Chapter 2: Tumultuous times: 1972 to 1980

Table of Contents

- The role of Canada's national statistical agency

- A new Chief Statistician is appointed

- Dr. Sylvia Ostry

- The task at hand

- Who's who in Ottawa

- A fundamental look at ourselves

- Centralization

- Human resources

- Relationship with other departments

- A task force is born

- Planning and priority-setting

- Cost-recovery and marketing

- Coordination of statistical activity

- Structural re-organization

- To remain, or not remain, centralized

- Organizational changes

- Bilingualism continues to grow

- Statistics Canada gets two new buildings

- A legal officer is assigned

- An era of greater federal-provincial co-operation

- The Computer Centre operates around the clock

- Notable milestones in the statistical program

- Key releases on government finance and the system of national accounts

- Trade statistics

- Seasonal adjustment and time series analysis

- The agency makes its mark in seasonal adjustment

- A new emphasis on social statistics

- Human Activity and the Environment is born

- International Women's Year

- A general system of editing and imputation

- The Census program

- Wage and price controls

- A new Chief Statistician is appointed

- Dr. Peter Kirkham

- The applecart overturns

- Organizational changes

- Metrification

- Canada's conversion to the metric system

- Re-organization and decentralization

- Proposed relocation of the Ottawa Regional Office

- The protection of personal information

- Notable milestones in the statistical program

- Professionalism at work

- The 1976 Census program

- The international scene

- Fiscal restraint across the government

- The Canada Health Survey

- A negative atmosphere

- A full and constructive review

- Dr. Kirkham departs

- The end of an era

The role of Canada's national statistical agency

With a new Statistics Act just passed in 1971, the role of the agency was very much a topic of discussion within the government. A 1968 task force on government information had found that users were very critical of the timeliness, usefulness, clarity and accessibility of the data produced by Statistics Canada, and federal government departments were increasingly vocalizing their discontent with the agency's responsiveness to their growing and complex needs, particularly those related to policy analysis and program performance evaluation. In April 1972, the agency's executive committee appointed a departmental study group to examine its image and recommend measures for its improvement. The group comprised senior representatives from the subject-matter branches and was to determine what image the agency should try to project, and how. The report was produced under a tight time constraint, as it needed to also feed into recommendations being prepared by the Chief Statistician on the organization and resources of the Bureau. Questions were arising at the time about what the role of a central statistical agency should be, and how it should best function to ensure that priorities were being met in a time of exponentially increasing information demands.

The consensus of the image study was that the agency should strive to attain a number of general objectives. The agency was to be, and be seen to be, central to the business of government and producing not data but information (including carefully abstracted statistics, a combination of statistics with analysis, interpretation, and illustration) with the best practicable combination of timeliness, accuracy and scope. The relevance of that information needed to be continually demonstrated, and its purpose made consistently visible. The information produced was to be objective, and the agency was to be and be seen as "rigorously a-political." The agency also needed to be communicative with active dissemination of information. Lastly, the study found that the agency needed to strive to be responsive to the needs of its various user communities as well as to anticipate new requirements.

The caveat was that Statistics Canada could not aspire to this image until it corrected the operational imbalance between (1) the collection, compilation and physical production of data, and (2) the marketing of its information to users and the communication of information about the agency. The recommendation was therefore that it strengthen its marketing and communications activities and create a new Statistical Information Service to provide better service to users. The report also recommended the development of a basic media relations course for Statistics Canada personnel, and the creation of a parliamentary affairs position.

A new Chief Statistician is appointed

In June 1972, Walter Duffett retired, and Dr. Sylvia Ostry was appointed Chief Statistician of Canada. She was not an unknown to the agency, having been brought in as director of Special Manpower Studies by Simon Goldberg, a position she held from 1964 to 1969. She was known to be extremely productive and highly energetic. This was not an easy switch for the agency, having been for 15 years under the wing of Walter Duffett, someone who had been particularly strong at maintaining a calm and stable environment. Dr. Ostry was brought in, in a sense, to shake up the agency. There is some thought that the government had not been particularly at ease with the agency at the end of Duffett's tenure. This wish to rejuvenate was not unique to Statistics Canada. In fact, the increasing interdepartmental mobility of deputy ministers at the time was meant to discourage insularism and encourage new leadership ideas.

This was also perhaps why Simon Goldberg was not appointed to be the next Chief Statistician, although some insist to this day that he was the prime candidate at the time. He was eloquent, brilliant, and very much a driving force behind automation at the agency. However, he was known to have been a loyal Assistant Chief Statistician to Walter Duffett, something that may not have been an asset to a government seeking to fundamentally change the ways of the agency. While Simon Goldberg was known to be very independent and a harbinger of new ideas, he perhaps was not new enough. Walter Duffett's retirement was an opportunity to introduce fresh ideas and a blank slate by bringing in experts from outside the agency. On the flip side, history would show that such a change could also result in discordance with the culture of a large organization created incrementally over many years. Jacob Ryten, in his introduction to a compendium highlighting important articles over the history of the agency, would aptly summarize that "there is a permanent tension within statistical organizations between the will to innovate and the sense that continuity must be preserved."

Such tensions were played out across the senior management of the agency – between the more conservative faction and the newer faction (including Simon Goldberg and his protégé Ivan Fellegi) who were embracing change and who eagerly welcomed the introduction of computing at the agency.

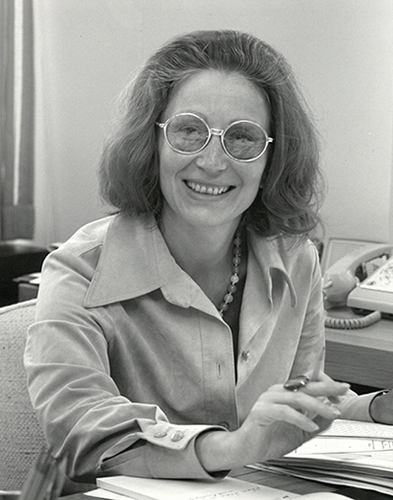

Dr. Sylvia Ostry

Not only was Dr. Sylvia Ostry Canada's first and only female Chief Statistician, she was also Canada's first female deputy minister. In response to media, she always rejected the notion that her appointment had any element of "tokenism"—her resume certainly spoke for itself. She was born in north Winnipeg in 1927 and studied economics at McGill, where she earned a bachelor's degree in economics in 1948 and a Master of Arts in 1950; as well, she earned a doctorate from Cambridge and McGill in 1954. After teaching and doing research at McGill, the Université de Montréal, and the University of Oxford, she joined Statistics Canada, serving as Assistant Director for Research and then Director in the Labour Division, from 1964 to 1969. She held the position of Chair of the Economic Council of Canada for three years, before returning to the agency in 1972 to serve as Chief Statistician.

Her career at Statistics Canada came to an end in 1975, when she was reassigned to the Department of Consumer and Corporate Affairs as Deputy Minister, a post she held until 1978. The other positions held by Dr. Ostry during her career include Head of the Department of Economics and Statistics at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Deputy Minister of International Trade, Ambassador for Multilateral Trade Negotiations, and Canada's sherpa—Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's Personal Representative—at the G7 summits from 1985 to 1988. She has been awarded 19 honorary degrees from universities in Canada and abroad. She received the Order of Canada in 1978 and was promoted to Companion of the Order of Canada in 1990, the highest award in the national system of honours. She was also Chancellor of the University of Waterloo from 1991 to 1996, and was named Chancellor Emerita in 1997.

In 2002, to celebrate Dr. Ostry's 75th birthday, The Sterling Public Servant was produced by former Assistant Chief Statistician Jacob Ryten. This was a festschrift, a collection of papers from eminent contributors on subjects related to her career and reflecting the relevance and importance of her academic and governmental contributions to Canada. It included congratulatory letters from all prime ministers living at the time.

The task at hand

One of Dr. Ostry's first tasks at the agency was to take the reins of the study begun by Walter Duffett, for the purpose of making the agency a more responsive and effective source of information for the country. The study was given additional authority and urgency by a letter from Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau dated June 1, 1972, which congratulated Dr. Ostry on her Governor-in-Council appointment and outlined his perspective on the role of Statistics Canada and the way in which he hoped it would develop. He referred to her uncommon ability to keep in mind the broader perspective of the public service as a whole while at the same time being engaged in specific departmental duties, and expressed his hope that she would encourage this attitude throughout the agency.

The Prime Minister's letter referred to the list of priority problems identified by the government when it took office, in 1968, noting that "information" was at the top of the list. Some early work on the priority had culminated in the creation of Information Canada, which was a new department with the responsibility of improving communication between the government and Canadians. The other priority element was the question of how best to ensure that the government received and collected the relevant information on which to base its operational policy and planning decisions. He asked her, as one of her first duties, to undertake a study of the relationship between the agency and its clients and to make recommendations for assisting the government in determining statistical priorities. She was to consider how the responsibilities and resources for the collection and processing of statistical data should best be allocated between Statistics Canada and other federal agencies. She was also to look into procedures for enabling ministers to express their views on statistical priorities as well as the proper relationship between the Chief Statistician and the policy-making process to improve the agency's anticipation of statistical requirements. Lastly, she was asked to complete a review of the structure, financial arrangements and operating procedures within Statistics Canada, and to seek improvements in the usefulness of statistics, especially those required for program performance evaluation and policy analysis. Just a short list!

A month later, Dr. Ostry met with both the Chair of the Public Service Commission and the Secretary of the Treasury Board, to whom she indicated in later correspondence: "I hope that over the course of the next few months my discussions with your officials will expedite the process of review and assessment of the agency and will culminate in a rational and feasible proposal for structural and organizational changes."

Dr. Ostry would remark in an address to businesses at a conference on statistics for corporate decision-making that "it has become commonplace for statisticians to note the explosion in the demand for information, but the observation is no less true for its frequent repetition. The progressively larger role of government in the areas of economic and social policy may be lamented by some sturdy spirits among you, but it is a fact of life which, for us, manifests itself in unremitting requests for more information on more and more subjects… The needs of business are fast becoming as insistent and demanding as those of government. To navigate in the waters of today's complex national and international business milieu requires increasingly sophisticated guidance systems." The national statistics system was meant to be that guidance system, and it required an overhaul.

Who's who in Ottawa

Few might realize that we had a celebrity in our midst. Dr. Ostry knew everyone who was anyone in Ottawa. A lengthy Saturday Night magazine article about Dr. Ostry by George Bain, written while she was working for the OECD in Paris in 1981, notes that "next only to Pierre and Margaret, no pair had more celebrity in Ottawa in the 1970s than the Ostrys." The article also remarks that "Two things almost everyone – including Sylvia Ostry – says about her are that she is intensely ambitious and that she works like a dog at whatever she is doing."

A fundamental look at ourselves

In her first month as Chief Statistician, Dr. Ostry asked her senior staff to reflect on some of the major issues that would confront the agency in the 1970s, inviting proposals on all facets of the Bureau's operations, including its objectives, strategy, structure, and issues. She called it a "fundamental look at ourselves," and indicated that all proposals would be treated confidentially and should be directed to her personally. There were a great many heartfelt memos authored to that intent, outlining what Statistics Canada in the 1970s would be like, how the agency might step up to meet the needs of the times, including some of the current challenges facing the agency.

Centralization

There were a number of recurrent themes, one of which was growing frustration over the centralization of functions. Centralization was new—recall that the agency was extremely siloed, each division essentially operating largely as a separate entity, and that there was a great deal of frustration with competition for the attention of the service areas—especially when each division was used to having its own dedicated services at its beck and call. One memo spoke of the challenge of obtaining services as akin to "leading a cavalry charge into a swamp." Communication within the Bureau was lacking as well—for example, one director spoke of not knowing for several months that a particular centralized service area had been created. One memo to Dr. Ostry spoke of the apparent contradiction in the agency's organization: how to reconcile the autonomy granted to the Bureau's divisions with its ideological commitment to integration. Some of the disjointedness of the organization and lack of communication undoubtedly arose as a result of physical separation of the different divisions of the agency. Even in 1974, the head office of Statistics Canada was operating from nine different buildings dispersed throughout the city of Ottawa.

Most of the senior staff recognized the challenges brought about by the tremendous growth of the Bureau under Duffett, with a number of memos indicating that the agency could not afford to get much larger. Not only had there been tremendous growth in staff and work, but the complexity of that work was also increasing along with expanding automation. This tied in with another important theme of the memos—the need to more clearly delineate the role and objective of the agency and of its divisions and to do better at setting statistical priorities. There was fuzziness about where responsibilities lay—this was likely exacerbated by the centralization drive. Reference was made to a shortage of senior officers who could focus on strategic issues rather than daily operations.

Human resources

On the human resources side, the memos indicated that staff morale was low and that there were serious problems with recruitment and retention of experienced personnel. Some mentioned the possibility of more opportunity for staff rotation to develop their flexibility and cultivate interest. The narrow specialization of staff was felt to produce excellent statisticians but not necessarily excellent managers, especially in an increasingly interconnected world. By 1974, a job rotation task force would be established to look into the possibility of a job rotation program at the agency. Senior management would find that the program was indeed feasible.

There was no central recruitment of employees at the time. Any manager who needed to hire employees would have to obtain a list of eligible applicants from the Public Service Commission and then interview the applicants of his or her choice. Such a decentralized process would have exacerbated the insularism of the divisions.

Relationship with other departments

There was a general feeling that attitudes in the agency often conveyed a lack of concern for, or disinterest in, other federal departments and the issues they faced. It was felt that the agency was seen merely as a figure factory whose sole goal was to produce data without too much regard to what the statistics measured. There was a need for more data analysis and better marketing to let the world in on the richness of available information. One memo indicated that the Bureau was seen to be conservative, slow-moving, and inflexible, and was considered a junior member of the federal family. Another concluded rather ominously "the future shape of the Bureau must be determined at once. Band-Aids and aspirin will no longer suffice; major surgery and rehabilitation are required. It would be well to initiate corrective measures before terminal bureaucracy brings on a lingering and painful end."

A task force is born

From the deluge of lengthy memos written in response the Dr. Ostry's request, it was obvious that senior managers were in favour of a re-organization and self-renewal. The arguments for significant restructuring were strong, and an equally strong leadership would be needed in order to overcome the inertia within the agency. Although it was agreed that change was needed, bringing it about would not be easy in light of frustration with the many recent attempts in this regard. Assistant Chief Statistician L.E. Rowebottom would aptly assess "our files are graveyards of task force reports, planning papers, and organization charts. Many of our managers have grown cynical and frustrated with the process and with the agonizing task for trying to agree upon and implement change."

Dr. Ostry set up a task force in August 1972 with the goal of evaluating the state of Canada's statistical system and Statistics Canada's role in it. She described it as an intent to clarify and reaffirm the agency's service role towards its clientele, to develop visible and understandable procedures for showing what the agency was reasonably able to do in response to growing demands, and to minimize costs, as the agency's budget had expanded considerably over the previous 15 years. The task force consisted of two senior officers from Statistics Canada, an external consultant, and a representative of the business community with extensive marketing and systems experience. The external consultant had led extensive consultations with federal government users and central agencies, and the group worked essentially full-time, carrying out its review in under six months.

The major findings of the study and subsequent investigations were to improve priority-setting mechanisms in the use of the statistical resources; make the agency's statistical products and services more relevant and accessible and promote their use more vigorously; assume a stronger coordinating role vis-à-vis the statistical activities of other federal departments; and maintain the confidence and support of the public.

Planning and priority-setting

A number of recommendations were advanced by the task force to create more visible and understandable priority-setting mechanisms for the efficient allocation of resources. In a paper presented to the Eighth Conference of Commonwealth Statisticians, author David Worton explains that Statistics Canada had traditionally tried to be "all things to all people" and that this was possible in a relatively stable demand situation, or a situation where its budget was ever-increasing as was the case for most of Duffett's and Ostry's tenures. However, by the early 1970s, it became clear that this was not sustainable—i.e., that something had to give.

A new Policy, Planning, and Evaluation Branch, reporting directly to the Chief Statistician, was created to provide continuous assessment of the statistical system, to ensure that the agency was meeting its mandate, and to help facilitate the integration and balance of the program plans of each of the fields. The evaluation of ongoing program activities would allow the identification of activities which no longer contributed effectively to the attainment of current objectives. The idea was that any net growth would be funded by reallocation of resources within the existing base. In time, this approach would be found to not work well—as it removed necessary decision-making power from senior management.

The report also recommended the development and maintenance of a medium-term plan. There was a great deal of emphasis on the need to forego "incremental planning," or "disjointed incrementalism," referring to the tendency toward a vested interest in what one has been doing for a long time, with meaningful planning happening only at the margins. Medium-term planning was intended to provide a sense of direction for management, assist the orderly and realistic scheduling of interrelated development, and help the agency adjust to urgent policy needs. Such plans were also intended to provide others with a better understanding of the long-term developmental nature of many statistical activities, and help users see how the agency expected to address their particular needs.

Cost-recovery and marketing

The review showed a need to increase timeliness and flexibility in order for the agency to respond to ad hoc information needs and to produce customized tables and analyses for data users. An important outcome was thus the advent of a cost-recovery program to service user-specific needs. A Special Surveys Co-ordination Division was therefore created to carry out new and ad hoc household surveys on a cost-recovery basis. The new division brought together responsibilities for management of household surveys, which had previously been scattered among a number of divisions, and acted as the focal point for special survey work requested by outside agencies. For example, the household income and expenditure area was transferred out of the Prices Division. However, information on the Labour Market was still shared between the Labour Division and the Special Surveys Division, such that conceptual knowledge and management decisions and accountability were divided. The new division was necessary and successful, but in hindsight could have been even more effective.

It was apparent that users were largely unaware of the depth, breadth and potential of the information available to them as Statistics Canada lacked a central focal point for documenting and making known the availability of its data holdings. A Marketing Services Branch was created, headed by an Assistant Chief Statistician, to explain what information was available and how it could be used, and to play a strong role in outreach and consultation. High priority was also given to the extension of User Advisory Services. The number of data access and use specialists was doubled, and regional offices were added as part of the re-organization to make more information available to more people. A pilot project was carried out in Montréal and Toronto regional offices where computer terminals to access the Canadian Socioeconomic Information Management System (CANSIM) were installed. This project was ultimately a success.

The new User Advisory Services focused on developing an effective service for statistical users and maintaining liaison with provincial government bodies. This unit held data usage workshops for municipalities, banks, libraries, and industry. The agency was also conducting seminars across Canada on the work of various subject-matter areas. In 1972/1973, the focus was on labour statistics and agriculture census results. The agency published booklets for business owner-operators, including most notably a series entitled "How to profit from facts," including "How a manufacturer can profit from facts," "How a retailer can profit from facts," and "How contractors and builders can profit from facts." In the interest of greater co-operation and collaboration, the Marketing Services group began to play a strong role in bringing together subject-matter staff with the various industry associations.

In 1974/1975, regional staff visited all of Canada's public libraries with complete collections of the agency's publications. A news bulletin Federal-Provincial Statistical News was also released regularly—it was originally designed to keep the delegates of the federal-provincial conference on economic statistics informed of developments in the agency and in the provinces, but was later broadened in scope. A feedback system designed to improve the flow of information on users and uses of statistics from the regions became operational at the end of 1974. This was also the year in which a program called "Doorstep Diplomacy" was launched to improve interviewers' awareness of the value of good respondent relations. The User Advisory Services Division also acted as the coordinator and secretariat for statistical meetings—in 1976/1977, this included 21 formal federal-provincial meetings.

In 1973/1974, the new marketing services branch produced a booklet providing a summary of the agency and its programs designed for the layperson. A new weekly publication targeted to the layperson, called Infomat, replaced the old Statistics Canada Weekly. Infomat was aimed at audiences who were not necessarily familiar with statistics. By 1974, all publications had become bilingual. While print publications remained the principal medium of dissemination, there was steady growth of other media including CANSIM, microfiches and magnetic tapes.

Coordination of statistical activity

In an address delivered to a conference in 1974, Dr. Ostry refers to the inescapable dilemma of all statistical systems at the time: the burden which the satisfaction of user needs simultaneously placed upon them as respondents. The replacement of direct statistical collection with the exploitation of administrative records was being explored to reduce respondent burden, the most notable progress at the time being the new ability to access income tax returns of corporations and unincorporated businesses.

To this end the report also recommended strengthening the "Rule of 10." Other federal departments would conduct surveys for program evaluation purposes, but there was no suitable mechanism for ascertaining whether the required information already existed elsewhere in the public service, whether the information required justified the response burden, or even whether the instruments used were technically sound. The "Rule of 10" was first implemented in 1966, and had grown out of a recommendation from the Glassco commission, namely, that all departments intending to request statistical information from more than 10 respondents provide the Chief Statistician with copies of the request and all accompanying forms, schedules and questionnaires 10 days before issuing them to respondents. The report recommended greater advance notification of proposed surveys, the review of technical specifications, and suggested means of enforcement.

Administration of the rule would be placed under the responsibility of the new Special Surveys Coordination Division, and a publication was produced to disseminate information about the surveys reported by other departments. The agency produced support material for other departments outlining the procedures that the agency suggested they follow in preparing submissions and describing the aspects of their survey plans that the agency would review. This "Rule of 10" would eventually prove ineffective as it was not adequately followed or enforced.

In hindsight, it is evident that forcing collaboration was not a feasible solution. This regulatory requirement paled in comparison with a robust outreach program in terms of cultivating good relationships and sharing statistical expertise. It has been suggested that, had the agency taken the necessary initiatives to discuss needs with departments, anticipate their requirements, and demonstrate that the agency's input could prove useful to them, they may have welcomed— rather than resented—the participation of Statistics Canada. The surveys taken by other departments could have been used as signals indicating unmet needs, changing requirements, or a communication gap that needed to be addressed.

The review also suggested that Statistics Canada establish satellite operations in other federal departments to enhance responsiveness by facilitating collaboration and joint determination of data needs and to help ensure that administrative files were exploited to the greatest extent possible. In 1975, the Judicial Division established satellite offices within the Ministry of the Solicitor General to service the statistical needs of both departments, as well as those of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Canadian Penitentiary Service and the Canadian Parole Board. In 1977, to facilitate more efficient use of data, a Science Statistics Centre was established as an experimental satellite within the Ministry of State for Science and Technology, and concurrently a new publication program for science statistics was implemented, including a service bulletin and an Annual Review of Science Statistics. The unit would return to the agency in the early 1980s. A successful satellite centre of the Transportation and Communications Division of Statistics Canada had existed since 1966. The Aviation Statistics Centre was located within the Canadian Transport Commission and had a mandate to produce aviation statistics for Transport Canada, the Commission and Statistics Canada. Most data processed by the centre were collected under authority of the Aeronautics Act (as opposed to the Statistics Act) and used principally for regulatory and policy purposes. This would end up being the only lasting statistical satellite. The Aviation Statistics Centre was repatriated to Statistics Canada after deregulation, 31 years later, in 1997.

Structural re-organization

The structure of the organization was essentially revamped in 1973, as it set out to implement the recommendations of Dr. Ostry's task force. This involved the strengthening of top management, the consolidation of activities that should work more closely together, and investment in some underdeveloped functions. One of these underdeveloped functions was economic intelligence for policy analysis. In the early 1970s, some statistical offices were reluctant to provide contextual analysis for fear that objectivity or neutrality could be compromised. Dr. Ostry signalled an increased investment in analytical capabilities and an increased emphasis on policy relevance.

The agency was re-organized into fields—Census, Economic Accounts and Integration, Business Statistics, Household and Institutional Statistics, Statistical Services, and Marketing Services. Branches to support these operations included administration and planning. Under Duffett, many new initiatives had been added as a directorship reporting directly to him, resulting in a great many direct reports. With Ostry's re-organization, the number of areas reporting directly to the Chief Statistician were reduced from 13 to 8, and six Assistant Chief Statistician and two Director General positions were created, each heading a particular subject-matter area or area of functional service. The creation of new Assistant Chief Statistician and Director General positions also instigated the assimilation of new expertise from outside the agency. These eight individuals reported directly to the Chief Statistician and, with her, made up the Executive Committee, the nucleus of the management of the new organization. The intent was to allow directors general to focus on the day-to-day management of the programs, while allowing the assistant chief statisticians to focus on planning and policy questions and overall corporate management. This new organizational structure implied a greater need for project management, inter-disciplinary teams working collaboratively, and cost accounting. While it took a number of years to optimize the structure and function to create successful strategic and operational teams, the basic structure of the agency has remained more or less the same ever since.

As a result of the 1972 reorganization, the management style at the agency was also changing—the mid-1970s marked the beginning of what is now referred to as matrix-management, a style of management to increase flexibility and more efficient use of resources. With specialized separate service areas, interdisciplinary project teams became the norm and project management became crucially important. This was a major cultural shift for many program directors who had grown accustomed to, and who had only ever known, hierarchical authority. Project management skills became valued, as did collaborative teamwork and creative problem-solving. This also required time-reporting and financial systems that supported both program and functional management. All agency-wide financial and resource management information systems were consolidated into one integrated unit. The new integrated management information system, known as "Revision of the Management Process, Practices and Systems" (or REMAPPS), provided cost-behaviour data on the agency's operations to help managers to carry out timely planning and control of programs and projects.

Quote: "The steps we are taking constitute an attempt to isolate pivotal issues and to deal with them in the most dynamic manner possible, given pervasive resource constraints and the exigencies of on-going data production. I am not trying to sell the current state of the Bureau as a statistical utopia. There are still major problems, but I think we are moving in the right direction and I encourage you all to participate in the process of change." (Dr. Ostry, in a speech for Statistics Canada's professional orientation course on April 3, 1973.)

To remain, or not remain, centralized

It was becoming apparent that the agency no longer had a virtual monopoly on statistical data collection, production, maintenance and control. With the proliferation of computerized information management systems in other departments and agencies, more and more statistical activities were taking place in other departments. The study thus assessed Statistics Canada's role as a centralized statistical agency. History had demonstrated that centralization by itself was not sufficient to achieve the objectives of co-ordination. The study noted two options. The first option was for the government to channel most of the additional collection and production activity to Statistics Canada, but at the risk of greater friction with other departments and great difficulty in managing such an extended program. The second option was to accept and encourage the trend toward decentralization but seek to influence it constructively by using the agency's central vantage point to provide a greater degree of coordinating and advisory support. The latter option was embraced: by the late 1970s, the agency was offering a program of publications and instructional seminars, including questionnaire design workshops, information on contracting out survey research, and a directory of individuals, companies and other organizations offering survey research services.

One of the recommendations that came out of the extensive review was to ensure a stronger role for the Treasury Board Secretariat so that it could provide the necessary support to Statistics Canada's coordinating role in the national statistical system. However, before machinery could be devised for assigning responsibilities and for coordinating the national statistical system, it was first necessary to determine what statistics and administrative data were being collected or were planned to be collected by the various branches of the federal government. To this end, an Interdepartmental Task Force on Federal Statistical Activity was authorized by Cabinet in 1973—it was chaired by Ian Midgley, Director General of the General Statistics Branch, and consisted of members from five departments as well as the Bank of Canada, reporting to the Committee of Senior Officials on Government Organization.

The Task Force reported to the Committee that it found existing statistical data sources to be underused and identified a lack of coordination in the statistical activities of government departments. It made a series of recommendations for improvement, including that a "statistical master plan" be developed to outline in broad terms the role and activities appropriate to Statistics Canada and those appropriate to other departments.

The Task Force also proposed the creation of a clearinghouse and data documentation system to enable exchange of information, and the development of guidelines to allow for an increase in accessibility to both survey and administrative data consistent with the principles of confidentiality and privacy. A more co-ordinated dissemination function would indeed be established in 1975 by the creation of a referral centre or "statistical clearinghouse" for users seeking not only data produced by Statistics Canada but also data produced by other contributors to the national statistical system, including other federal departments and agencies, the provinces, institutions and businesses. It turns out that this master plan was not successful, the clearinghouse was relatively short-lived, and eventually the interdepartmental task force quietly faded away.

Organizational changes

Bilingualism continues to grow

When the Official Languages Act was passed in 1969, recognizing French and English as the official languages of all federal institutions in Canada, it did not explicitly grant public servants the right to work in the official language of their choice. In June 1973, a Parliamentary Resolution on Official Languages in the Public Service was passed which confirmed this right, subject to certain conditions. In 1977, Treasury Board adopted a set of official-languages guidelines, which established measures to help implement the official-languages policy, including allowing conditional appointment of unilingual employees to bilingual positions provided they agreed to take language training. It also transferred the responsibility of complying with the Official Languages Program to departments. The agency was therefore involved in developing and implementing a systematic plan for its own official-languages program in 1978/1979, and carrying out training and information sessions on rights and obligations with respect to official languages. The agency offered day and evening courses in both languages, and quickly became a leader in developing bilingual courses and reference material for computer sciences by 1980. It recruited heavily from the CEGEP in Hull, which resulted in the agency having the strongest Francophone participation rate in the Computer Science group of any federal government department.

The agency was experimenting with the honour system for attendance and, in 1973, began to use a new attendance recording system that eliminated the need for most employees to sign a daily attendance sheet. Each employee would instead complete a monthly form and submit it to his or her supervisor for review and tallying.

Statistics Canada gets two new buildings

The R.H. Coats building was being built at the time, and was ready for occupancy in 1975. Some will be amused to learn that the Simon Goldberg Conference room initially had shag carpeting, and that the 26-floor tower was planned to have a total of "25" floors, with the cross-over floor being 14. The architects had designed the first floor to be that above the ground floor, while those installing the elevators and the buttons had other ideas. After numerous delays, staff moved in at a rate of about two floors per week.

The agency was also in the early planning stages for another new building to accommodate the Census and Business Statistics fields. Treasury Board had given its approval for the building in December 1973, and a consulting firm was engaged to conduct an "attitudinal survey" of the new occupants of the R.H. Coats building to assist in the planning for the new building. Construction was completed on the Jean Talon building by 1979, and large portions of the Economic and Social Statistics fields moved in. The building was expressly designed for statistical operations with large data-handling and processing areas, and would house about 2,000 employees. The second floor, as well as most of the first floor and the basement, were specially-secured areas occupied by census operations.

A legal officer is assigned

In 1973, the agency was starting to ensure standard terminology with respect to the legal authority on questionnaires, as some made no reference to legal authority, while others included non-standardized wording. With an agency that had grown so quickly and had very stove-piped areas—there were naturally many differences in how things were carried out from area to area. This was also the year where a part-time legal officer was first assigned to the agency, an assignment that would become full time the following year. Dr. Ostry had requested the assignment of a lawyer as it was felt that the Department of Justice had not been very responsive to Statistics Canada's requests for assistance with recent census refusals. The need for legal advice was growing, especially in connection with the interpretation and application of the newly revised Statistics Act and the resulting new agreements with other federal and provincial departments, especially those under section 10. Other areas requiring legal expertise included internal questions such as confidentiality, the registering of CANSIM as a trademark, and large contracts with outside agencies.

An era of greater federal-provincial cooperation

The revised Statistics Act of 1971 prompted a revision of existing federal-provincial co-operative agreements as well as the development of new agreements. In 1972/1973, staff were loaned to the Prince Edward Island government for a few months to examine the organization and use of information from administrative data files in provincial government departments. Another staff member was loaned to the Saskatchewan government for three months to help define the terms of reference for the province's new Statistical Information Centre.

Plans also began for the newly-minted Federal-Provincial Consultative Council on Statistical Policy, scheduled to hold its inaugural meeting in late 1974, where members would set out the terms of reference for future cooperation. The seed for such a committee had been planted a few years earlier. In April 1971, a discussion paper prepared for the May 1971 advisory committee meeting of the Federal-Provincial Conference on Economic Statistics and other conferences and committees suggested that a council on statistical policy be created along with a series of statistical committees to continue the work of existing committees under the same or similar terms of reference. A few years later, in May 1973, at another meeting of the Federal-Provincial Conference on Economic Statistics, agreement was reached to broaden the terms of reference to embrace all fields of statistics, and to restructure the Council's composition and procedures so as to permit more effective consideration of broad policy questions. The first meeting of the Federal-Provincial Consultative Council on Statistical Policy was held in November 1974. In May 1974, letters of explanation and the proposed terms of reference were sent to the premiers of all provinces and the commissioners of the territories. Initially, there was a wide disparity of interest. However, the response regarding whether to form the council was unanimously in favour, and one delegate was appointed to represent each government on the Council. Nunavut's separation from the Northwest Territories in 1999 instigated the shift in the name of the committee to become inclusive of the territories in 2000. The overarching committee is known in 2018 as the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Consultative Council on Statistical Policy.

One particular federal-provincial agreement in the spring of 1972 resulted in the Gross National Product Division undertaking a research program aimed at estimating the provincial distribution of total Canadian gross domestic product (GDP). A joint review with the provincial statistical offices and other federal departments was under way, as part of a continuing project with the Federal-Provincial Committee on Provincial Economic Accounts, to address challenges of concepts, methodology and data sources. By 1976/1977, annual GDP for the provinces and territories was completed on an experimental basis for the period from 1961 to 1974. This work was indeed promising and would evolve to take root in a much larger way 15 to 20 years later. A revision of measures relating to real domestic product for 1961 to 1971 was also completed, which allowed the Industry Product Division to proceed with a 1971 reference-based publication with continuous production data by industry going back to the mid-1930s. Discussions were also initiated with provincial statistical offices to conduct joint surveys on capital and repair expenditures.

The Computer Centre operates around the clock

Word processing equipment was beginning to be used to improve and expedite general typing. There were five typing and transcribing units at Statistics Canada in the early 1970s, as well as an in-house terminal network with about 150 terminals where users could remotely enter their computer jobs, develop programs, and edit text. A study on the feasibility of capturing data in machine-readable form with Optical Character Recognition equipment was conducted. In 1973, the agency's computer system was an IBM S370/165 with core capacity of 2 million bytes and a disk storage capacity of 3.6 billion bytes. By the next year, this capacity had grown to 3 million bytes and 5.2 billion bytes of storage; even so, the agency could not keep up with the demand and needed to purchase computer resources from outside. As it was, the computer centre operated around the clock Monday to Friday (3 shifts on a 24-hour basis), and eight hours a day on weekends and holidays. Dual disk-drive mini-computers were installed in the eight regional offices to be used initially as a data-gathering and transmission system for the Labour Force Survey. Data capture was quickly moving away from punched cards toward the direct capture of data on magnetic disk and tape. Greater automation was permitting reduced lag in response to requests for data, and allowing more data to be released more quickly. In fact, by the mid-1970s, Trade Statistics publications were almost entirely produced by word processing, although there was a great deal of resistance to full computerization of publications on the part of more conservative divisions.

Notable milestones in the statistical program

Key releases on government finance and the System of National Accounts

In 1973/1974, the agency was developing standard accounts classification frameworks for government financial transactions, as well as participating in a federal interdepartmental committee on the classification of federal revenue, expenditure, and asset and liability transactions, and in an OECD workgroup to develop a standard international framework. March 1975 marked the first release of Government Finance in Accordance with the System of National Accounts, which was developed to facilitate current analysis of the government sector. The release presented revenue and expenditure detail for all subsectors of the government by quarters for the years 1970 to 1973.

The year 1975 would also mark the publication of comprehensive documentation on Canada's System of National Accounts, which were a vital reference source for economists in a world where most information was still paper-based. This was a three-volume series, the first volume presenting a complete record of the annual income and expenditure accounts estimates for the years 1926 to 1974; the second giving quarterly estimates for the years 1947 to 1974; and the third containing a thorough explanation of definitions, concepts, data sources and methods relating to the income and expenditure accounts.

Trade statistics

One of the milestone achievements of the early 1970s was that Canada and the United States began talking the same language in merchandise trade statistics. This resulted from the work of a Canada-U.S. Trade Statistics Committee, which assembled a framework for reconciling, harmonizing, and monitoring counterpart trade statistics in 1971. The two countries completed a reconciliation of the current account of the balance of payments, including receipts and payments for services and transfers in addition to those for merchandise trade. This was an important step in paving the way for the eventual elimination of differences in trade information published by the two countries. A paper on the topic was written in collaboration with the U.S. Census Bureau and was presented at the 18th session of the United Nations Statistical Commission. This work was the beginning of an ongoing reconciliation program and would also spawn the beginning of similar work with other trading partners.

Seasonal adjustment and time series analysis

The development and management of CANSIM was continuing, although access was still available to federal departments and agencies only through remote terminals. A new computer-based econometric model called "Candide" was developed to assist economists and statisticians in forecasting medium-term economic trends. One of the first uses of the model was made by the Economic Council of Canada to develop economic projections to 1980. Work was also progressing on seasonal adjustment—a new seasonal adjustment technique was developed for the Labour Force Survey in 1974/1975. By 1977/1978, the well-established Seasonal Adjustment and Time Series Analysis staff in the Current Economic Analysis Division were developing fundamental research in the field of seasonal adjustment and time series analysis.

The agency makes its mark in seasonal adjustment

Dr. Estelle Bee Dagum was a Statistics Canada employee from 1972 to 1993. She rose to the directorship of the Time Series Research and Analysis Division, a position she held for 12 years. In 1980, she was the first-ever recipient of the Washington Statistical Society's Julius Shiskin Award for outstanding work in economic statistics. The award was established in honour of one of the most respected statisticians in the United States, who began experimenting in the 1950s with computer programs to seasonally adjust data. His twelfth experiment, which he called "X-11" (his first was X-0), was the most successful; however, it did not identify major changes in trends and cycles fast enough. Meanwhile, work at Statistics Canada on short-term forecasting with auto-regressive integrated moving averages (ARIMA) had been progressing. The ARIMA principles had been worked out in the 1940s and 2 U.K. statisticians had automated the method in 1970. Dr. Dagum developed a combined X-11-ARIMA seasonal adjustment method, which as a result became the fastest and most reliable method for discovering major changes in trends in activities that varied seasonally. The method was first adopted in 1975 for the seasonal adjustment of the Labour Force Survey, and established Statistics Canada as a leader in the field of seasonal adjustment. In 2000, Dr. Dagum also received the Career Excellence Award.

A new emphasis on social statistics

Dr. Ostry's task force report had also indicated a need for increased emphasis on the development of concepts and unifying frameworks for social statistics and social indicators. Government priorities included a new emphasis on social and environmental problems, but social scientists had not yet succeeded in developing social models analogous to economic models to aid in the process of decision making. A significant revision and expansion of the Labour Force Survey was already under way, marking the first complete overhaul of the survey since its launch in 1945, and was set to come to fruition in 1976. The expanded survey would respond to demands for new and more comprehensive labour market data, including a larger sample to provide more reliable data at levels such as the provincial and sub-provincial levels, and with more detailed cross-classifications. The monthly sample would increase from 35,000 to 55,000; by 1977/1978, it would grow to about 62,700 households. A new pilot was also undertaken to study the feasibility of conducting the survey on Indian reserves. An investigation was under way into the use of administrative data for labour programs and into the development of a long-range statistical program on employment, earnings and hours.

A social statistics research program was in its infancy at the agency and included the production of a compendium of statistics highlighting social concerns in Canada—which would become Perspective Canada, first published in the fall of 1974. The compendium was to help address the growing demand for social indicators, and to serve as an aid in assessing the relevance and limitations of existing statistics in the social realm. The research program was to increase the focus on individuals and their passage through their life stages, institutions that influenced that life passage, as well as the physical facilities created and maintained for the benefit of the individual. A social statistics field, covering labour, personal finance, health, social security, education, science, culture and justice, would later be created, in 1979/1980.

One of the new publications in 1972 was Pension Plans in Canada, a series based on an administrative data bank created with the co-operation of the Federal Department of Insurance and the provincial authorities of Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Tabulations were then run for the participating federal and provincial pension commissions. The publication was so popular that the first publication required two reprints to meet demand, and more provinces were eventually added to the series.

These were also the formative years for demographic projections. A model initially developed for Ontario at the Institute for Quantitative Analysis of Economic and Social Policy at the University of Toronto was subsequently modified for national application. The agency provided inputs to the model to simulate changes in population composition over time. One of the major new publications for 1974 was a series of official Population Projections for Canada and the Provinces, 1972-2001, by age and sex. The following year, a technical report would be published as well as population projections for households and families. Thereafter, similar projections would be published every five years. As part of the population estimates program in 1976/1977, an improved methodology using family allowance records was used to estimate interprovincial migration for the 1961-to-1976 period.

Human Activity and the Environment is born

An interdepartmental committee was established and directed by the Senior Advisor on Integration to plan and monitor the development of environmental data. In 1974/1975, the agency initiated a conceptual framework for environmental data, as well as a handbook on environmental data—which would be released in 1978/1979 as the first Human Activity and the Environment publication.

International Women's Year

The public service had established an Office of Equal Opportunity for Women in 1971, which coordinated equal-opportunity programs and emphasized that all public service careers were accessible to both women and men. In fact, in June 1972, the following slogan would appear on job advertisements issued by the Public Service Commission: "This competition is open to both men and women."

The year 1975 was International Women's Year, and federal departments and agencies were encouraged to propose ways in which they could contribute to the celebrations. Statistics Canada published an analytical study on the changing role of women in the Canadian economy, which was conducted by the CD Howe Research Institute under contract to Statistics Canada. The article was based on an analysis of data published by Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada appointed a permanent Equal Opportunity for Women (EOW) committee, and a full-time EOW coordinator in the personnel division.

A general system of editing and imputation

The Statistical Services Field, created in 1973, supported data collection and compilation operations, including survey methodology, field survey work, and data processing. The merging of systems with methodology made it possible to move from an ad hoc approach to surveys toward more of a centralized approach with agency-wide standards, and fostered the development of more research capacity. For example, a general system of editing and automatic imputation of data based on a principle of minimal change developed by Dr. Fellegi and Dr. Holt was in development for the 1976 Census and was. It was originally called GEISHA (Generalized Edit and Imputation System using the Hot deck Approach) and later renamed CANEDIT, and was used on many other surveys. Fellegi and Holt would publish a landmark paper "A Systemic Approach to Automatic Edit and Imputation" in 1976 in the Journal of the American Statistical Association. Before their ground-breaking work, there had been no unified theory of edit and imputation—ad hoc procedures were generally used. Their minimal change principle was used for many years in government statistical agencies around the world.

The Census Program

In 1973, the newly created Census Field was actively engaged in programs relating to three censuses: processing and publishing the results from 1971, planning for 1976, and long-range planning for 1981. The Census Field pioneered the use of project management in the new matrix organization of the agency. The Field was responsible for the censuses of population, housing and agriculture, as well as regular population estimates and projections, and conducted special surveys, such as the High-qualified Manpower Survey. This survey, based on a sample of university graduates identified by the 1971 Census, was undertaken for the Minister of State for Science and Technology. The Field was also home to the Census Pension Searches Unit, which regularly carried out proofs of age for pension purposes and proofs of birthplace for establishing citizenship. Established in 1973, the Census User Relations Group supported the agency's direction in becoming more responsive to the needs of its major clients. Its main function was to plan and maintain effective public relations programs with its users and to coordinate client requests.

Five years of research began paying dividends in 1973, when geocoding began to be used, with information sourced from the 1971 Census, including data on population, age, marital status, mother tongue, and housing. This was a system that enabled data production on pre-determined geographical areas of all sizes, including small customized areas. The geocoding system was offered as a statistical service to supply detailed data for user-specified areas. Furthermore, components of the system were available to organizations with the computer capacity to geocode their own data files.

Wage and price controls

Chapter 1 introduced the commencement of stagflation in the early 1970s, denoting an economic situation where inflation was high and economic growth was slow. Inflation grew from about 3% in 1970 to over 12% just three years later. Many workers demanded wage increases. While some employers granted them, others did not, and workers often went on strike. In 1975, the government passed an Anti-Inflation Act and created an Anti-Inflation Board (AIB). The Board would monitor movements in prices and wages, and had the legal power to regulate the price / wage decisions of businesses. It sought to ensure wage growth was in line with targets of 8%, 6% and 4% over a 3-year period. It limited pay increases for federal public employees and those in companies with more than 500 employees. The Act was quite contentious as it was seen as government intrusion into the free market economy. The price and wage controls were enforced until 1978, and the Act was repealed in 1979. The AIB was not overly fond of the consumer price index (CPI) as a measure of inflation. In fact, its third-year report, in 1978, would state that "excessive reference to the total CPI is disturbing because this can only foster unjustified pessimism about future inflation rates in Canada at a time when most other indicators suggest that such views are unwarranted." Since the CPI was being used as a broad indicator of inflation and a bargaining tool in wage contracts, among other uses, it was also amended so that it would represent all families in urban centres of 30,000 or more, regardless of income or family size. As amended, the Act reflected overall consumer price change, rather than the price change experienced by a subset of households.

However, the CPI was not the only price index of the day. A number of new price indexes, including a number of construction price indexes were being developed in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. There were also wholesale and retail price indexes, export and import price indexes, and a system of industry-classified price indexes called the Industry Selling Price Indexes. It was a busy time for the Prices Division, as it seemed that, every year, more and more indexes were being developed or revised. The General Wholesale index was apparently in wide demand in the early 1970s, despite its 1935-to-1939 period and its weight base. In 1973/1974, examples of new indexes included an index of physicians' fees and an index of bus industries.

In June 1978, the Centre for the Study of Inflation and Productivity, which was known as "the son of the Anti-Inflation Board," was established as an agency of the Economic Council of Canada to analyze and monitor price and cost developments and conduct a comprehensive research program. It was also to monitor what was called the "CPI-2," that is, CPI excluding the highly volatile food items. It would be terminated less than a year later, in March 1979. It was replaced by the National Commission on Inflation, which was far less powerful than the AIB, but could require firms to provide information on wages, price and profit increases. Overall, while the controls likely reduced wage increases by a few percentage points, neither they nor monetary or fiscal policy were restrictive enough to maintain a lower rate of inflation.

The agency began publishing seasonally adjusted CPI on an annual basis in 1975 and then, as statistical software improved, on a monthly basis. The division would also complete a revision in 1978/1979, the eighth such revision in the history of the Canadian CPI, this particular one updating the consumer expenditure patterns from those of 1967 to those of 1974. The Prices Division was also conducting a feasibility study of producing a CPI for smaller centres, and was focused on Maritime cities including Charlottetown and Summerside. City CPIs were first published in 1974 (for years beginning in 1973) for Saskatoon, Regina, Edmonton and Calgary. By 1975/1976, the CPI was being expanded from 14 sample cities to approximately 50. In addition, the agency began calculating Canada-level indexes as a weighted average of the indexes for the urban centres. One important result of this was an increased timeliness—as by 1978-79, the agency was able to release simultaneously both the national and city CPI estimates, effectively doing away with a previous 10-day lag between the two sets of data.

Inflation continued to rise rapidly, and a second oil shock occurred as world oil prices once again rose when the Iraq-Iran War broke out in 1979. The average annual CPI inflation would reach a high of 12.5% in 1981, and questions were beginning to surface about the validity of the CPI.

Don't shoot the messenger

The CPI was continually being questioned as a reliable measure of inflation. In 1978/79, the officers of the Prices Division gave more than 25 seminars and public presentations across the country on the CPI and its revision to government officials, labour unions, and other interested parties. As the harbinger of news on the inflationary front, the Agency proactively undertook an extensive review, evaluation and analysis of the concepts and methodologies of price measurement in the fall of 1981, it's "Price Measurement Review Program." Three symposia were held to bring together Canadian and foreign experts to discuss aspects of price measurement and the inflation process. As well, national consultations on price measurement were held in early 1982 with business and academic communities, federal and provincial governments, and consumer groups. These provided a public forum for in-depth analyses of concepts and methodologies associated with the CPI and other measures of price change. The findings from the symposia and consultations also provided a basis for ongoing research on price measurement issues and future developments in the program. The findings were presented by specialists of national and international reputation at a two-and-a-half day public conference on price measurement in November 1982 in Ottawa. A Price Measurement Advisory Committee was established at the time of the conference, and began work in 1983 to review concepts, methods, and priorities of the agency's measures of price change. The committee continues to provide advice to the agency on price measurement to this day.

A new Chief Statistician is appointed

When Dr. Ostry was re-assigned in 1975 to the Department of Corporate and Consumer Affairs as Deputy Minister, she was succeeded by then-Assistant Chief Statistician of Economic Accounts and Integration Dr. Peter Kirkham. While two and half years was a short time period, it was not necessarily an anomaly to rotate deputy ministers after short time periods. It is also worth noting that Dr. Ostry was a high-flyer and that the government apparently wanted her expertise at the Department of Corporate and Consumer Affairs to assist with the legislative hurdles of amendments to Canada's new competition legislation.

Dr. Ostry had successfully shaken up the agency, she brought in "new blood" (which would become a slogan of the times and perhaps still is), and she ushered in an era of being more open with respect to communications between the Chief Statistician and her directors. It is worth noting that in probing for the reason for her relatively short stay, those who were close to her indicated that she was not overly fond of administration or management. It is also said that she may have dropped hints to the Clerk of the Privy Council at the time that she thought the Prime Minister had got hold of a very good initiative to see that Deputies were moved around. Ultimately, her talents were highlighted and perhaps better used in her position at the OECD, and particularly later on, as the Prime Minister's sherpa.

Dr. Kirkham did not take on the position of Chief Statistician at an easy time. The balance of Dr. Ostry's changes had not yet come to fruition, with the dust not quite yet settled after such a large organizational shift. In a mere 2.5 years, the agency had adopted a cost-recovery program, expanded its marketing and communications program, increased its outreach program, and brought in a wealth of new staff from the outside world.

Dr. Peter Gilbert Kirkham

Dr. Peter Kirkham was a graduate of the Royal Military College of Canada, and served in the Armed Forces as an engineer from 1953 to 1961. He also had a degree in civil engineering from the University of British Columbia, Masters' degrees in economics and business administration from the University of Western Ontario, and a Doctorate in economics from Princeton University. Before joining the agency in 1973, he worked as an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario's School of Business Administration. He was Assistant Chief Statistician responsible for Economic Accounts and Integration before being appointed as Chief Statistician and served in that role from 1975 to 1980. After leaving the Agency in 1980, Dr. Kirkham was appointed Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the Bank of Montréal. He retired in 1992, and currently lives in Kingston, Ontario.

The applecart overturns

Brewing morale and management problems at the agency spilled into the public sphere in 1975, when a 27-year veteran and senior executive of the agency distributed a rather scathing 18-page memo upon his retirement, criticizing the "disconnected management style" of senior management, placing much of the blame on Dr. Ostry and Dr. Kirkham. By 1976, criticisms progressively began to appear in the media and in the House of Commons, and from past and present staff members. Statistics Canada was accused of poor management, poor methodology and statistical standards, poor integrity, and poor sensitivity to user needs. The perception of the agency steadily deteriorated, and with the agency lacking a clear policy on media relations, these were difficult to navigate waters. At the time, the media relations approach was to sit tight and hope that the negative attention would soon pass. Public confidence was lacking and morale at the agency was at an all-time low.

One of the contributing factors to such a disconnected agency may have been that management had few means to gauge what employees were thinking or how they were faring. The annual employee performance review system required each supervisor to complete a detailed form describing duties and necessary abilities, and assessing their employees' performance against these. Supervisors were reluctant to "offend" their employees in case they launched formal grievances. The system was not well-liked.

In an interview with the staff newspaper, Dr. Kirkham spoke of the size of the agency as a contributing factor to the low morale. The agency had quadrupled in size since 1960, and it was hard to develop personal contacts in such a large organization spread out over 8 buildings. In fact, the agency had grown from 1700 people and a budget of $7.4 million in 1960 to more than 5,700 people and a budget of $100 million in 1975. He also spoke of management issues such as the need for clearer goals and objectives, and the ongoing work to develop medium term plans. Dr. Kirkham noted that historically, when the agency was smaller, it was able to operate in the oral tradition, and each person was aware of the decisions taken and broad objectives of the agency. With technical and social changes, there was an explosion of demand for information, which instigated the growth and change of the Bureau. However, this growth happened without the managerial mechanisms and procedures required for the operation of a larger organization.

Public perception continued to decline in 1976 when it came to light that four employees were found to have breached conflict of interest guidelines by what was called "moonlighting" by operating a private company which had started consulting and customizing data for sale starting in 1971. Conflict of interest guidelines had been imposed by the government in 1973, requiring employees to disclose any interests that might conceivably be construed as being in actual or potential conflict with their duties. When Dr. Ostry was made aware of the employee activities in 1974, the RCMP had been called immediately to conduct a full investigation of the matter, including appearing early one morning to remove boxes of papers from an employee's house. They found that while the employees' conduct was not illegal as they had used only publicly available data, the situation comprised a conflict of interest and was professionally unethical.

The agency was also under fire for its hiring and promotion practices in connection with the conflict of interest guidelines, with eyebrows raised at its supposedly high number of married couples—these concerns garnered significant press although an audit by the Public Service Commission found no irregularities. The Minister responsible for Statistics Canada at the time the information became public was the Honourable Jean Chrétien, Minister of Industry, Trade and Commerce, who asked Dr. Kirkham to investigate all external contracts entered into by Statistics Canada employees. As a result of these incidents, Statistics Canada would go on to clarify and strengthen its conflict-of-interest rules in 1978.

Opposition parties and the media were active in criticizing the advance release practices of the agency, as well as the practice of census hiring. While work on a pre-release policy had begun under Duffett in 1971, a revised and strengthened policy statement was issued in 1974 to ensure new statistics were available to all users simultaneously in order to avoid any possibility of privilege. The policy also clearly laid out the conditions for pre-release of information. However, the practice of providing advance access to ministers was still widely criticized.

With respect to census hiring, the current Statistics Act permits the Minister to assist in the recruiting of field interviewers, including for the Labour Force Survey, the CPI, business surveys, and censuses. The process at the time was that, when the regional offices identified the need for new interviewers, they would contact head office who would contact the Minister's staff to determine whether any candidates would be recommended. When head office received a list from the Minister's office, they would relay the information to the regional office, which would contact, interview and test each person. This was obviously not an ideal situation, given the potential for political influence and preferential treatment. This practice was also widely criticized by opposition parties, who saw it as a way to distribute favours to party supporters. Today, while the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada retains this authority, it is not exercised.

Organizational changes

In the fall of 1976, the Departmental Secretariat was established and charged with co-ordinating the flow of correspondence to and from the Chief Statistician's office, including parliamentary returns. It was responsible for documenting issues, developing policy proposals to the Executive Committee, and ensuring action on the Executive Committee's decisions. It also provided research, administrative and staff support to the Chief Statistician.

Statistics Canada's Operational Audit Division was also first established in 1976, and was first staffed under contract by the Audit Services Bureau of Supply and Services Canada, with Statistics Canada personnel joining the division 18 months later. It carried out financial and operational audits, as well as efficiency reviews and special studies. In 1978/1979, a total of 22 audits were conducted.

Metrification

The agency was also in the midst of converting to the metric system, or "metrification." In May 1973, the staff newspaper (SCAN) included an article ominously entitled "The switch to metric measurement is coming and you will be affected." The federal government was implementing the recommendations of its white paper of 1970 on metric conversion in Canada. The SCAN article included a primer on conversions and covered some of the challenges facing the agency as it made the changes required to its systems and questionnaires. Preliminary work on the impact of metrification was carried out by the new Standards Division, established in 1973, whose responsibility it was to control classifications and concepts for the agency. Practical implementation of the metric system at the agency started in 1977, the first stage being the conversion of publications to show quantities in metric, and the second being to provide a metric option in survey questionnaires for one year, before converting questionnaires to express only metric units.

Canada's conversion to the metric system

Canada's metrification first went through a period of "soft" conversion, where quantities were expressed in both imperial and metric measures. Container sizes and specifications changed, even for things like toothpaste, shampoo, and pharmaceuticals. As of April 1, 1975, temperatures started being expressed in Celsius only, and, as of September 1, 1975, precipitation was given in millimetres. Metrification affected everything, from road transport, to hospital functions, to the grain trade, and the food and beverage industry.

Substantial benefits were expected by the conversion to the metric system in Canada, including in the area of international trade since about 90% of the world's population was using the metric system or was well on its way to conversion at the time.

Re-organization and decentralization