StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better CanadaThe mental health of population groups designated as visible minorities in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic

StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better CanadaThe mental health of population groups designated as visible minorities in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

This article is the third in an analytical series that uses crowdsourced data to examine the mental health of diverse groups of Canadians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous articles focused on gender (male, female and gender diverse) and place of birth (foreign-born and Canadian born).

It is now well-established that the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the public health measures implemented in its wake to curb the spread of the virus (i.e., social distancing), have taken a toll on the mental health of Canadians (Findlay & Arim 2020; Rottermann 2020; Statistics Canada 2020a & b). What is currently unknown is whether the mental health of Canadians designated as visible minorities has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that close to one quarter (22.3%) of Canadians belonged to population groups designated as visible minorities (hereafter referred to as visible minorities) in 2016, this is an important knowledge gap to fill.

Using data collected through a crowdsource survey from April 24 to May 11, 2020, this article compares the mental health of visible minority groups—specifically, South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, and Arab—and non-visible minorities (excluding Indigenous Peoples) during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the context, resilience and experience of each individual is particular, comparing the mental health of participants from different population groups during the COVID-19 pandemic fosters a better understanding of the specific experiences of diverse groups of Canadians and contributes to Statistics Canada's ongoing efforts to collect and publish disaggregated data on vulnerable populations. Three different measures of mental health are considered: self-rated mental health, changes in mental health since physical distancing began, and symptoms consistent with generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the survey.

Readers should note that, unlike other surveys conducted by Statistics Canada, crowdsourced data are not collected according to a probabilistic sampling design. Therefore, when interpreting findings from these data, no inferences should be made about either the overall Canadian population or its subgroups.

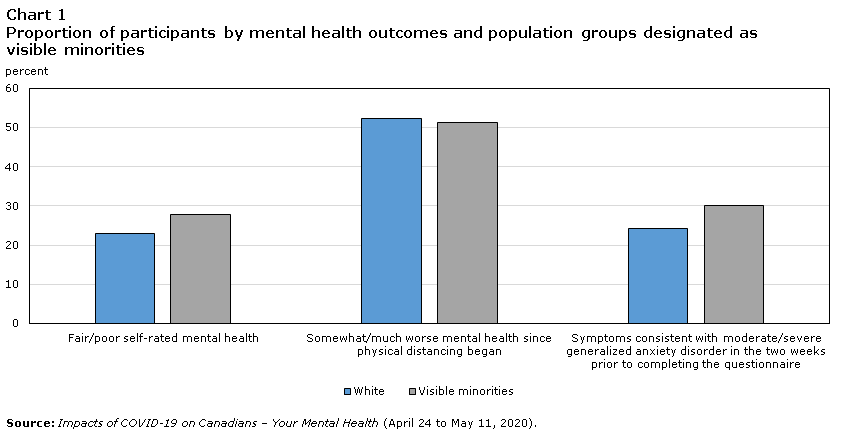

Participants from visible-minority groups have poorer mental health outcomes than White participants

Across most measures of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants from visible-minority groups had poorer outcomes than White participants (Chart 1). Although similar proportions of visible-minority and White participants reported that their mental health was “somewhat” or “much” worse since physical distancing began (51.3% and 52.2%, respectively), a greater proportion of participants from visible-minority groups reported “fair” or “poor” self-rated mental health (27.8% vs. 22.9%). Participants from visible-minority groups were also more likely to report symptoms consistent with “moderate” or “severe” generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the survey (30.0% vs. 24.2%). Generalized anxiety disorder is a condition characterized by a pattern of frequent, persistent worry and excessive anxiety about several events or activities.

Data table for Chart 1

| Fair/poor self-rated mental health | Somewhat/much worse mental health since physical distancing began | Symptoms consistent with moderate/severe generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the questionnaire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| White | 22.9 | 52.2 | 24.2 |

| Visible minorities | 27.8 | 51.3 | 30.0 |

| Source: Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians – Your Mental Health (April 24 to May 11, 2020). | |||

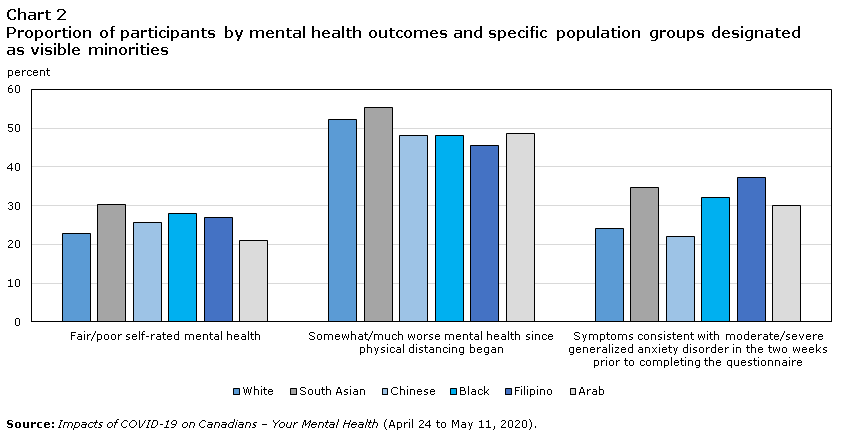

Mental health outcomes differ across visible-minority groups

Considering the five largest visible-minority groups in Canada (i.e., South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, and Arab), as per the 2016 Census of Population, South Asian participants had poorer mental health outcomes than participants belonging to other visible-minority groups (Chart 2). South Asian participants were more likely to report fair/poor self-rated mental health and somewhat/much worse mental health since physical distancing began. South Asian participants were also more likely than participants in other visible-minority groups—with the exception of Filipino participants—to report symptoms consistent with moderate/severe generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the survey.

In some ways, Arab, Filipino and Chinese participants had better self-reported mental health than other visible-minority groups: Arab participants were less likely to report fair/poor self-rated mental health; Filipino participants were less likely to report somewhat/much worse mental health since physical distancing began; and Chinese participants were less likely to report symptoms consistent with moderate/severe generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the survey.

It is important to note that the cultural backgrounds of participants from visible-minority groups may influence how they respond to questions about their mental health.

Data table for Chart 2

| Fair/poor self-rated mental health | Somewhat/much worse mental health since physical distancing began | Symptoms consistent with moderate/severe generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the questionnaire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| White | 22.9 | 52.2 | 24.2 |

| South Asian | 30.3 | 55.3 | 34.6 |

| Chinese | 25.7 | 48.1 | 22.0 |

| Black | 27.9 | 48.1 | 32.0 |

| Filipino | 26.9 | 45.5 | 37.2 |

| Arab | 21.0 | 48.6 | 30.0 |

| Source: Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians – Your Mental Health (April 24 to May 11, 2020). | |||

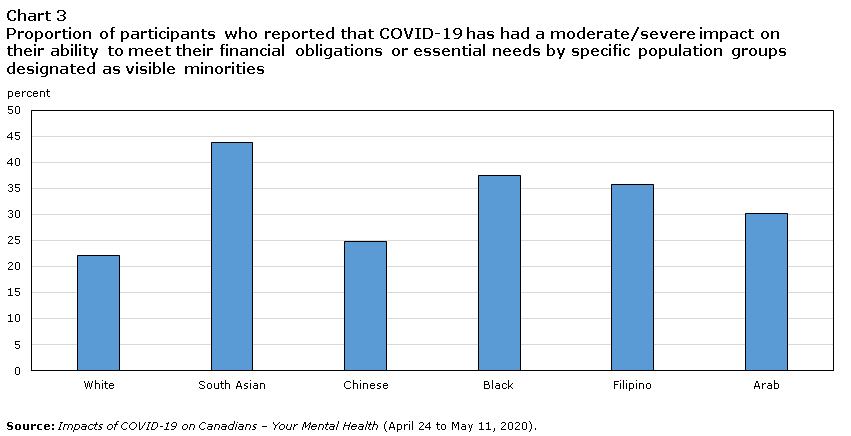

Participants from population groups designated as visible minorities are more likely to report COVID-19-related financial insecurity

Financial insecurity has been linked to lower mental health prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and higher levels of anxiety during the pandemic (Statistics Canada 2020a). Participants from visible-minority groups were more likely than White participants to report that the pandemic has had a “moderate” or “major” impact on their ability to meet their financial obligations or essential needs, such as rent or mortgage payments, utilities and groceries: 35.0% vs. 22.1%. South Asian participants were most likely to report COVID-19 related financial insecurity (43.8%), while Chinese and Arab participants were the least likely to do so (24.9% and 30.2%, respectively) (Chart 3).

Data table for Chart 3

| Moderate/severe impact of COVID-19 on ability to meet financial obligations or essential needs | |

|---|---|

| percent | |

| White | 22.1 |

| South Asian | 43.8 |

| Chinese | 24.9 |

| Black | 37.5 |

| Filipino | 35.7 |

| Arab | 30.2 |

| Source: Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians – Your Mental Health (April 24 to May 11, 2020). | |

Methodology

This article examined differences in the self-perceived mental health of groups designated as visible minorities and Whites during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The term "visible minority" refers to Canadians designated as visible minorities as per the definition in the Employment Equity Act. The Act defines visible minorities as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour.” Visible-minority groups include: South Asian; Chinese; Black; Filipino; Latin American; Arab; Southeast Asian; West Asian; Korean; Japanese; visible minority, not included elsewhere; and multiple visible minorities. To protect the confidentiality of participants, only the five largest visible-minority groups in Canada are disaggregated in this article: South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, and Arab. Indigenous peoples are excluded from the category of non-visible minorities.

This article is based on analyses of data collected through Statistics Canada’s crowdsource survey, “Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians – Your mental health.” This survey was live on Statistics Canada’s website between April 24 and May 11, 2020, and around 46,000 residents of Canada completed it voluntarily.

It is important to note that statistical inferences about the Canadian population cannot be made from participants in crowdsource surveys, as the respondents are self-selected. Respondents to traditional sample-based surveys, on the other hand, are probabilistically selected from the target population. Nevertheless, crowdsourcing is a cost-effective and timely way to collect granular data on a particular topic.

In this article, methodological adjustments were made to account for age, sex and provincial differences.

Physical distancing was defined as making changes in everyday routines in order to minimize close contact with others, including: avoiding crowded places and gatherings, avoiding common greetings such as handshakes, limiting contact with people at higher risk, and keeping a distance of at least two arms’ length from others (approximately two meters).

Anxiety was measured using the GAD-7 scale, which is used in population health surveys to identify probable cases of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) as well as to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a condition characterized by a pattern of frequent, persistent worry and excessive anxiety about several events or activities. Those with a score of 10 or higher on the GAD-7 were considered to have moderate to severe symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the two weeks prior to completing the survey. The data reported do not necessarily reflect a professional diagnosis of GAD. In the context of the COVID-19 outbreak where the population has been unexpectedly exposed to an unprecedented global crisis with wide-ranging impacts including significant disruption to employment, schooling, and routines, and increased health risk, it is important to note that feelings of anxiety can be understood as natural reactions and not necessarily indicators of a long-term mental health disorder.

It is important to note that the cultural backgrounds of participants from visible-minority groups may influence how they respond to questions about their mental health, insofar as culture plays a role in how its member think about and understand mental well-being and illness.

References

Findlay, Leanne and Rubab Arim. 2020. “Canadians report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, catalogue no. 45-28-0001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Rottermann, Michelle. 2020. “Canadians who report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic more likely to report increased use of cannabis, alcohol and tobacco.” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, catalogue no. 45-28-0001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. 2020 a. “Canadians’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.” The Daily (May 27).

Statistics Canada. 2020 b. “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 2: Monitoring the effects of COVID-19, May 2020.” The Daily (June 4).

- Date modified: