Economic and Social Reports

Gender differences in early career job mobility and wage growth in Canada

by Zechuan Deng

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100100002-eng

Abstract

This Insights article discusses the main differences by gender in early career job mobility for young workers in Canada, and the potential impact of these differences on wage growth over the first 10 years of a worker’s career. The study is based on two data sources that can inform researchers on differences by gender in early career job mobility for young workers and the associated impact on wage growth. The population of interest for this study consists of employed individuals aged 25 to 34 in 2005 since individuals within this age group are more likely to be out of school and working full-time.

Author

Zechuan Deng is with the Strategic Analysis, Publications and Training Division, Analytical Studies Branch, at Statistics Canada.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the Department for Women and Gender Equality.

Introduction

Over the past decades, more and more women have left their traditional full-time homemaker roles to enter the labour force and acquire full-time or part-time paying jobs (UN Women 2017). While women have made great strides in the labour market in terms of labour market participation, they still have not caught up to men in terms of wages. In Canada, the gender gap in hourly wages among employees aged 25 to 54 was 13.3% in 2018, and more than two-thirds of this gap was unexplained by standard explanatory factors such as education, job attributes, occupation and industry, and demographics (Pelletier, Patterson and Moyser 2019). This points to a continued need for analysis in this area to better understand gender-based wage disparity.

Previous studies have shown that the gender wage gap is relatively minor when workers enter the labour market, but that it widens quickly over the first 5 to 10 years of an individual’s career (Manning and Swaffield 2008). This highlights the importance of examining the differences in early career job mobility, including the type of job separation (i.e., temporary separation vs. permanent separation) and the reason for the separation. In addition, according to studies by Hirsch and Schnabel (2012) and Eryar and Tekgüç (2014) based on European labour markets, men were more likely than women to make a job-to-job move (i.e., to switch employers), while women were more likely to go from employment to unemployment, typically for maternity leave.

The situation in Canada remains mostly unclear because of the lack of relevant studies. To fill this gap, this article discusses the main differences by gender in early career job mobility for young workers (aged 25 to 34) in Canada, and the potential impact of these differences on wage growth over the first 10 years of a worker’s career (between 2005 and 2015).

This study is based on two data sources that can inform researchers on differences by gender in early career job mobility for young workers, and the impact of these differences on wage growth.Note First, the 2019 Longitudinal Worker File (LWF) contains information on job mobility, including the type of job separation (temporary vs. permanent) and the reason for the separation (e.g., layoffs, quitting), for the same individual between 1989 and 2016.Note For simplicity, only the main job, which is defined as the job where an individual had the highest employment income according to the LWF file in a given year, is kept.Note Second, data from the 2006 and 2016 Census of Population long-form questionnaires provide a snapshot of key information, such as weeks worked, that is not available in the LWF.Note The population of interest for this study consists of employed individuals aged 25 to 34 in 2005 since individuals in this age group are more likely to be out of school and working full-time.Note

Overall, women were slightly less likely than men to experience a job separation

Overall, women were less likely than men to experience a job separation, though the difference was small (Chart 1). A job separation is defined as a separation from the employer, regardless of whether the employee returns to the employer during the year of the separation or in the following year. In general, there is a decreasing trend on job separation over time for both women and men. This is consistent with previous studies based on the American labour market that show that older workers are less likely than younger workers to experience job transitions (Haltiwanger, Hyatt and McEntarfer 2018).

Data table for Chart 1

| Female workers | Male workers | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 2005 | 23.1 | 23.8 |

| 2006 | 23.5 | 23.2 |

| 2007 | 22.2 | 22.6 |

| 2008 | 19.4 | 19.6 |

| 2009 | 17.7 | 18.7 |

| 2010 | 17.2 | 18.2 |

| 2011 | 16.4 | 17.3 |

| 2012 | 15.4 | 16.0 |

| 2013 | 14.5 | 15.3 |

| 2014 | 14.4 | 15.2 |

| 2015 | 13.6 | 14.6 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. | ||

Permanent job separations

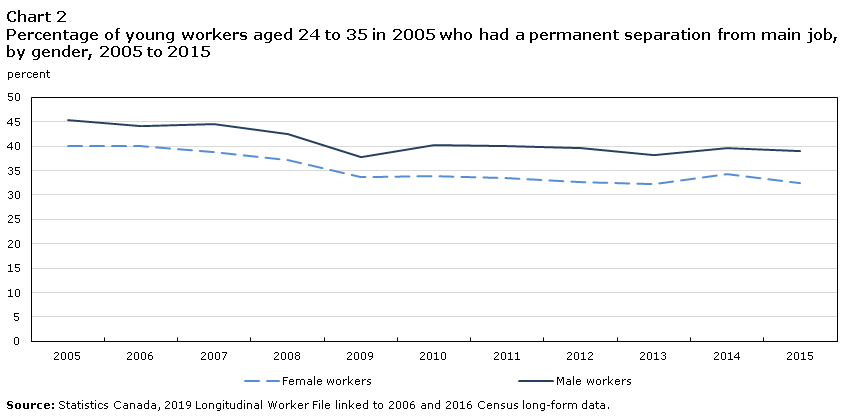

Women were less likely than men to experience a permanent job separation

While the differences in overall job separations between women and men were minor among workers who had a job separation between 2005 and 2015, women were less likely than men to experience a permanent job separation (i.e., a separation where employees do not return to their employer during the year of the separation or in the following year) (Chart 2). Most of the existing literature does not differentiate between permanent and temporary job separations, but instead considers moves to different jobs or moves from employment to unemployment. Therefore, a direct comparison with other studies is difficult.

Generally speaking, existing literature based on the European labour market indicates that women are less likely to make job-to-job moves (Hirsch and Schnabel 2012; Eryar and Tekgüç 2014), which is consistent with the trend observed here. More specifically, women were more likely than men to stay with the same employer, even after accounting for the number of workers who moved from employment to unemployment. There may be many reasons behind this phenomenon—including gender-based factors such as family responsibilities, including housework and childcare (Fuller 2008; Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz 2010)—or other job-specific characteristics, such as unionization (Hirsch and Schnabel 2012).

Data table for Chart 2

| Female workers | Male workers | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 2005 | 40.1 | 45.4 |

| 2006 | 40.0 | 44.1 |

| 2007 | 38.7 | 44.5 |

| 2008 | 37.2 | 42.5 |

| 2009 | 33.6 | 37.8 |

| 2010 | 33.8 | 40.2 |

| 2011 | 33.4 | 40.0 |

| 2012 | 32.7 | 39.7 |

| 2013 | 32.2 | 38.2 |

| 2014 | 34.3 | 39.7 |

| 2015 | 32.5 | 38.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. | ||

Unlike men, women with no permanent job separation between 2005 and 2015 had higher wage growth than women with a permanent job separation

Previous studies based on the European labour market have found that women faced a higher penalty than men for taking time out of the labour market (Manning and Swaffield 2008). The results of this study support this finding (Table 1). Among women (comparison by column), on average, the log weekly wage growth was 0.84 percentage points higher for those who had no permanent job separation compared with those who moved jobs. The opposite was found for men, with a difference of 0.47 percentage points.

However, when the results are compared by gender (comparison by row), among those who had no permanent job separation, women’s log weekly wage growth was 0.70 percentage points higher than that of men. The opposite was found for workers who had permanent job separations. In addition, for those who had a permanent job separation, women’s log weekly wage growth was 0.61 percentage points lower than that of men.

These results suggest that women were penalized for permanent job separations, while men were rewarded. One possible explanation is that women are less inclined than men to make “wages increasing” voluntary job-to-job moves (e.g., job hopping) (Hirsch and Schnabel 2012).

| Status of permanent job separation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No job separation | At least one job separation | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| percent | ||||

| Weekly wage growth, female workers (log) | Note ...: not applicable | 5.95Note *** Table 1 Note §§ | Note ...: not applicable | 5.11Table 1 Note §§ |

| Weekly wage growth, male workers (log) | 5.25Note * | Note ...: not applicable | 5.72 | Note ...: not applicable |

... not applicable

† significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.10) § significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.05) §§§ significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.001) ‡ significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by column (reference group: individuals with at least one job separation). Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||||

Quitting and layoffs were the leading reasons for permanent job separations for both women and men

In addition to the type of job separation, the reason for a job separation is also an important factor that could affect the gender wage gap (Manning and Swaffield 2008). In Canada, between 2005 and 2015, among individuals who had a permanent job separation, the leading reasons for the job separations for both women and men were quitting or being laid off (Table 2). However, women were less likely than men to experience permanent job separations because of layoffs and quitting. Conversely, women were more likely than men to experience permanent job separations because of parental or maternity leave.

| Reason for permanent job separation | Share of total number of permanent job separations | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| percent | ||

| Layoff | 7.75Note *** | 12.92 |

| QuitTable 2 Note 1 | 15.60Note *** | 17.93 |

| Parental or maternity leave | 2.84Note *** | 0.19 |

| OtherTable 2 Note 2 | 7.48Note *** | 8.90 |

** significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.01) † significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||

Among reasons for permanent job separations, women’s wage growth is lower than men’s

Previous studies based on the 1986 to 1987 Labour Market Activity Survey found that, overall, both women and men who changed jobs in 1986 realized short-term wage gains. However, women who were laid off or quit for personal reasons had substantially greater wage losses than men (Abbott and Beach 1994). The results of the present study support this finding, with more recent data (Table 3).

Among reasons for permanent job separations reported in workers’ records of employment, women’s log weekly wage growth was lower than that of men. For instance, for “layoff” and “quit,” women’s log weekly wage growth was lower than that of men by 0.49 percentage points and 0.80 percentage points, respectively. Similarly, the log weekly wage growth of women who had a permanent job separation because of parental or maternity leave was 0.42 percentage points lower than that of men. As seen in Table 2, although women were less likely than men to experience a permanent job separation for the reasons “layoff” and “quit,” their log weekly wage growth was still lower compared with that of their male counterparts. This means that female workers in Canada faced higher penalties for taking time out of the labour market compared with their male counterparts, regardless of the reason for the job separation.

| Weekly wage growth (log) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| percent | ||

| Reason for permanent job separation | ||

| Layoff | 5.15Note * | 5.64 |

| Quit | 5.08Note ** | 5.88 |

| Parental or maternity leave | 3.74Note ** | 4.16 |

| Other | 4.85Note * | 5.35 |

| Overall wage growth | 5.11Note ** | 5.72 |

† significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||

Temporary job separations

Women were more likely than men to experience a temporary job separation

In contrast to permanent job separation, among individuals who had a job separation between 2005 and 2015, women were more likely than men to experience a temporary job separation (i.e., a separation where employees return to their employer during the year of the separation or in the following year) (Chart 3). More specifically, compared with men, women were more likely to leave their employer temporarily, but to return within a year. Again, since most of the existing literature does not differentiate between permanent and temporary job separations, a direct comparison with other studies is difficult. A comparison is especially difficult in this case since the definition of temporary job separation derived from the LWF is unique: it captures the employer-level mobility change (return to previous employer or not) instead of voluntary job-to-job moves that could potentially be beneficial to wage growth (Hirsch and Schnabel 2012).

Data table for Chart 3

| Female workers | Male workers | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 2005 | 62.3 | 58.3 |

| 2006 | 62.7 | 59.5 |

| 2007 | 64.0 | 59.4 |

| 2008 | 65.4 | 61.6 |

| 2009 | 69.0 | 66.2 |

| 2010 | 68.5 | 63.9 |

| 2011 | 68.7 | 63.3 |

| 2012 | 69.4 | 63.9 |

| 2013 | 70.1 | 65.1 |

| 2014 | 68.1 | 63.8 |

| 2015 | 70.0 | 64.8 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. | ||

Women who had no temporary job separation between 2005 and 2015 had a lower wage growth than those who did, while the differences among men were not as large

Unlike the results on permanent job separation and wage growth, women who had no temporary job separation between 2005 and 2015 had a lower wage growth than those who did (Table 4). More specifically, among women (comparison by column), on average, the log weekly wage growth was 0.74 percentage points lower for those who had no temporary job separation compared with those who had a separation. The same was found for men, with a smaller difference (0.10 percentage points), although the differences are not statistically significant. When results are compared across genders (comparison by row), among workers who had no temporary job separation, women’s log weekly wage growth was 0.76 percentage points lower than that of men, while the same was found for individuals who had a temporary job separation. Among workers who had a temporary job separation, women’s log weekly wage growth was 0.12 percentage points lower than that of men. However, unlike with permanent job separation, the differences in wage growth by gender are not statistically significant, which suggests that temporary job separation has little to no impact on observed differences in wage growth by gender. In summary, both women and men were slightly better off as a result of temporary job separation, although women benefited slightly less than men.

| Status of temporary job separation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No job separation | At least one job separation | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| percent | ||||

| Weekly wage growth, female workers (log) | Note ...: not applicable | 4.74Table 4 Note † | Note ...: not applicable | 5.48 |

| Weekly wage growth, male workers (log) | 5.50 | Note ...: not applicable | 5.60 | Note ...: not applicable |

... not applicable

** significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.01) *** significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.001) § significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.05) §§ significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.01) §§§ significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.001) ‡ significantly different from reference category by row (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by column (reference group: individuals with at least one job separation). Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||||

Layoffs and parental or maternity leave were the leading reasons for temporary job separations for women, while layoffs and other reasons were the leading reasons for men

Layoffs and parental or maternity leave were the leading reasons for temporary job separations for women (Table 5). For men, layoffs and other reasons were the leading reasons. Compared with permanent job separations, findings for temporary job separations are quite different. In particular, parental or maternity leave, not quitting, was one of the top reasons for the separation for women. Also, for men, “other reasons” were listed as one of the top reasons for job separation, instead of quitting. When results are compared across genders, women were less likely than men to experience a temporary job separation because of layoffs and other reasons. However, women were much more likely than men to experience a temporary job separation because of parental or maternity leave.

| Reason for temporary job separation | Share of total number of temporary job separation | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| percent | ||

| Layoff | 23.17Note *** | 32.30 |

| Quit | 4.52 | 4.35 |

| Parental or maternity leave | 22.15Note *** | 2.42 |

| Other | 11.45Note *** | 21.33 |

** significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.01) † significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||

For those who experienced a temporary job separation because of layoffs and quitting, women’s wage growth was lower than that of men

Unlike with permanent job separation, women’s log weekly wage growth was lower than that of men only for separations because of layoffs and quitting (Table 6). Women’s log weekly wage growth was higher than that of men for separations because of parental or maternity leave and other reasons. For instance, women’s log weekly wage growth was 0.75 percentage points and 0.02 percentage points higher than that of men for parental or maternity leave and other reasons, respectively. Compared with permanent job separation, temporary job separations because of parental or maternity leave and other reasons had small positive effects on women’s log weekly wage growth compared with that of men.

As seen in Table 5, although women were more likely than men to have a temporary job separation because of parental or maternity leave and other reasons, they were not penalized for taking time out of the labour market. This is the opposite of what was observed for permanent job separations. However, when the job separation was because of layoffs and quitting, women still had a lower level of wage growth than men, which is similar to what was observed for permanent job separations.

| Weekly wage growth (log) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| percent | ||

| Reason for temporary job separation | ||

| Layoff | 5.25Note * | 5.46 |

| Quit | 5.13Note * | 5.53 |

| Parental or maternity leave | 5.51Note * | 4.76 |

| Other | 5.78Note * | 5.76 |

| Overall wage growth | 5.48Note * | 5.60 |

*** significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.001) † significantly different from reference category by column (p < 0.10) Note: Data presented in percentage by row (reference group: male). Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Worker File linked to 2006 and 2016 Census long-form data. |

||

Conclusion

Previous studies based on the European labour market highlight the importance of examining the differences in early career job mobility, including the type of job separation and reason for the separation. Information on gender-based differences in early career job mobility for young workers in Canada remains mostly unclear because of the lack of relevant studies. To fill this gap, this article discusses the main differences by gender in early career job mobility for young workers in Canada, and the potential impact of these differences on wage growth over the first 10 years of a worker’s career, based on the LWF–census linked data file.

The results of this study showed that women were less likely than men to experience a permanent job separation, and more likely than men to have a temporary job separation during the first 10 years of their career. This is consistent with findings from existing literature based on the European and American labour markets. However, women were penalized for permanent job separations, while men were rewarded. For instance, for those who had no permanent job separation, women’s weekly wage growth was higher than that of men. However, among those who had a permanent job separation, women had lower weekly wage growth compared with men. Both women and men were slightly better off as a result of temporary job separations, although women benefited slightly less than men.

Lastly, the leading reasons for permanent job separations for both women and men were layoffs and quitting. The leading reasons for temporary job separations were layoffs and parental or maternity leave for women, and layoffs and other reasons for men. Compared with men, women were less likely to experience a temporary job separation because of layoffs and other reasons. However, women were much more likely than men to experience a temporary job separation because of parental or maternity leave. Overall, women’s weekly wage growth was lower than that of men for the majority of the job separation reasons investigated, except for temporary job separations because of parental or maternity leave and other reasons. These results suggest that a gender-based gap in wage growth exists because of differences in early job mobility. This could be a channel that ultimately contributes to the unexplained gender-based wage disparity observed in Canada.

References

Abbott, M. G., and C. M. Beach. 1994. “Wage changes and job changes of Canadian women: Evidence from the 1986-87 Labour Market Activity Survey.” The Journal of Human Resources 29 (2): 429–460.

Bertrand, M., C. Goldin, and L. F. Katz. 2010. “Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2 (3): 228–255.

UN Women. 2017. Progress of the world’s women 2015–2016. New York: United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women.

Eryar, D. and H. Tekgüç. 2014. “Gender effect in explaining mobility patterns in the labor market: A case study of Turkey.” The Developing Economies 52 (4): 322–350.

Fuller, S. 2008. “Job mobility and wage trajectories for men and women in the United States.” American Sociological Review 73 (1): 158–183.

Haltiwanger, J., H. Hyatt, and E. McEntarfer. 2018. “Who moves up the job ladder?” Journal of Labor Economics 36 (1): 301–336.

Hirsch, B., and C. Schnabel. 2012. “Women move differently: Job separations and gender.” Journal of Labor Research 33 (4): 417–442.

Manning, A., and J. Swaffield. 2008. “The gender gap in early‐career wage growth.” The Economic Journal 118 (530): 983–1024

Orser, B., C. Elliott, and W. Cukier. 2019. Strengthening Ecosystem Supports for Women Entrepreneurs: Ontario Inclusive Innovation (i2) Action Strategy. Diversity Institute, Ryerson University.

Pelletier, R., M. Patterson, and M. Moyser. 2019. The gender wage gap in Canada: 1998 to 2018. Labour Statistics: Research Papers. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75-004-M2019004. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Date modified: