Canadian youth and full-time work: A slower transition

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Families across the country often discuss the job prospects of young people and how these prospects have changed since the days of their parents and grandparents. These conversations can be full of anecdotes and questions about generations past. How have the employment opportunities of young women changed since Canada's Centennial in 1967? Can a young man still follow in his father's footsteps and get a full-time job out of school? Can young people expect to make more than their parents did when they were young?

This month's edition of Canadian Megatrends takes a more empirical approach to some of these questions, looking at labour force participation, unemployment, full-time and part-time work, and real wages for workers in Canada from 1946 to 2015.

The transitions to the labour force have slowed as young people spend more time in school or training, and then enter a workforce that has changed significantly over seven decades.

Youth participation in the labour force has changed remarkably over time

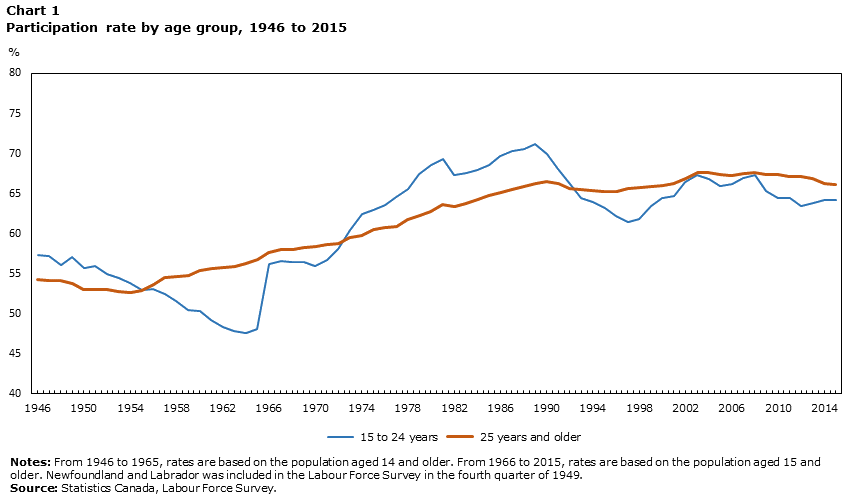

Since the 1940s, Canadian youth aged 24 and younger have participated in the working world at a very different rate than older adults. From 1946 to 2015, the youth labour force participation rate (those who are employed or seeking employment) has varied from a low of 47.6% in 1964 to a high of 71.2% in 1989.

Description for Chart 1

| Year | 15 to 24 years | 25 years and older |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 1946 | 57.3 | 54.2 |

| 1947 | 57.2 | 54.1 |

| 1948 | 56.1 | 54.1 |

| 1949 | 57.1 | 53.7 |

| 1950 | 55.7 | 53.0 |

| 1951 | 55.9 | 53.0 |

| 1952 | 54.9 | 53.0 |

| 1953 | 54.5 | 52.7 |

| 1954 | 53.8 | 52.6 |

| 1955 | 53.0 | 52.9 |

| 1956 | 53.1 | 53.6 |

| 1957 | 52.5 | 54.5 |

| 1958 | 51.6 | 54.6 |

| 1959 | 50.4 | 54.8 |

| 1960 | 50.3 | 55.4 |

| 1961 | 49.2 | 55.6 |

| 1962 | 48.3 | 55.7 |

| 1963 | 47.8 | 55.9 |

| 1964 | 47.6 | 56.3 |

| 1965 | 48.1 | 56.7 |

| 1966 | 56.2 | 57.6 |

| 1967 | 56.6 | 58.0 |

| 1968 | 56.5 | 58.0 |

| 1969 | 56.4 | 58.3 |

| 1970 | 56.0 | 58.4 |

| 1971 | 56.7 | 58.6 |

| 1972 | 58.1 | 58.8 |

| 1973 | 60.5 | 59.5 |

| 1974 | 62.5 | 59.8 |

| 1975 | 62.9 | 60.5 |

| 1976 | 63.6 | 60.8 |

| 1977 | 64.6 | 60.9 |

| 1978 | 65.6 | 61.7 |

| 1979 | 67.4 | 62.3 |

| 1980 | 68.6 | 62.8 |

| 1981 | 69.3 | 63.6 |

| 1982 | 67.3 | 63.4 |

| 1983 | 67.6 | 63.8 |

| 1984 | 68.0 | 64.2 |

| 1985 | 68.6 | 64.8 |

| 1986 | 69.7 | 65.1 |

| 1987 | 70.3 | 65.5 |

| 1988 | 70.6 | 65.9 |

| 1989 | 71.2 | 66.3 |

| 1990 | 69.9 | 66.5 |

| 1991 | 68.1 | 66.2 |

| 1992 | 66.2 | 65.6 |

| 1993 | 64.4 | 65.5 |

| 1994 | 63.9 | 65.4 |

| 1995 | 63.2 | 65.2 |

| 1996 | 62.2 | 65.2 |

| 1997 | 61.5 | 65.6 |

| 1998 | 61.8 | 65.8 |

| 1999 | 63.5 | 65.9 |

| 2000 | 64.4 | 66.0 |

| 2001 | 64.7 | 66.2 |

| 2002 | 66.5 | 66.9 |

| 2003 | 67.3 | 67.6 |

| 2004 | 66.8 | 67.6 |

| 2005 | 65.9 | 67.4 |

| 2006 | 66.2 | 67.2 |

| 2007 | 67.0 | 67.5 |

| 2008 | 67.3 | 67.6 |

| 2009 | 65.3 | 67.4 |

| 2010 | 64.5 | 67.4 |

| 2011 | 64.5 | 67.1 |

| 2012 | 63.5 | 67.1 |

| 2013 | 63.8 | 66.9 |

| 2014 | 64.2 | 66.3 |

| 2015 | 64.2 | 66.1 |

| Notes: From 1946 to 1965, rates are based on the population aged 14 and older. From 1966 to 2015, rates are based on the population aged 15 and older. Newfoundland and Labrador was included in the Labour Force Survey in the fourth quarter of 1949. Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||

While adults aged 25 and older joined the labour force at a fairly steady rate from 1946 to 2015, the participation rate of young people was much less stable during this time. Following the Second World War, the proportion of youth aged 14 to 24 who were either working or seeking employment declined steadily for almost two decades, from 57.3% in 1946 to 47.6% in 1964. This decrease coincided with all provinces raising their school-leaving ages.

In 1965, Canada stopped including 14-year-olds in the Labour Force Survey. Following this change, the labour force participation rate for youth rose sharply, jumping from 48.1% in 1965 to 56.5% in 1966.

After plateauing during the rest of the 1960s, youth participation increased again in the 1970s, so that in 1981, almost 7 in 10 Canadians aged 15 to 24 (69.3%) were either employed or looking for work. Youth labour force participation reached its highest point in 1989, peaking at 71.2%.

The increase observed from the mid-1960s to the late 1980s was driven mainly by the growing entry of young women in the labour market, which in turn was fostered by the growing importance of service sector jobs and changes in women's attitudes towards family and work.

Following the 1990–1992 recession and the ensuing slack labour market that persisted until the late 1990s, participation declined, falling back to the same levels observed in the mid-1970s. The turn of the millennium saw young people initially returning to the labour force, then stepping back slightly after the recession of 2008–2009. However, youth participation in the labour force was fairly steady through the 2000s and 2010s, staying close to the levels of the early 1990s and mid-1970s.

Youth unemployment always higher

However, participation rates are only one part of young people's experience of the labour market. A second major factor is whether youth are able to find employment once they enter the workforce.

The youth unemployment rate varied widely from 1946 to 2015. Relatively low until the mid-1950s, it climbed 5.9 percentage points from 1956 to 1958, peaking at 11.1%. While youth unemployment briefly dropped below 6% again in 1966 (5.6%), it was back up to 11.1% in 1971.

The unemployment rate for workers aged 15 to 24 rose further during the 1970s as the relatively large cohorts of baby boomers entered the labour market. Following the 1981–1982 recession, youth unemployment reached its highest point in 1983, when 19.2% of young workers were unemployed. The recovery of the Canadian economy from 1984 to 1989 led to a steady decline in youth unemployment through the rest of the 1980s. Youth unemployment rose in the early 1990s after the 1990–1992 recession, and again following the 2008–2009 recession. From 1990 to 2015, it remained between 17.2% (1992 and 1993) and 11.2% (2007).

The levels following the 2008–2009 recession were similar to those observed in the mid-1970s.

Description for Chart 2

| Year | 15 to 24 years | 25 years and older |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 1946 | 4.9 | 2.8 |

| 1947 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| 1948 | 3.8 | 1.8 |

| 1949 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| 1950 | 5.6 | 3.0 |

| 1951 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| 1952 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| 1953 | 4.6 | 2.5 |

| 1954 | 6.9 | 3.9 |

| 1955 | 6.7 | 3.7 |

| 1956 | 5.2 | 2.9 |

| 1957 | 7.3 | 3.9 |

| 1958 | 11.1 | 5.9 |

| 1959 | 9.4 | 5.0 |

| 1960 | 11.0 | 5.8 |

| 1961 | 10.9 | 6.1 |

| 1962 | 9.4 | 4.9 |

| 1963 | 9.3 | 4.4 |

| 1964 | 8.0 | 3.7 |

| 1965 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| 1966 | 5.6 | 2.6 |

| 1967 | 6.5 | 2.9 |

| 1968 | 7.7 | 3.4 |

| 1969 | 7.5 | 3.4 |

| 1970 | 10.0 | 4.2 |

| 1971 | 11.1 | 4.5 |

| 1972 | 10.9 | 4.6 |

| 1973 | 9.6 | 4.1 |

| 1974 | 9.3 | 3.9 |

| 1975 | 12.0 | 5.0 |

| 1976 | 12.4 | 5.1 |

| 1977 | 13.8 | 5.8 |

| 1978 | 14.0 | 6.2 |

| 1979 | 12.7 | 5.6 |

| 1980 | 12.8 | 5.5 |

| 1981 | 12.8 | 5.7 |

| 1982 | 18.2 | 8.6 |

| 1983 | 19.2 | 9.6 |

| 1984 | 17.4 | 9.4 |

| 1985 | 15.8 | 8.9 |

| 1986 | 14.7 | 8.1 |

| 1987 | 13.2 | 7.6 |

| 1988 | 11.5 | 6.8 |

| 1989 | 10.9 | 6.7 |

| 1990 | 12.3 | 7.1 |

| 1991 | 15.8 | 9.1 |

| 1992 | 17.2 | 9.9 |

| 1993 | 17.2 | 10.2 |

| 1994 | 15.9 | 9.3 |

| 1995 | 14.8 | 8.4 |

| 1996 | 15.4 | 8.5 |

| 1997 | 16.3 | 7.7 |

| 1998 | 15.1 | 7.0 |

| 1999 | 14.1 | 6.3 |

| 2000 | 12.7 | 5.7 |

| 2001 | 12.9 | 6.1 |

| 2002 | 13.6 | 6.5 |

| 2003 | 13.6 | 6.4 |

| 2004 | 13.4 | 5.9 |

| 2005 | 12.4 | 5.7 |

| 2006 | 11.7 | 5.3 |

| 2007 | 11.2 | 5.0 |

| 2008 | 11.6 | 5.1 |

| 2009 | 15.4 | 7.0 |

| 2010 | 14.9 | 6.8 |

| 2011 | 14.3 | 6.3 |

| 2012 | 14.4 | 6.0 |

| 2013 | 13.7 | 5.9 |

| 2014 | 13.5 | 5.8 |

| 2015 | 13.2 | 5.8 |

| Notes: From 1946 to 1965, rates are based on the population aged 14 and older. From 1966 to 2015, rates are based on the population aged 15 and older. Newfoundland and Labrador was included in the Labour Force Survey in the fourth quarter of 1949. Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||

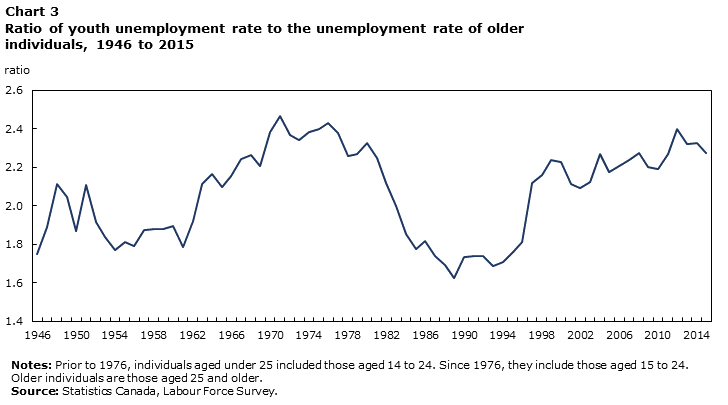

Regardless of the period considered, the youth unemployment rate has always been higher than the unemployment rate of older workers. The difference reflects a variety of factors. Whenever firms implement layoffs based on seniority rules, young workers are more likely to lose their job than their older counterparts. In addition, young workers are overrepresented in small firms, which tend to have higher-than-average layoff rates. Finally, at the beginning of their career, young workers change jobs more often than older workers, looking for a position whose requirements fit their skills. Such job searches sometimes entail some unemployment.

The result is that from 1946 to 2015, the youth unemployment rate followed similar patterns to the unemployment rate of older workers, but was always at least 1.6 times higher. The greatest disparities between the unemployment rates of youth and older workers occurred in the mid-1970s—when young people were just over 2.5 times as likely to be unemployed as older adults—and in 2012, when youth unemployment was 2.4 times higher than the rate for older workers.

Description for Chart 3

| Year | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 1.75 | |

| 1947 | 1.89 | |

| 1948 | 2.11 | |

| 1949 | 2.05 | |

| 1950 | 1.87 | |

| 1951 | 2.11 | |

| 1952 | 1.92 | |

| 1953 | 1.84 | |

| 1954 | 1.77 | |

| 1955 | 1.81 | |

| 1956 | 1.79 | |

| 1957 | 1.87 | |

| 1958 | 1.88 | |

| 1959 | 1.88 | |

| 1960 | 1.90 | |

| 1961 | 1.79 | |

| 1962 | 1.92 | |

| 1963 | 2.11 | |

| 1964 | 2.16 | |

| 1965 | 2.10 | |

| 1966 | 2.15 | |

| 1967 | 2.24 | |

| 1968 | 2.26 | |

| 1969 | 2.21 | |

| 1970 | 2.38 | |

| 1971 | 2.47 | |

| 1972 | 2.37 | |

| 1973 | 2.34 | |

| 1974 | 2.38 | |

| 1975 | 2.40 | |

| 1976 | 2.43 | |

| 1977 | 2.38 | |

| 1978 | 2.26 | |

| 1979 | 2.27 | |

| 1980 | 2.33 | |

| 1981 | 2.25 | |

| 1982 | 2.12 | |

| 1983 | 2.00 | |

| 1984 | 1.85 | |

| 1985 | 1.78 | |

| 1986 | 1.81 | |

| 1987 | 1.74 | |

| 1988 | 1.69 | |

| 1989 | 1.63 | |

| 1990 | 1.73 | |

| 1991 | 1.74 | |

| 1992 | 1.74 | |

| 1993 | 1.69 | |

| 1994 | 1.71 | |

| 1995 | 1.76 | |

| 1996 | 1.81 | |

| 1997 | 2.12 | |

| 1998 | 2.16 | |

| 1999 | 2.24 | |

| 2000 | 2.23 | |

| 2001 | 2.11 | |

| 2002 | 2.09 | |

| 2003 | 2.13 | |

| 2004 | 2.27 | |

| 2005 | 2.18 | |

| 2006 | 2.21 | |

| 2007 | 2.24 | |

| 2008 | 2.27 | |

| 2009 | 2.20 | |

| 2010 | 2.19 | |

| 2011 | 2.27 | |

| 2012 | 2.40 | |

| 2013 | 2.32 | |

| 2014 | 2.33 | |

| 2015 | 2.28 | |

| Notes: Prior to 1976, individuals aged under 25 included those aged 14 to 24. Since 1976, they include those aged 15 to 24. Older individuals are those aged 25 and older. Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||

Young people increasingly likely to hold part-time jobs

In the mid-1970s, it was more common for young individuals who were not full-time students to be employed full time (i.e. in jobs that involve at least 30 hours per week).

From 1976 to 1978, the full-time employment rate—the percentage of the population with a full-time job—averaged 76% for men aged 17 to 24 and 58% for women in the same age group who were not in school full time. By the mid-2010s, i.e. from the beginning of 2014 to the third quarter of 2016, the corresponding percentages were 59% for men and 49% for women.

The drop in full-time employment rates among non-full-time students was already apparent in the late 1990s and thus originated long before the 2008–2009 recession.

Individuals aged 17 to 24, both with and without a university degree, experienced a substantial decline in full-time employment from the late 1970s to the mid-2010s.

The decline in full-time employment rates among youth was driven mainly by gains in part-time employment rather than by decreases in labour force participation or higher unemployment. In other words, young people were more likely to work in part-time positions, often involuntarily, rather than be unemployed or leave the labour force.

Wages decreasing for youth with full-time jobs

Among those young workers with full-time jobs, wages varied substantially from the 1980s to the 2010s. The median hourly wage (in constant dollars) earned by youth aged 17 to 24 with full-time jobs declined steadily from 1981 to 1998, following similar patterns for both young men and young women. At the lowest point, in 1998, young men with full-time jobs earned 22.2% less than their predecessors in 1981, while young women were paid 18.8% less than young women in 1981.

Wages for this cohort improved unevenly over the 2000s and early 2010s, increasing around 2004 as world oil prices increased, the housing boom intensified and general economic activity gained momentum. However, this increase did not offset the losses in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2015, full-time wages for male workers aged 17 to 24 were 11.2% lower than in 1981, while wages for their female counterparts were 3.0% lower.

Slightly older workers—those aged 25 to 34—had a different experience over this time, especially women. While full-time wages for women aged 25 to 34 stagnated from 1981 to the mid-1990s, they began to climb steadily in 1997, reflecting strong growth in educational attainment and the move to better-paying occupations.

Meanwhile, full-time wages for men aged 25 to 34 dropped through the 1980s and first half of the 1990s, then were stagnant until 2005. It was not until 2013 that men in this age group earned the same real wages as men of the same age in 1981. In 2015, this group's wages were 2.1% higher than they had been in 1981.

Oil-producing provinces remained an exception

There is a notable exception to the trend. From the late 1990s to the mid-2010s, median wages grew much more in the three oil-producing provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, and Alberta than they did in Ontario. Spillover effects of the oil boom accounted for a substantial portion of these interprovincial differences in wage growth. Up until the middle of 2015, full-time employment rates also evolved much more favourably in these three provinces than they did elsewhere in Canada.

References

Galarneau, D., R. Morissette and J. Usalcas. 2013. “What has changed for young people in Canada?” Insights on Canadian Society. Statistics Canada, catalogue no. 75-006-X.

Morissette, R., W. Chan and Y. Lu. 2014. “Wages, youth employment and school enrollment: Recent Evidence from Increases in World Oil Prices.” Analytical Studies Research Paper Series, Statistics Canada, catalogue no. 11F0019M.

Statistics Canada. 2015. “Career Decision-making Patterns of Canadian Youth and Associated Postsecondary Educational Outcomes.” Education Indicators in Canada: Fact Sheet. Statistics Canada, catalogue no. 81-599-X.

Statistics Canada. 2016. “Perspectives on the Youth Labour Market in Canada, 1976 to 2015.” Presentation Series from Statistics Canada About the Economy, Environment and Society, Statistics Canada, catalogue no. 11-631-X.

Contact Information

To enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact René Morissette (rene.morissette@canada.ca; 613-951-3608), Social Analysis and Modelling Division.

- Date modified: