Insights on Canadian Society

Online harms faced by youth and young adults: The prevalence and nature of cybervictimization

by Darcy Hango

Text begins

Acknowlegement

This study was funded by Public Safety Canada.

Start of text boxOverview of the study

Using multiple surveys, this article examines cyberbullying and cybervictimization among Canadian youth and young adults aged 12 to 29. With rates of online and social media use being high among young people, there is an increased risk of online forms of bullying and victimization. This paper examines the prevalence of cyberbullying and cybervictimization among young people, with a focus on identifying the at-risk populations, behaviours related to prevalence, such as internet and smart phone usage, and the association of online victimization with other forms of victimization, such as fraud and assault.

- Some young people are more vulnerable to cybervictimization, including Indigenous youth, sexually diverse and non-binary youth, youth with a disability, and girls and women.

- Cybervictimization increases during adolescence and remains high among young adults in their early 20s. It then tapers off in the late 20s.

- Increased internet usage, as well as using smart phones before bed and upon waking, are associated with an increased risk of being cyberbullied.

- For youth aged 12 to 17, not using devices at mealtime, having parents who often know what their teens are doing online, and having less difficulty making friends act as potential buffers against cybervictimization.

- Cybervictimized young adults often change their behaviour, both online—from blocking people and restricting their own access—and offline—such as carrying something for protection.

- Cybervictimized young adults were also more likely to have experienced other forms of victimization such as being stalked and being physically or sexually assaulted.

Introduction

Internet use is now woven into the fabric of Canadian society. It has become a large part of everyday life, whether it is in the context of online learning, remote working, accessing information, e-commerce, obtaining services (including healthcare), streaming entertainment, or socializing. And while nearly all Canadians use the internet to some degree, Canadians under 30 represent the first generation born into a society where internet use was already ubiquitous. As such, it may not be surprising that Canadians under the age of 30 are more likely to be advanced users of the internet, compared to older generations.Note In addition, they often spend many hours on the internet, with this usage increasing during the COVID-19 pandemic, more so than any other age group.Note

Besides proficiency and intensity, the way in which young people interact with the internet is often different from older generations. Previous Statistics Canada research has shown that younger people are more likely than their older counterparts to use social media, more likely to use multiple social media apps, and engage in more activities on these apps.Note This use has been related to some negative outcomes for younger people, including lost sleep and trouble concentrating.Note

Social media and online activities may also place youth and young people at increased risk of cybervictimization or cyberbullying. Numerous studies have investigated both the prevalence and impact of cybervictimization, noting that youth are often at increased risk.Note While comparisons across studies are often difficult because of definitional differences, ages of the youth being studied, and the time frames, there is consensus on the criteria for measuring cybervictimization. These include (1) intentions to harm the victim, (2) power imbalance between the bully and victim, (3) the repeated nature of aggression, (4) use of electronic devices (including phones or computers), and (5) possible anonymity.Note

This article examines cyberbullying among youth and young adults aged 12 to 29 in Canada using four population-based surveys. The Canadian Health Survey of Children and Youth (CHSCY) collects information on cyberbullying among youth aged 12 to 17, while three surveys capture this information for adults aged 18 to 29. These surveys include the Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS), the General Social Survey (GSS-Cycle 34) on Victimization and the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). Each will be used to help paint a picture of cyberbullying of younger people in Canada.Note Definitions and measures of cyberbullying within each of the surveys are detailed in “Cyberbullying content across four Statistics Canada surveys” text box.

The study starts by discussing the prevalence of, and risk factors associated with, cyberbullying among teens aged 12 to 17. This is followed by an analysis of cyberbullying among young adults aged 18 to 29. Along with providing a profile of cyberbullying, another goal is to highlight data and knowledge gaps in this area and potential areas where future surveys and research should focus.

One-quarter of teens experience cyberbullying

In 2019, one in four teens (25%) aged 12 to 17 reported experiencing cyberbullying in the previous year (Chart 1). Being threatened or insulted online or by text messages was the most common form, at 16%. This was followed by being excluded from an online community (13%) and having hurtful information posted on the internet (9%).

Among those aged 12 to 17, rates of cyberbullying increased with age, rising from 20% at age 12 to 27% by age 17. This perhaps reflects an increased use of the internet, and specifically social media usage with age. The largest increase in cyberbullying prevalence related to being threatened or insulted online or by text messages (from 11% at age 12 to 19% at age 17).

Data table for Chart 1

| percentage | |

|---|---|

| Total youth aged 12 to 17 | 25 |

| Hurtful information was posted on the internet | 9 |

| Excluded from an online community | 13 |

| Threatened/insulted online or by text messages | 16 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, 2019. | |

Besides age, the likelihood of being victimized online varied by gender, sexual attraction, Indigenous identity and educational accommodations. Generally, boys and girls have quite similar prevalence of cybervictimization. For instance, about 1 in 4 (24% for boys and 25% for girls) reported that they experienced any of the three forms of cybervictimization. Non-binary teens, however, experienced cybervictimization at significantly higher levels than both boys and girls. Over half (52%) of teens who reported a gender other than male or female said that they were cybervictimized in the past year. The higher prevalence among non-binary teens was seen across all types of cybervictimization. The greatest difference, however, was seen for being excluded from an online community. The proportion of non-binary teens who reported this type of cybervictimization was about three and a half times the proportion recorded for boys and girls (45% versus 12% for boys and 13% for girls).

In addition, youth aged 15 to 17Note who identified as having the same gender attraction had a significantly higher likelihood of being cyberbullied (33%), compared to their peers who were exclusively attracted to a different gender (26%). This increased risk was seen for all types of cyberbullying but was most pronounced for hurtful information being posted on the internet and being excluded from an online community.

First Nations youth (off-reserve) are at greater risk of cyberbullying

First NationsNote youth living off-reserve were more likely than their non-Indigenous peers to have been cyberbullied in the past year. In particular, 34% of First Nations youth reported being bullied online, compared to 24% of non-Indigenous youth. The risk was heightened for certain types of cyberbullying, including having hurtful information posted on the internet and being threatened/insulted online or by text messages. These higher levels of cybervictimization mirror the overall higher rates of victimization for Indigenous people, which could be rooted in the long-standing legacy of colonialism resulting in discrimination and systemic racismNote (Table 1). No significant differences were observed for Inuit and Métis youth.Note

Most racialized groups had either similar or lower prevalence rates of cyberbullying compared to non-racialized and non-Indigenous youth. For example, 16% of the South Asian youth and 18% of Filipino youth said that they had experienced cyberbullying in the past year, much lower than the 27% of non-racialized, non-Indigenous youth who reported being victimized online.

In addition, those born in Canada had a higher likelihood of cyberbullying, compared to the immigrant youth population (26% versus 19%). This was seen for all forms of online victimization. The differences in risk may be due to variations in frequency of going online. Indeed, previous research has shown that immigrants are less likely to be advanced users of the internet, and are more often non-users, basic users or intermediate users.Note

| Population group | Types of cyberbullying | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurtful information was posted on the internet | Threatened/insulted online or by text messages | Excluded from an online community | Any of the 3 types of cyberbullying | |

| percentage | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Boys (ref.) | 7 | 16 | 12 | 24 |

| Girls | 10 | 16 | 13 | 25 |

| Non-binary | 30Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 34Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 45Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 52Note E: Use with cautionNote * |

| Indigenous identity | ||||

| First Nations | 14Note E: Use with caution | 23Note * | 16Note E: Use with caution | 34Note * |

| Métis | 12Note E: Use with caution | 20 | 13Note E: Use with caution | 30 |

| Inuit | 14Note E: Use with caution | 30Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 36Note E: Use with caution |

| Non-Indigenous (ref.) | 8 | 16 | 13 | 24 |

| Racialized group | ||||

| Black | 8 | 16 | 12 | 24 |

| Chinese | 7 | 11Note * | 12 | 22 |

| Filipino | 10 | 10Note * | 7Note * | 18Note * |

| South Asian | 5Note * | 9Note * | 9Note * | 16Note * |

| Not part of a racialized group (ref.) | 9 | 18 | 14 | 27 |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| Canada (ref.) | 9 | 17 | 14 | 26 |

| Outside Canada | 5Note * | 11Note * | 10Note * | 19Note * |

| Gender attractionTable 1 Note 1 | ||||

| Same gender (ref.) | 15 | 22 | 17 | 33 |

| Opposite gender | 9Note * | 18 | 13Note * | 26Note * |

| Youth has an education accomodation | ||||

| Yes | 11Note * | 19Note * | 15 | 27Note * |

| No (ref.) | 7 | 14 | 12 | 23 |

| Don't know | 12Note * | 19Note * | 15 | 29Note * |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

|

||||

Higher likelihood of cyberbullying among youth with education accommodation

Based on results from CHSCY, having an education accommodation, such as an Individual Education Plan (IEP), Special Education Plan (SEP) or Inclusion and Intervention Plan (IIP), places youth at increased risk of cyberbullying. Overall, 27% of youth with some type of education accommodation for learning exceptionalities or special education needs were bullied online, compared to 23% of their peers without accommodation. The risk was greatest when the cyberbullying incidents involved hurtful information being posted on the internet or being threatened or insulted online or by text messages.

The increased risk of cyberbullying among those with an education accommodation peaks at age 16, with 36% of 16 year-olds with an educational accommodation reporting being cyberbullied compared with 24% of youth without an accommodation.Note

Frequent use of social media tied to higher prevalence of cyberbullying among youth

Because of the potential negative impacts of cyberbullying, including the effects on mental wellbeing, it is important to understand the factors that can expose youth to online harm. One of these possible factors relates to the frequency of online activity. The CHSCY asked youth how often they go online for social networking, video/instant messaging, and online gaming. The majority (about 80%) said that went online at least weekly, with 60% saying they went on social network platforms several times a day, and just over 50% reporting that they used video or instant messenger apps at this same level of frequency. About 1 in 3 (32%) teens said that they went online for gaming at least once a day or more.

In general, results from CHSCY show that more frequent social networking, instant messaging use and online gaming had a strong association with an increased risk of cybervictimization. For instance, among youth who stated that they constantly use social networking, video and instant messaging or online gaming, about one-third (34%, 36% or 30% respectively) said that they had been cyberbullied in the past year. Conversely, the proportion reporting cybervictimization drops to around 20% when social networking and video and instant messaging was used less than once a week (22%, 22%, and 24% respectively). The risk decreases even further to less than 15% when youth never utilized social networking or video and instant messaging apps (Table 2).

| Frequency of social media use | Proportion cyberbullied in past year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Boys | Girls | |||||||

| Social networking | Video or instant messaging | Online Gaming | Social networking | Video or instant messaging | Online Gaming | Social networking | Video or instant messaging | Online Gaming | |

| percentage | |||||||||

| Constantly | 34Note * | 36Note * | 30 | 33Note * | 32Note * | 30 | 34Note * | 38Note * | 28 |

| Several times a day | 27Note * | 27Note * | 30 | 26 | 27 | 30 | 27Note * | 27Note * | 29 |

| Once a day (ref.) | 21 | 23 | 27 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 20 | 20 | 29 |

| Weekly | 27 | 24 | 24 | 30 | 27 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 27 |

| Less than weekly | 22 | 20 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 19Note * | 21 | 17 | 29Table 2 Note † |

| Never | 12Note * | 14Note * | 22Note * | 14Note * | 15Note * | 15Note * | 9Note * | 13Note * | 24Table 2 Note † |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Health Survey of Children and Youth, 2019. |

|||||||||

No gender differences were found between social media, video or instant messaging use and cybervictimization.Note For instance, for both boys and girls, the proportion who said they were cybervictimized in the past year was over 30% if they constantly checked their social networking and instant messaging applications, with the risk decreasing similarly with lower levels of use.

The risk of cybervictimization increases with age, from 12 to 17, mirroring the increased frequency in the use of social networking, video and instant messaging as youth age.

Going online more frequently had the same impact on the cybervictimization risk for Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth. That is, going on social media more frequently increased the risk to the same extent for both Indigenous youth and non-Indigenous youth. However, this was not the case for all youth. For instance, the risk associated with more frequent social media and gaming use was greater for non-racialized youth than it was for racialized youth.

Cyberbullying is sometimes related to usage patterns of electronic devices

In addition to frequency of use, usage pattern of electronic devices may also be related to risk. Among youth aged 12 to 17, three-quarters (75%) used an electronic device before falling asleep in the past week. This usage pattern rises from a low of 54% at age 12 to a high of 92% by age 17.

Using electronic devices before going to sleep appears to increase the risk of being cyberbullied. About 27% of youth that used their electronic device before going to sleep were cyberbullied in the past year, compared to 19% who had not used their device before going to sleep. The increased risk was most often related to being threatened or insulted online or by text messages (18% versus 11% who had not used a device before going to sleep) (Chart 2).

Data table for Chart 2

| Yes, a device was used | No, a device was not used (ref.) | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage | ||

| Total youth aged 12 to 17 | 27Note * | 19 |

| Hurtful information was posted on the internet | 10Note * | 5 |

| Threatened/insulted online or by text messages | 18Note * | 11 |

| Excluded from an online community | 14Note * | 10 |

|

||

Use of electronic devices before going to sleep and risk of cybervictimization is fairly constant across age, but appears to be highest at age 15, where 31% had been cybervictimized in the past year. This proportion falls to 16% if they did not use their device before bedtime.

Results suggest that parents may, in some cases, serve as protective agents, by not allowing electronic devices at the dinner table and having a greater knowledge of what their teens are doing online. For most youth (71%), parents did not allow electronic devices during the evening meal. However, 21% of youth said that their parents allowed electronic devices at the evening meal and another 7% said that their family does not eat together.

The association with cybervictimization, especially being threatened or insulted online or by text messages, increases if electronic devices were allowed at dinner (18% versus 15%). However, there are no differences with respect to other types of cybervictimization. The real risk of cybervictimization is not whether a device was used, but whether the family ate together, which can be influenced by financial or other circumstances, such as work schedules or extracurricular activities. Across all types of cybervictimization, 35% of youth who had not eaten dinner with parents reported that they had been cybervictimized in the past year, significantly greater than the 26% of youth who said that electronic devices were allowed at the evening meal, and the 23% who said that electronic devices were not allowed. This risk is strongest for ages 12 and 16.

Parents’ knowledge of youth’s online activities may help lower the association with cybervictimization. Most Canadian youth who go online have some types of rules or guidelines established by their parents, which is usually more stringent for younger children and is typically relaxed as they age and gain more trust.Note

In 2019, the proportion who stated that their parents often or always know what they are doing online was quite high. In all, 63% stated this level of parental knowledge, while another 37% said that their parents never or only sometimes knew what they were doing online. Parental knowledge about online activity declines with age. At age 12, 77% of youth state that their parents often or always know what they are doing online, which drops to 51% by age 16 and to 49% by age 17.

As may be expected, increased parental knowledge of teen’s online activity was associated with a lower risk of cybervictimization (Chart 3). In particular, close to a third of youth (29%) who said their parents never or only sometimes knew about their online activities reported that they had been cybervictimized. This proportion drops to 22% when parents often or always knew what their teen was doing online. A similar pattern is noted regardless of type of cybervictimization experienced.

Data table for Chart 3

| Parents never or sometimes know online activity | Parents often or always know online activity (ref.) | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage | ||

| Total youth aged 12 to 17 | 29Note * | 22 |

| Hurtful information was posted on the internet | 12Note * | 7 |

| Threatened/insulted online or by text messages | 20Note * | 13 |

| Excluded from an online community | 15Note * | 12 |

|

||

Youth who have difficulty making friends are most vulnerable to online victimization

Based on previous research,Note knowing more people and having more friends, especially close friends can perhaps shield youth from being victimized, and if they are victimized, having friends can perhaps offset some of the negative impacts. Therefore, it is expected that individuals who have a difficult time making friends may be at greater risk of being victims of cyberbullying, as the person or persons victimizing them may believe them to be easier targets of abuse.

In general, across all youth aged 12 to 17, most do not have any difficulty making friends, based on responses from parents. Just over 80% of parents reported that their teen had no difficulty in making friends, while 15% said that their teen had some difficulty and around 4% said that they had a lot of difficulty or could not do it at all. Across individual ages, these proportions are similar. Also, boys and girls have very similar patterns of ease of making friends (parents of around 80% of both boys and girls said that they had no difficulty making friends).Note It bears mentioning that these are parents’ reports about their child’s purported difficulty making friends and therefore may not be the most accurate. Parents may not be fully aware of how well their child develops friendships, as this information may be intentionally hidden from them.

With respect to cybervictimization, teens that have greater difficulty making friends have a greater risk of being cybervictimized than their peers without any difficulty. For example, 23% of youth whose parents said they have no difficulty making friends reported that they had been victims of cyberbullying in the past year. This proportion climbs 12 percentage points to 35% if teens had a lot of difficulty or were unable to make friends (Table 3). A similar pattern was observed regardless of the type of cyberbullying.

The relationship between the ease of making friends and cyberbullying was seen across all ages, though the gap appears to be greatest at age 16. For example, almost half (44%) of 16-year-old teens who had trouble forming friendship were cyberbullied, compared with 24% who had no difficulty making friends.

Girls were especially vulnerable to cyberbullying when they had trouble making friends.Note Overall, 40% of girls whose parents said had a lot of difficulty making friends, or were unable to do so, were cybervictimized. This compares to 23% of girls who had no difficulty making friends. The corresponding difference for boys was much lower, with 28% being cyberbullied if they had trouble making friends and 23% without any difficulty.

| Cyberbullying type, age and gender | Difficulty making friendsTable 3 Note 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulty (ref.) | Some difficulty | A lot of difficulty or Cannot make friends | |

| percentage | |||

| Total youth aged 12 to 17 | 23 | 32Note * | 35Note * |

| Type of cyberbullying | |||

| Hurtful information was posted on the internet | 7 | 14Note * | 15Note * |

| Threatened/insulted online or by text messages | 15 | 22Note * | 22Note * |

| Excluded from an online community | 12 | 18Note * | 24Note * |

| Age | |||

| 12 years | 18 | 27Note * | 29 |

| 13 years | 21 | 32Note * | 32 |

| 14 years | 22 | 28 | 39 |

| 15 years | 27 | 32 | 28 |

| 16 years | 24 | 35Note * | 44Note * |

| 17 years | 24 | 40Note * | 39 |

| Gender | |||

| Boys | 23 | 29Note * | 28 |

| Girls | 23 | 35Note * | 39Note * |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Health Survey of Children and Youth, 2019. |

|||

Young adults: Women and young adults most often the target of cybervictimization

The remainder of the study examines the patterns of cybervictimization among young adults aged 18 to 29. To understand cyberbullying among this age group, three population-based surveys were used. These complementary surveys, while differing in survey design and measurement, shed light on the nature of cyberbullying and the young people most at risk.

According to the 2018 SSPPS, 25% of young people aged 18 to 29 experienced some form of cybervictimization, with the most common being receiving unwanted sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages (15%) and aggressive or threatening emails, social media or text messages (13%) (Table 4).

Young women were more often the target of the online abuse, with a prevalence almost double the rate for young men (32% versus 17%). This gender difference was even more pronounced for receiving unwanted sexually suggestive or explicit material, where young women were almost three times as likely to be targeted (22% versus 8%).Note Therefore, the main gender differences appear to be with respect to cybervictimization of a sexualized nature, as there were no differences between men and women on solely aggressive content without sexual content.Note

| Type of cybervictimization | Total | Men | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people aged 18 to 29 | 18 to 21 years (ref.) | 22 to 25 years | 26 to 29 years | Young people aged 18 to 29 | 18 to 21 years (ref.) | 22 to 25 years | 26 to 29 years | Young people aged 18 to 29 | 18 to 21 years (ref.) | 22 to 25 years | 26 to 29 years | |

| percentage | ||||||||||||

| Total | 25 | 31 | 25 | 19Note * | 17 | 25 | 16 | 13Note * | 32Table 4 Note † | 38Table 4 Note † | 34Table 4 Note † | 26Table 4 Note †Note * |

| Received any threatening or aggressive emails, social media messages or text messages where you were the only recipient | 13 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 16Table 4 Note † | 17 | 18Table 4 Note † | 14 |

| You were the target of threatening or aggressive comments spread through group emails, group text messages or postings on social media | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 7 |

| Somone posted or distributed (or threatened to) intimate or sexually explicit videos or images of you without your consent | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Someone pressured you to send, share, or post sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages | 6 | 10 | 5Note * | 4Note * | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 9Table 4 Note † | 16Table 4 Note † | 8Table 4 Note †Note * | 6Note * |

| Someone sent you sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages when you did not want to receive them | 15 | 20 | 17 | 10Note * | 8 | 13 | 8 | 5Note * | 22Table 4 Note † | 27Table 4 Note † | 26Table 4 Note † | 16Table 4 Note †Note * |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces, 2018. |

||||||||||||

For some types of cybervictimization, there was a significantly greater risk for young adults aged 18 to 21, as compared with young adults aged 26 to 29. For instance, about 20% of young adults aged 18 to 21 reported receiving unwanted sexually suggestive or explicit images or messeges in the last year, double the 10% of young adults aged 26 to 29 who said they also received these types of unwanted images or messages. Young adults aged 18 to 21 were also twice as likely to report being pressured to send, share or post sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages (10%) than their older counterparts (5% for ages 22 to 25 and 4% for ages 26 to 29).

The relationship between cybervictimization and age is similar for both men and women, though rates are always higher for women. Both men and women have about a 12-percentage point gap between ages 18 and 21 and 26 and 29 in experiencing any of the five forms of cybervictimization in the past year (25% versus 13% for men, 38% versus 26% for women). With respect to the individual forms of cybervictimization, the largest decreases by age group related to sexual victimization, especially for women. For example, for women, there was about a 10-percentage point decline from age 18-21 to age 26-29 on being pressured to send, share or post sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages (16% to 6%) and receiving unwanted sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages (27% to 16%).

Greater risk of cybervictimization among LGBTQ2 young adults

Data from the SSPPS also show that LGBTQ2Note young adults were more likely than their non-LGBTQ2 counterparts to have experienced cybervictimization (49% versus 23%).Note ,Note Moreover, the decrease in the risk of cybervictimization across age groups is not seen among the LGBTQ2 population. That is, the proportion experiencing cybervictimization at ages 18 to 21 and late 20s is similar for LGBTQ2 adults, whereas the prevalence of cyberbullying among non-LGBTQ2 young adults declines by about half between the same ages (30% at age 18 to 21 to 18% at ages 26 to 29). Interestingly, among the LGBTQ2 population, the age group with the highest rates of cybervictimization are young adults aged 22 to 25 (at 58%). This is a rare instance of a nonlinear age trend with respect to cybervictimization declining from age 18 to age 29.Note

First Nations young adults are more frequently the victims of cyberbullying

Almost half (46%) of First Nations young people living off-reserve had experienced some form of cyberbullying in the preceding year. This was nearly double the share of non-Indigenous young adults (26%). There was no increased risk among Métis or Inuit young people.Note

Among racialized groups, the likelihood of being cyberbullied was similar to the non-racialized, non-Indigenous population. There was also no difference in risk by immigrant status.

| Selected characteristics | percentage |

|---|---|

| Total | 25 |

| Gender | |

| Men (ref.) | 17 |

| Women | 32Note * |

| Racialized population | |

| Black | 23 |

| Chinese | 19 |

| Filipino | 16 |

| South Asian | 18 |

| Non-racialized (ref.) | 27 |

| Immigrant status | |

| Immigrant (ref.) | 20 |

| Canadian-born | 27 |

| Indigenous identity | |

| First Nations | 46Note * |

| Métis | 31 |

| Inuit | 13 |

| Non-Indigenous (ref.) | 26 |

| Disability | |

| No | 17Note * |

| Yes (ref.) | 39 |

| Sexual/gender diversity | |

| LGBTQ2 (ref.) | 49 |

| Non-LGBTQ2 | 23Note * |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces, 2018. |

|

Young adults with a disability are more often targeted

Young adults aged 18 to 29 with a disabilityNote were significantly more likely to report that they were cybervictimized in the past year. Across all forms of cybervictimization measured in the SSPPS, 39% of young adults with a disability reported having experienced cyberbullying in the past year, compared with 17% of the nondisabled young adult population (Table 5).Note

The SSPPS also allows for the examination of gender differences among young men and women with a disability. Almost half (46%) of women with a disability had experienced cybervictimization in the past year, much higher than the 22% of women without a disability. The difference for men was less marked. In 2018, 27% of men with a disability were targeted online, compared to 14% of other young men.

The severity of the disability also appears to heighten risk. Based on the SSPPS, 56% of young adults with a severe to very severe disability stated that they had been cybervictimized in the past year, while 46% with moderate disability and 34% of those with a mild disability stated the same. This compares to 17% of young adults without a disability that experienced cybervictimization in the past year.Note

Frequent smart phone use is related to cybervictimization

Being continually connected to the Internet is common among young adults aged 18 to 29, though this may place them at increased risk. Over half (55%) checked their smart phone at least every 15 to 30 minutes, with another one-third (30%) checking their smart phone at least once per hour on a typical day. Heavy cell phone use, defined as checking at least every 5 minutes, was the least common, with 15% of youth falling into this category. However, heavy use was more prevalent in the younger age groups. In 2018, 17% of young adults aged 18 to 20 were heavy users, falling to 11% among those aged 27 to 29.

The majority, around three quarters, of young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 also stated that the last thing they do before going to sleep is check their phones, and a similar percentage stated that they do this again first thing upon waking up. The rates of checking before bed and upon waking are very similar regardless of gender and age. About 4 out of 5 (82%) young adults aged 18 to 20 checked their phones when waking up, and 71% of young adults aged 27 to 29 did the same. This difference, however, was not statistically significant.

A pattern, albeit weak, emerges showing that more frequent smart phone use is associated with more online victimization. Based on data from the CIUS, 15% of young adults who used their smart phone at least every 5 minutes said that they had been cybervictimized in the past year. This was double (statistically significant at the p < 0.10 level) the rate of young adults who checked their phone less often (7%)Note . There were no significant differences on whether one used the smart phone before going to bed or after waking up and cybervictimization in the past year.

While a direct comparison cannot be made with the data from the CHSCY on ages 12 to 17 presented earlier, it is interesting to note that among 12-to-17-year-olds there was a significant association between using one’s electronic device at bedtime and risk of cybervictimization, with a higher risk noted especially for teens age 12 and age 15.

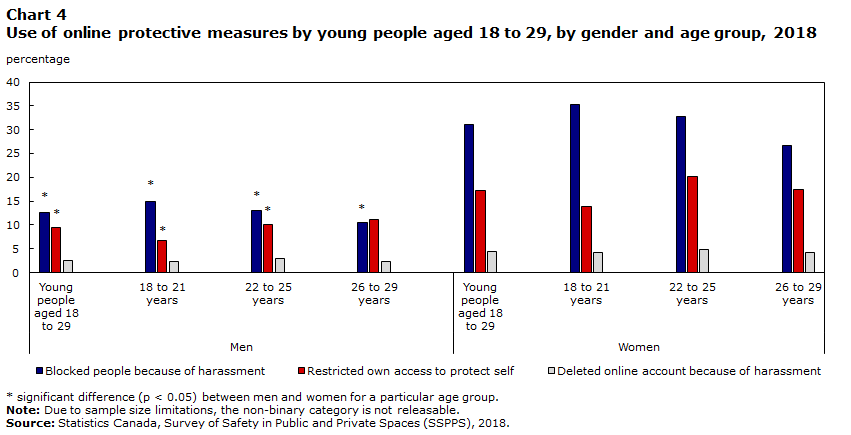

Using protective measures online is more common among younger women

Being victimized online can also lead people to pull back from social media and other online activities. For example, information from the SSPPS shows that about 22% of young adults aged 18 to 29 said that in the past year, they blocked people on the internet because of harassment, while 13% said they restricted their access to the internet to protect themselves from harassment. A further 3% deleted their online account because of harassment.

Young women were twice as likely as young men to block people because of harassment (31% versus 13%) and to restrict their own access (17% versus 10%) (Chart 4). These gender differences may be driven by the higher overall cybervictimization rates for women.Note

Data table for Chart 4

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people aged 18 to 29 | 18 to 21 years | 22 to 25 years | 26 to 29 years | Young people aged 18 to 29 | 18 to 21 years | 22 to 25 years | 26 to 29 years | |

| percentage | ||||||||

| Blocked people because of harassment | 13Note * | 15Note * | 13Note * | 11Note * | 31 | 35 | 33 | 27 |

| Restricted own access to protect self | 10Note * | 7Note * | 10Note * | 11 | 17 | 14 | 20 | 17 |

| Deleted online account because of harassment | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), 2018. |

||||||||

Limiting online activities as a response to cybervictimization is not surprising. Results from the GSS show a strong association between being victimized online and taking other precautions for one’s safety beyond unplugging from the internet. For example, when asked if they do certain things routinely to make themselves safer from crime, young adults aged 18 to 29 who had been cybervictimized in the past year were much more likely to say that they carry something for defense, such as a whistle, a knife or pepper spray, compared with young adults who had not experienced online victimization (12% versus 3%).

Cybervictimization associated with other forms of victimization among young people

There is often a strong association between different types of in-person victimization.Note This is also the case for cybervictimization. Young adults who have been cybervictimized were more likely to be victims of fraud, more likely to have been stalked and also more likely to have been physically or sexually assaulted in the past year.

Data from the GSS showed a connection between cybervictimization and risk of fraud. For example, 17% of young adults who had been cybervictimized in the past year said that they had also been a victim of fraud in the past year, more than four times higher than young adults who had not experienced cybervictimization (4%).Note

Cybervictimization is also highly correlated with other forms of victimization and behaviour. For instance, information from the SSPPS shows that young adults who have experienced unwanted behaviours in public that made them feel unsafe or uncomfortable had also been victims of online harassment and bullying in the past year.Note About 45% of young adults who had experienced such behaviours had been cybervictimized in the past year, compared with 11% who had not experienced such behaviours (Table 6).

The relationship between online victimization and unwanted behaviours in public appears to be similar for men and women. In particular, 41% of men and 46% of women who had experienced unwanted behaviours in public had also been cybervictimized. This compares to around 10% of men and women who had not experienced such incidents.Note Cybervictimization may manifest itself in real-world public encounters because victims of online abuse may be highly sensitized to possibly unsafe or uncomfortable situations in public, especially in instances where the identity of the online abuser is not known. For all they know, the person making them feel unsafe or uncomfortable in public might be the very same person harassing them online.

| Gender | Felt unsafe or uncomfortable in publicTable 6 Note 1 | StalkedTable 6 Note 2 | Experienced physical/sexual assault Table 6 Note 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (ref.) | No | Yes (ref.) | No | None (ref.) | One incident | Two or more incidents | |

| percentage | |||||||

| Total young people aged 18 to 29 | 45 | 10Note * | 67 | 22Note * | 21 | 54Note * | 64Note * |

| Men | 41 | 10Note * | 57 | 16Note * | 15 | 44Note * | 54Note * |

| Women | 46 | 11Note * | 72 | 29Note * | 27 | 62Note * | 70Note * |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces, 2018. |

|||||||

According to the SSPPS, young adults who have been stalked in the past year have also been victims of online bullying and harassment in the past year.Note For instance, 67% of young adults who stated that they had been stalked in the past year also stated that they had been cybervictimized in the past 12 months, three times higher than young adults who had not been stalked in the past year (22%). The relationship is similar for both men and women, with over 72% of women and 57% of men who had been stalked also stating that they had been cybervictimized. Being a victim of stalking is more prevalent among women in general, as 32% of women stated they had been stalked, significantly greater than the 17% of men who stated that they had been stalked.Note

A connection between online victimization and physical and sexual assaults also exists.Note Overall, among victims of physical and sexual assault, the proportion that said they were also cybervictimized was very high. In 2018, 54% of physical or sexual assault victims reported being cybervictimized, climbing to 64% if young people had experienced two or more incidents of physical or sexual assault. The strong association is present for both young adult men and women, with consistently higher prevalence for women regardless of number of physical or sexual assaults.

Perpetrators of online victimization are most often men and known to the victim

An important area of research on cybervictimization that is often lacking relates to the gender of the offender and the relationship between the offender and the victim. Using the SSPPS, it is possible to understand the characteristics of the perpetrator in cybervictimization incidents (Chart 5). About two-thirds (64%) of young adults who had been cybervictimized stated that a man (or men) was responsible, while 19% said it was a woman (or women), 4% said that it was both, and 13% did not know the gender of their online attacker.

This general pattern was similar regardless of gender of the victim, though for women victims, the perpetrator was much more likely to be a man (or men). For instance, 73% of women who had been victimized stated that their offender(s) was (were) a man/men, while 13% stated that it was a woman or women. In contrast, 45% of men said that it was a man (or men) that was responsible, while 31% stated that their offender(s) was a woman or women. At the same time, 19% of men and 11% of women did not know the gender of their online offender.Note

Data table for Chart 5

| Total | Gender of victim | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male victim (ref.) | Female victim | ||

| percentage | |||

| Male offender | 64 | 45 | 73Note * |

| Female offender | 19 | 31 | 13Note * |

| Both male and female offenders | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| Don’t know | 13 | 19 | 11 |

Source: Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), 2018. |

|||

The SSPPS also has information on the relationship of the offender and victim for the most serious incident of inappropriate online behaviour (combining single and multiple offender incidents). The most common offenders, at 55%, were offenders known to the victim, including friends, neighbours, acquaintances, teachers, professors, managers, co-workers, and classmates, as well as family members or current or former partners including spouses, common-law partners or dating partners. Meanwhile, 45% were offenders who were not known to the victim, including strangers or persons known by sight only. Thus, results show that the perpetrator was known to the victim in more than 50% of cases, regardless of the gender of the victim. Based on the SSPPS, 53% of men victims and 56% of women victims knew the person victimizing them online.

Conclusion

Internet and smart phone use among youth and young adults in Canada is at a very high level, particularly since the pandemic. It is a tether to the outside world, allowing communication with one another, expanding knowledge, and being entertained. It is this importance and pervasiveness that makes it particularly challenging when there are risks of online victimization. A goal of this study was to highlight the current state of cybervictimization among Canadian youth and young adults aged 12 to 29. Four separate surveys were used to paint a picture of who is most at risk of cybervictimization, how online and offline behaviours may contribute to this association, and the association with other forms of victimization.

Based on the analysis of the data, there are five key messages related to cybervictimization of youth and young adults:

- Not all youth and young adults experience cybervictimization equally. Those that are most vulnerable to online harm were youth aged 15 -17 with same-gender attraction or, more broadly, LGBTQ2 young adults aged 18-29, youth and young adults with a disability, Indigenous youth, and young adult women when the cybervictimization measures were more of a sexual nature.

- Cybervictimization increases during adolescence and remains high among young adults in their early 20s. The risk drops somewhat as young adults approach age 30. This age pattern was found using two surveys that allowed for prevalence estimates by smaller age groupings (CHSCY and SSPPS). The prevalence estimates were not completely comparable across ages 12 to 29, but the pattern remained.

- Greater internet use, as well as using devices at bedtime and upon waking up was associated with being cybervictimized. Potential buffers of this connection especially for the teenage population (ages 12-17) were not using devices at mealtime, having parents who often know what their teens were doing online, and having less difficulty making friends.

- Taking action to make themselves safer was seen for youth and young adults who have been cybervictimized. This included blocking people online, restricting their own internet access, and carrying something for protection when offline.

- Experiencing other forms of victimization was more common among those who were cybervictimized. This includes being stalked and being physically or sexually assaulted, and experiencing other types of unwanted behaviours in public.

The benefits of the internet for the youth and young adult population are numerous, however, as this study has illustrated, there are certain risks associated with the anonymity and widespread exposure to many unknown factors while online. Knowing the socio-demographic factors and internet use patterns associated with cybervictimization can help tailor interventions to better prevent and respond to cybervictimization. Future analytical work should continue to better understand online victimization faced by youth and young adults.

Darcy Hango is a senior researcher with Insights on Canadian Society at Statistics Canada.

Start of text box

Data sources, methods and definitions

Four surveys are used in this paper: (1) Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), 2019; (2) Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS),2018-2019; (3) General Social Survey GSS on Victimization (cycle 34): 2019-2020, and (4) Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS): 2018.

The analysis is split into 2 separate broad age groups: ages 12 to 17 is examined using the CHSCY, and ages 18 to 29 is examined using the CIUS, the GSS, and the SSPPS.

There remain data gaps in cybervictimization. For instance, there is a need for more information on the perpetrators of cybervictimization. This may involve adding more follow-up questions on existing surveys, whether it is CHSCY or victimization surveys. Moreover, information on specific types of social media platforms, such as social networking sites, image-based sites and discussion forums would be helpful to pinpoint which applications are seeing the most incidents of cyberbullying.

As internet use and potential harm is not restricted to people aged 12 and older, it would be critical to understand the prevalence and nature of cybervictimization for the youngest Canadians, those under the age of 12, recognizing that survey adaptation and ethical considerations would need to be considered.

Lastly, certain population subgroups are more at risk of cybervictimization than others and the research for this study revealed that an inadequate sample size for some groups, such as Indigenous youth and young adults, as well as sexually and gender diverse youth and young adults, limits the ability to understand the dimensions of the issue for these populations. As such, it is necessary to consider oversampling certain groups to produce meaningful cybervictimization estimates.

An additional concern, overarching many of the above issues, is the “digital divide”, particularly affecting communities in rural areas and the north. Recent statistics reveal that in 2017, 99% of Canadians had access to long term evolution (LTE) networks, though this was true for only about 63% of Northern residents.Note The disparity in connectivity may have an adverse impact especially for the Indigenous population in terms of not only Indigenous youths’ underrepresentation in Canadian data on cyberbullying, but also digital literacy initiatives in Northern or in First Nations and Inuit communities.

Cyberbullying content across four Statistics Canada surveys

1. Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), youth aged 12 to 17 years, 2019 (data collection period between February and August 2019)

During the past 12 months, how often did the following things happen to you?

- Someone posted hurtful information about you on the Internet

- Someone threatened or insulted you through email, instant messaging, text messaging or an online game

- Someone purposefully excluded you from an online community

2. Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS), people aged 15 years and older, 2018-2019 (data collection period between November 2018 and March 2019)

Universe: Internet users in the past 3 months

During the past 12 months, have you felt that you were a victim of any of the following incidents on the Internet?

Did you experience?

- Bullying, harassment, discrimination

- Misuse of personal pictures, videos or other content

- Other incident

3. General Social Survey GSS on Victimization (cycle 34), people aged 15 years and older, 2019-2020 (data collection period between April 2019 and March 2020)

Universe: Internet users in the past 12 months

In the past 5 years, have you experienced any of the following types of cyber-stalking or cyber-bullying?

This can be narrowed down to past year by the following question: “You indicated that you experienced some type of cyber-stalking or cyber-bullying in the past 5 years. Did any occur in the past 12 months?”

- You received threatening or aggressive emails or instant messages where you were the only recipient

- You were the target of threatening or aggressive comments spread through group emails, instant messages or postings on Internet sites

- Someone sent out or posted pictures that embarrassed you or made you feel threatened

- Someone used your identity to send out or post embarrassing or threatening information

- Any other type

4. Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), people aged 15 years and older, 2018 (data collection period between April and December 2018)

Universe: Internet users in the past 12 months

Indicate how many times in the past 12 months you have experienced each of the following behaviours while online.

- You received any threatening or aggressive emails, social media messages, or text messages where you were the only recipient

- You were the target of threatening or aggressive comments spread through group emails, group text messages or postings on social media

- Someone posted or distributed, or threatened to post or distribute, intimate or sexually explicit videos or images of you without your consent

- Someone pressured you to send, share, or post sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages

- Someone sent you sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages when you did not want to receive them

- Date modified: