Workers’ experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, sexual assault and gender-based discrimination in the Canadian provinces, 2020

by Marta Burczycka, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- Just under half (47%) of workers in the provinces either witnessed or experienced some sort of inappropriate sexualized or discriminatory behaviour in a work-related setting in the previous year—that is, in a place where they performed work activities for their job or business, or interacted with people associated with their work. This time frame reflects the months just prior to large-scale impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on workplaces.

- One-quarter (25%) of women said that they had been personally targeted with sexualized behaviours in their workplace in the preceding year, along with 17% of men. Women who had been targeted usually said that a man was always responsible, including 56% of those who experienced inappropriate communication, 67%E of those who experienced being exposed to sexually explicit materials, and 78% of those who experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations.

- One in ten (10%) women experienced workplace discrimination based on their gender, along with a smaller proportion of men (4%). Most women who had experienced this form of discrimination said that the perpetrator was always a man (60%), while men were as likely to say that the perpetrator was always a man (33%) or always a woman (33%).

- For women, personal experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviour were most common for those working in certain occupations historically dominated by men. Almost half (47%E) of women working in trades, transportation, equipment operation and related occupations experienced these behaviours at work in the past year.

- Among women working in certain occupations that have historically been filled by women, those who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour often said that at least one incident had been perpetrated by a customer or client. This was the case for 53% of women working in sales and service occupations who had been targeted.

- Behaviours related to the display of sexually explicit materials often occurred by phone or online, during interactions between people associated through work. Almost one quarter (23%) of workers who experienced this kind of inappropriate sexualized behaviour said that it had happened online or by phone, including 23% of women and 23% of men who had experienced it.

- Significant proportions of women and men experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours perpetrated by a person in authority, such as a supervisor or boss. Depending on the type of behaviour experienced, these proportions ranged from 22% to 28%E among women and 21% to 30% among men who had been targeted.

- Among women targeted with discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation, 44% identified someone in authority as responsible. The same was true for 36% of men who had experienced this type of discrimination.

- Although all workplaces must comply with anti-harassment and discrimination laws, 32% of women and 26% of men said that their employer had not provided them with information on how to report sexual harassment and sexual assault.

- One in eight (13%) women stated that they had been sexually assaulted in a work-related context at one point during their working lives, about four times the proportion among men (3%). For women, sexual assault in the workplace often took the form of unwanted sexual touching, experienced by 13% of women who had ever worked.

- Among women who had experienced sexual assault in a work-related setting in the previous year, 31%E stated that the perpetrator had been a client, a patient or a customer, while 28%E identified someone in a position of authority.

- As with other forms of victimization and misconduct in other settings, inappropriate sexualized behaviours and gender-based discrimination at work were more common among young people, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ2 people.

- Some variation in the prevalence of inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination in the workplace was noted between provinces, and between workers who lived in rural areas versus population centres.

In Canada, the right of individuals to pursue employment opportunities and benefits—regardless of genderNote —is protected under the Employment Equity Act. Over time, public policy has come to acknowledge that women’s full participation in the labour force is vital for the well-being of individuals, families and society as a whole. Despite these advancements, inequality in some sectors of the labour market has persisted: from the wage gap to discriminatory hiring and layoffs, women are often at a disadvantage when it comes to equal participation in the workforce and the economy (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2018; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2020).

Canadian federal, provincial and territorial governments have also recognized the negative impacts of sexual harassment in the workplace. Laws such as the Canadian Human Rights Code and legislation enacted by each province and territory aim to protect people from gender-based harassment at work. Despite these protections, widely-publicized accounts such as those associated with the #MeToo movement make clear that women continue to experience gender-based discrimination and inappropriate sexualized behaviours that can make them feel undervalued, uncomfortable and unsafe while at work. These experiences—ranging from sexual jokes and comments to unwanted physical contact to sexual assault—can profoundly impact women’s labour force participation and opportunities. Women’s choices and economic success may be limited by these experiences and their physical and psychological well-being can suffer, affecting their lives and the lives of those close to them (Berdahl and Raver 2011). Furthermore, when sexualized and discriminatory behaviours are present in an organizational setting, they can normalize stereotypes and reproduce them on a systemic scale; this takes on particular importance when sexualized behaviours and discrimination are present in the workplace, where women and others continue to experience inequities in relation to opportunities, advancement and pay (Hershcovis et al. 2021).

Unequal access and opportunities in the workplace also affect those who identify as an immigrant, a member of a designated visible minority group, an Indigenous person (First Nations person, Métis or Inuit), a person with a disability, with a sexual orientation other than heterosexual, or with a gender other than the one assigned at birth. Members of these groups face other forms of discrimination when it comes to labour market participation and income, and those who identify as women are especially vulnerable (Office for Economic Cooperation and Development 2017). How inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination based on gender, gender identity and sexual orientation affect members of these marginalized groups is therefore of particular importance.

In 2020, for the first time, Statistics Canada conducted the Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work (SSMW). The development and collection of this survey was funded by the Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) as part of the 2017 Federal Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence. Implicit in this strategy is a focus on reducing the risk of violence experienced by women and others; to that end, an understanding of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, discrimination and sexual assault in the workplace is key.

This Juristat article uses data from the 2020 SSMW to explore the nature and prevalence of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, discrimination and sexual assault in Canadian workplaces (see Text box 1 for a detailed list of behaviours measured by the survey). In looking at inappropriate behaviours in the workplace, the survey examined events that occurred in and around the physical work location (or lodging provided by the employer), and included events that occurred electronically or by phone between individuals related through work or business. In addition, incidents that took place during work-related travel, training, or social events that involved co-workers or clients are also included.

The characteristics of those who experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours, gender-based discrimination or sexual assault in the past 12 months and of the workplaces where they happened are explored, to gain an understanding of who is most at risk. The impacts and consequences of these situations are examined, including analysis of what kinds of actions women and men took in response to what happened.Note Additionally, information on workers’ perceptions of the policies, procedures and services in place at their work are presented.

It should be noted that the global COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed how many Canadians work, with 39% having worked virtually from home as of June 2020, compared to 17% before the pandemic (Zossou 2021). As a result of these changes, there has also been a significant shift in how people interact with colleagues and clients, and the impacts of these shifts differ for women and men.Note The majority of information that the SSMW collected from Canadians was gathered in the weeks just prior to the onset of workplace shutdowns in some regions. Thus, data collected and the analysis presented here mostly reflect the experiences of workers before the pandemic.

Throughout this article, the experiences of women will be compared with the experiences of men for a gender-based analysis, and gender-disaggregated data will be provided throughout. Where sample size permits, analysis will incorporate various socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., age, Indigenous identity, immigrant status, visible minority status, disability, religion, language, sexual orientation, marital status, urban or rural residence) in order to explore the intersection of vulnerabilities in the context of workplace experiences.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

How the

Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work measures inappropriate sexualized

behaviours, discrimination and sexual assault

The 2020 Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work collected information on inappropriate sexualized behaviours, discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity and sexual orientation, and sexual assault that happened in a work-related setting. A work-related setting is defined as any place where a person performs work activities for their job or business, and includes:

- At a worksite or in an office building

- In a parking lot or an outdoor space associated with the workplace

- At lodging provided by work

- During work-related travel

- During an activity or a social event with co-workers, supervisors or anyone associated with work (e.g., contractors, consultants, clients, customers, patients)

- At a training session or other event organized by work

- While online or over the phone where some or all of the people are associated with work (e.g., co-workers, supervisors, contractors, consultants, clients, customers, patients)

The survey measured 15 inappropriate sexualized and discriminatory behaviours:

Behaviours related to inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication

- Sexual jokes

- Unwanted sexual attention

- Inappropriate sexual comments

- Inappropriate discussion about sex life

Behaviours related to sexually explicit materials

- Displaying, showing, or sending sexually explicit messages or materials

- Taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos of any co-worker without consent

Behaviours related to unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations

- Indecent exposure or inappropriate display of body parts

- Repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relations

- Unwelcome physical contact or getting too close

- Offering workplace benefits for engaging in sexual activity or being mistreated for not engaging in sexual activity

Discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation

- Suggestions that a man or woman does not act like a man or woman is supposed to act

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are a man or a woman

- Comments that people are either not good at a particular job or should be prevented from having a particular job because they are a man or a woman

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation

- Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are, or are assumed to be, transgender

Throughout this article, the terms “at work” and “the workplace” will be used to denote any of these settings, unless otherwise specified.

In addition, respondents were asked if they had been sexually assaulted in a work-related setting. Sexual assault includes:

- Sexual attacks: include being forced into, or having someone attempt to force into, unwanted sexual activity through being threatened, held down or hurt in some way.

- Unwanted sexual touching: include unwanted touching, grabbing, kissing or fondling.

- Sexual activity where a person is unable to consent, because they are coerced, manipulated, intoxicated or forced in another non-physical way.

End of text box 1

Inappropriate sexualized behaviour and gender-based discrimination in the workplace

Just under half of workers witness or experience inappropriate sexualized or discriminatory behaviour

Just under half (47%) of Canadian workers either witnessed or experienced some sort of inappropriate sexualized behaviour or gender-based discrimination in a work-related setting in the year preceding the survey—that is, in a place where they performed work activities for their job or business, or interacted with people associated with their work. Overall, being exposed to sexualized or discriminatory behaviour in these ways was as common for women (48%) as it was for men (47%).Note These findings suggest that many Canadians—irrespective of gender—work in environments where inappropriate sexualized and discriminatory behaviours are common (Table 1).

Inappropriate sexualized behaviours include behaviours related to inappropriate verbal and non-verbal communication, sexually explicit materials and unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations (see Text box 1). Equal proportions of women (44%) and men (44%) witnessed or experienced some form of these sexualized behaviours at work in the previous year. This overall similarity between women and men was driven by rates of inappropriate communication—the most common of the three categories of sexualized behaviours—which was as commonly reported by women (42%) as men (43%). Inappropriate communication includes sexual jokes, unwanted sexual attention, inappropriate sexual comments and inappropriate discussion of sex life.

Sexual jokes largely drove the similarities in the proportions of women and men who witnessed or experienced inappropriate communication―and in turn, inappropriate sexualized behaviours overall. Sexual jokes were witnessed or experienced in a work-related setting by about four in ten men (39%) and women (36%, a difference not found to be statistically significant). Aside from sexual jokes, all other behaviours related to inappropriate communication were more commonly witnessed or experienced by women workers: unwanted sexual attention, for example, was twice as common among women (16%) than men (8%).

Many Canadian workers also witnessed or experienced discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Gender-based differences were notable, with one in four (25%) women compared to about one in five (19%) men having witnessed or experienced this type of discrimination in a work-related setting. Women were more likely to have witnessed or experienced someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because they are a woman (14%, versus 5% of men). Men, in turn, were slightly more likely than women to have witnessed or experienced someone in the workplace being insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because they are a man (5%, versus 3% of women).

One in four women were targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour at their workplace

While many Canadians worked in environments where they witnessed or experienced inappropriate sexualized or discriminatory behaviours, fewer were personally targeted with these behaviours and here, notable differences were observed between genders. Personal experiences of targeted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours were substantially more common among women workers (28%) than among men (18%; Table 2). Although a workplace where employees are exposed to “causal sexism” in the form of sexualized or discriminatory behaviours can negatively affect workers even indirectly, being personally targeted by these behaviours can have especially difficult consequences (Berdahl and Aquino 2009).

One-quarter (25%) of women workers said that they had been personally targeted by inappropriate sexualized behaviours in their workplace in the preceding year, while the same was true for 17% of men. Among these behaviours, all of those related to inappropriate communication in the workplace were more likely to have been experienced by women: 16% of women experienced sexual jokes, 12% experienced unwanted sexual attention, and 9% experienced inappropriate sexual comments or inappropriate discussions of sex life (respectively). These experiences were less common for men in the workplace (12%, 2%, 4% and 6%, respectively).

Men usually the perpetrator when women are targeted by workplace sexualized behaviour

Most often, women who were targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour in the workplace indicated that a man had been responsible. More than half (56%) of women who had experienced inappropriate communication, 67% E who had experienced being exposed to sexually explicit materials, and 78% who had experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that in all cases, a man had perpetrated the behaviour (Table 3).

Men who experience inappropriate physical contact at work report both men and women as perpetrators

Among men who were targeted, a majority (66%E) who had experienced exposure to sexually explicit materials said that other men were always responsible. However, half of men who experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that it had always been perpetrated by a woman (51%). In contrast, men who experienced inappropriate communication were more likely than women to say that a combination of men and women was responsible (49%; Table 3).

Women more often targeted by gender-based discrimination at their workplace

As with inappropriate sexualized behaviours, women workers were more likely than men to state that they had experienced discrimination based on their gender at their workplace (10% compared to 4%; Table 2). Specifically, women were five times more likely to have been insulted, mistreated, ignored, or excluded because of their gender (7% versus 1%), three times more likely to have been told that that they were either not good at a particular job or should be prevented from having a particular job because of their gender (4% versus 1%), and twice as likely to have heard suggestions that they do not act like someone of their gender is supposed to act (6% versus 3%).Note

Most women who had been targeted with discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in their workplace said that the perpetrator was always a man (60%). An additional 30% stated that a combination of men and women was responsible, either for the same instance of discrimination or across multiple instances. Among men who had been targeted, almost identical proportions said that the perpetrator was always a man (33%), always a woman (33%), or involved men as well as women (32%, differences not found to be statistically significant; Table 4).

Most workers who experience inappropriate sexualized behaviours say they happened at the worksite itself

Many workplaces have codes of conduct meant to prevent inappropriate sexualized behaviours from happening on their premises; these practices are mandated by provincial and territorial legislation (for example, see Ontario Human Rights Commission n.d. (a)). Despite this, about half of workers reported receiving information on this issue from their employer: 56% of men and 49% of women said that their employer had given them information on what constitutes sexual harassment and sexual assault (see Table 7). In turn, the worksite itself was most often the location of inappropriate sexualized behaviours that occurred in a work-related setting; this includes a worksite or office building, a parking lot or outdoor space, or lodging provided by the employer. For example, almost nine in ten women (88%) and men (88%) who experienced behaviours related to inappropriate communication—the most common type of behaviour experienced by workers—stated that at least one instance had happened at the workplace itself (Table 3).Note

One-fifth of workers say some inappropriate sexualized behaviours happened away from the worksite

Inappropriate sexualized or discriminatory behaviours targeting gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that are perpetrated by colleagues, clients or business associates can occur outside of the formal work space; they can also take place at a work-related event held in a public or private location like a bar, restaurant, hotel or conference centre. One-fifth of workers who experienced inappropriate communication said that at least once, the behaviour happened in this type of location, including equal proportions of women (20%) and men (21%; Table 3). Similarly, many workers said that a private or public place was the setting of work-related unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations: this was the case for 21% of men and 18% of women who had experienced this type of behaviour.

Some workers who experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour outside of the workplace said that a training session, conference, or work-related social event was taking place at the time. This was particularly notable for women: two-thirds (66%) of women who had been targeted with sexualized behaviour away from the worksite said that it had happened during training, a conference or a work-related social event. This was a considerably larger proportion than among men (49%E; Chart 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Situation in which behaviour occurred | WomenData table for chart 1 Note † | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of workers targeted away from the worksite | standard error | percent of workers targeted away from the worksite | standard error | |

| Happened during training, a conference or a work-related social event | 66 | 9.2 | 49Note E: Use with caution Note * | 11.0 |

| Happened during another work-related situation away from the worksite | 31 | 8.9 | 48Note E: Use with caution Note * | 10.9 |

E use with caution

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||

Chart 1 end

Inappropriate behaviours also happened by phone or online, when communications involved people who were associated through their work (see Text box 2).

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Technology-enabled

inappropriate sexualized behaviours

In the world outside of work, increasing attention is being paid to the problematic side of online and digital communication, where remoteness and anonymity facilitate harassment and psychological abuse in the online environment (Cohen-Almagor 2018). Meanwhile, many workers are seeing in-person contact with colleagues and clients replaced with virtual connections, through phone, email, instant message and online video platforms. In the era of COVID-19 and beyond, many workplaces are transitioning to remote work and increasing their reliance on technology-enabled communication. In Canada, 39% of workers did their jobs virtually from home as of June 2020, compared to 17% before the pandemic (Zossou 2021).

Findings from the Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work predate the COVID-19 pandemic, but nonetheless offer insights into the prevalence of inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in the virtual workplace. Overall, 2% of all Canadian workers said that they had experienced technology-enabled inappropriate sexualized behaviour or gender-based discrimination in their workplace in the year prior to the survey—that is, behaviours or discrimination that happened online or over the phone. These proportions were relatively equal among men (2%) and women (3%; data not shown).

Compared to behaviours that happened in person, those that happened online or over the phone were relatively rare. Among workers who were targeted, 8% who had experienced inappropriate communication, 3% who had experienced suggested sexual relations, and 5% who had experienced discrimination said that at least one instance of the behaviours happened via communications technology (proportions which were similar for women and for men; see Table 3). The exception was behaviour related to sexually explicit materials: almost one quarter (23%) of workers who experienced this kind of inappropriate sexualized behaviour said that it had happened online or by phone, including 23% of women and 23% of men who had experienced it (data not shown). Most likely, this is due to the nature of specific behaviours involved: taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos of any co-workers without consent inherently involves digital media, and digital communication likely plays a role in many instances of displaying, showing, or sending sexually explicit messages or materials.

Notably, four in ten (39%) workers who experienced inappropriate communication via phone or online said that it had been perpetrated by a supervisor or someone with authority in the workplace (data not shown). This was almost twice the proportion of those who experienced in-person inappropriate communication from someone with authority in the workplace (21%). Specific proportions for men and women workers are not available, due to small sample size.

End of text box 2

Experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviour, discrimination vary by occupation

Canada’s workforce is made up of thousands of occupations, and these can be described using the National Occupation Classification (NOC; see Text box 3). For decades, workers and social scientists have noted that many occupations are gendered, and suggested that workers in some jobs—namely, those historically occupied by women—experience lower wages and greater precariousness of work than others (Moyser 2017). Meanwhile, women working in occupations historically dominated by men face high rates of discrimination and sexual harassment (Gruber 1998). In response, some industry associations have developed programs which incentivize employers to enact changes to their workplace culture (for instance, see British Columbia Construction Association 2020). Findings from the SSMW reveal that despite such measures, women in certain occupations continue to experience high rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviours or gender-based discrimination in a work-related setting.Note

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Occupations in Canada’s

workforce

The National Occupation Classification (NOC) provides a systematic classification structure that categorizes the entire range of occupational activity in Canada. Its detailed occupations are identified and grouped primarily according to the work performed, as determined by the tasks, duties and responsibilities of the occupation. Factors such as the materials processed or used, the industrial processes and the equipment used, the degree of responsibility and complexity of work, as well as the products made and services provided, have been taken as indicators of the work performed when combining jobs into occupations and occupations into groups.

The structure and format of the 2016 NOC are based on the four-tiered hierarchical arrangement of occupational groups with successive levels of disaggregation, with broad occupational categories into which are nested major, minor and unit groups. For the purposes of this analysis, the highest level of categorization—the broad occupational categories—is used (see Text box 3 table). For more information on the 2016 NOC, see Introduction to the National Occupational Classification (NOC) 2016 Version 1.3.

NOC data collected through Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey provide information on the relative proportions of women and men employed in various occupations at a given point in time. For instance, in February 2020 (when collection for the Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work was under way), 79% of positions in occupations related to health were held by women; in contrast, 93% of positions in trades, transportation and equipment operation and related occupations were staffed by men (Text box 3 table).

| National Occupational Classification (NOC)Text box 3 table Note 1 | Men | Women | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number (thousands) | percent | number (thousands) | percent | number (thousands) | percent | |

| Management occupations | 1,118 | 65 | 610 | 35 | 1,729 | 100 |

| Business, finance and administration occupations | 971 | 32 | 2,097 | 68 | 3,068 | 100 |

| Natural and applied sciences and related occupations | 1,199 | 77 | 363 | 23 | 1,561 | 100 |

| Health occupations | 298 | 21 | 1,144 | 79 | 1,441 | 100 |

| Occupations in education, law and social, community and government services | 654 | 30 | 1,534 | 70 | 2,188 | 100 |

| Occupations in art, culture, recreation and sport | 246 | 46 | 291 | 54 | 537 | 100 |

| Sales and service occupations | 2,071 | 45 | 2,503 | 55 | 4,574 | 100 |

| Trades, transport and equipment operators and related occupations | 2,453 | 93 | 172 | 7 | 2,624 | 100 |

| Natural resources, agriculture and related production occupations | 258 | 82 | 56 | 18 | 314 | 100 |

| Occupations in manufacturing and utilities | 568 | 70 | 246 | 30 | 813 | 100 |

| Total, all occupationsText box 3 table Note 2 | 9,834 | 52 | 9,016 | 48 | 18,850 | 100 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||||||

End of text box 3

Workers in some jobs historically held by men experience high rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviour, discrimination

Regardless of their occupation, personal experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviour were common for women. Among women working in the five occupation groups where men made up more than half the workforce (see Text box 3), 28% had been targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour at work in the preceding year (data not shown). However, this proportion was close to that reported by women working in occupations where women were the majority (25%, a difference not found to be statistically significant).

Despite this, women working in certain occupations―where men outnumber women historically (see Moyser 2017) and in the present day―experienced considerably higher rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviour at work than other women. For example, almost half (47%E) of women working in trades, transportation, equipment operation and related occupations experienced these behaviours at work in the past year. Large proportions of women working in natural and applied sciences and related occupations (32%) and in occupations related to manufacturing and utilities (29%E) also experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour in the workplace (Chart 2).Note

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Type of occupation | WomenData table for chart 2 Note † | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of workers who experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | percent of workers who experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | |

| Management | 19 | 5.9 | 12Note * | 4.4 |

| Business, finance and administration | 19 | 3.0 | 17Note * | 4.3 |

| Natural and applied sciences and related occupations | 32 | 8.0 | 12Note * | 3.0 |

| Health | 30 | 5.1 | 19Note E: Use with caution Note * | 7.8 |

| Education, law and social, community and government services | 21 | 3.3 | 16Note * | 4.6 |

| Art, culture, recreation and sport | 28 | 8.6 | 15Note E: Use with caution | 8.1 |

| Sales and service | 32 | 4.3 | 22Note * | 4.3 |

| Trades, transport and equipment operators and related occupations | 47Note E: Use with caution | 14.2 | 19Note * | 4.4 |

| Natural resources, agriculture and related production occupations | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 20Note E: Use with caution | 8.8 |

| Manufacturing and utilities | 29Note E: Use with caution | 12.6 | 14Note * | 6.0 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||

Chart 2 end

Similarly, men in some occupations where men historically outnumbered women experienced high rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviours. For example, about one in five men working in trades, transportation and equipment operations and related occupations (19%) and in natural resources, agriculture and related production occupations (20%E) had personally experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours (Chart 2).

Overall, however, men working in occupations historically dominated by women experienced higher rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviours than men working in fields where men were the majority. Almost one in five (19%) men working in the five occupation groups in which women formed the majority personally experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour at work, compared to 15% of men who worked in fields where men formed the majority of workers (data not shown). For example, 22% of men working in sales and service occupations and 19%E of those in health-related jobs had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours in their workplace―proportions that were higher than among men in many other occupation groups, despite being lower than those experienced by women (Chart 2).

Sexualized behaviours perpetrated by clients, patients more common in occupations dominated by women

While overall, women working in the five occupations historically dominated by men had a similar rate of inappropriate sexualized behaviours to those in the five occupations in which women formed the majority, certain occupations within the latter group were the exception. Namely, women working in sales and service occupations—historically among the most common jobs for women (Moyser 2017)—were also more likely to have experienced these behaviours (32%) than women in most other occupation groups (Chart 2).

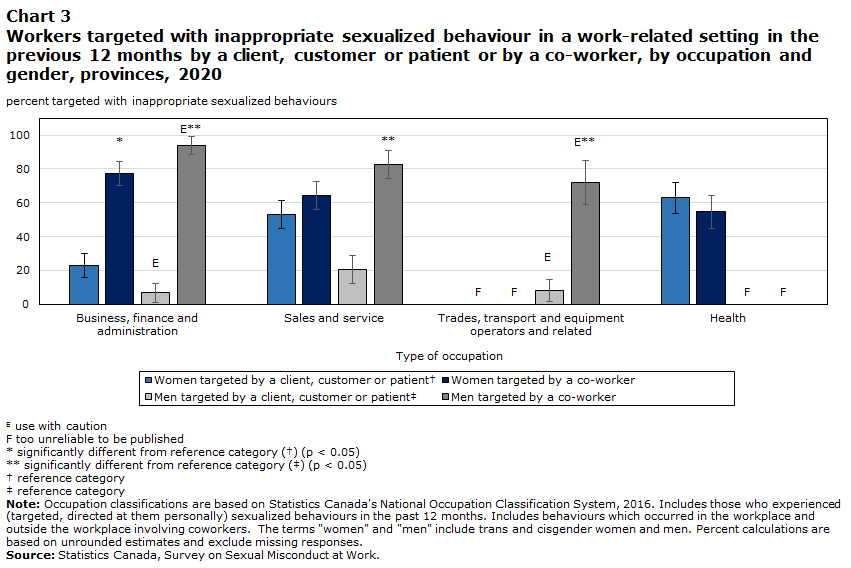

Sales and service work brings women into near-constant contact with customers and clients, and they can spend more of their work hours interacting with the public than with their colleagues: just over half (53%) of women working in these occupations who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour in the workplace said that at least one incident had been perpetrated by a customer or client (Chart 3). As women in these occupations often experienced multiple instances of inappropriate behaviours perpetrated by a variety of people, survey data cannot determine the gender of individual perpetrators; overall, however, 58% of women working in sales and service occupations who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour said that the perpetrator had been a man (data not shown). This proportion was similar to what was reported by women across all occupation groups (56%, a difference not found to be statistically significant).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Type of occupation | Men targeted by a client, customer or patientData table for chart 3 Note ‡ | Men targeted by a co-worker | Women targeted by a client, customer or patientData table for chart 3 Note † | Women targeted by a co-worker | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | percent targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | percent targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | percent targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours | standard error | |

| Business, finance and administration | 7Note E: Use with caution | 5.4 | 94Note E: Use with caution Note ** | 5.1 | 23 | 7.1 | 77Note * | 6.9 |

| Sales and service | 21 | 8.3 | 83Note ** | 8.1 | 53 | 8.3 | 64 | 8.3 |

| Trades, transport and equipment operators and related | 8Note E: Use with caution | 6.5 | 72Note E: Use with caution Note ** | 13.0 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Health | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 63 | 9.2 | 55 | 9.6 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||||||

Chart 3 end

Compared to women, a considerably smaller proportion of men in sales and service jobs who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours said that the perpetrator was a customer or client (21%; Chart 3). Instead, men in this type of work were more commonly targeted by a co-worker (83% of men who were targeted, compared to 64% of women). Regardless of their relationship to the perpetrator, men working in sales and service occupations were no more likely to say that the perpetrator had always been a man or always been woman, compared to men across all occupation types.

Inappropriate behaviours perpetrated by customers and clients may pose particular difficulties for workers in sales and service occupations, and for their employers. For example, some workers may be reluctant to report the behaviour for fear of losing tips from their customers. Additionally, workplace harassment that is perpetrated by individuals other than employees is difficult to target with education campaigns directed at workers.

Further, these findings underscore an important difference between how women and men are treated in the workplace: while all workers in sales and service occupations experience a higher prevalence of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, the nature of those experiences differs. Women’s mistreatment by customers and clients supports observations that the anonymous, public-facing nature of some sales and service occupations emboldens some customers and clients to act in harassing and demeaning ways (Madera et al. 2019). Other industry practices exacerbate the issue further: for example, the Ontario Human Rights Commission singled out dress code practices in the province’s restaurant and bar industry, wherein many women employees were encouraged to wear sexualized clothing while at work (Ontario Human Rights Commission n.d.(b)). Such dress codes have the potential to normalize the sexual objectification of women, and make such objectification seem acceptable in certain establishments.

Notably, while women have historically been overrepresented in sales and service occupations, recent data from the Labour Force Survey show that men now make up a large proportion of those employed in these jobs (45%; see Text box 3 table). Despite this change, some observers note that this occupation type is largely devalued in the modern economy, with low wages, weak worker protections and instability (Madera et al. 2019)—in other words, characteristics historically associated with women’s work, and arguably part of its legacy.

Women in healthcare occupations experience high rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviours perpetrated by patients and clients

Similar to sales and service occupations, women have historically been concentrated in jobs related to healthcare—for instance, nursing and personal support—where they also come into frequent contact with patients and members of the public (Robbins et al. 1997). A large proportion of women working in health-related occupations (30%) experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours in the preceding year, and almost two-thirds (63%) of them identified a patient or client as the perpetrator in at least one instance (Chart 3). Said otherwise, among all women working in healthcare occupations, almost one in five (18%) experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour by a patient or client in the previous year.

As with data on sales and service occupations, the genders of the specific clients or patients responsible for the inappropriate sexualized behaviours experienced by women in health occupations is unknown. However, 46% of women in health occupations who had been targeted said that the perpetrator in all instances was a man—a proportion that was not statistically different from women workers overall (56%; data not shown).

Men in healthcare jobs also experienced a high rate of inappropriate sexualized behaviours (19%E), compared to men in many other occupations—although the prevalence of these behaviours among men working in health occupations remained lower than among their colleagues who were women (30%; Chart 2).Note

Women in occupations dominated by men experience higher rates of gender-based discrimination

Discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation more often targeted women working in occupations historically dominated by men. Among women working in the five occupations groups in which men formed the majority, 15% had experienced this form of discrimination; this compared to 9% of women working in job types where most workers were women (data not shown). Specifically, about one in five (21%) women who worked in the trades, transportation, equipment operation and related occupations reported being the target of discrimination; the same was true for 18% of those employed in natural and applied sciences and related occupations (data not shown).

Gender-based workplace discrimination was experienced by 7% of women working in health occupations and 12% of those in sales and service —both occupations in which women historically outnumber men. Just under half (48%E) of women working in sales and service occupations who had experienced discrimination said that a client or customer was involved in at least one incident (data not shown).Note

When it came to gender-based discrimination targeting men, no statistically significant differences were found between occupations in which men or women formed the majority of workers.

Women more often targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours when co-workers are mostly men

While a significant proportion of workers—particularly women and those in sales and service occupations—experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours perpetrated by clients, overall it was co-workers who were most often responsible for inappropriate sexualized behaviour at work. When it came to unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations, for example, 63% of women and 82% of men indicated that at least once, the perpetrator was a co-worker. Similarly, 69% of women and 84% of men who experienced inappropriate communication stated that a co-worker was responsible for at least one incident (Table 3).

While the gendered makeup of many occupation groups can have large-scale influence on how individuals experience inappropriate sexualized behaviour, the gender composition of a worker’s immediate colleagues can also play a role―especially for women workers. For instance, women whose co-workers were mostly men were more likely to experience inappropriate sexualized behaviours than those who worked mostly with women (32% versus 24%). For men, these proportions were relatively equal (18% of those who worked with mostly men and 19% for those who worked with mostly women, a difference not found to be statistically significant; see Table 9).

When it came to gender-based discrimination, both women and men who worked predominantly with members of the other gender were more likely to be targeted. One in five (20%) women who worked with mostly men experienced gender-based discrimination, compared to 7% of those who worked with mostly women. Conversely, 5% of men in work environments dominated by men had this experience, compared to 11% of those who worked with mostly women (see Table 9).

Many of these findings echo those from previous Canadian studies, which examined inappropriate sexualized behaviour in other organized social contexts. For instance, the 2019 Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population found that among postsecondary students, most instances of unwanted sexualized behaviours were perpetrated by peers―specifically, by fellow students who were men (Burczycka 2020). Similarly, while members of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) were not included in the 2020 SSMW, a 2018 study of sexual misconduct in the CAF yielded comparable results (see Text box 4).

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Sexual misconduct in the

Canadian Armed Forces

Workplace sexual misconduct gained high visibility in Canada in 2015, with the publication of retired Supreme Court Justice Marie Deschamps’ external review of sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) (Deschamps 2015). The report, which documented sexual assault, misconduct and discrimination in the military workplace, led to numerous subsequent reports, audits and investigations dedicated to addressing this issue (for instance, see Burczycka 2019; Cotter 2019).

These efforts included the Survey of Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces (SSMCAF). Results from the second (2018) SSMCAF showed that sexual misconduct―which the survey defined in much the same way as the 2020 Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work (SSMW)―persists in the CAF at problematic levels. The SSMCAF found that 28% of women and 13% of men in the Regular Force had been personally targeted with sexualized behaviours or discrimination based on gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in 2018; additionally, 4.3% of women and 1.1% of men had been sexually assaulted (Cotter 2019). Many differences between military and civilian workplaces make comparisons difficult―for instance, the majority of CAF members are men. Nevertheless, these results echo those from the 2020 SSMW, which found that 28% of women and 18% of men in the civilian workforce had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours or gender-based discrimination at work in the previous year, and 1.8% of women and 1.1% of men had been sexually assaulted.

Other aspects of workplace sexual misconduct were similar for both CAF members and those in non-military workplaces. For example, in both groups, those who had been targeted often said that the persons responsible had been peers, as opposed to supervisors or those above them in the chain of command. Additionally, both the SSMCAF and the SSMW found that people―especially women―who had been targeted experienced negative personal and professional consequences as well as anxieties and confusion about how to report their experiences.

End of text box 4

More than one in five workers targeted say someone with authority perpetrated sexualized behaviour

When inappropriate sexualized behaviours in the workplace are perpetrated by someone in authority, the consequences can be especially problematic. Those targeted may feel that their job will be at risk if they speak out, while others may perceive that such behaviours are acceptable in their workplace (Berdahl and Raver 2011; Hershcovis et al. 2021). Data from the 2020 SSMW show that in Canadian workplaces, many women and men were targeted by someone in a position of authority over them, such as a supervisor or boss. Among workers who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours, these proportions ranged from 22% to 28%E among women and 21% to 30% among men, depending on the type of behaviour—differences not found to be statistically significant (Table 3).

Notably, men were more likely than women to have been targeted by a subordinate when it came to both unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations (13%, versus 4% among women) and inappropriate communication (9% versus 6%).

Among both women and men who experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours, someone in a position of equal power in the workplace—at least, in a position of equal formalized power, as opposed to a supervisor or subordinate―was most often responsible. This was true across all categories of behaviours: depending on the type of behaviour, proportions ranged from 45% to 65%E of women who experienced these behaviours, and from 62% to 74%E of men.

With respect to discrimination based on actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that targeted women, 44% said that someone in a position of authority was responsible for at least one incident (Table 4). The proportion among men was similar (36%).

Inappropriate sexualized behaviour, discrimination in the workplace often happen with bystanders present

In addition to the relationships between those targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours and those responsible, the number of people involved—as perpetrators or as witnesses—can speak to the broader workplace culture in which workers spend their days. People who work in a place where multiple individuals take part in inappropriate sexualized behaviour may perceive an unspoken acceptance of these behaviours among colleagues and potentially, management; their experience may differ from those of people who are targeted with sexualized behaviour by one co-worker behind closed doors. These contexts can reflect different workplace cultures and the contrasting ways in which women and men may experience them (Hershcovis et al. 2021).

Many workers who experienced sexualized behaviours in the workplace said that two or more people had been responsible for what happened. Men often indicated that multiple people had perpetrated the behaviour; for example, four in ten (39%) men who had experienced inappropriate communication said that multiple people were always involved, and similar proportions who experienced explicit materials said that it had always involved either one (48%E) or multiple (36%E) perpetrators (a difference not found to be statistically significant). Though many women also experienced behaviours perpetrated by multiple people, more said that it was always one person responsible: this was the case for 71% of women who had experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations, for example (Table 3).Note

Whether or not inappropriate sexualized behaviours happened in the presence of witnesses also speaks to workplace culture: for example, those who participate in inappropriate behaviours with witnesses present may do so because they feel that they will not be penalized. Women and men who experienced these behaviours in the workplace said that bystanders were often present at the time. Among women, much larger proportions of those who experienced inappropriate communication or physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that others were always or sometimes around (73% and 70%, respectively), compared to those who said that no one else was ever present (22% and 24%). Proportions were similar among men.

The presence of bystanders when incidents of discrimination took place followed a similar pattern to inappropriate sexualized behaviours. Among women, two thirds (66%) stated that other people were always or sometimes present when discrimination occurred; this was similar to what was experienced by men (71%) (Table 4).

A minority of women say that bystanders stepped in to stop inappropriate sexualized behaviours

In some cases, those targeted by sexualized behaviours reported that people who had witnessed the incident took action to help stop what was going on. Notably, women were generally more likely than men to say that bystanders had intervened: 31% of women targeted with inappropriate communication in the presence of bystanders said that bystanders had taken action to stop the behaviour, compared to 19% of men. This was also the case for 27% of women and 10%E of men who had experienced inappropriate physical contact and suggested sexual relations in the presence of others (Table 3).

When asked whether those present took any action in response to acts of gender-based discrimination, similar proportions of women (35%) and men (23%E) who were targeted said that they had (a difference not found to be statistically significant; Table 4).

No statistically significant differences were found across occupation types when it came to whether bystanders were present when inappropriate sexualized behaviours happened. However, some differences were noted in the degree to which bystanders took action to stop the behaviour. Workers in health-related occupations were more likely to say that someone had stepped in to intervene when they had experienced sexualized behaviours in the presence of others (39%), compared to workers in business, finance and administration occupations (22%), in natural and applied sciences occupations (20%E), and in trades, transportation and equipment operations and related occupations (20%E, data not shown). While these patterns may suggest differences in workplace culture among these occupation types, they may also be related to who was responsible for the behaviours: for instance, workers in health occupations often experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviours perpetrated by clients or patients, and some individuals may be more inclined to step in when they see a colleague being mistreated by a member of the public than by another co-worker.

Most workers choose not to speak about their experiences with others at work

As all workplaces in Canada must comply with anti-harassment and discrimination laws set out in federal, provincial and territorial legislation, most employers have policies in place to address inappropriate sexualized behaviours in their workplaces—including processes to facilitate reporting and disclosure by those targeted. However, not all workers received this information from their employer: 32% of women and 26% of men said that they had not received any information on how to report sexual harassment and sexual assault, and 34% of women and 28% of men said that they had not been instructed on how to access resources to deal with these situations confidentially (see Table 7).

In line with this, less than half of all workers who experienced these behaviours said that they had discussed the matter with someone at work. Among women, this proportion ranged from 34%E to 52%, depending on the type of inappropriate sexualized behaviour. Among men, it ranged from 20% to 33% (Table 5). Most often, women were more likely than men to say that they had spoken to someone at work about what happened. When it came to discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation, 48% of women and 35% of men reported having discussed what happened with someone at work (a difference not found to be statistically significant; Table 6).

Few workers speak to human resources, union representatives or others tasked with employee welfare

Of those workers who did speak to someone at work about their experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviour, relatively few spoke to human resources, their union, corporate security or someone else responsible for employee welfare. For example, few women who experienced inappropriate communication in the workplace spoke to a human resources advisor or corporate security officer (6% of those who had spoken to someone at work), a union representative (3%), or an ombudsperson or someone responsible for the welfare of employees (1%; Table 5).Note Considerably more had reached out to a person in authority, such as a supervisor, boss or senior manager, including 46% of women who spoke to someone about inappropriate communication and 41% of women who spoke to someone about physical contact or suggested sexual relations. Among men, 39%E of those who had discussed inappropriate communication with someone at work spoke to someone in authority.Note

Similarly, a small proportion of women who had spoken to someone at work about discrimination that they had experienced said that they had contacted a human resources advisor or corporate security officer (7%) or a union representative (6%) (Table 6). About half (50%) said that they had spoken to a supervisor, boss or senior manager about the situation.

Instead, most workers who reached out to another individual in their workplace to discuss their experiences spoke to a colleague or co-worker who had no authority. This included 72% of women who had spoken about inappropriate communication and 74% of women who had spoken about unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations, and 67% of those who spoke about discrimination. Among men, 46%E of those who spoke to someone about inappropriate communication spoke to a co-worker other than a person in authority or a subordinate (Table 5; Table 6).

Workers in some occupation groups were more likely to speak to someone at work about inappropriate sexualized behaviours. For instance, 58% of women in health occupations and 57% of women in sales and service who had been targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour said that they had spoken to someone at work about it; in contrast, this was the case for a lower proportion (39%) of women in business, finance and administration occupations (data not shown). Survey data cannot reveal the relationship between an employee and the perpetrator of a given incident that was or was not brought to someone else’s attention. However, a large proportion of women working in health and service occupations were targeted by a customer or patient, while women in business, finance and administration were often targeted by a co-worker; it is possible that for some, discussing the issue with others can be more or less difficult depending on whether the perpetrator was a member of the public or another colleague.Note

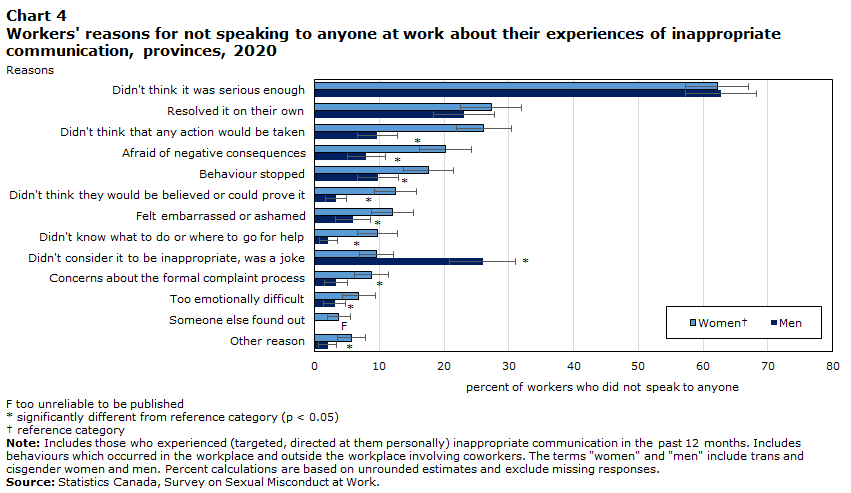

Women say anxieties and mistrust related to reporting keep them from speaking out

The reasons workers gave for not discussing their experiences point to anxieties about the reporting process and the consequences of speaking out—reasons given by women, in particular. Many women who had been targeted with inappropriate communicationNote and chose not to speak to anyone at work about it said that they believed no action would be taken if they spoke out (26%, versus 10% of men); they also feared negative consequences such as retaliation and career implications (20% versus 8%). Some women also stated that they did not think they would be believed or could prove what happened (12% versus 3%) or that they felt embarrassed or ashamed (12% versus 6%). Notably, about a quarter (26%) of men who did not report inappropriate communication said it was because that they did not consider the behaviour to be inappropriate, compared to 10% of women (Chart 4).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Reasons | WomenData table for chart 4 Note † | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of workers who did not speak to anyone | standard error | percent of workers who did not speak to anyone | standard error | |

| Didn't think it was serious enough | 62 | 4.8 | 63 | 5.5 |

| Resolved it on their own | 27 | 4.7 | 23 | 4.7 |

| Didn't think that any action would be taken | 26 | 4.2 | 10Note * | 3.0 |

| Afraid of negative consequences | 20 | 4.0 | 8Note * | 3.0 |

| Behaviour stopped | 18 | 3.9 | 10Note * | 3.2 |

| Didn't think they would be believed or could prove it | 12 | 3.2 | 3Note * | 1.6 |

| Felt embarrassed or ashamed | 12 | 3.2 | 6Note * | 2.6 |

| Didn't know what to do or where to go for help | 10 | 3.1 | 2Note * | 1.5 |

| Didn't consider it to be inappropriate, was a joke | 10 | 2.6 | 26Note * | 5.1 |

| Concerns about the formal complaint process | 9 | 2.6 | 3Note * | 1.8 |

| Too emotionally difficult | 7 | 2.5 | 3Note * | 1.7 |

| Someone else found out | 4 | 1.7 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Other reason | 6 | 2.2 | 2Note * | 1.4 |

F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||

Chart 4 end

Most often, workers who chose not to speak to anyone at work about inappropriate sexualized or discriminatory behaviour said that they did not think the incident was serious enough to report. Depending on the type of behaviour they experienced, between 56% and 62% of women who did not speak to anyone gave this as the reason, along with between 55%E and 63% of men.

Among workers who had experienced discrimination and chose not to speak to anyone at work about it, few differences were noted in the reasons given by women and men. Both women and men often said that they were afraid of negative consequences (26% and 22%), that they didn’t think they would be believed or could prove what happened (16% and 13%), and that they felt embarrassed and ashamed (16% and 13%); none of these differences were found to be statistically significant (Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Reasons | Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of workers who did not speak to anyone | standard error | percent of workers who did not speak to anyone | standard error | |

| Didn't think it was serious enough | 56 | 7.2 | 55 | 13.5 |

| Didn't think that any action would be taken | 39 | 7.7 | 27 | 10.3 |

| Resolved it on their own | 27 | 7.2 | 32 | 13.9 |

| Afraid of negative consequences | 26 | 6.3 | 22 | 9.3 |

| Didn't think they would be believed or could prove it | 16 | 5.3 | 13 | 7.4 |

| Felt embarrassed or ashamed | 16 | 5.4 | 13 | 7.4 |

| Didn't know what to do or where to go for help | 13 | 4.9 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Concerns about the formal complaint process | 13 | 4.8 | 11 | 7.0 |

| Behaviour stopped | 12 | 5.1 | 10 | 6.4 |

| Too emotionally difficult | 11 | 4.2 | 13 | 7.3 |

| Someone else found out | 6 | 4.0 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Didn't consider it to be inappropriate, was a joke | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Other reason | 5 | 3.3 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

|

F too unreliable to be published Note: Differences between women and men are not statistically significant. Includes those who experienced (targeted, directed at them personally) discriminatory behaviours in the past 12 months. Includes behaviours which occurred in the workplace and outside the workplace involving coworkers. The terms "women" and "men" include trans and cisgender women and men. Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and exclude missing responses. Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||

Chart 5 end

Women experience negative professional consequences of inappropriate sexualized behaviours

Inappropriate sexualized and discriminatory behaviours can have many negative consequences for those who experience them. When people are targeted in their workplace, these impacts can be particularly significant. For many people, work is a major source of personal fulfillment, identity and social interaction; it is also a place where many people spend a considerable portion of their time (Walsh and Gordon 2008). When this environment becomes the site of inappropriate sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, the personal and emotional impacts on workers can be significant.

Many workers who were targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviours in the previous year indicated that they had experienced a range of negative impacts as a result. These impacts were especially strong among women: larger proportions of women reported negative consequences, across most impacts where comparisons were possible. Some particularly large gaps between men and women were noted for specific types of impacts. For instance, women who were targeted with sexually explicit material in the workplace were four times more likely to have avoided optional work-related social functions as a result (34%E, versus 8%E among men; Table 5). Similarly, women who experienced inappropriate communication at work were three times more likely than men to have avoided or wanted to avoid specific locations or tasks at work (30% versus 10%) and to have wanted to miss work or work fewer hours (17% versus 6%). Notably, women were almost four times as likely as men to seek out support services for help dealing with inappropriate communication in the workplace (7% versus 2%).

Impacts of unwanted physical contact, suggested sexual relations similar for women and men

In terms of impacts, the gap between women and men was smallest when it came to unwanted physical contact and suggested sexual relations. Although women who experienced this were still more likely to report avoiding or wanting to avoid both specific people at work (60%, versus 44% among men) and specific locations or tasks (38% versus 28%), other impacts were as common for men as for women. This included losing trust in authority at work or in the organization itself (20% of men and 26% of women), avoiding optional work-related social functions (18% and 22%), having difficulty doing their work (17% and 23%) and wanting to change jobs, transfer or quit (16% and 25%)―none of which were statistically significant differences. This suggests that relative to the other behaviours measured by the survey, unwanted physical contact and suggested sexual relations in the workplace have an especially negative effect on men.

Similar to unwanted physical contact and suggested sexual relations, relatively small gaps in terms of consequences were noted between women and men who had experienced discrimination in the workplace. For example, similar proportions of women and men said that the experience had made them want to change jobs, transfer or quit (34% of women and 28% of men), had caused them to avoid or want to avoid specific locations or tasks at work (31% and 29%), or had resulted in difficulties doing their work (27% and 26%). A sizable proportion of both women and men stated that their experiences of discrimination had caused a negative emotional impact (42% and 39%; Table 6).Note

A notable consequence of inappropriate communication in the workplace which was as common among men as it was among women was the use of drugs or alcohol to cope with the experience. This impact was reported by 5% of women and 6% of men who had experienced inappropriate communication, a difference not found to be statistically significant (Table 5). Previous research has suggested that the link between substance use and psychological distress is particularly strong among men (Burczycka 2018).

Most workers see their workplace as fair when it comes to gender, sexual orientation of workers

Workplace culture is difficult to quantify, and observers look to many different aspects of work life in their attempts at measurement (Stainback 2011). When it comes to inappropriate sexualized behaviours and gender-based discrimination, factors such as those measured by the SSMW appear relevant. The widespread nature of these behaviours, the fact that many happen in a group setting, the involvement of those with authority in a significant number of incidents, and the anxiety that many workers—especially women—have about speaking out suggest that tacit acceptance of inappropriate sexualized behaviours and gender-based discrimination permeates the culture of many Canadian workplaces.

In addition to these factors, the SSMW asked workers about how they think workers of different genders—men, women and transgender peopleNote —are treated at their workplace. Overall, most workers felt that everyone at their workplace is treated fairly regardless of gender. For example, eight in ten (82%) women and nine in ten (87%) men agreed or strongly agreed that at their workplace, every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of their gender or assumed gender (Table 7). At the same time, one in ten women (10%) and 4% of men stated that they had personally experienced gender-based discrimination in their workplace (Table 2).Note

Similarly, most workers―83% of women and 86% of men―agreed or strongly agreed that their workplace treats workers fairly regardless of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation (Table 7). This kind of workplace discrimination, meanwhile, was reported by 7% of LGBTQ2Note women and 12% of LGBTQ2 men (a difference not found to be statistically significant). Notably, 27% of LGBTQ2 women had experienced discrimination based on gender or perceived gender at work in the previous year—a proportion almost three times larger than among LGBTQ2 men (10%; data not shown).

Overall, fewer LGBTQ2 workers agreed or strongly agreed that at their work, every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation (78%, versus 86% of non-LGBTQ2 workers) or whether or not they are, or are assumed to be, transgender (69% versus 79%; Chart 6). Notably, these differences reflected answers given by men: among women, no statistically significant differences were found between women who identified as LGBTQ2 and those who did not.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Workers' perceptions of peoples' experiences | LGBTQ2 womenData table for chart 6 Note † | Non-LGBTQ2 women | LGBTQ2 menData table for chart 6 Note † | Non-LGBTQ2 men | Total LGBTQ2 workersData table for chart 6 Note † | Total non-LGBTQ2 workers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | percent who agree or strongly agree | standard error | |

| Every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation | 81 | 6.0 | 84 | 1.6 | 76 | 8.2 | 88Note * | 1.5 | 78 | 5.1 | 86Note * | 1.1 |

| Every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of whether or not they are, or are assumed to be, transgender | 70 | 7.1 | 77 | 1.8 | 67 | 8.5 | 80Note * | 1.8 | 69 | 5.6 | 79Note * | 1.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Sexual Misconduct at Work. |

||||||||||||

Chart 6 end

Those with personal experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviour, discrimination less likely to see workplace as fair

When it came to the women and men in general, those who had personally experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour or discrimination at work were less inclined to see their workplace as fair and free of harmful stereotypes—for example, if men are expected to avoid taking parental leave, or if women are expected to wear revealing clothing. For instance, women who had been targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour were more likely than those who had not to say that there are sexist or gender specific stereotypes that have an impact on women's experience at work (42% versus 22%; data not shown). Results were similar among men: for example, a smaller proportion of those who had been targeted felt that at their work, every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of their gender or assumed gender, compared with men who had not been targeted (78% versus 89%). For both women and men, this pattern was consistent for every question measuring workers’ perceptions of their workplace.Note

The gap between workers who saw their workplace as fair and free of stereotypes and those who were more critical was widest when it came to experiences of gender-based discrimination. For example, among women, those who had experienced this type of discrimination were less likely to see their work as a place where every person has equal advancement opportunities regardless of their gender or assumed gender (55%), compared to those who had not experienced discrimination (85%). Similarly, among men, those who had been discriminated against were more than twice as likely to feel that there are sexist or gender specific stereotypes that have an impact on men's experience at work, compared to those who had not experienced discrimination (60% versus 27%).

Inappropriate sexualized behaviour and gender-based discrimination at work among marginalized populations

Inappropriate sexualized behaviour, gender-based discrimination and sexual assault common among young workers, workers with disabilities

In Canada, certain populations are more at risk of experiencing multiple types of victimization. Women, young people, Indigenous peoples, people with a disability and LGBTQ2 people are consistently overrepresented as victims of violence and other types of criminal and non-criminal victimization (Conroy and Cotter 2017; Cotter 2018; Jaffray 2020). Findings from the SSMW also suggest that certain populations may be more at risk of inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation that occur in the workplace. Notably, some of these groups face other barriers to equality in employment and economic participation (Banerjee 2008; Hira-Friesen 2018; Schur 2009), representing additional vulnerabilities to maltreatment and exploitation.Note

As noted throughout the present article, inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination target women in the workplace in greater proportions than men. Among women, those younger than 35 were especially overrepresented: 39% of women aged 15 to 24 and 36% of those aged 25 to 34 experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour, proportions which decreased with age. This was also the case among women who experienced discrimination, with 18% of those aged 15 to 24 and 14% of those aged 25 to 34 reporting having been targeted. A similar pattern was noted among men, and among women who had experienced sexual assault related to their workplace (Table 8). These findings echo other Canadian population studies, which have consistently found that young people experience higher rates of victimization and misconduct (Conroy and Cotter 2017; Conroy 2018).

Individuals with a disability face particular challenges when it comes to participation in the workforce, many of which have been well-documented (Schur 2009). Additionally, people with disabilities—especially women—are at higher risk of sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in general (Cotter 2018; Cotter and Savage 2019). In the workplace, women with a disability were more likely to have experienced both inappropriate sexualized behaviours (35%) and gender-based discrimination (16%) than women without a disability (20% and 7%, respectively); they were also more likely to have been sexually assaulted in a workplace setting (3% versus 1%). Men with a disability were also at higher risk: 25% had been targeted with inappropriate sexualized behaviour, 10% with discrimination, and 3% had been sexually assaulted. Proportions were considerably lower among men who did not have a disability (15%, 4% and 1%, respectively).

Gay and bisexual workers experience higher rates of inappropriate sexualized behaviour, discrimination than heterosexual workers

As in other public and private spaces, people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or have another sexual orientation besides heterosexual experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour in the workplace more often than their heterosexual colleagues. This was the case for bisexual women in particular, among whom six in ten (59%) reported being targeted—well over twice the proportion as among heterosexual women (24%; Table 8). Similarly, gay men were twice as likely as heterosexual men to have been targeted by inappropriate sexualized behaviour in a work-related setting (32%E versus 16%). Discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation also affected this group disproportionately: 30% of bisexual women experienced discrimination, compared to 9% of heterosexual women, while gay men were four times as likely as heterosexual men to have been targeted (16%E versus 4%).

People whose gender is different than the sex to which they were assigned at birth, those with no gender, multiple genders or with an identity outside the gender binary face higher rates of discrimination, victimization and targeted misconduct in many spheres of public and private life (Jaffray 2020). Analysis of their experiences with inappropriate sexualized behaviours and discrimination in the workplace was not possible here, due to data limitations; however, their responses were combined with those given by people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or have another sexual orientation besides heterosexual (collectively referred to here as LGBTQ2). LGBTQ2 workers were considerably more likely to have experienced each of the sexualized and discriminatory behaviours at work for which comparisons were possible, compared to their non-LGBTQ2 colleagues: overall, almost half (47%) of LGBTQ2 workers were targeted (compared to 22% of non-LGBTQ2 workers; data not shown). For most behaviours, LGBTQ2 workers were two, three or four times more likely to have been targeted.