Economic and Social Reports

Immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada: Highlights from recent studies

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100900001-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

This paper highlights the main findings of the Immigrant Entrepreneurs Research Program initiated by the Research and Evaluation Branch of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and Statistics Canada.

Who are immigrant entrepreneurs?

The definition of an immigrant entrepreneur varies from study to study, but here the term “entrepreneur” is used synonymously with “business owner.” Unless otherwise noted, these studies focus on two categories of immigrant entrepreneurs:

- Owners of incorporated private companies with employees: Private incorporated companies are generally small and account for about 55% of employment in the private sector. Publicly owned incorporated companies are excluded from the analysis because (i) their ownership is widely dispersed and (ii) their shareholders are usually not involved in the operations of the firm and are not entrepreneurs in any meaningful sense.

- The unincorporated primarily self-employed: There is little economic activity associated with much of the unincorporated self-employment in Canada. Here, the focus is on the “primarily” self-employed, those whose earnings from self-employment exceed those from paid work. They represent roughly half of all unincorporated self-employed individuals. One notable exception is the study on gig work, which focuses specifically on minor self-employment activities.

Business ownership and self-employment rates are generally higher among immigrants than the Canadian-born population

- In 2016, 11.9% of immigrants aged 25 to 69 years owned either a private incorporated company or were primarily self-employed, compared with 10.1% of the second generation (individuals born in Canada with an immigrant parent) and 8.4% of “third plus” generations (a category consisting of all Canadian-born individuals with both Canadian-born parents).

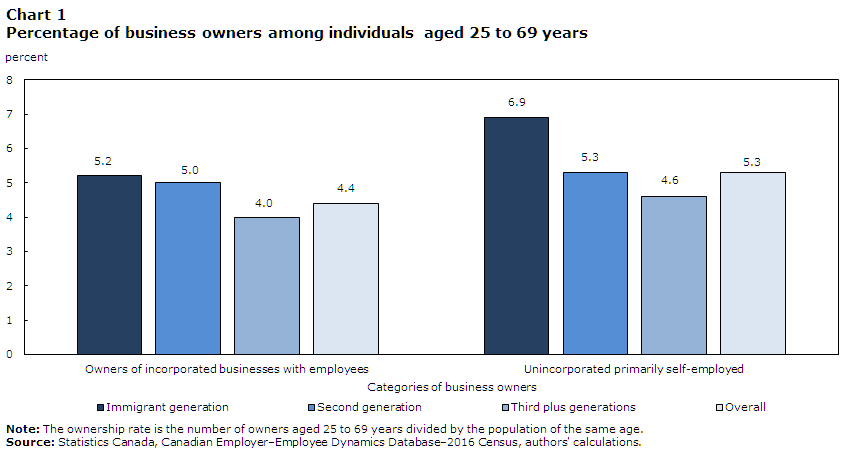

- The difference between immigrants and the other generations was largely related to higher rates of primary self-employment among immigrants, which were 6.9% for immigrants, 5.3% among the second generation and 4.6% of third plus generations (Chart 1).

- Earlier research showed that the higher self-employment rate among immigrants was caused, at least in part, by the difficulty of finding suitable paid employment.

- About 5.2% of immigrants owned a private incorporated business with employees in 2016, compared with 5.0% of the second generation and 4.0% of third plus generations (Chart 1).

- Immigrant-owned firms are usually smaller than those owned by Canadian-born owners.

Data table for Chart 1

| Categories of business owners | Immigrant generation | Second generation | Third plus generations | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Owners of incorporated businesses with employees | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.4 |

| Unincorporated primarily self-employed | 6.9 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 5.3 |

|

Note: The ownership rate is the number of owners, aged 25 to 69, divided by the population of the same age. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database–2016 Census, authors' calculations. |

||||

The propensity to be a business owner varies according to immigrants’ characteristics

- Immigrant men are about twice as likely to own a business as immigrant women.

- Immigrants in the 45-to-54 age range are more likely to own a private incorporated business than immigrants in other age groups. (This is also true for Canadian-born owners.)

- The propensity to own a private incorporated company generally increases with level of education, while the opposite is true for the propensity to be primarily self-employed.

- The percentage of owners who are science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) graduates is considerably higher among immigrant business owners than among business owners from the second generation and third plus generations (Chart 2).

- The business ownership rate is lower among recent immigrants but it increases with years in Canada.

- Ownership rates for private incorporated businesses are similar across most source regions, with the exception of immigrants from Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa who generally have lower ownership rates.

Data table for Chart 2

| Categories of business owners | Immigrant generation | Second generation | Third plus generations |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| All individuals aged 25 to 69 years | 18.4 | 11.5 | 8.7 |

| Owners of incorporated businesses with employees | 22.1 | 12.3 | 10.0 |

| Unincorporated primarily self-employed | 14.6 | 8.2 | 6.1 |

|

Note: Not all science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates are university degree holders; college degrees are included. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database–2016 Census, authors' calculations. |

|||

Immigrant entrepreneurs come from all admission categories

- Four broad admission categories of immigrants are considered here: the economic class (excluding the business class),Note business class, family class and refugees.

- Business class immigrants are most likely to own a private incorporated business, but this is a small class that accounts for about 10% of all immigrant-owned firms.

- Among other admission categories, economic-class principal applicants are more likely than other immigrants to be incorporated firm owners.

- Refugees are more likely to be unincorporated self-employed than the economic class and the Canadian-born population, perhaps related to labour market difficulties.

- Economic class immigrants are the largest single group of immigrant business owners, accounting for over 40% of all immigrant-owned businesses.

The main difference between economic class and family class or refugee business owners is not their propensity to own a business, but the type of the business they own

- Economic class immigrants are more likely than the family class and refugees to own a private incorporated company.

- Refugees are more likely than economic class and Canadian-born entrepreneurs to be unincorporated self-employed.

- Refugee entrepreneurs are concentrated in ground transportation (e.g., trucking, taxi services), retail trade, food services and services to dwellings (e.g., janitors).

- Economic class immigrants are about twice as likely as the Canadian-born population to own a company in the knowledge-based industries, notably in architecture and engineering services, computer systems design, and management and scientific consulting.

- Very few business class immigrants own companies in knowledge-based industries.

After becoming business owners, immigrants generally remain in business about as long as Canadian-born owners

- Roughly 80% of immigrant owners of private companies were still in business two years after becoming owners and 58% after seven years. The survival rates were similar for Canadian-born owners.

- Recent immigrants (those in Canada for less than 10 years) had higher exit rates from ownership and shorter durations than the Canadian-born population or longer-term immigrants.

- The duration of business ownership varied with immigrants’ characteristics and the industry of the business.

Immigrant-owned firms tend to be younger than firms owned by those born in Canada, and younger firms generally create jobs at a higher rate than older firms

- A study found that from 2003 to 2013, net job creation was higher among immigrant-owned firms than those of Canadian-born individuals. They accounted for 25% of the net jobs created, while representing 17% of the private incorporated firms studied.

- This difference was primarily because of immigrant-owned firms being younger. After adjusting for differences in firm age, firm size and other characteristics, there was no difference in the net job creation between firms owned by immigrants and those owned by Canadian-born individuals.

Product and process innovation is marginally higher in firms owned by immigrants than in other firms

- Based on self-reported data and after accounting for differences in firm and owner characteristics, a marginally higher percentage of immigrant-owned, small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) implemented a product innovation over a three-year period. This was at 29%, compared with 27% among Canadian-born SME owners. The corresponding rates for a process innovation were 21% and 17%.

- Use of intellectual property (registered trademarks, patents, etc.) by immigrant-owned firms was similar to that of firms owned by the Canadian-born population.

Immigrants and the Canadian-born population finance their businesses in similar ways

- There is little evidence to suggest that access to financing is more of an issue for immigrant owners of SMEs than for Canadian-born owners of such firms.

- After adjusting results for differences in the characteristics of

the firms owned by immigrants and Canadian-born individuals

- firms owned by immigrants were only marginally less likely to apply for ongoing financing than firms owned by the Canadian-born population

- all firms turned more often to debt financing than equity financing

- there was little difference in the sources of financing

- applications for financing made by immigrants were fully approved as often as those submitted by Canadian-born owners.

- Personal financing was the most commonly used source of start-up financing by both immigrant and Canadian-born entrepreneurs.

- Recent immigrants were less likely to turn to a formal financial institution, such as a bank, for start-up financing.

- Interestingly, both immigrant and Canadian-born SME owners indicated that access to financing was the least important of many obstacles to growth.

The prevalence of being an unincorporated self-employed “gig” worker (e.g., freelancer or an on-demand worker) is higher among immigrants

- An estimated 10.8% of all male immigrant workers who have been in Canada for less than five years participated in the “gig economy” in 2016, compared with 6.1% of male Canadian-born workers.

Concluding remarks

Many studies find that business ownership rates are generally higher among immigrants than among the native-born population, in this case the Canadian-born population. There are many possible reasons for this outcome. Immigrants, particularly refugees and the family class, have more difficulty locating suitable paid employment than the Canadian-born population and are more likely to turn to self-employment as a result. Differences in background characteristics can also be important. For example, economic immigrants are more highly educated and this can increase their tendency to own a private incorporated company. Other possible reasons include being part of immigrant networks and better able to serve the needs of immigrant communities, and benefiting from the collective business experience accumulated in various immigrant communities. Comparisons between immigrant and Canadian-born business owners also suggest that, in many ways, their entrepreneurial activities are similar: they finance their firms in similar ways, their businesses survive for a similar period of time and their job creation rates are similar after adjusting for other differences. The studies also highlighted some dissimilarities. The marginally higher innovation rates reported by immigrant business owners and the higher propensity among economic immigrants to own a knowledge-based company are possibly related to the higher rates of STEM education among economic class immigrants. However, the use of intellectual property (registered trademarks, patents, etc.) by immigrant-owned firms is similar to that of firms owned by the Canadian-born population. Refugees and family class immigrants are also more likely to have a business in ‘traditional’ immigrant industries (e.g., transportation, retail trade, accommodation and food services) than both economic class immigrants and the Canadian-born population.

Authors

Garnett Picot works with the Research and Evaluation Branch at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Yuri Ostrovsky works in the Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch at Statistics Canada.

Further reading

Abada, T., F. Hou, and Y. Lu. 2014. “Choice or necessity: Do immigrants and their children choose self-employment for the same reasons?” Work, Employment and Society 28 (1): 78–94.

Green, D., H. Liu, Y. Ostrovsky, and G. Picot. 2016. Immigration, Business Ownership and Employment in Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 375. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Hou, F., and S. Wang. 2011. “Immigrants in self-employment.” Perspectives on Labour and Income 23 (3): 5–16.

Jeon, S.-H., H. Liu, and Y. Ostrovsky. 2019. Measuring the Size of the Gig Economy in Canada Using Administrative Data. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 437. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Ostrovsky, Y., and G. Picot. 2020. “Innovation in immigrant-owned firms.” Small Business Economics 1–18.

Ostrovsky, Y., and G. Picot. 2018. The Exit and Survival Patterns of Immigrant Entrepreneurs: The Case of Private Incorporated Companies. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 401. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Ostrovsky, Y., G. Picot, and D. Leung. 2019. “The financing of immigrant-owned firms in Canada.” Small Business Economics 52 (1): 303–317.

Picot, G., and F. Hou. 2019. Skill Utilization and Earnings of STEM-educated Immigrants in Canada: Differences by Degree Level and Field of Study. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 435. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Picot, G., and Y. Ostrovsky. 2017. Immigrant Businesses in Knowledge-based Industries. Economic Insights, no. 69. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-626-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Picot, G., and Y. Ostrovsky. 2021. “Immigrant and Second-generation Entrepreneurs in Canada: An Intergenerational Comparison of Business Ownership.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (9). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

Picot, G., and A.-M. Rollin. 2019. Immigrant Entrepreneurs as Job Creators: The Case of Canadian Private Incorporated Companies. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 423. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Date modified: