Studies on Gender and Intersecting Identities

Functional health difficulties among lesbian, gay and bisexual people in Canada

by Karen Rauh

Skip to text

Text begins

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada.

- From 2017 to 2018 in Canada, age-standardized findings show that a higher share of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people aged 18 and older reported experiencing difficulties in functional health than their heterosexual counterparts. Over half (52.2%) of LGB adults reported experiencing at least some difficulty in any of the six domains of functional health, significantly higher than heterosexual adults (38.3%).

- Among the LGB population, bisexual people (59.6%) were the most likely to report at least some difficulty in one or more functional health domains, followed by gay or lesbian individuals (43.0%).

- Over half of bisexual women (61.6%), bisexual men (56.6%) and lesbian women (50.6%) reported having at least some difficulty in any domain of functional health—significantly higher than heterosexual men (36.6%), heterosexual women (39.9%) and gay men (38.6%).

- Further, when it came to more severe difficulty (i.e., responses of “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all”), age-standardized results show that bisexual women (12.7%) were more likely than heterosexual women (7.3%) and men (5.4%) to report severe difficulty in at least one domain.

- LGB adults, particularly bisexual women, were more likely to report poorer mental health and show a higher prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders than their heterosexual counterparts. Moreover, a larger share of bisexual individuals than heterosexual and gay or lesbian people considered their general health to be fair or poor.

- The role of social determinants of health, such as income, food insecurity, precarious housing, homelessness, violent victimization, discrimination and minority stress, may help explain the higher prevalence of functional difficulties seen among LGB individuals.

Introduction

Functional health difficulties refer to restrictions in an individual's functioning that hinder their ability to perform tasks or activities. These difficulties can affect a person’s work, social and leisure activities, hobbies, sports, and physical activities and limit their full participation in society. Disability is the result of the interaction between a person with a functional difficulty and an unaccommodating environment that makes it harder to function day to day. The impacts can be far reaching. Persons with disabilitiesNote often experience a range of barriers such as income inequality – an important influence over other determinants that can have subsequent effects on the health and well-being of individuals (McDiarmid, 2023). Likewise, mental health-related disabilities can limit a person’s ability to develop or maintain social connections, which play a key role in providing emotional and tangible support (Strautins & McDiarmid, 2023).

The health inequities experienced by the lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) population have been well documented. Research indicates that LGBNote people are more likely to experience poorer mental and physical health outcomes, relative to their heterosexual counterparts (Gilmour, 2019; Tjepkema, 2008; Jaffray, 2020; Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013; King, Semlyen, See Tai, et al., 2008). Studies have documented the higher incidence of functional difficulties and disability among LGB adults, particularly LGB women, among the population in the United States (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim & Barkan, 2012; Cochran, Björkenstam & Mays, 2017). This study addresses an information gap on functional difficulties among people of different sexual orientations in Canada, providing data that can be used to foster a more inclusive society.

This analysis uses Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) data from 2017 to 2018. The first part of this article adds to existing research by examining the health profiles of the LGB and heterosexual populations, disaggregated by gender. The second section of the study presents an analysis of functional difficulties among LGB and heterosexual men and women.

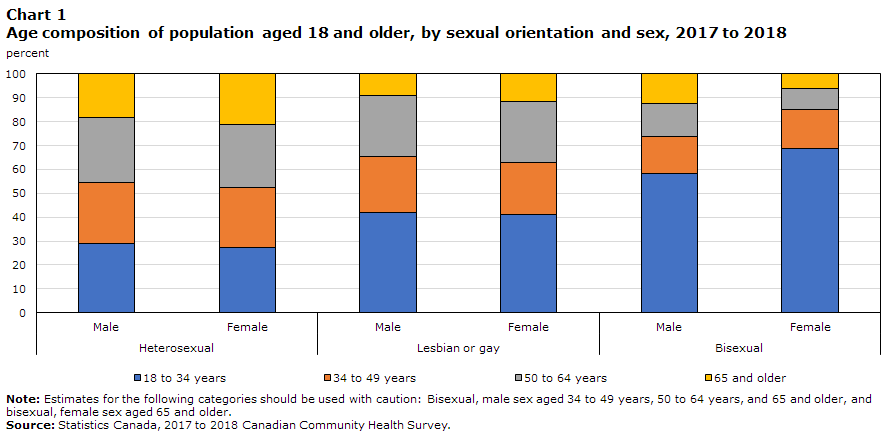

The LGB population—and the bisexual population in particular—is younger, on average, than the heterosexual population (Chart 1). According to CCHS data from 2017 to 2018, the LGB population was concentrated among young adults aged 18 to 34. Specifically, while almost 3 in 10 heterosexual people (28.1%) were young adults, over 4 in 10 gay or lesbian individuals (41.6%) and over 6 in 10 bisexual people (65.0%) were young adults. Among the bisexual population, a higher proportion of bisexual women (68.6%) than bisexual men (58.2%) were aged 18 to 34.Note By contrast, 19.9% of heterosexual people were aged 65 and older—higher than the 10.1% of the gay or lesbian population and 8.4%E of the bisexual population who were older adults.Note This analysis uses age-standardized data to account for the different age structures of the LGB and heterosexual populations and the increased prevalence of functional difficulties among older age groups.

Data table for Chart 1

| Age group | Heterosexual | Lesbian or gay | Bisexual | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| percent | ||||||

| 18 to 34 years | 29.0 | 27.2 | 41.9 | 41.0 | 58.2 | 68.6 |

| 34 to 49 years | 25.5 | 25.1 | 23.3 | 21.8 | 15.7 | 16.6 |

| 50 to 64 years | 27.1 | 26.4 | 25.6 | 25.4 | 13.7 | 8.6 |

| 65 and older | 18.4 | 21.2 | 9.2 | 11.7 | 12.3 | 6.3 |

|

Note: Estimates for the following categories should be used with caution: Bisexual, male sex aged 34 to 49 years, 50 to 64 years, and 65 and older, and bisexual, female sex aged 65 and older. Source: Statistics Canada, 2017 to 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey. |

||||||

Health profile of the lesbian, gay and bisexual population

Previous studies have identified LGB individuals in general, and subgroups of the LGB population in particular, as being at a greater risk of poorer health outcomes, compared with their heterosexual counterparts. Specifically, research indicates that LGB individuals are more likely to be diagnosed with chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, asthma and diabetes, and are at a greater risk for cancer, relative to their heterosexual counterparts (Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013). Minority stressNote is a common explanation for health disparities. Studies suggest that the physical and mental health disparities seen among the LGB population may be linked to stress related to the internalization of negative societal attitudes.

Findings from CCHS data from 2017 to 2018 on the population aged 18 and older are consistent with previous research (Tjepkema, 2008). Age-standardized results suggest that bisexual individuals (20.0%) were twice as likely as heterosexual (10.6%) and gay or lesbian (10.8%) people to consider their general health as being fair or poor.Note

Results were similar when disaggregating self-reported general health by sexual orientation and gender. Table 1 shows that one in five bisexual men (20.0%E) perceived their general health to be fair or poor—about twice the share of heterosexual and gay men (10.0% and 9.1%E, respectively). Similarly, one in five bisexual women (20.0%) reported fair or poor general health—nearly twice the proportion of heterosexual women (11.2%).

| Sexual orientation | Sex | Negative (fair, poor) | Positive (excellent, very good, good) |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| HeterosexualTable 1 Note † | Male | 10.0 | 90.0 |

| Female | 11.2Note ** | 88.8Note ** | |

| Lesbian or gay | Male | 9.1Note E: Use with caution | 90.9 |

| Female | 13.8 | 86.2 | |

| Bisexual | Male | 20.0Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 80.0Note * |

| Female | 20.0Note * | 80.0Note * | |

E use with caution

|

|||

A higher share of LGB individuals consider their mental health to be fair or poor

Past studies indicate that LGB individuals, particularly bisexual women, are much more likely than heterosexual people to report poorer mental health (Gilmour, 2019; Tjepkema, 2008) and be at risk for mental health disorders, suicide ideation and substance abuse (Jaffray, 2020; King, Semlyen, See Tai, et al., 2008). CCHS data from 2017 to 2018 show that a higher proportion of LGB adults (11.4%) indicated that their mental health was fair or poor than their heterosexual counterparts (6.9%). Specifically, bisexual individuals were the most likely of all groups studied to report fair or poor mental health. At 18.9%, bisexual people were almost three times as likely as heterosexual people (6.9%) to report their mental health as being fair or poor. Gay or lesbian individuals were also more likely to report fair or poor mental health (11.4%) than their heterosexual counterparts (6.9%).

The mental health disparity among bisexual people was driven by bisexual women (23.0%), who were the most likely among all groups studied to report negative mental health outcomes (Table 2). Bisexual men (12.8%E) were also more likely than heterosexual men (6.3%) to rate their mental health as fair or poor, and a substantial proportion of lesbian womenNote and gay men also reported fair or poor mental health. Table 2 shows that lesbian women and gay men were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to consider their mental health to be fair or poor.

| Sexual oriention | Sex | Negative (fair, poor) | Positive (excellent, very good, good) |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| HeterosexualTable 2 Note † | Male | 6.3 | 93.7 |

| Female | 7.6Note ** | 92.4Note ** | |

| Lesbian or gay | Male | 10.8Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 89.2Note * |

| Female | 12.4Note * | 87.6Note * | |

| Bisexual | Male | 12.8Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 87.2Note * |

| Female | 23.0Note *** | 77.0Note *** | |

E use with caution

|

|||

LGB men and women are more likely to report having a mood or anxiety disorder than their heterosexual counterparts

The age-standardized results suggest that LGB individuals were more likely to report having mental health disorders, such as mood or anxiety disorders,Note relative to their heterosexual counterparts. Among women aged 18 and older, almost 4 in 10 bisexual women (37.1%) reported having a mood or anxiety disorder, and a larger proportion of lesbian women (27.4%) reported having a mood or anxiety disorder than heterosexual women (16.1%) (Table 3).

Among men, bisexual men (21.0%E) were substantially more likely to report having a mood or anxiety disorder, relative to heterosexual men (8.9%). Gay men (17.3%) were almost twice as likely to report having a mood or anxiety disorder as heterosexual men.

| Sexual orientation | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| HeterosexualTable 3 Note † | 8.9 | 16.1Note ** |

| Lesbian or gay | 17.3Note * | 27.4Note *** |

| Bisexual | 21.0Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 37.1Note *** |

E use with caution

|

||

Lesbian and bisexual women and bisexual men are most likely to report having at least some difficulty in any functional health domain, relative to heterosexual individuals and gay men

The 2017 and 2018 CCHS included questions from the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS), which looks at six functional health domains, including seeing, hearing, mobility (walking or climbing steps), cognition (memory and concentration), self-care and communication (difficulty understanding or being understood when using one’s usual language). The WG-SS asks respondents about their level of difficulty (“no difficulty,” “some difficulty,” “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all”) with the six domains (see Data sources, methods and definitions for more information on the Washington Group measure).

Age-standardized findings show that a higher share of the LGB population reported experiencing difficulties in functional health. Among the population aged 18 and older, just over half (52.2%) of the LGB population reported at least some difficulty (i.e., “some difficulty,” “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all”) in one or more functional health domains—significantly higher than their heterosexual counterparts (38.3%).

Among the LGB population, bisexual people (59.6%) were the most likely to report at least some difficulty in one or more functional health domains. The proportion of gay or lesbian individuals (43.0%) who reported having at least some difficulty in any domain was lower than that of their bisexual counterparts. Heterosexual people (38.3%) were the least likely among all groups to report at least some difficulty in any domain.

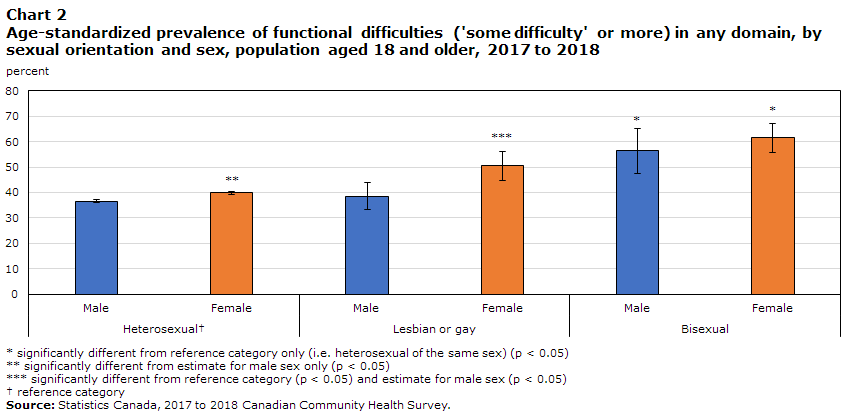

In addition to sexual orientation, the age-adjusted prevalence of functional difficulties varied by gender. Over half of bisexual women (61.6%), bisexual men (56.6%) and lesbian women (50.6%)Note reported having at least some difficulty in any domain of functional health—significantly higher than heterosexual men (36.6%), heterosexual women (39.9%) and gay men (38.6%) (Chart 2). A larger share of heterosexual women than heterosexual men reported having at least some difficulty in one or more domains, while proportions were similar among heterosexual and gay men.

Data table for Chart 2

| Sexual orientation and sex | percent | 95% confidence limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | ||

| HeterosexualData table for chart 2 Note † | |||

| Male | 36.6 | 35.9 | 37.3 |

| Female | 39.9Note ** | 39.2 | 40.6 |

| Lesbian or gay | |||

| Male | 38.6 | 33.4 | 44.0 |

| Female | 50.6Note *** | 44.9 | 56.3 |

| Bisexual | |||

| Male | 56.6Note * | 47.4 | 65.4 |

| Female | 61.6Note * | 55.6 | 67.2 |

|

|||

Bisexual women are more likely than heterosexual women and men to report having more severe difficulty in any functional health domain

The likelihood of reporting more severe difficulty (i.e., “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all”) in one or more domain also varied by sexual orientation and gender. Among the population aged 18 and older, a higher proportion of LGB people (9.1%) reported more severe difficulty, relative to their heterosexual counterparts (6.4%). However, this higher prevalence among LGB people was due to the higher proportion of bisexual women who reported more severe difficulty in at least one functional health domain. Chart 3 shows that bisexual women (12.7%) were more likely than heterosexual women (7.3%) and men (5.4%) to report having more severe difficulty in at least one domain.

Data table for Chart 3

| Sexual orientation and sex | percent | 95% confidence limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | ||

| HeterosexualData table for Chart 3 Note † | |||

| Male | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.7 |

| Female | 7.3Note ** | 7.0 | 7.7 |

| Lesbian or gay | |||

| Male | 7.2Note E: Use with caution | 4.6 | 11.1 |

| Female | 7.7Note E: Use with caution | 5.3 | 11.3 |

| Bisexual | |||

| Male | 7.1Note E: Use with caution | 4.7 | 10.8 |

| Female | 12.7Note * | 9.6 | 16.6 |

E use with caution

|

|||

A closer look at the six domains of functional health (vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, self-care and communication) revealed differences by sexual orientation. In each of the six domains of functional health, a larger share of bisexual adults reported having at least some difficulty, compared with their heterosexual counterparts (Chart 4). Bisexual individuals were also more likely than their gay or lesbian counterparts to report having at least some difficulty in three functional health domains: remembering or concentrating, mobility and self-care. There were no statistically significant differences between gay or lesbian and heterosexual individuals when analyzing the six domains separately.

Data table for Chart 4

| Functional health domain and sexual orientation | percent | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | ||

| HeterosexualData table for Chart 4 Note † | |||

| Seeing | 13.6 | 13.2 | 14.0 |

| Hearing | 11.7 | 11.4 | 12.0 |

| Walking | 14.2 | 13.9 | 14.6 |

| Remembering or concentrating | 16.7 | 16.3 | 17.0 |

| Self-care | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Communicating | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Lesbian or gay | |||

| Seeing | 17.0 | 13.9 | 20.7 |

| Hearing | 11.8 | 9.3 | 14.9 |

| Walking | 15.9 | 13.3 | 18.8 |

| Remembering or concentrating | 18.1 | 15.2 | 21.3 |

| Self-care | 2.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.6 | 4.3 |

| Communicating | 4.2Note E: Use with caution | 3.0 | 6.0 |

| Bisexual | |||

| Seeing | 18.0Note * | 14.5 | 22.2 |

| Hearing | 19.4Note * | 14.6 | 25.3 |

| Walking | 26.5Note * | 21.9 | 31.7 |

| Remembering or concentrating | 30.8Note * | 26.0 | 36.0 |

| Self-care | 8.3Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 5.8 | 11.8 |

| Communicating | 6.3Note * | 4.8 | 8.2 |

E use with caution

|

|||

When the different functional health domains were examined separately, the most notable findings were observed for the cognition domain. Bisexual people were much more likely (30.8%) to report having at least some difficulty remembering or concentrating, relative to their heterosexual (16.7%) and gay or lesbian (18.1%) counterparts. This higher prevalence among the bisexual population was driven by the larger share of bisexual women who reported having at least some difficulty remembering and concentrating, relative to bisexual men.

Chart 5 shows that women were more likely than men of the same sexual orientation to report having at least some difficulty remembering or concentrating. However, a higher proportion of bisexual women reported difficulty in the cognition domain than other groups studied. Nearly 4 in 10 bisexual women (39.5%) reported having at least some difficulty remembering or concentrating — twice the share of bisexual men (17.6%E). One-quarter (25.0%) of lesbian women reported having at least some remembering or concentrating — a higher proportion than that of heterosexual women (18.4%), heterosexual men (14.8%) and gay men (14.1%). No differences were seen among men of different sexual orientations.

Data table for Chart 5

| Sexual orientation and sex | percent | 95% confidence limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | ||

| HeterosexualData table for Chart 5 Note † | |||

| Male | 14.8 | 14.3 | 15.4 |

| Female | 18.4Note ** | 17.9 | 19.0 |

| Lesbian or gay | |||

| Male | 14.1 | 10.9 | 17.9 |

| Female | 25.0Note *** | 20.0 | 30.7 |

| Bisexual | |||

| Male | 17.6Note E: Use with caution | 13.1 | 23.3 |

| Female | 39.5Note *** | 32.5 | 46.9 |

E use with caution

|

|||

The pattern observed for the cognition domain was also seen when examining those reporting more severe difficulty (i.e., “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all”). Bisexual individuals were more likely (5.4%E) to report lot of difficulty remembering or concentrating, compared with heterosexual (1.5%) and gay or lesbian (2.1%E) individuals. Again, this was primarily due to the higher proportion of bisexual women, relative to bisexual men (7.7%E and 2.0%E, respectively), who reported having at least “a lot of difficulty” remembering or concentrating.

The social determinants of health are a specific group of social and economic factors that refer to an individual’s place in society and that have an influence on health. These determinants include, but are not limited to, income, employment and working conditions, physical environments, culture, and social support. The role of social determinants may partially explain the higher prevalence of functional difficulties seen among LGB individuals. Previous research has documented numerous barriers and underlying socioeconomic inequalities that can impact the health of this population. These determinants may interact with each other and have a cumulative effect on the health of individuals. Likewise, the intersection between sexual orientation, gender and functional health difficulties may further expose individuals to vulnerabilities that affect health outcomes.

Income is a key determinant of health and well-being, and challenges stemming from financial hardship are directly related to material aspects of life, such as food insecurity and inadequate housing, that are also known to be related to health and well-being. LGB+ individualsNote are more likely than heterosexual people to report workplace discrimination and barriers to employment and career advancement (Jaffray, 2020; Burczycka, 2021; Brennan, Halpenny, & Pakula, 2022), which may translate into lower earnings. A previous study found that among the employed population aged 25 to 64, heterosexual men had the highest median earnings, followed by gay men and bisexual men. Among women, heterosexual and lesbian women had similar employment incomes, while a significant gap was seen for bisexual women (Statistics Canada, 2022).

Food insecurity has been associated with a range of poor physical and mental health outcomes, such as multiple chronic conditions, distress and depression (Statistics Canada, 2020). LGB individuals are more likely than heterosexual people to live in a household experiencing food insecurity caused by financial constraints. CCHS data from 2015 to 2018 indicate that bisexual people were almost three times more likely than heterosexual people (24.8% versus 8.5%), and nearly twice as likely as gay or lesbian individuals (13.3%), to have lived in food-insecure households in the year preceding the survey (Statistics Canada, 2022).

Experiences of violence can have long-lasting negative effects on physical and mental health and well-being. There is evidence that LGB+ men and women experience higher levels of violent victimization than their heterosexual counterparts. In 2018, bisexual (62.1%) and gay or lesbian (53.4%) individuals were more likely than heterosexual people (36.6%) to have experienced physical or sexual violence, excluding intimate partner violence, at some point in their lives (Jaffray, 2020). In terms of intimate partner violence, a higher share of lesbian and bisexual women (66.8%) than heterosexual women (43.8%) indicated that they had experienced at least one type of intimate partner violence in their lifetime (Jaffray, 2021a). LGB+ men were also more likely than heterosexual men to report being a victim of intimate partner violence (Jaffray, 2021b). While there is a higher prevalence of health risk behaviours among the LGB+ population than the heterosexual population, research suggests that behaviours such as alcohol or drug use among the LGB+ population may reflect a coping mechanism following violent victimization (Jaffray, 2020; Weber, 2008).

Moreover, research suggests that LGB+ individuals, particularly LGB+ women, are at increased risk of experiencing homelessness. A recent study found that LGB+ women were more likely (7.6%) to have experienced at least one episode of unsheltered homelessnessNote at some point in their lives compared with LGB+ men (2.7%), and heterosexual men (2.6%) and women (2.0%) (Uppal, 2022). While experiences of hidden homelessnessNote were more prevalent among both LGB+ men and women than their heterosexual counterparts, LGB+ women were most likely among all groups to have experienced hidden homelessness. The need to leave an abusive or violent situation can lead to temporary homelessness, and rejection from the family home could increase the risk of homelessness for LGB+ youth.

Research also suggests that access to adequate housing is more precarious among the LGB+ population. An analysis found that in 2018, households where the reference person was LGB+ experienced higher rates of core housing needNote and unaffordability, compared with households where the reference person was heterosexual (Randle, Hu, & Thurston, 2021).

Discrimination and social exclusion can also have an impact on physical and mental health. The minority stress framework identifies stigma, prejudice and discrimination among the unique stressors contributing to the poorer mental health outcomes seen among the LGB population (Meyer, 2003). Studies suggest that there is a link between minority stress and LGB health disparities (Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013). However, less is known about the role of minority stress among the bisexual population in particular. Contributing factors thought to be related to the poorer mental health outcomes seen among the bisexual population include discrimination by monosexual (heterosexual, gay and lesbian) individuals, the invisibility of bisexuality in society and the lack of a community that provides bisexual-affirmative support (Ross, Salway, Tarasoff, et al., 2017).

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the differences in functional health reported by men and women of different sexual orientations. Understanding the challenges and barriers that some LGB individuals may experience in their daily lives is an important step toward creating a more equitable and inclusive society. The age-standardized findings show that a higher share of LGB adults reported experiencing difficulties in functional health than their heterosexual counterparts. Further disaggregation revealed that bisexual people were the most likely among all groups studied to report at least some difficulty in one or more functional health domains, followed by gay or lesbian individuals.

The age-adjusted prevalence of functional difficulties varied by both sexual orientation and gender. Bisexual women, bisexual men and lesbian women were significantly more likely than other groups studied to report having at least some difficulty in any functional health domain. Moreover, the likelihood of reporting more severe difficulty in any functional health domain was higher for bisexual women than for heterosexual men and women.

This study also found differences when examining the six different functional health domains separately. For each functional health domain, bisexual people were more likely than heterosexual people to report at least some difficulty. In the cognition domain, women were more likely to report having some difficulty remembering or concentrating than men of the same sexual orientation. However, a substantially higher proportion of bisexual women reported having at least some difficulty remembering or concentrating than all other groups studied.

In terms of the health profile of LGB adults, results were consistent with previous research indicating that LGB people, particularly bisexual women, were more likely to report poorer mental health and show a higher prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders than their heterosexual counterparts. Moreover, a larger share of bisexual individuals than heterosexual and gay or lesbian people considered their general health to be fair or poor.

While this study did not examine the factors associated with functional difficulties, previous research suggests that LGB individuals are more likely to experience income or food insecurity, violent victimization, precarious housing, homelessness, discrimination, and social exclusion. These social determinants may play a role as causes or impacts of the functional difficulties seen among LGB people. Future work could examine the experiences of LGB people with functional health difficulties and disabilities.

Data sources, methods and definitions

Data

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) covers the population aged 12 years and older living in all provinces and territories. Excluded from the sampling frame are individuals living in First Nations communities (on reserve), institutional residents, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and residents of certain remote regions. The CCHS covers approximately 98% of the Canadian population aged 12 and older.

With a sample of 130,000 respondents every two years, it is a well-suited data source for research on smaller populations, such as lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people living in Canada. To increase the sample size for this small population, this release presents pooled data from CCHS 2017 and 2018 cycles.

The Washington Group (WG) on Disability Statistics was established by the United Nations to address the need for cross-nationally comparable statistics on disability and to address equalization of opportunities. The 6-item Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) asks respondents about their level of difficulty (no difficulty, some difficulty, a lot of difficulty, cannot do at all) with the following activities: seeing, even if wearing glasses; hearing, even if using a hearing aid; walking or climbing steps; remembering or concentrating; self-care (e.g. difficulty washing all over or dressing); and communicating when using their usual language (e.g. difficulty understanding or being understood). The WG-SS does not represent all functional difficulties and does not directly address mental health functioning; however, it is designed to cover the most commonly occurring difficulties. CCHS content is comprised of different modules focused on a particular theme of health, some of which are only asked periodically. The most recent WG-SS module data available is for the 2017 and 2018 CCHS cycles.

Measures

This study examines sexual orientation data and does not report results specific to transgender and non-binary people. In 2019, the CCHS began collecting data on both self-reported sex at birth and gender identity, which are required to identify the transgender and non-binary population. Prior to 2019, the CCHS only collected information on the sex of respondents (male or female), as recorded by the interviewer. Although sex and gender refer to two different concepts, the terminology related to gender is used throughout this article to make it easier for readers.

Data on sexual orientation were collected using three response category options with the following definitions: heterosexual (sexual relations with people of the opposite sex); homosexual, that is lesbian or gay (sexual relations with people of your own sex); and bisexual (sexual relations with people of both sexes). In 2019 and subsequent cycles of the CCHS, the definitional text is omitted from these categories, and an additional write-in category is included for respondents to specify a sexual orientation.

Age standardization was conducted to account for the different age structures of the heterosexual and LGB populations.

Click the link for additional information about CCHS data quality and methodology.

References

Brennan, K., Halpenny, C., & Pakula, B. 2022. LGBTQ2S+ voices in employment: Labour market experiences of sexual and gender minorities in Canada. Ottawa: Social Research and Demonstration Corporation. (https://srdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/wage-phase-3-final-report.pdf)

Burczycka, M. 2021. Workers’ experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, sexual assault and gender-based discrimination in the Canadian provinces, 2020. Juristat (Catalogue No. 85-002-X202100100015). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00015-eng.htm)

Cochran, S. D., Björkenstam, C., & Mays, V. M. 2017. Sexual orientation differences in functional limitations, disability, and mental health services use: Results from the 2013–2014 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12). (https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000243)

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K., Kim, H., & Barkan, S. E. 2012. Disability among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Disparities in prevalence and risk. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1). (https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300379)

Gilmour, H. 2019. Sexual orientation and complete mental health. Health Reports (Catalogue No. 82-003-X). (https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x201901100001-eng)

Jaffray, B. 2020. Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018. Juristat (Catalogue No. 85-002-X). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00009-eng.htm)

Jaffray, B. 2021a. Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority women in Canada, 2018. Juristat (Catalogue No. 85-002-X). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00005-eng.htm)

Jaffray, B. 2021b. Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority men in Canada, 2018. Juristat (Catalogue No. 85-002-X). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00004-eng.htm)

King, M., Semlyen, S., See Tai, S., et al. 2008. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8(70). (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-244X-8-70)

Lick, D. J., Durso, L. E., & Johnson, K. L. 2013. Minority Stress and Physical Health Among Sexual Minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science,8(5), 521–548. (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1745691613497965)

McDiarmid, C. 2023. Earnings

pay gap among persons with and without disabilities, 2019. Reports on

Disability and Accessibility in Canada (Catalogue No. 89-654-X). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-654-x/89-654-

x2023002-eng.htm)

Meyer, I. H. 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 2003; 129(5). (DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674)

Randle, J., Hu, Z., & Thurston, Z. 2021. Housing experiences in Canada: LGBTQ2+ people in 2018. Housing Statistics in Canada. Catalogue No. 46-28-0001. (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/46-28-0001/2021001/article/00004-eng.htm)

Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., et al. 2017. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research 2018; 54(4-5). (https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755)

Statistics Canada, 2020. Household food insecurity, 2017/2018. Health Fact Sheets. Catalogue No. 82-625-X. (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2020001/article/00001-eng.htm)

Statistics Canada, 2022. Labour and economic characteristics of lesbian, gay and bisexual people in Canada. Just the Facts. Catalogue No. 89-28-0001. (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-28-0001/2022001/ article/00003-eng.htm)

Strautins, Y., & McDiarmid, C. 2023. Social connections among persons with and without mental health-related disabilities, 2020. Reports on Disability and Accessibility in Canada (Catalogue No. 89-654-X).

Tjepkema, M. 2008. Health care use among gay, lesbian and bisexual Canadians. Health Reports (Catalogue No. 82-003-X). (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2008001/article/10532-eng.pdf)

Uppal, S. 2022. A portrait of Canadians who have been homeless. Insights on Canadian Society. Catalogue No. 75-006-X. (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2022001/article/00002-eng.htm)

Weber, G. N. 2008. Using to numb the pain: Substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30(1). (https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.30.1.2585916185422570)

- Date modified: