Insights on Canadian Society

Upgrading and high school equivalency among the Indigenous population living off reserve

by Vivian O’Donnell and Paula Arriagada

Start of text box

Among people who leave high school prior to completion, many return to schooling as adults. High school equivalency programs (such as a General Educational Development or Adult Basic Education program) gives them the opportunity to go back and complete high school requirements. Using data from the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey, this study examines the factors associated with upgrading and high school equivalency among the Indigenous population living off reserve. It also examines whether high school equivalency or upgrading is associated with better educational and labour market outcomes.

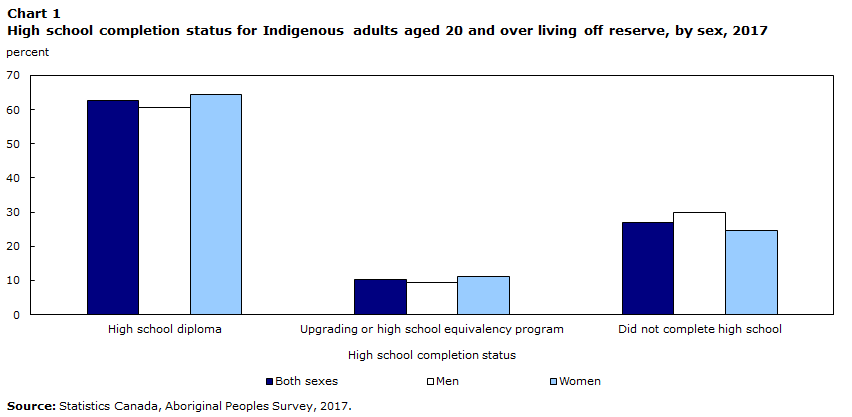

- In 2017, 10% of Indigenous adults aged 20 years and over living off reserve had completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program. About 63% had completed a standard high school diploma and 27% had less than high school qualifications.

- Indigenous adults living off reserve who were aged 45 and over, who had a family history of residential school attendance, who had a disability or who became parents before age 20 were more likely to have completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program.

- Over half (53%) of Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve who completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program went on to obtain a postsecondary diploma or degree. This proportion was lower than those who had obtained a standard high school diploma (65%) but higher than those with no high school qualifications (22%).

- Among Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve who completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program, the probability of being employed was 68% for those who also had postsecondary credentials and 58% for those who did not have postsecondary qualifications. The probability of being employed was lower among Indigenous adults who did not complete high school (46%).

- Among Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve with no postsecondary qualifications, there was little difference in employment probabilities between those who had received a standard high school diploma and those who had obtained a high school equivalency or upgrading.

End of text box

Introduction

Canada has one of the highest levels of educational attainment in the world. In 2016, more than half (54%) of Canadians aged 25 to 64 had either college or university qualifications—as a result, Canada ranked first in the proportion of college and university graduates among the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).Note However, despite these numbers, many students leave high school every year without earning a diploma.

Individuals who do not complete a high school diploma often face less favourable labour market outcomes. Specifically, they have greater difficulty obtaining well-paying jobs and are more vulnerable to economic downturns.Note Furthermore, having a high school diploma helps secure higher earnings and additional years of employment.Note

The impact of finishing high school on economic outcomes may be particularly important for the Indigenous population.Note In 2012, for example, research found that off-reserve First Nations people who had completed high school were more likely to be employed than those who did not finish high school. The same was true among the Métis and Inuit populations.Note However, while the overall educational attainment among Indigenous people continues to improve, relatively high percentages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit do not have high school qualifications.Note Furthermore, research demonstrated that the employment rates of young Canadian adults without a high school diploma are at their lowest point in over 20 years,Note and that a rising proportion of young adults with less than a high school diploma were not in employment, education or training.

What is missing from this discussion is the fact that, among individuals who leave high school before completion, many return to schooling as adults. This second-chance system gives them the opportunity to go back and complete high school requirements, potentially improving their access to postsecondary education and labour market prospects. Many paths are available to those who wish to return to formal schooling or upgrade their credentials—adult learners, many with family and employment responsibilities, have different challenges and considerations than their younger counterparts as they navigate these paths.

Depending upon the province or territory, the second-chance system includes a number of different programs that may be considered upgrading or high school equivalency. Adult learners can pursue a modified diploma recognized as equivalent to a regular high school diploma, or they can write the General Educational Development (GED) test, an international testing program administered by the American Council on Education. Several postsecondary institutions offer academic upgrading for individuals without a high school diploma who want to pursue postsecondary qualifications. Some examples include Adult Basic Education (ABE) courses and the Academic and Career Entrance (ACE) certificate.Note

Little research has been conducted on the outcomes of participation in upgrading or high school equivalency programs in Canada. Studies in the United States have found that GED recipients report marginally higher wages than those without high school completion, but fare worse than those with a high school diploma.Note Similar findings have been reported for postsecondary attendance rates: GED recipients have higher attendance rates than those without a high school diploma, but remain behind traditional high school graduates.Note

A review of research on adult learning did not find any Canadian evidence on the labour market outcomes of GED recipients.Note However, some studies more generally examine the labour outcomes of different levels of schooling.Note For example, a study of labour market outcomes among graduates and dropouts found that men who finish their high school certification after age 19 perform like dropouts at many levels. Moreover, the authors questioned the resources allocated to second chance and adult education programs across Canada and suggested that these could be redirected toward supporting youth before they drop out.Note Other researchers, however, stress that many individuals who missed out on high school or postsecondary completion in youth have benefited from returning to formal education as adults.Note

Because of the limited research on this specific topic in Canada,Note it is important to examine these issues further. This is particularly important for the Indigenous population since a large proportion of them complete a high school upgrading or equivalency program. In this case, it is necessary to focus on the characteristics of individuals who have chosen paths such as upgrading or equivalency, and to also look into whether these programs lead to increased educational attainment or improved labour market outcomes.

Data for this study come from the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), a national survey of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit aged 15 and over (see the Data sources, methods and definitions section). The outcome of interest is high school upgrading or equivalency and how it relates to postsecondary schooling and labour force participation. The data can also be used to compare Indigenous adults who have less than high school qualifications, who have completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program, and who have a standard high school diploma.

The first part of the paper presents a brief profile of the high school completion status of the Indigenous population aged 20 and over living off reserve. This is followed by an examination of the characteristics associated with upgrading or high school equivalency among this population. The results are presented for the total Indigenous population living off reserve and for each group separately, whenever possible.Note The final part of the paper adds to the limited existing research by examining, in both bivariate and multivariate models, the association of high school upgrading or equivalency with selected outcomes for Indigenous adults aged 25 and over. This age restriction is applied because of the need to focus on factors such as postsecondary education and labour force participation. Specifically, the following questions are addressed: (1) Does completion of an upgrading or high school equivalency program open up paths to postsecondary schooling? If so, at what levels? (2) Are Indigenous adults with high school equivalency or upgrading faring better in the labour market than those without high school completion? How do they compare with those who have a standard high school diploma?

One in 10 Indigenous adults completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program

In 2017, 10% of Indigenous adults aged 20 years and over living off reserve had completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program, while 63% had received a standard high school diploma and the remaining 27% had less than high school qualifications (Chart 1). It is important to note that high school completion status does not necessarily refer to the highest level of educational attainment. Individuals with or without a high school diploma may have obtained further education and may have a certificate, diploma or degree beyond the high school level.

Data table for Chart 1

| High school diploma | Upgrading or high school equivalency program | Did not complete high school | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Both sexes | 62.7 | 10.4 | 26.9 |

| Men | 60.7 | 9.4 | 29.9 |

| Women | 64.3 | 11.2 | 24.5 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. | |||

There are differences in high school completion status by sex. Specifically, among Indigenous adults aged 20 and over living off reserve, women were more likely than men to have a standard high school diploma (64% of women compared with 61% of men). Furthermore, Indigenous women were less likely to have less than a high school education than their male counterparts (25% of women compared with 30% of men). Finally, there are also differences by sex in terms of returning to school. In this case, the results show a higher proportion of high school upgrading or equivalency among Indigenous women aged 20 and over who were living off reserve (11%) than among their male counterparts (9%).

The improving education profile of the off-reserve Indigenous population is evidenced by the higher percentages of young people with a high school diploma, compared with older age groups. While 77% of Indigenous people aged 20 to 24 living off reserve had a high school diploma, the percentage of those aged 55 and over with a high school diploma was significantly lower, at 46% (Table 1). Conversely, there are higher percentages of off-reserve Indigenous adults without high school qualifications among the older age groups. Specifically, 39% of older adults aged 55 and over did not complete high school, compared with 19% of young people aged 20 to 24.

| High school diploma | Upgrading or high school equivalency program | Did not complete high school | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Age group | |||

| 20 to 24 | 77.4Note * | 3.3Note * | 19.4 |

| 25 to 34 (ref.) | 70.6 | 6.6 | 22.8 |

| 35 to 44 | 72.1 | 8.8 | 19.0 |

| 45 to 54 | 60.2Note * | 13.3Note * | 26.5 |

| 55 and over | 46.2Note * | 14.9Note * | 38.9Note * |

|

|||

Characteristics associated with upgrading and high school equivalency

This section of the paper focuses on upgrading and high school equivalency and their associated factors for the overall Indigenous population living off reserve, as well as for First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit separately. It includes selected demographic characteristics, as well as family history of residential school attendance, disability status and parenthood status.

Demographic characteristics

Table 2 presents the percentage of adults aged 20 and over who have completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program for each Indigenous identity group. The results show very little difference among the three groups: about one in ten of Inuit, Métis and First Nations people living off reserve had completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program. There are, however, differences in high school completion for each Indigenous identity group. In this case, 60% of First Nations people living off reserve had received a standard high school diploma, compared with 68% of Métis and 38% of Inuit (see Table A1 in the Supplementary information section for more information on high school completion status by selected characteristics).

| Total Indigenous identity population (off reserve) | First Nations people living off reserve | Métis | Inuit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Total | 10.4 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 9.7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (ref.) | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 8.2 |

| Female | 11.2Note * | 11.7 | 10.6 | 11.0 |

| Age group | ||||

| 20 to 24 | 3.3Note * | 3.8Note * | 2.7Note * | 3.4Note *Note E: Use with caution |

| 25 to 34 (ref.) | 6.6 | 7.5 | 5.6 | 7.0Note E: Use with caution |

| 35 to 44 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 7.6 | 9.9Note E: Use with caution |

| 45 to 54 | 13.3Note * | 14.1Note * | 12.2Note * | 13.3Note * |

| 55 and over | 14.9Note * | 14.2Note * | 15.6Note * | 15.2Note * |

| Region | ||||

| Atlantic provinces | 13.8Note * | 15.4Note * | 12.2 | 12.7 |

| Quebec | 9.1 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 5.8Note E: Use with caution |

| Ontario (ref.) | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 8.7Note E: Use with caution |

| Prairie provinces | 12.2Note * | 13.4Note * | 11.3Note * | 14.8Note E: Use with caution |

| British Columbia | 9.5 | 9.2 | 9.8 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Territories | 10.7Note * | 11.7Note * | 12.7Note * | 10.0 |

| Residential school family history | ||||

| No (ref.) | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 6.9Note E: Use with caution |

| Yes | 12.5Note * | 12.5Note * | 12.8Note * | 10.8 |

| Not stated | 11.0Note * | 10.5 | 11.7Note * | 9.0Note E: Use with caution |

| Disability status | ||||

| No (ref.) | 9.0 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Yes | 13.3Note * | 13.3Note * | 13.4Note * | 13.6Note * |

| Parenthood status | ||||

| Teenage parent | 19.2Note * | 19.6Note * | 20.7Note * | 11.7 |

| Other parent / childless (ref.) | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.8 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

|

||||

Older Indigenous adults living off reserve were more likely to have completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program than their younger counterparts. While 3% of Indigenous adults aged 20 to 24 reported completing an upgrading or high school equivalency program, this proportion was 13% among those aged 45 to 54, and 15% among those aged 55 and over. The association between age and high school upgrading and equivalency is also evident for off-reserve First Nations, Métis and Inuit adults. The proportion of young adults who completed a high school upgrading or equivalency program is low, reflecting the fact that recent cohorts of Indigenous people are more likely than earlier cohorts to complete a standard high school diploma. However, this may also reflect the fact that many young Indigenous adults who dropped out of high school have not returned to school yet because of work or family responsibilities.

Different upgrading and high school equivalency programs exist across the provinces and territories, and it is therefore important to examine regional variations. Specifically, higher percentages of Indigenous adults living off reserve had completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program in the Atlantic provinces (14%), followed by the Prairies (12%), the territories (11%) and British Columbia (10%). Among the Prairie provinces, the highest proportion of upgrading or high school equivalency among Indigenous adults was in Saskatchewan (16%), followed by Manitoba (12%) and Alberta (10%).

Residential school family history

An important familial factor for Indigenous people that may affect educational pathways is whether they have a family history of residential school attendance. Residential schools, which were often run by churches in partnership with the federal government, existed in Canada from 1830 until the 1990s. The residential school system affected not only those who were forced to attend, but also many generations, including their children. Existing research has found family history of residential school attendance to be related to how well Indigenous children do in school, including the probability of completing high school.Note

The results show that Indigenous adults with a family history of residential school attendance were significantly more likely to complete an upgrading or high school equivalency program than those without a history of family attendance (13% versus 8%, respectively). The same is true for off-reserve First Nations and Métis adults. Furthermore, a family history of residential school attendance also affects whether or not students obtain a high school diploma through regular channels. Specifically, the proportion of Indigenous students who received a high school diploma is greater among those with no residential school family history (71%) than among those with a history of family attendance (57%).

Disability status

Whether a person has a disability is another factor that may influence high school completion.Note Existing research has found that young adults with disabilities are less likely to finish high school and to be employed than those without disabilities.Note Furthermore, the prevalence of disability is higher among Indigenous people than among their non-Indigenous counterparts.Note

The data show a significant relationship between disability and taking part in the second-chance system. Specifically, the proportion of upgrading and high school equivalency was greater among Indigenous adults who reported having a disability (13%) than among those without a disability (9%). This finding is similar for all three Indigenous identity groups. In addition, Indigenous people with a disability were significantly less likely to earn a standard high school diploma compared with those without a disability (53% versus 67%, respectively), and were more likely to leave school without a degree (34% versus 24%, respectively).

Parenthood status

Teenage parenthood is another important factor that has been linked to high school completion status. Existing research on the general population has shown that becoming a parent before age 20 is associated with a lower probability of completing high school or postsecondary education.Note Furthermore, additional research has shown that Indigenous women who were teenage mothers were less likely to have a high school diploma.Note This is consistent with research that has shown reasons for leaving school early differing by sex.Note Specifically, when asked why they left high school before completion, Indigenous women living off reserve cited pregnancy or the need to care for their own children most often (17%), while Indigenous men most commonly cited wanting to work (35%).

The results show that teenage parenthoodNote is not only related to leaving school without a high school diploma, but also associated with returning to school. Specifically, the proportion of off-reserve Indigenous adults aged 20 and over upgrading or completing a high school equivalency program was significantly higher among those who became parents during their teenage years, with almost one in five individuals (19%) choosing this path. This compares with 9% among those who either had children later in life or did not have children. This finding may reflect how the majority of teenage parents are women who likely return to school to improve job prospects, many while caring for children on their own.

When the three Indigenous identity groups are examined separately, the results show that the proportion of individuals who upgrade or complete a high school equivalency program is significantly higher for off-reserve First Nations adults who were teenage parents (20%) than for those who did not have children or had them at a later age (9%). The same is true for Métis, with 21% of those who became parents in their teenage years upgrading or completing a high school equivalency program, compared with 9% for other parents or those without children. The results for Inuit show no significant differences among the different parenthood status groups.

Postsecondary completion higher among Indigenous adults with upgrading and equivalency than those without a high school diploma

For Indigenous adults living off reserve, the results show that upgrading and high school equivalency programs improve the chances of them completing a postsecondary education. In 2017, just over half (53%) of Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve who had completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program earned postsecondary qualifications (Chart 2). This was significantly higher than among those with no high school qualifications (22%)Note , but lower than among those who had received a high school diploma (65%).

Data table for Chart 2

| High school completion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No high school qualifications | Upgrading or high school equivalency | High school diploma | |

| percent | |||

| Postsecondary education credentials | |||

| No postsecondary education qualifications | 64.9 | 27.2 | 18.7 |

| Some postsecondary education (incomplete) | 13.3 | 19.6 | 16.0 |

| Postsecondary education, below bachelor level | 20.6 | 48.9 | 45.3 |

| Postsecondary education, bachelor level and above | 1.2Note E: Use with caution | 4.3 | 20.0 |

|

E use with caution Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

|||

In terms of the specific types of postsecondary qualifications, there are differences based on whether an individual received a standard high school diploma or equivalency. For example, among Indigenous adults with a high school diploma, 20% received qualifications at the bachelor level or above, compared with 4% of those with an equivalency or upgrading. However, the proportions of Indigenous adults with qualifications below the bachelor level were similar: 49% for those with equivalency or upgrading, and 45% for those with a standard high school diploma. These results show that returning to formal schooling can prove beneficial in terms of attending and completing postsecondary education.

It is also possible to use logistic regressions to assess the relationship between high school completion status and postsecondary qualifications to account for other characteristics associated with the completion of a postsecondary education. Results from the model are presented as predicted probabilities. A probability of “1” indicates a 100% chance of completing a postsecondary degree or diploma, while a probability of “0” indicates a 0% chance.

The regression for postsecondary credentials controls for high school completion status, sex, age and region, as well as for other important explanatory factors such as disability status, history of family residential school attendance and parenthood status (see Table A2 in the Supplementary information section for complete regression results). Results for men and women are presented separately.

The multivariate analyses confirm the descriptive results. That is, completing an upgrading or high school equivalency program is significantly associated with postsecondary qualifications among Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve, even after controlling for other variables (Table 3). Specifically, the probability of obtaining any postsecondary credentials was 53% for individuals who completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program, significantly higher than the 22% for those who did not complete high school. However, the probability of obtaining postsecondary qualifications was even higher for those who earned a high school diploma, at 65%.

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| predicted probabilities | |||

| High school completion status | |||

| High school diploma | 0.65Note * | 0.63Note * | 0.67Note * |

| Upgrading or high school equivalency | 0.53Note * | 0.49Note * | 0.57Note * |

| Did not complete high school (ref.) | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.24 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

|||

Furthermore, the returns of upgrading and high school equivalency programs are greater for Indigenous women than for their male counterparts. In this case, the probability of obtaining postsecondary credentials was 57% for Indigenous women, compared with 49% for Indigenous men.

These results show that although an upgrading or equivalency program does not yield the same returns as a high school diploma, it remains a significant predictor of educational attainment at the postsecondary level.

Upgrading and high school equivalency associated with better employment outcomes than not finishing school

The results also show that completing an upgrading or high school equivalency program is positively correlated with being employed (Chart 3). Among Indigenous women aged 25 and over living off reserve who had completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program, more than half (55%) were employed in 2017. This proportion is significantly higher than for those without a high school diploma, at 34%. In comparison, 69% of those with a standard high school diploma were employed.

Data table for Chart 3

| High school completion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not complete high school | Upgrading or high school equivalency | High school diploma | |

| percent | |||

| Women | 34.0 | 54.7Note * | 69.3Note * |

| Men | 49.0 | 58.2Note * | 74.6Note * |

|

|||

In terms of employment for Indigenous men aged 25 and over living off reserve, the proportions were 49% among those without high school qualifications versus 58% among those who had completed an upgrading or equivalency program. At 75%, the proportion was highest among those with a standard high school diploma. Still, these findings show that Indigenous people see benefits in employment from finishing an upgrading or high school equivalency program, but not as much as if they had obtained a standard high school diploma.

Logistic regressions were also used to examine the relationship between high school completion status and employment. In this case, a new variable was created to control for postsecondary education along with high school completion to differentiate Indigenous adults who received a high school diploma or a high school equivalency or upgrading depending on whether or not they also earned any postsecondary credentials. The model also controls for sex, age, region, residential school family history, disability status and parenthood status. Separate results are presented for men and women.

The results again show that there are significant benefits to returning to school for upgrading or high school equivalency programs among Indigenous adults aged 25 and over living off reserve, but they differ depending on whether postsecondary credentials were earned as well.

Specifically, the results indicate that the probability of being employed was 68% for men and women who completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program and postsecondary education, after controlling for other variables (Table 4). This is significantly higher than the 46% probability among those who did not complete high school. For those who completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program but did not obtain postsecondary qualifications, the probability of employment was 58%.

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| predicted probabilities | |||

| High school and postsecondary completion | |||

| High school diploma and postsecondary education credentials | 0.76Note * | 0.79Note * | 0.73Note * |

| High school diploma and no postsecondary education credentials | 0.60Note * | 0.66Note * | 0.56Note * |

| Upgrading or high school equivalency and postsecondary education credentials | 0.68Note * | 0.68Note * | 0.67Note * |

| Upgrading or high school equivalency and no postsecondary education credentials | 0.58Note * | 0.65Note * | 0.51Note * |

| Did not complete high school (ref.) | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.38 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

|||

In addition, the probability of employment was highest among Indigenous adults who earned a standard high school diploma and postsecondary credentials (76%). However, the probability of employment was lower among those who had a standard high school diploma but did not have any postsecondary credentials (60%), which is similar to the probability of employment for those who completed an upgrading or equivalency program but no postsecondary education (58%). This may imply that it is not how a high school diploma was received that is important for future employment, but rather that postsecondary education was also completed.

When the results for employment are examined separately for men and women, a similar pattern emerges. In this case, upgrading and high school equivalency increased the likelihood of employment for Indigenous women living off reserve, but even more so for those who also have postsecondary credentials. The probability of being employed was 67% among Indigenous women who completed an upgrading program and postsecondary qualifications, significantly higher than the 38% among those who did not complete high school. However, among those who completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program but did not obtain postsecondary qualifications, the probability of employment was 51%.

For Indigenous men, upgrading and high school equivalency also result in a higher probability of being employed, compared with those who did not finish high school. Specifically, the probability of employment was 68% for Indigenous men who completed an upgrading or equivalency program and postsecondary qualification, compared with 54% among those who left school without a diploma. Moreover, among Indigenous men with no postsecondary qualifications, there was little difference in the probability of employment based on the completion of a high school diploma (66%) or high school equivalency or upgrading (65%).

Conclusion

While the educational profile of the Indigenous population continues to improve, a relatively large percentage of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit continue to leave high school before completion. However, many return to formal education as adults. This second-chance system provides adults with the opportunity to go back and complete high school qualifications. There is very little research on the characteristics of the individuals who have chosen paths such as upgrading or equivalency, and on whether these programs lead to increased educational attainment or improved labour market outcomes.

In 2017, 1 in 10 Indigenous adults aged 20 and over living off reserve had completed a high school equivalency or upgrading program. This finding is similar for all three Indigenous identity groups. The results also show the differences by sex, with Indigenous women being more likely than Indigenous men to return to formal education as adults. Furthermore, the data show that Indigenous adults who have a disability and those who became parents before age 20 were more likely to take part in the second-chance system.

For Indigenous people living off reserve, the findings from this study show that returning to formal schooling can prove beneficial in terms of starting and completing a postsecondary education. Specifically, just over half (53%) of Indigenous adults aged 25 and over who had completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program went on to receive postsecondary qualifications. This compared with 22% among those with no high school diploma and 65% among those who graduated from high school.

Moreover, the potential benefits of formal adult education are evident when examining labour market outcomes. Results from multivariate analyses show that the probability of employment was higher among those who completed an upgrading or high school equivalency program, particularly if they also had postsecondary credentials, than among those who did not complete high school.

These findings from the 2017 APS suggest that although an upgrading or equivalency program does not yield the same benefits as a high school diploma, returning to school provides opportunities for Indigenous adults to increase their educational attainment, and therefore improve their labour market outcomes. As a result, upgrading and high school equivalency can be seen as a path forward for many youth who are more at risk and may not otherwise work or participate in the postsecondary educational system. Further research could examine in more detail earnings and types of occupations by high school completion status to create a more complete picture of these benefits.

Vivian O’Donnell is a senior analyst and Paula Arriagada is a research analyst with the Centre for Indigenous Statistics and Partnerships at Statistics Canada.

Start of text box 1

Data sources

The 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) is a voluntary, national survey of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit aged 15 and over. The 2017 APS represents the fifth cycle of the survey and focused on the topics of employment, skills and training. It also collected information on education, health, languages, income, housing and mobility.

The survey was developed by Statistics Canada with funding provided by Indigenous Services Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Health Canada, and Employment and Social Development Canada.

The target population of the 2017 APS was the Indigenous identity population of Canada aged 15 years and over as of January 15, 2017, living in private dwellings. It excluded people living on Indian reserves and settlements and in certain First Nations communities in Yukon and the Northwest Territories. For information on survey design, target population, survey concepts and response rates, please consult the Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017: Concepts and Methods Guide.

Methodology

The Indigenous identity question on the APS could be answered with both single and multiple responses. The data presented separately for each group represent a combination of the single and multiple responses for First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit.

All estimates in this report are based on survey weights that account for sample design, non-response and known population totals. A bootstrapping technique was applied when calculating all estimates of variance.

The predicted probabilities in this paper are calculated on the basis of a logistic regression model, using the covariates at their mean value.

End of text box 1

- Date modified: