Economic and Social Reports

Immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada by province of residence

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202300600003-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

Using the 2020 General Social Survey, this study shows that the likelihood of reporting a very strong sense of belonging to Canada is higher for immigrants in Ontario and Atlantic Canada and lower for immigrants in British Columbia and Alberta. Once regional differences in the sociodemographic composition of the immigrant population, perceived discrimination and structural conditions were controlled for, the difference in sense of belonging to Canada between immigrants in Alberta and Ontario disappeared. In contrast, after these factors were controlled for, there was still a large difference between immigrants in Ontario and British Columbia. This difference is attributable to the especially strong sense of belonging to Canada among immigrants in Ontario.

Authors

Max Stick and Christoph Schimmele are with the Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, at Statistics Canada. Maciej Karpinski and Seyba Cissokho are with the Policy Research Division at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in collaboration with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The authors thank Chris Hamilton, Feng Hou, Filsan Hujaleh, Lisa Kaida, Allison Leanage, Grant Schellenberg and Martin Turcotte for their advice and comments on an earlier version of this article.

Introduction

Sense of belonging to Canada is a well-documented measure of social integration, and it also correlates with subjective well-being (Berry & Hou, 2016; Bilodeau et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2012). Sense of belonging is an indicator of national identification and a feeling that one is accepted and “at home” in Canada (Wu et al., 2011). Immigrants form their sense of belonging to Canada based on their post-migration experiences, especially their perceptions of acceptance and opportunities for success in the receiving country (Hou et al., 2018; White et al., 2015).

In the 2003 and 2013 cycles of the General Social Survey (GSS), proportionally larger numbers of immigrants than Canadian-born people reported a very strong sense of belonging to Canada, the highest rating on the scale (Schellenberg, 2004; Statistics Canada, 2015). This difference is partly attributable to immigrants’ stronger sense of belonging derived from Canada’s multicultural policies (Pearce, 2008) and a relatively lower sense of belonging to Canada among Canadian-born people in Quebec (Berry & Hou, 2020). Other research has found that immigrants are also more likely than Canadian-born people to believe that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, multiculturalism, and national symbols (e.g., the Canadian flag) are important aspects of Canadian identity (Adams & Parkin, 2022).

However, the strength of immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada differs by sociodemographic characteristics such as years since immigration, age at immigration, admission category and population group (Berry & Hou, 2016; Painter, 2013; Schellenberg, 2004). Immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada also varies across geographic areas such as neighbourhoods (Wu et al., 2011) and different-sized metropolitan areas (Kitchen, Williams, & Gallina, 2015), and between Quebec and other provinces because of different integration policies (Berry & Hou, 2020).

This study examines whether immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada depends on their province of residence. The majority of immigrants reside in Quebec, Ontario or British Columbia, but immigrants have become more dispersed across the provinces over the last two decades (Bonikowska et al., 2015; Vézina & Houle, 2017). Long-term differences in the settlement patterns of immigrants have contributed to differences in the sociodemographic composition of the immigrant population in each province. For reasons discussed below, these compositional differences may have implications for cross-provincial variation in immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada.

First, the provinces differ on the shares of recent immigrants that compose their immigrant populations. In 2021, the share of recent immigrants ranged from 14% of immigrants in British Columbia and Ontario to 30% (or more) of immigrants residing in Saskatchewan and the Atlantic provinces.Note This compositional difference may contribute to cross-provincial variation because sense of belonging to Canada is weaker among recent immigrants than among longer-term immigrants (Gilkinson & Sauvé, 2010; Schellenberg, 2004; Wu & So, 2020). This implies that immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada may be stronger in the provinces (e.g., Ontario) that have larger shares of longer-term immigrants than recent ones. However, even with increasing years in Canada, “racially distinct minorities remain less confident that they fully belong” (Soroka, Johnston & Banting, 2007, p. 584).

Second, the provinces differ with regard to the size of the population groups (e.g., Chinese, South Asian, Black and White) that compose their immigrant populations (Bonikowska et al., 2015; Hou, 2005). This compositional difference may influence cross-provincial variation in the proportion of immigrants with a very strong sense of belonging to Canada because exclusionary experiences (e.g., discrimination) are known to influence immigrants’ national identities and decrease their sense of belonging (Bilodeau et al., Forth.; Reitz & Banerjee, 2007; Schimmele & Wu, 2015). These experiences are not uniform, and how immigrants are received in their communities differs across population groups. For example, sense of belonging has been shown to be weaker among those who are not of British or northern European ancestry (Soroka et al., 2007). Furthermore, discrimination has a stronger negative impact on sense of belonging for racialized groups than for White people (Wu & Finnsdottir, 2021).

Third, provincial differences in the selection of immigrants through special admission programs (e.g., Provincial Nominee Program) may have contributed to differences in the sociodemographic composition of provincial immigrant populations. For example, the recent increase in immigration to the Prairies was largely achieved through the provincial nomination of immigrants and the selection of individuals on the basis of their economic characteristics and local labour market needs (Bonikowska et al., 2015). This may have increased the share of immigrants with certain characteristics (e.g., postsecondary education) and employment opportunities. For many immigrants, “the benchmark of having ‘fully arrived’ in Canadian society (and thus feeling a true sense of belonging) is tied to full-time employment” (Kitchen et al., 2015, p. 15).

Besides these compositional differences, the provinces differ on structural factors such as employment, educational opportunities and economic diversity, which all influence the acculturation and incorporation of immigrants (Hou, 2021; Williams et al., 2015). Immigrants’ sense of belonging is dependent on their prospects to economically contribute to the receiving society and secure material well-being for themselves and their families (Hou, Schellenberg, & Berry, 2018). When faced with constrained opportunities for socioeconomic mobility, immigrants tend to have weaker levels of identification with the receiving society.

This study compares the provinces on the proportion of immigrants with a very strong sense of belonging to Canada. It examines whether the observed variation is attributable to provincial differences in the sociodemographic composition of the immigrant population and structural context. Structural context refers to socioeconomic conditions in the provinces (median household income and percentage of unemployed individuals) and the size of the immigrant population in the provinces.

Data and methods

This study uses data from Statistics Canada’s 2020 GSS. The GSS is an annual, cross-sectional survey that collects information on social trends. Each cycle of the GSS focuses on a specific theme, generally rotating every five to seven years. The 2020 GSS (Cycle 35) focused on social identity. The target population was people aged 15 years and older living in the 10 provinces, excluding full-time residents of institutions and reserves, and included 13,931 landed immigrants. The survey was conducted between August 2020 and February 2021 with a self-completed electronic questionnaire or a computer-assisted telephone interview (Statistics Canada, 2021).

The GSS asked respondents, “How would you describe your sense of belonging to Canada?” Respondents could select either very strong, somewhat strong, somewhat weak, very weak or no opinion. In this article, response categories were collapsed to create a dichotomous variable, with very strong responses coded as 1 and all other responses coded as 0. The predicted probabilities of reporting a very strong sense of belonging to Canada for immigrants across province of residence, the focal independent variable, were estimated from an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model. Although the dependent variable is binary, OLS regression models are presented for ease of interpretation. Logistic regression models were also run, and similar results were found. Because of the small number of respondents, a regional aggregation was used for the Atlantic provinces.

Multivariate analysis was conducted to determine whether provincial differences in sense of belonging to Canada were attributable to compositional and structural factors.Note The composition of the immigrant population in the provinces was measured with individual-level characteristics: years since landing, immigration entry class, age at immigration, population group,Note sex, age group, marital status, logged adult-equivalent adjusted family income, employment status, educational attainment and perceived discrimination. Structural context was measured with variables at the economic region level: logged median adult-equivalent adjusted family income, unemployment rate (in percentage) and percentage of immigrants. These structural variables were drawn from answers to the 2016 Census of Population long-form questionnaire.

All estimates were calculated using survey weights to address the over- or underrepresentation of certain groups, and bootstrap weights were used in the significance tests.

Immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada across provinces, 2020

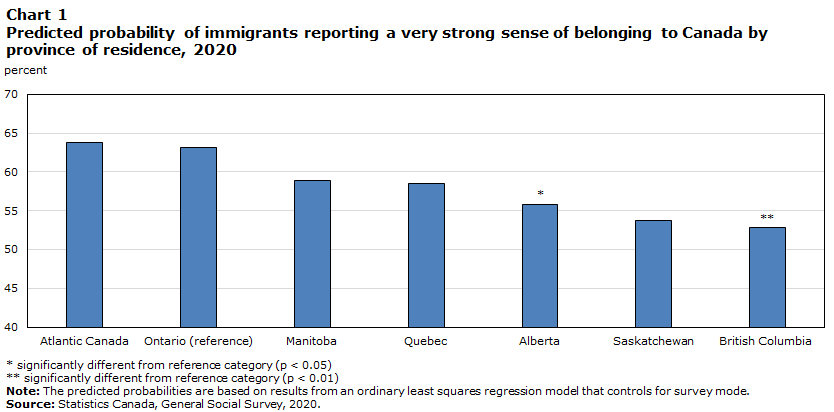

Chart 1 shows the predicted probabilities of reporting a very strong sense of belonging to Canada (versus a somewhat strong and weaker levels of belonging) among immigrants by province (these estimates are based on an OLS regression model, which controls for survey mode). It compares immigrants in Ontario with those in the other provinces. Ontario was selected as the reference province because that is where the majority of immigrants reside.

The predicted probability of reporting a very strong sense of belonging was highest for immigrants in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces, at 63%. This compared with 59% for immigrants in Quebec and Manitoba, 56% for immigrants in Alberta, and 54% for immigrants in Saskatchewan. Immigrants in British Columbia had the lowest probability of reporting a very strong sense of belonging, at 53%.

Only immigrants in Alberta and British Columbia had a significantly lower likelihood of reporting a very strong sense of belonging to Canada compared with immigrants in Ontario. Despite lower predicted probabilities for immigrants in Manitoba, Quebec and Saskatchewan, these estimates were not significantly different from the probability for immigrants in Ontario.

Data table for Chart 1

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| Atlantic Canada | 63.85 |

| Ontario (reference) | 63.19 |

| Manitoba | 58.89 |

| Quebec | 58.52 |

| Alberta* | 55.85 |

| Saskatchewan | 53.79 |

| British Columbia** | 52.77 |

|

* significantly different from reference category (p < 0.05) ** significantly different from reference category (p < 0.01) Note: The predicted probabilities are based on results from an ordinary least squares regression model that controls for survey mode. Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2020. |

|

Table 1 compares provincial differences in the probability of reporting a very strong sense of belonging to Canada, after controlling for the sociodemographic characteristics of immigrants, perceived discrimination and the structural context of economic regions. The difference between immigrants in Alberta and Ontario almost entirely disappears and is statistically non-significant after controlling for these variables. This shows that if the composition of the immigrant population, perceptions of discrimination and structural characteristics in these provinces were the same, immigrants in Alberta would not be less likely than immigrants in Ontario to have a very strong sense of belonging to Canada.

| Coefficient | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| Ontario (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Atlantic provinces | 0.031 |

| Quebec | -0.114Note * |

| Manitoba | -0.084 |

| Saskatchewan | -0.094 |

| Alberta | -0.004 |

| British Columbia | -0.110Note ** |

| Sex | |

| Men (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Women | -0.029 |

| Age group | |

| 15 to 24 years (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| 25 to 54 years | 0.042 |

| 55 years and older | 0.018 |

| Logged AEA family income | -0.010 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Unemployed | -0.072 |

| Not in labour force | 0.027 |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or less (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Some postsecondary education | 0.068Note * |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.046 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or common law (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | -0.023 |

| Never married | -0.069 |

| Population group | |

| White (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Black | 0.108Note * |

| Chinese | -0.177Note *** |

| South Asian | 0.172Note *** |

| Southeast Asian and Filipino | 0.057 |

| Arab and West Asian | 0.170Note *** |

| Latin American | 0.181Note *** |

| Years since landing | |

| 0 to 5 (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| 6 to 9 | 0.102Note * |

| 10 or more | 0.045 |

| Age at immigration | |

| 13 years and older (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| 12 years and younger | 0.051 |

| Immigrant entry class | |

| Economic immigrant (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Family class | -0.004 |

| Refugee | 0.089 |

| Admitted prior to 1980 | 0.141Note *** |

| Discrimination | |

| No (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable |

| Yes | -0.057Note * |

| Logged median AEA family income (ER) | -0.203 |

| Percentage of immigrants (ER) | 0.000 |

| Percentage unemployed (ER) | -0.018 |

| Constant | 2.988 |

... not applicable

Sources: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2020; Census of Population, 2016. |

|

After the addition of covariates, a large and significant difference between immigrants in Ontario and British Columbia remained. This shows that, even after the composition of the immigrant population, perceptions of discrimination and characteristics of the economic region were controlled for, immigrants in British Columbia were about 11 percentage points less likely to report a very strong sense of belonging to Canada than immigrants in Ontario.

In contrast, a significant difference between immigrants in Quebec and Ontario emerged after controlling for these variables. In this model, immigrants in Quebec were 11 percentage points less likely to report a very strong sense of belonging to Canada compared with immigrants in Ontario. This suggests that the structural conditions and the sociodemographic profile of immigrants in Quebec have an effect on whether immigrants express a strong sense of belonging to Canada.

Conclusion

Sense of belonging is associated with immigrants’ quality of life in Canada and their level of social integration (Kitchen, 2015; Wu et al., 2011). This study showed that the strength of immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada varies modestly by province of residence. Generally, sense of belonging to Canada was strongest among immigrants living in Atlantic Canada and Ontario, and weakest among immigrants in British Columbia and Alberta.

The difference in sense of belonging to Canada between immigrants in Alberta and Ontario is attributable to the composition of Alberta’s immigrant population (based on sociodemographic characteristics such as years since landing, population group, age group and education), perceptions of discrimination and differences in structural conditions (unemployment rates, median income and size of the immigrant population) between Alberta and Ontario. If these factors were equal, the proportion of immigrants in Alberta who reported a very strong sense of belonging to Canada would be similar to that in Ontario.

The difference between immigrants in Ontario and British Columbia was not explained by these sociodemographic characteristics, perceived discrimination or structural factors. Even net of these factors, immigrants in Ontario were more likely to report a very strong sense of belonging to Canada than immigrants in British Columbia. However, immigrants in Ontario were also more likely to report this outcome compared with Canadian-born people in Ontario (results not shown). Conversely, there was little difference in sense of belonging to Canada between immigrants and Canadian-born people in British Columbia.

Taken together, this evidence shows that immigrants in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces have especially favourable views about belonging to Canada.

References

Adams, M., & Parkin, A. (2022). The Evolution of Canadian Identity. Toronto: Environics Institute for Survey Research.

Berry, J. W., & Hou, F. (2016). Immigrant acculturation and wellbeing in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 57(4), 254–264.

Berry, J. W., & Hou, F. (2020). Immigrant acculturation and wellbeing across generations and settlement contexts in Canada. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(1–2), 140–153.

Bilodeau, A., White, S. E., Turgeon, L., & Henderson, A. (2020). Feeling attached and feeling accepted: Implications for political inclusion among visible minority immigrants in Canada. International Migration, 58(2), 272–288.

Bilodeau, A., White, S. E., Turgeon, L., & Henderson, A. (Forth.). Ethnic minority belonging in a multilevel political community: The role of exclusionary experiences and welcoming provincial contexts in Canada. Territory, Politics, Governance. Published online June 30, 2022. doi:10.1080/21622671.2022.2080758.

Bonikowska, A., Hou, F., & Picot, G. (2015). Changes in the regional distribution of new immigrants to Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Catalogue no. 11F0019M – No. 366. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Gilkinson, T., & Sauvé, G. (2010). Recent immigrants, earlier immigrants, and the Canadian-born: Association with collective identities. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

Hou, F. (2005). The initial destinations and redistribution of Canada’s major immigrant groups: Changes over the past two decades. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE – No. 254. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Hou, F. (2021). The resettlement of Vietnamese refugees across Canada over three decades. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(21), 4817–4834.

Hou, F., Schellenberg, G., & Berry, J. W. (2018). Patterns and determinants of immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada and their source country. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(9), 1612–1631.

Hou, F., & Schimmele, C. (2022). How Survey Mode and Survey Context Affect the Measurement of Self-Perceived Racial Discrimination across Cycles of the General Social Survey. Analytical Studies: Methods and References. Catalogue no. 11-633-X – No. 043. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Kitchen, P., Williams, A. M., & Gallina, M. (2015). Sense of belonging to local community in small-to-medium sized Canadian urban areas: A comparison of immigrant and Canadian-born residents. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 1–17.

Painter, C. V. (2013). Sense of belonging: Literature review. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

Pearce, P. (2008). Bridging, bonding, and trusting: The influence of social capital and trust on immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada. Atlantic Metropolis Centre – Working Paper Series. Working Paper No. 18.

Reitz, J. G., & Banerjee, R. (2007). Racial inequality, social cohesion, and policy issues in Canada. In K. Banting, T. J. Courchene, & F. L. Seidle, (Eds.). Belonging? Diversity, recognition and shared citizenship in Canada (pp. 489–545). Montréal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Schellenberg, G. (2004). 2003 General Social Survey on Social Engagement, cycle 17: An overview of findings. Catalogue no. 89-598-XIE. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Schimmele, C., & Wu, Z. (2015). The new immigration and ethnic identity. Population Change and Lifecourse Strategic Knowledge Cluster Paper Series. Volume. 3, Issue 1, Article 1.

Soroka, S., Johnston, R., & Banting, K. (2007). Ties that bind? Social cohesion and diversity in Canada. In K. Banting, T. J. Courchene, & F. L. Seidle, (Eds.). Belonging? Diversity, recognition and shared citizenship in Canada (pp. 561–600). Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Sense of belonging to Canada, the province of residence and the local community. Catalogue no. 89-652-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2021). General Social Survey – Social Identity. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada (2022). Table 98-10-0308-01 Visible minority by immigrant status and period of immigration: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts [Data Table]. https://doi.org/10.25318/9810030801-eng

Vézina, M., & Houle, M. (2017). Settlement patterns and social integration of the population with an immigrant background in the Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver metropolitan areas. Catalogue no. 89-657-X2016002. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

White, S., Bilodeau, A., & Nevitte, N. (2015). Earning their support: Feelings toward Canada among recent immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(2), 292–308.

Williams, A. M., Kitchen, P., Randall, J., Muhajarine, N., Newbold, B., Gallina, M., & Wilson, K. (2015). Immigrants’ perceptions of quality of life in three second- or third-tier Canadian cities. The Canadian Geographer, 59(4), 489–503.

Wu, Z., & Finnsdottir, M. (2021). Perceived racial and cultural discrimination and sense of belonging in Canadian society. Canadian Review of Sociology, 58(2), 229–249.

Wu, Z., Hou, F., & Schimmele, C. (2011). Racial diversity and sense of belonging in urban neighborhoods. City and Community, 10(4), 373–392.

Wu, Z., Schimmele, C., & Hou, F. (2012). Self-perceived integration of immigrants and their children. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 53(9), 1689–1699.

Wu, Z., & So, V. W. Y. (2020). Ethnic and national sense of belonging in Canadian society. International Migration, 58(2), 233–245.

- Date modified: