of the 401 emergency shelters across Canada from 2005 to 2016. Shelters provide information on stays in their establishment to Infrastructure Canada through the HIFIS and through data sharing agreements with the different regional and municipal housing entities. The NSS provides a portrait of individuals that use emergency shelters on a typical night. It includes the occupancy rates of shelters across the country as well as the length of those stays. This provides a unique hindsight on the demand for emergency shelter services in the different communities across Canada and is used to guide different initiatives in reducing homelessness.

Alternative data sources: National Ambulatory Care Reporting System metadata

An alternative source of data to assess the number of individual experiencing homelessness across Canada, Strobel et al. (2021) used data maintained by the ICES. An Ontarian non-profit that compiled without consent, the hospital’s emergency department visits in Ontario collected in the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACR) and linked them with the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) Registered Persons Database (RPDB). The goal was to examine individuals that experiencing homelessness who visited emergency departments between 2010 and 2017.

The RPDB includes individuals that are covered by OHIP and captures socio-demographic characteristics, notably their address, if they are residents of shelters or if they are reported as experiencing homelessness. During each visit, when the personnel process a new patient, they will register the visit in the NACR and specify the date of admission, their living and housing condition, their gender and age. This information can also be used to assess trends and enumerate the characteristics of those that report experiencing homelessness for the public decision maker to evaluate their public policies (Strobel et al., 2021). Administrative health data are, however, less effective and reliable when portraying hidden homelessness or individuals that are precariously housed (Richard et al., 2019).

Despite the numerous data sources available to study homelessness, it is clear there is still work to be done to develop a harmonized methodology. One country which has a more holistic approach to the study of homelessness is Australia. The next section will compare Australia’s approach to Canada’s approach and start to draw lessons that may help Canada in the final section providing next steps.

Alternative data sources: Survey of Safety in Public and Private Space

There are also datasets which have direct relevance to homelessness but do not explicitly report on homelessness itself. An example of this is the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Space (SSPPS) which collects information on Canadians experience with safety in public and private spaces. This includes at home, in the workplace and in public spaces. It is collected every 5 years. Numerous levels of governments, academics and not-for-profits use this survey to investigate gender-based violence in Canada and this could help with policy development surrounding homelessness.

5. An international experience: Australia Census Data

Australia’s treatment of homelessness is an example that Canada could learn from. The Australian Census of Population and Housing is an international example of a country collecting information on homelessness in their census. Their census is conducted every five years and provides an overview of where and how Australian people live. To maximize the quality of their enumeration, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses a special strategy to enumerate some homeless populations that are difficult to enumerate through standard procedures. Whereas homelessness itself is not a characteristic that is directly collected in the census, estimates can be derived based on observed characteristics and assumptions about how people respond to census questions.

The ABS (2012a) definition of homelessness

The ABS defines homelessness as the lack of at least one of the following: a sense of security, stability, privacy, safety, and the ability to control living. Homelessness, therefore, may include those who have a roof over their head, but lack one of the previous elements that represents a home. The ABS statistical definition of homelessness is when a person’s current living arrangement is an inadequate dwelling, has limited or no tenure; or does not allow them to have control of, and access to space for social relations. People who lack one or more of these elements are to be defined as homeless. However, people who lack one or more of these elements are not necessarily classified as homeless if they have access to accommodation alternatives.

The ABS has developed six homeless operational groups for presenting estimates of homelessness. These groups are:

- Persons living in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out;

- Persons in supported accommodation for the homeless;

- Persons staying temporarily with other households;

- Persons living in boarding houses;

- Persons in other temporary lodgings; and

- Persons living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings.

These groups reflect the intent and design of the census variables and fall in line with the ABS definition of homelessness. People at the statistical boundary of homelessness are also of interest and can be used to assist policy and prevention services. This includes ‘Persons living in other crowded dwellings’, ‘Persons living in other improvised dwellings’ and ‘Persons marginally housed in caravan parks’.

Avoiding misclassification of homelessness and methodology

The six operational groups are used in the estimation of Australia’s homeless population. Each group has its own set of rules applied to it to assess accommodation alternatives and avoid misclassifying census respondents. For example, the group ‘living in an improvised dwelling, tent, or sleeping out’ may include construction workers whose primary residence are considered to be an improvised dwelling but are not homeless. The ABS looks at everyone who was enumerated in that group and who reported either being at home on census night or having no usual address. They then apply rules that take into consideration tenure, rent and mortgage payments and labour force status. Applying these rules eliminates mobile construction workers and others who should not be classified as homeless. People are assumed to be homeless if these items are ‘not stated’.

For the group ‘living in supported accommodation for the homeless’, the ABS looks at all persons enumerated in dwellings identified as non-private dwellings and classified as ‘hostels for the homeless, night shelter, refuge’ by owners/managers, where the respondent reported their residential status as ‘guest, patient, inmate, other resident’ or not stated. The ABS then includes dwellings flagged as being supported accommodation for the homeless, and removes overseas visitors and ‘owner, proprietor, staff, and family’ enumerated in supported accommodation.

The ABS estimates the homeless population in the group ‘Persons staying temporarily with other households’ by analyzing persons living in private dwellings (except an improvised dwelling, tent, or sleeping out) and who reported having no usual address. This group contains a large range of visitors on census night, including ‘couch surfers’. The ABS then applies rules to determine who were most likely to be homeless on census night. They exclude families moving to new locations for work, people returning to Australia or moving to the country for the first time, and those who have/will not be living in their current property for half a year or more on census year. Other visitors who are likely to have accommodation alternatives include travellers and ‘grey nomads’ (groups of people who are of retirement age touring around Australia together). The ABS identifies that homeless youth, people fleeing domestic violence, and Indigenous peoples (Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders) are likely to be underestimated in this group.

The next group ‘Persons in boarding houses’ includes persons enumerated in non-private dwellings classified as boarding houses or private hotels. Rules are applied to identify housing that was not classified as boarding housing but, on balance, the characteristics of the people living there suggest they are likely to be boarding houses. The rules applied to determine homelessness include variables for labour force participation, student status, income, tenure type, need for assistance for core activities, religion, and volunteering. The rules exclude student halls that serve multiple schools in the region and ensure retirement villages, nursing homes, homes for people with disabilities, convents/monasteries and other religious institutions are not incorrectly reclassified as homeless boarding homes.

The operational group ‘Persons staying in other temporary lodging’ includes those who reported having no usual address and were living in the non-private dwellings category ‘hotel, motel, bed and breakfast’. Rules are then applied to this group to determine who, on balance, are likely to be homeless. The rules include variables for a weekly income cut off, labour force participation, student status, persons who reported being ‘owner, proprietor, staff, and family’, and overseas visitors.

The last group ‘Persons living in severely crowded dwellings’ is operationalized as those who were enumerated as a usual resident in a private dwelling and the dwelling requires at least four or more bedrooms to accommodate everyone in the household. The ABS accesses overcrowding through the Canadian National Occupancy Standard. Overcrowding is based on the number of bedrooms in a dwelling as well as demographic characteristics including the number of usual residents, their relationship to one another, their age and their sex. Lack of alternative accommodations is assumed as people with other accommodations are not likely to stay in a severely overcrowded household. The ABS then removes all people who have been identified as homeless in the other groups. The ABS assumes that there will be underestimation in this group due to missing information on the households and usual residents not being recorded due to the fear that there are too many residents living in the household than allowed on their lease.

Published results on estimated homeless population

The ABS published an article on homelessness statistics: estimates of persons who were homeless or marginally housed, calculated from the census of population and housing. ABS finds that of the 23.4 million people living in Australia, just over 116,000 were classified as being homeless on census night (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017, 2018). Table 5 breaks down this estimate by census operational group. The largest increase in homelessness between 2011 and 2016 comes from persons living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings, an increase from 41,370 in 2011 to 51,088 in 2016. People who were born overseas and arrived in Australia in the last 5 years account for 15% of all persons who were homeless on census night 2016. The rate of homelessness for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population was 361 for every 10,000 persons. The male homelessness rate increased to 58 males per 10,000 males enumerated, up from 54 in 2011, whereas the rate for females is steady at 41 per 10,000 females.

| Operational Group | Counts |

|---|---|

| Persons living in improvised dwellings, tents, or sleeping out | 8,200 |

| Persons in supported accommodation for the homeless | 21,235 |

| Persons staying temporarily with other households | 17,725 |

| Persons living in boarding houses | 17,503 |

| Persons living in other temporary lodges | 678 |

| Persons living in severely crowded dwellings | 51,088 |

| Total estimated homeless population | 116,427 |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing, 2016. | |

Underestimated groups in homelessness estimates

The ABS (2018) recognizes that there are a few groups for which census variables provide limited opportunity to estimate those likely to be homeless. They identify three key groups, including youth, homeless people displaced due to domestic violence, and homeless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Youth homelessness (sometimes referred to as 12 to 18 years or 12 to 24 years old) is likely to be underestimated due to youth who are homeless and couch surfing (no fixed address) but report a usual residence in the census. Their homelessness is masked because their characteristics cannot be distinguished from other youth who are just visiting on census night. Therefore, youth will be underestimated within the group ‘persons staying temporarily with other households.’

Another group that are difficult to enumerate are those experiencing homelessness due to domestic and family violence. If the person experiencing violence remains in their unsafe house, this could be considered lack of control of and access to social relations. Due to stigma, some respondents may not identify themselves as having no usual address on the census or have expectations that they may be able to return home in the future and do not see themselves as not having a usual address. Therefore, they cannot be identified as experiencing homelessness on the census. Some respondents may not be enumerated in the census at all, out of fear they may not have themselves recorded on a census form for the dwelling they are staying in.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are under enumerated in the census, and as such estimates of homelessness will be underestimated with census data. There are also different cultural perceptions of homelessness for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This means that some people may not consider their current living situation as homeless but would be classified as homeless under a statistical measure. These people may not seek out homelessness services yet would be included in the census homelessness estimates. The opposite may also occur. For example, a person sees themselves as homeless due to a disconnection from their county and/or family or community but have an adequate living situation. The ABS is working on improving identification of homeless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders for future censuses.

Australia’s Homelessness Enumeration strategy

To supplement the Census approach, the Homeless Enumeration Strategy (HES) ensures quality enumeration and a high response rate on census night. It targets those who are experiencing unsheltered homelessness, hidden homelessness and those staying in supported accommodations for the homeless on census night. The 2016 HES builds off the 2011 HES which uses the experience and knowledge gained from the 1996, 2001, and 2006 censuses.

ABS’s (2012b) core strategies of the 2011 HES include:

- Engage with service providers to assist with the identification of ‘hot spots’ for counting the unsheltered homeless population and recruitment of field/employment staff.

- Standardise training and material for field staff.

- Extend the enumeration period for one week over census night.

- Provide a shortened version of the census form. Allow Census Management Units the flexibility to use long or short census forms to count unsheltered homelessness.

- Increase the accuracy of hidden homelessness count through the promotion of writing ‘None” in the census question asking about usual place of residence.

- Networking with organizations up to one year prior to the census to assist in operational plans. This allows for early identification of ‘hot spots’, refined estimates of unsheltered homeless population in a particular area, access to valuable knowledge from staff and potential collectors and promotion of the census by word-of-mouth throughout homeless population.

- Engage with providers of supported accommodation for the homeless to allow for confidential counting of people staying in these dwellings.

6. Measuring homelessness and potential data development

There are multiple lessons from the Australian example that could help fill data gaps in the current homelessness environment in Canada, these approaches combined with other sources provide a roadmap of potential options for Canada’s next steps. This section looks at the challenges of measuring homelessness, summarizes current data gaps, explores current attempts to fill these gaps, and proposes solutions in terms of developing new data to start addressing some of the data gaps.

Three main challenges should be considered when measuring the homeless population:

(1) Identifying homeless individuals and families in existing sources either for analysis or constructing a survey frame. The homeless population is hard to identify through traditional data collection mechanisms, unlike the general population. Identification of the population is the very first step before developing an effective data collection strategy. Statistical and other organizations generally can’t know without contact that a person is experiencing homelessness. Furthermore, those experiencing homelessness represent a relatively small proportion of the population. The cost and effort required to reach each of these people, through traditional methods, by soliciting each household or dwelling would be disproportionate to the target population.

(2) Developing a collection strategy to effectively connect with homeless individuals and families. None of the typical methods of data collection, such as telephone, mail or the internet used for the general population, are fully adequate to reach this population. This is true for many types of homelessness, if not all, whether it is a person who sleeps outside of shelters, a person who sleeps at a friend's house due to lack of housing or a person who lives with their sibling because of an abusive spouse. However, shelter data, such as HIFIS and other regional or local initiatives can help identify a subset of those experiencing certain types of homelessness but not for all types of homelessness. Furthermore, individual demographic characteristics of the homeless are hard to obtain. Linkage to other sources of data such as administrative data may fill this data gap.

(3) Developing collection methods to safely interview homeless individuals and families while acknowledging the potential trust barrier to overcome. Since it is difficult to obtain information about homelessness and the characteristics of individuals who are experiencing homelessness, it is often considered essential to supplement surveys with interviews. However, this puts a large burden on the interviewers or resource persons tasked with collecting the data. The desired information is often personal and sensitive making asking questions appropriately difficult. For example, how to ask the right questions to know a person's gender, indigenous identity, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.? These are attributes that cannot be observed and which may require asking several questions. Even if several questions are asked, the risk of incorrect interpretation of these questions by the respondents is high. Moreover, finding adequate privacy settings for the interview may be difficult and security for the interviewers is also a consideration.

Measuring homelessness: data gaps and objectives

Given the challenges of measuring homelessness and considering the homeless population, several data gaps exist. Table 6 lists the information contained in each of the databases mentioned in the article. To start addressing these data gaps several objectives can be considered: (1) defining and measuring concepts of homelessness; (2) collecting the appropriate attributes; (3) timing and frequency of collection; and (4) analyzing and measuring pathways/trajectories.

| Data resources | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Housing Survey | General Social Survey | Census | Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse | National Social and Affordable Housing Database | Canada's Core Public Infrastructure Survey | Point-in-time count | National Service Provider List | |

| Type of homelessness | ||||||||

| Homelessness | ✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Unsheltered | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Emergency shelter | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

| Hidden | ✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| At risk | ✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Attributes | ||||||||

| At the time of homelessness experience | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Very limited | ✓ Applicable |

With linkage | Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Retrospective of homelessness experience | ✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Time dimensions | ||||||||

| Point-in-time count | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Lifetime experience | ✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Duration of the episode | ✓ Applicable |

✓ Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Number of episodes | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Chronic homelessness | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Pathways | ||||||||

| Entering homelessness | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Pathways through homelessness | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

| Exiting homelessness | Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

(1) Defining and measuring concepts of homelessness

Defining the different types of homelessness and the concepts that may be used to measure them is crucial in the measurement of homelessness. Although four types of homelessness are commonly used (see Section 2), it is difficult to define them with precise criteria to ensure their accurate measurement. Other countries, such as Australia, rely on six categories, which allow more precise criteria.

Surveys tend to inform on the generic definition of homelessness by combining the four types of homelessness. Surveys such as GSS and CHS include questions on the specific type of hidden homelessness separately. The latest cycle of GSS also includes a question about any experiences of being homelessness because of domestic violence.

Similarly, the census is not a tool to enumerate all the different types of homelessness. However, it does enumerate the homeless population sleeping in shelters across the country on a specific night. The SRFVA also provides information on those living in emergency shelters. However, these two data sources only provide information on the homeless population in contact with the service providers.

From a different angle, CCPI and NSAH can provide information on infrastructure and shelters or shelter capacity but not necessarily many details on those at risk of being homeless or shelter residents.

The unsheltered/chronic homeless population remains very hard to reach beyond the basic point-in-time count exercises.

(2) Collecting the appropriate attributes

From an analytical point of view, measuring homelessness is not only about the counts and the types of homelessness but also about the attributes associated with the individuals experiencing homelessness. The homeless population is hard to identify. Obtaining socio-demographic characteristics directly from a person experiencing homelessness concurrent to the time of the episode of homeless represents a significant challenge.

Matching socio-demographic data to the timing of the homeless experience is critical. Surveys can also provide information on socio-demographics characteristics but only at the time of the survey and not necessarily at the time that homelessness was experienced. The CHS and GSS contain information on individual characteristics such as education, but they are not associated with the timing of experiencing homelessness.

In addition to collecting the appropriate socio-demographics characteristics, a need for disaggregated and regional data is apparent. Different geographic areas such as Toronto or Vancouver don’t face the same issues as Calgary. Labour market shocks and/or weather events for example can be highly localized.

Sample size can also be an issue. Homelessness is experienced by a small proportion of the population. In attempting to measure or disaggregate an event that is infrequent, such as homelessness, it is difficult to obtain sufficient sample size from a general-purpose frame to adequately analyze correlated factors. Uppal (2022) has made progress showing the possibility of looking across Canada, at correlation between past experience of homelessness and current characteristics such as belonging to an LGBTQ+ group. Although, cross-tabulations with additional variables can be challenging.

The census provides a larger sample size and includes more socio-demographic characteristics. However, residents of collective dwellings, including shelter residents, are currently not asked to fill in the census long-form questionnaire, which provides information on the highest level of education completed, immigration status or Indigenous identity, for example. Administrative data linkages could start to address some of these data gaps.

(3) Timing and frequency of collection

For the majority, homelessness is not a permanent condition. It commonly presents as a periodic experience and most often of short duration. It fluctuates throughout the year and varies by season. The timing as well as the frequency of the data collections will impact both the population and the type of homelessness being measured.

Accurately measuring the duration of homelessness is important as to not overestimate the number of people experiencing homelessness. It is important to differentiate between hidden, single and short episode homelessness, multi-episode (episodic), and those with long-term uninterrupted homelessness (chronic). A data gap remains as to the measurement of the number of episodes, their duration and chronic homelessness.