StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada

Adults with a health education but not working in health occupations

StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada

Adults with a health education but not working in health occupations

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

by Feng Hou and Christoph Schimmele

Text begins

With the continuing spread of COVID-19, many health-care workers in Canada are facing overwhelming workloads and risk exposure to the virus while caring for their patients. Additional resources and staff may help to reduce the strain on these frontline workers and to increase the capacity of hospitals, clinics, assessment centres, and long-term care facilities.

In 2019, 1,424,300 workers were employed in health occupations. About 54% of them were in technical occupations or assisting occupations in support of health services and the other 46% were in professional occupations (nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and other health diagnosing and treating professionals). Even before the COVID-19 crisis, there were a large number of job vacancies in health occupations. In the third quarter of 2019, about 40,300 jobs in health occupations were unfilled, and the majority of these vacancies were in assistant-level positions (36%), nursing (30%), and technical positions (25%). The demand for workers in these occupations is likely to continue to be strong. Individuals who have a health-related education, but who are not working in a health-related occupation, could be a potential resource for caring for COVID-19 patients and providing essential support services, such as cleaning medical instruments and increasing the capacity for testing.

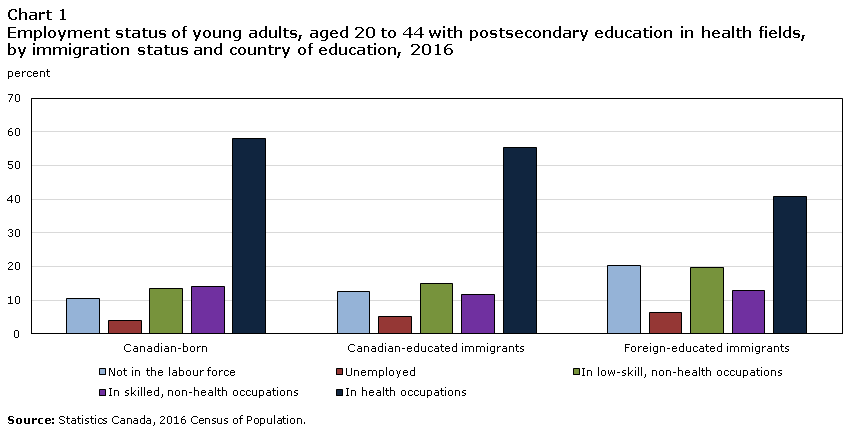

Data table for Chart 1

| Canadian-born | Canadian-educated immigrants | Foreign-educated immigrants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Not in the labour force | 10.4 | 12.7 | 20.3 |

| Unemployed | 4.0 | 5.3 | 6.5 |

| In low-skill, non-health occupations | 13.3 | 14.9 | 19.8 |

| In skilled, non-health occupations | 14.2 | 11.7 | 12.7 |

| In health occupations | 58.1 | 55.3 | 40.7 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. | |||

In 2016, when the latest census was collected, there were 939,000 adults aged 20 to 44 with a postsecondary education in a health-related field.Note About 56% of them held health-related jobs, and 14% held jobs outside their educational field, but which require a postsecondary education. Around 30% were “underutilized” graduates, which refers to people with postsecondary education in a health-related field who are not employed or work in non-health occupations that require no more than a high school diploma. Among the underutilized, 14% were employed in non-health occupations that require no more than a high school diploma, 12% did not participate in the labour force, and 4% were unemployed. There are several possible reasons why some people have an underutilized health education. Some may choose not to work in their educational field, while others may have difficulty obtaining employment in their field.

The share of underutilized adults with a health-related education was lower among Canadian-born individuals (28%) than among foreign-educated immigrants (47%) and immigrants who received their highest level of education in Canada (33%) (Chart 1). The underutilization rate was higher among Indigenous peoples (39%) and visible minorities (39%) than among the White population (27%). Women accounted for 83% of the adults with a health education, and their underutilization rate (31%) was higher than that among men (27%).

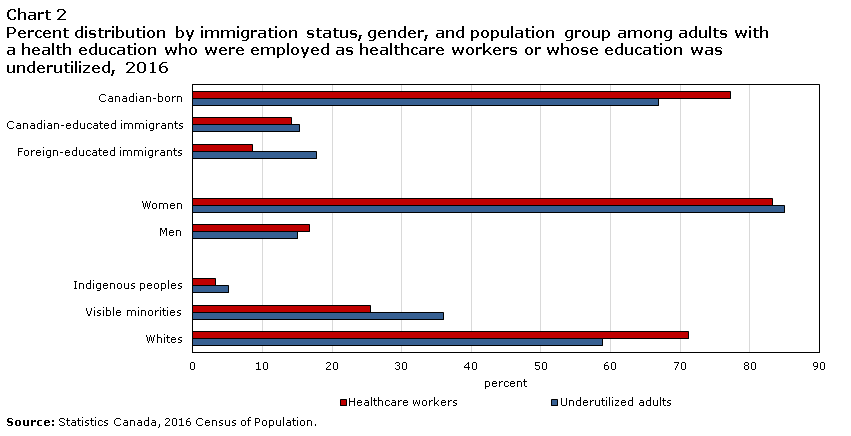

Corresponding to their higher underutilization rate, foreign-educated immigrants were over-represented among underutilized adults relative to their share among adults with a health education and were employed as healthcare workers (Chart 2). Women accounted for 83% healthcare workers, but 85% of underutilized adults. The share of Indigenous peoples and visible minorities among underutilized adults were higher than their shares among healthcare workers.

Data table for Chart 2

| Healthcare workers | Underutilized adults | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Canadian-born | 77.3 | 66.9 |

| Canadian-educated immigrants | 14.2 | 15.3 |

| Foreign-educated immigrants | 8.6 | 17.8 |

| Women | 83.3 | 85 |

| Men | 16.7 | 15 |

| Indigenous peoples | 3.3 | 5.1 |

| Visible minorities | 25.6 | 36 |

| Whites | 71.2 | 58.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. | ||

The estimated number of adults aged 20 to 44 with an underutilized health education increased from 277,300 in 2011 to 288,100 in 2016, although their share among all adults with a health education decreased from 33% to 30%. Given the increased inflow of new immigrants since 2016, assuming a similar share of adults with a postsecondary education in health fields, even if the underutilization rate deceased by a few percentage points, there are still likely over 250,000 adults whose health education is underutilized.

When graduates cannot find a job in their educational field, their skills may become obsolete over time. Among adults whose health-related education was underutilized in 2016, 62% were in the 20-to-34 age group and they were more likely to be recent graduates than those in the 35-to-44 age group. The atrophy of skills is likely to be relatively low among recent graduates, making them a potential source of health-care labour. Even so, some of these recent graduates may have insufficient skills or lack the competencies required for working in health-related jobs.

Place of education is another possible reason for underutilization, as credentials obtained outside Canada are not always treated as the equivalent of a Canadian education and the foreign-educated may face challenges in acquiring professional licences. However, about 67% of underutilized adults were born in Canada, 15% were Canadian-educated immigrants, and 18% were foreign-educated immigrants. Among foreign-educated immigrants, about 31% received their highest level of education in the Philippines, 15% in India, and 4% in China. Only a small share (7%) were educated in the United States, United Kingdom, or France.

Some foreign-educated immigrants with a health-related education may not have a sufficient level of proficiency in English or French for professional settings, although almost all (98%) immigrants whose health-related education was underutilized self-reported that they could speak either English or French. Most (82%) of them also spoke another language and thus could provide an important linguistic and cultural resource for Canada’s diverse ethnic communities. In particular, about 15,100 spoke Tagalog, 6,600 Arabic, 5,500 Punjabi, 4,900 Mandarin or Cantonese, 4,400 Spanish, and 3,700 Persian.

The most common field among underutilized adults was nursing (20% or 57,800 in 2016). It was followed by health aids and attendants (18% or 50,800) and health and medical administrative services (13% or 36,100). The distribution of fields of study were broadly similar for the Canadian born and Canadian-educated immigrants. Among foreign-educated immigrants, the underutilized fields were more concentrated in nursing (34%), medicine (12%), and pharmacy (8%), reflecting well-known obstacles faced by foreign-educated professionals, such as credential recognition. There was also a clear gender difference in the distribution of study fields, with women being more concentrated in nursing (21% vs. 14%), health aids or attendants (19% vs. 12%), and health and medical administrative services (14% vs. 2%) than men.

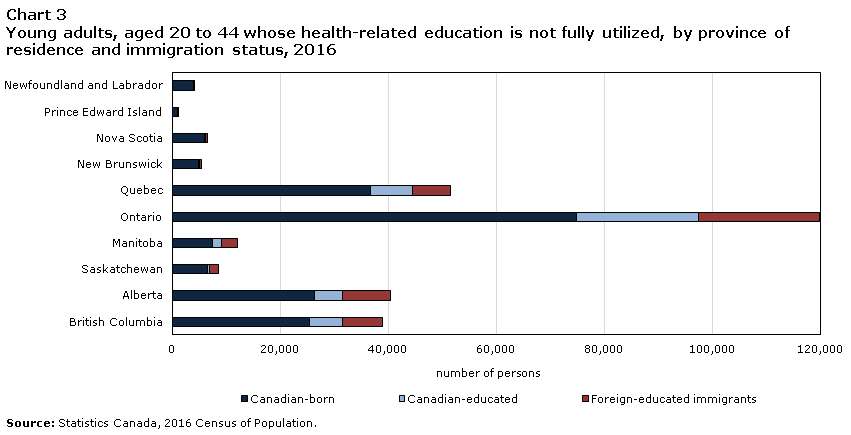

About 42% of underutilized adults with a health education resided in Ontario. Another 18% were located in Quebec, 14% in Alberta, and 13% in British Columbia (Chart 3).

Data table for Chart 3

| Canadian-born | Canadian-educated | Foreign-educated immigrants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of persons | |||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3,850 | 80 | 120 |

| Prince Edward Island | 850 | 10 | 70 |

| Nova Scotia | 5,840 | 190 | 370 |

| New Brunswick | 4,890 | 130 | 250 |

| Quebec | 36,720 | 7,670 | 7,000 |

| Ontario | 74,740 | 22,620 | 22,490 |

| Manitoba | 7,430 | 1,600 | 2,940 |

| Saskatchewan | 6,480 | 390 | 1,640 |

| Alberta | 26,240 | 5,210 | 8,830 |

| British Columbia | 25,290 | 6,170 | 7,370 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. | |||

In a time of crisis and an ongoing shortage of health-care workers, there may be possible pools of labour supply among those whose education is in health care but who are not working in health-related occupations. However, information is lacking on how many of them are readily available and actually capable of performing health-related jobs. As they are not currently working in health occupations, many of them may need additional training in order to perform specific health-related jobs. Nevertheless, a large number of underutilized individuals are recent graduates, speak an official language, have a Canadian education, and may have sufficient skills to provide a source of assistance. In addition, some immigrants might be especially helpful in providing foreign language and cultural assistance to both health care providers and patients.

References

Mahase, E. 2020. “Covid-19: death rate is 0.66% and increases with age, study estimates.” BMJ 2020; 369:m1327 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1327

- Date modified: