Labour Force Survey, August 2021

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2021-09-10

August Labour Force Survey (LFS) data reflect labour market conditions during the week of August 15 to 21.

By the August reference week, most jurisdictions in Canada had implemented the final or near-final stages of their public health reopening plans. Indoor locations, such as restaurants, recreation facilities, personal care services, retail stores, and entertainment venues, were generally permitted to be open, with varying degrees of capacity restrictions. In addition, for the first time since March 2020, on August 9 fully vaccinated non-essential travellers from the United States were permitted to enter Canada without quarantine requirements, expanding potential clientele for businesses in tourist areas.

Highlights

Employment rises for third consecutive month

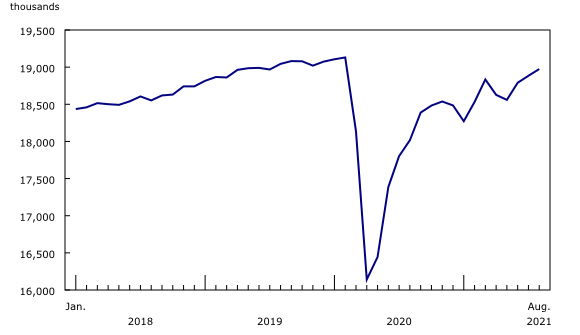

Employment rose by 90,000 (+0.5%) in August, the third consecutive monthly increase. Employment is within 156,000 (-0.8%) of its February 2020 level, the closest since the onset of the pandemic.

August employment gains were concentrated in full-time work (+69,000; +0.4%).

Increases were mainly in services-producing industries, led by accommodation and food services, and were spread across multiple demographic groups.

Total hours worked were little changed and were 2.6% below their pre-pandemic level.

Most of the employment gains occurred among private sector employees (+77,000; +0.6%).

Self-employment was little changed.

Among workers who worked at least half their usual hours, the proportion working from home fell 1.8 percentage points to 24.0% in August, the lowest share since the onset of the pandemic.

Employment increased in the services-producing sector for the third consecutive month in August (+93,000), led by gains in accommodation and food services (+75,000), and information, culture and recreation (+24,000).

The number of people working in construction increased (+20,000; +1.4%) for the first time since March 2021.

Employment increased in Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. All other provinces recorded little or no change.

Unemployment rate at lowest level since February 2020

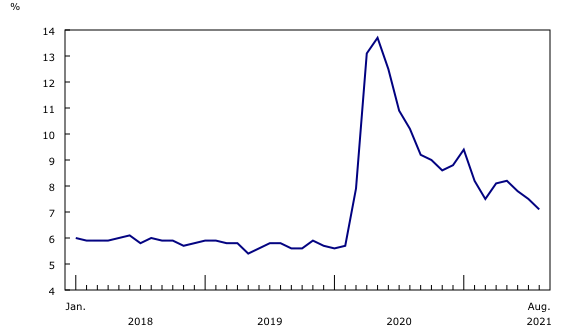

The unemployment rate fell 0.4 percentage points to 7.1% in August, the lowest rate since the onset of the pandemic.

The unemployment rate among 15-to-69-year-olds who belong to population groups designated as visible minorities was 9.8% in August, little changed for a second consecutive month.

Long-term unemployment dropped 29,000 (-6.7%) to 394,000 in August, but remained 215,000 (+120.0%) higher than in February 2020.

Employment rises for third consecutive month

Employment rose by 90,000 (+0.5%) in August, the third consecutive monthly increase. The unemployment rate fell 0.4 percentage points to 7.1%.

Employment gains were concentrated in full-time work (+69,000; +0.4%). Increases were mainly seen in services-producing industries, led by accommodation and food services, and were spread across multiple demographic groups.

Combined with gains in June and July, the August increase brought employment to within 156,000 (-0.8%) of its February 2020 level, the closest since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The employment rate was 60.5% in August, 1.3 percentage points below the pre-pandemic rate.

The number of employed people who worked less than half their usual hours was little changed in August, however, and remained elevated compared with February 2020 (+29.9%). Total hours worked were also little changed and were 2.6% below their pre-pandemic level.

Self-employment continues to lag

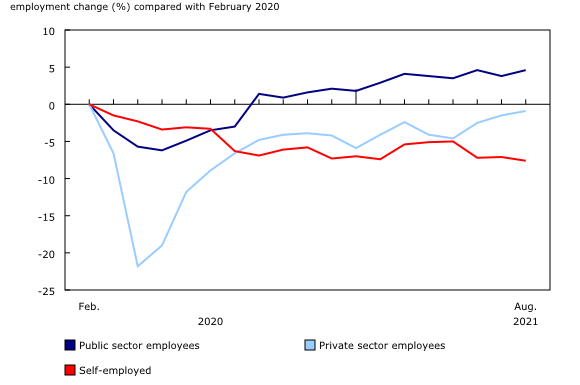

Most of the employment gains in August occurred among private sector employees (+77,000; +0.6%), bringing their number to within 0.9% (-114,000) of its February 2020 level. Following a small dip in July, the number of employees in the public sector rebounded to its June level, rising 30,000 (+0.7%), and was up 180,000 (+4.6%) compared with February 2020.

In contrast, self-employment was little changed in the month, remaining 7.7% (-222,000) below its pre-pandemic level. August marks the fifth consecutive month with no growth in self-employment.

The share of Canadians working from home continues to fall

Among workers who worked at least half their usual hours, the proportion working from home fell 1.8 percentage points to 24.0% in August, the lowest share since the onset of the pandemic. Just under half of those working from home (47.3%) reported that their usual work location was outside their home, down from two-thirds (66.8%) during the initial widespread lockdown in April 2020.

In addition to employment gains or losses, and changes in work location, the number of people working at different locations may be affected by work absences, which are typically higher during the summer when workers are more likely to be on vacation.

Employment rate among youth returns to pre-pandemic level

Employment among youth aged 15 to 24 rose 22,000 (+0.9%) in August, entirely in part-time work. Although total youth employment was 41,000 (-1.6%) below its pre-pandemic level in August, the youth employment rate (57.6%)—the proportion of the population aged 15 to 24 who are employed—had essentially returned to its February 2020 level, a result of declines in the size of the youth population.

The difference in the labour market outcomes between male and female youth has been notable during much of the pandemic period. Among women aged 15 to 24, employment rose 35,000 (+2.8%) in August. As a result, employment among young women essentially returned to its February 2020 level for the first time. Overall employment among young men dipped slightly below its pre-pandemic level in August (-30,000; -2.3%) after having essentially recovered in July; however, employment rates among both young men (56.0%) and women (56.3%) were on par with pre-pandemic rates.

Notable employment gains since May among teens aged 15 to 19 (+140,000; +17.8%) have led to a widening gap in employment recovery between younger and older youth. Among teenagers, employment in August was 50,000 higher (+5.8%) than in February 2020; whereas employment among youth aged 20 to 24 was 92,000 lower (-5.3%). LFS results in the coming months will shed light on whether this trend continues into the fall, with many youth returning to school.

Summer student employment lags pre-pandemic level among young women

The challenges faced by older youth are also reflected in the labour market outcomes for returning students.

From May to August, the LFS collects labour market data on youth aged 15 to 24 who were attending school full time in March and who intend to return to school in the fall. Published data are not seasonally adjusted, therefore comparisons can only be made on a year-over-year basis.

For returning students aged 15 to 24, the average employment rate for May to August was 50.3%, 2.0 percentage points lower than the average rate for the summer of 2019 (52.3%), while it was nearly 10 percentage points higher than the rate in the summer of 2020 (40.4%).

The average summer employment rate for female students (52.6%) was down 3.6 percentage points from the 2019 summer average (56.2%), mostly due to a notably lower rate in May 2021. In comparison, the rate for male students (47.6%) was little changed from its pre-pandemic level.

Younger returning students fared better than older students in the 2021 summer labour market. The average employment rates for returning students aged 15 to 16 (29.3%) and 17 to 19 (57.0%) were essentially on par with those seen in the summer of 2019; while the rate for students aged 20 to 24 (63.0%) was down 5.1 percentage points. The employment rate among female students aged 20 to 24 was furthest from the 2019 summer average, down 7.5 percentage points to 64.3%.

Employment growth for core-aged men and older workers

Employment for core-aged men (that is, those aged 25 to 54) rose 24,000 (+0.4%) in August, while it was little changed for core-aged women. Among core-aged men, full-time gains (+49,000; +0.8%) more than offset part-time losses (-25,000; -6.1%). Employment for the core-aged population was 84,000 (-0.7%) below its February 2020 level, with similar deficits for men (-47,000) and women (-37,000).

Among Canadians aged 55 and older, employment rose 28,000 (+0.7%) in August. Employment for older women remained 39,000 (-2.1%) lower than in February 2020, while employment for older men had returned to its pre-pandemic level in March 2021.

Employment rate rises for Filipino Canadians

In August, the employment rate increased among Filipino Canadians (+4.6 percentage points to 77.9%). In contrast, the employment rate for Black Canadians was down 3.6 percentage points to 71.8%. Among those who are not members of groups designated as visible minorities and who are not Indigenous, the employment rate (70.8%) was little changed from July (not seasonally adjusted).

Employment rate for very recent immigrants continues upward trend

The employment rate for very recent immigrants (in Canada for five years or less) continued its upward trend in August, reaching 70.4%, or 6.1 percentage points higher than in August 2019 (three-month moving average, not seasonally adjusted).

Among immigrants who have been in Canada for more than five years, the employment rate was 58.5% in August, down 1.5 percentage points compared with August 2019. For people born in Canada, the employment rate was 61.4%, down 2.2 percentage points from its pre-COVID level (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

Among Indigenous people, employment rate recovers for both men and women

In August, the employment rate among both Indigenous men (60.9%) and women (54.7%) was little changed from August 2019. This marks the first month in which the rate was on par with its pre-pandemic level for Indigenous women, while the rate among Indigenous men had recovered by May 2021. Despite this recovery, employment rates for both Indigenous men and women remained lower than those of their non-Indigenous counterparts, consistent with historical trends.

Among non-Indigenous people, the employment rate in August remained lower than two years ago for both men (65.8%; -1.7 percentage points) and women (56.7%; -1.6 percentage points) (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

LFS information for Indigenous people reflects the experience of those who identify as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, and who live off reserve in the provinces.

Unemployment rate at lowest level since February 2020

The unemployment rate fell for the third consecutive month in August, down 0.4 percentage points to 7.1%, the lowest rate since the onset of the pandemic. The unemployment rate peaked at 13.7% in May 2020 and has trended downward since, despite some short-term increases during the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021. In the months leading up to the pandemic, the unemployment rate had hovered around historic lows and was 5.7% in February 2020.

The adjusted unemployment rate—which includes those who wanted a job but did not look for one—was 9.1% in August, down 0.4 percentage points from one month earlier.

Drop in unemployment led by core-age men and women aged 55 and older

Unemployment among core-aged men fell by 43,000 (-9.3%) in August. The unemployment rate for this group was down 0.6 percentage points to 6.2%, but remained 1.4 percentage points higher than its pre-pandemic level of 4.8%.

For core-age women, unemployment was virtually unchanged in August and their unemployment rate was 5.8%, 1.1 percentage points above the pre-pandemic level.

Among people aged 55 and older, unemployment fell by 26,000 (-7.3%) in August, almost entirely among older women. The unemployment rate for older women (6.8%) was 1.8 percentage points higher than in February 2020, while for men (7.7%) it was 2.4 percentage points higher.

Unemployment for youth aged 15 to 24 was little changed in August. The unemployment rate for male youth (13.2%) was 1.4 percentage points higher than in February 2020, while the rate for female youth (9.8%) was virtually the same as its pre-pandemic level.

Unemployment rate little changed for most visible minority groups

The unemployment rate among 15-to-69-year-olds who belong to population groups designated as visible minorities was 9.8% in August, little changed for a second consecutive month (not seasonally adjusted). Chinese Canadians were the sole visible minority group to see a change in their unemployment rate (down 2.3 percentage points to 9.5%; not seasonally adjusted).

In contrast, the unemployment rate rose for a second consecutive month among people who were not Indigenous or a visible minority, up 0.5 percentage points to 7.0% (not seasonally adjusted).

Number of long-term unemployed declines in August but remains a large proportion of the unemployed

Long-term unemployment—the number of people continuously unemployed for 27 weeks or more—dropped 29,000 (-6.7%) to 394,000 in August, but remained 215,000 (+120.0%) higher than in February 2020. The long-term unemployed accounted for 27.4% of all unemployed in August, up from 15.6% just before the onset of the pandemic.

Compared with its pre-COVID-19 level, long-term unemployment was up for all age groups in August, including youth aged 15 to 24 (+55.0%); core-aged people aged 25 to 54 (+128.1%); and people aged 55 and older (+143.1%). Among youth and core-aged people, the increase was larger for men than for women, while among older workers the increase was greater for women than it was for men.

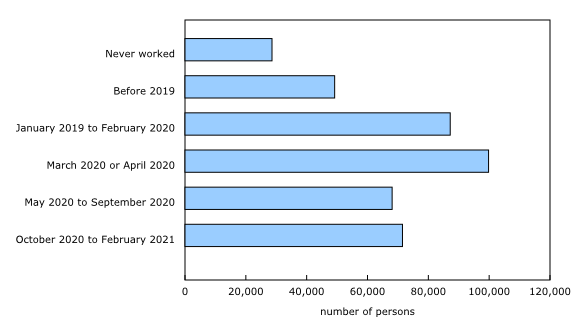

Among those who had been continuously unemployed for 27 weeks or more in August, one-third (33.7%; 136,000, not seasonally adjusted) had last worked prior to March 2020, and an additional 7.1% (29,000; not seasonally adjusted) had never worked. The remaining 59.2% of the long-term unemployed had lost or left their last job at some point during the pandemic. This includes 24.7% (100,000; not seasonally adjusted) who had last worked in March or April 2020, when the initial COVID-19 economic shutdown resulted in unprecedented employment losses, and 34.5% (140,000; not seasonally adjusted) whose last job ended between May 2020 and February 2021.

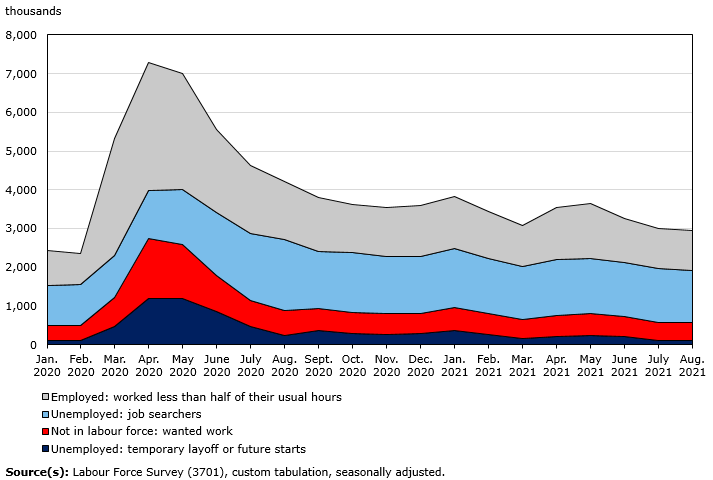

Labour market underutilization holds steady

The labour underutilization rate was little changed at 14.2% in August. Above and beyond the unemployment rate, this rate reflects the proportion of people in the potential labour force who are unemployed; want a job but have not looked for one; or are employed but working less than half of their usual hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19. The number of people searching for work dropped by 81,000 (-5.7%) in August and was the only component of underutilization to decline in the month.

Three of the four components of the underutilization rate remained higher than before the pandemic. Compared with February 2020, there were more job searchers (+288,000; +27.7%); more people who were employed but worked less than half their usual hours (+243,000; +29.9%); and more people who wanted a job but who did not look for one (+68,000; +17.2%). The number of people on temporary layoff was virtually the same as it was pre-pandemic.

Participation in the labour force at pre-pandemic levels for most demographic groups

The labour force participation rate—the total number of people who are employed or unemployed as a proportion of the population aged 15 and older—is an indicator of the balance between the number of people who are working or looking for work, and the number of people who are pursuing other activities, including studying, caring for family members, and pursuing leisure or voluntary activities.

The participation rate fell 0.1 percentage points to 65.1% in August. The rate declined 0.4 percentage points to 91.1% among core-aged men, rose 0.5 percentage points to 65.1% for youth, and was little changed for the other major demographic groups.

In recent months, participation rates have returned to what they were before the pandemic among all demographic groups except for among women aged 55 and older, where the August rate (31.5%) remained 1.0 percentage points below its February 2020 level.

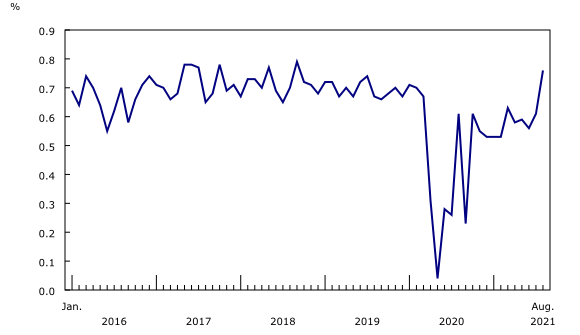

Job-changing rate increases

As the easing of COVID-19 public health restrictions continues, employers face a number of challenges in resuming full business activities. At the same time, workers face their own challenges whether they are returning to their previous industries and occupations, or entering into new fields. During this period of adjustment between labour demand and supply, supplementary measures of labour market churn—the number of people changing employment status or changing jobs—are important complements to concepts such as employment, unemployment and job vacancies.

The number of core-aged job leavers—people who left a job voluntarily in the previous 12 months and remained not employed in the LFS reference week—trended down throughout 2020 and early 2021, reaching a record low of 217,000 in April 2021. Since then, the number of job leavers has increased in parallel with improving labour market conditions. This increase continued in August, when the number of job leavers stood at 275,000, up from 257,000 in July (not seasonally adjusted). Despite this increase, the number of job leavers was substantially lower than in August 2019 (-89,000; -24.4%).

In addition to job leavers, labour market churn includes job changers (workers who remain employed from one month to the next but who change jobs between months). The job-changing rate has gradually increased over the past year after falling to virtually zero in May 2020 following the initial COVID-19 economic shutdown. The job-changing rate was 0.8% in August, up from 0.6% in July. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the job-changing rate averaged 0.7% over the period from 2016 to 2019, and ranged from 0.6% to 0.8%.

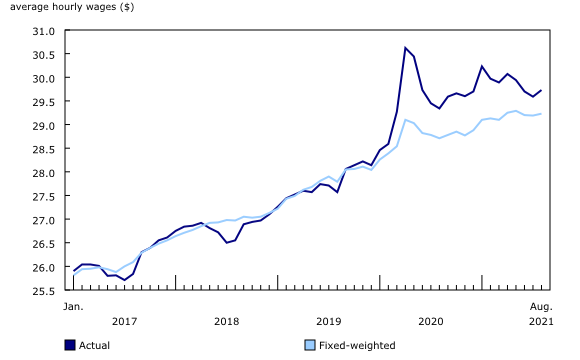

Wage growth continues to be influenced by changes in the composition of employment

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, indicators of wage change have been influenced by the fact that large employment decreases and increases have been proportionately larger among lower-paid workers.

Various methods exist to provide a clearer picture of wage trends by removing the effects of changes in the composition of employment. One such method—a fixed-weighted average wage—holds the distribution of employees across occupations and job tenures constant at the 2019 average.

Based on the fixed-weighted average, average wages were up 5.2% (+$1.48) in August compared with the 2019 average. Without controlling for compositional changes, actual average wages were 7.1% (+$1.98) higher in August 2021 than in 2019 (not seasonally adjusted).

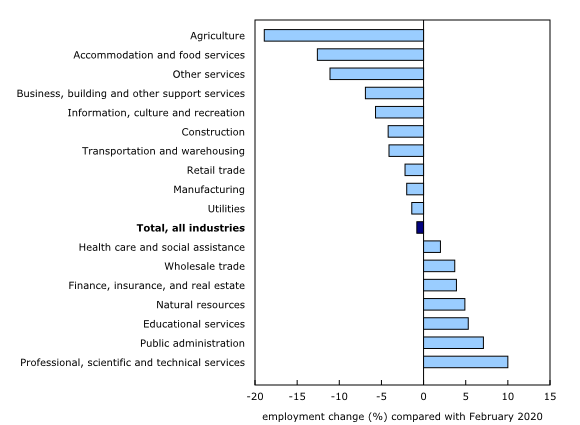

Services-producing sector employment returns to pre-COVID level

Employment increased in the services-producing sector for the third consecutive month in August (+93,000), led by gains in accommodation and food services (+75,000), and information, culture and recreation (+24,000).

Smaller monthly increases were also recorded in professional, scientific and technical services (+15,000), and public administration (+14,000), while employment declined in "other services" (-30,000), finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (-17,000), and business, building and other support services (-17,000).

The overall gain in August pushed employment in the services-producing sector as a whole back to its pre-COVID level for the first time, although not all industries within the sector have fully recovered.

In August, the number of people working in the goods-producing sector was little changed, with gains in construction (+20,000) partially offset by a decline in agriculture (-11,000).

Gap with pre-COVID employment remains uneven across the services-producing sector

Despite the overall return to pre-COVID employment in the services-producing sector in August, several industries remain further behind in their recovery.

In services-producing industries that were deemed essential during the pandemic, or where a high proportion of workers were able to work from home, COVID-related job losses were initially more moderate, and employment is now well above pre-pandemic levels. This includes professional, scientific and technical services (+10.0%; +153,000), public administration (+7.1%; +71,000) and educational services (+5.3%; +73,000).

Employment remains below pre-COVID levels in services-producing industries where a higher proportion of jobs involve close contact with others, with accommodation and food services (-12.6%; -154,000) and "other services" (-11.1%; -90,000) posting notable gaps in August compared with February 2020.

Employment in accommodation and food services at pre-COVID level in two provinces

Employment rose by 75,000 (+7.5%) in accommodation and food services in August, with most of the increase concentrated in Ontario. LFS results for August fully capture the reopening of indoor dining in the province, which occurred towards the end of the July LFS reference week.

While employment in the industry remains behind pre-pandemic levels in most provinces, the number of workers in accommodation and food services has returned to its pre-COVID level in New Brunswick and Manitoba.

More people working in information, culture and recreation

In August, employment increased by 24,000 (+3.4%) in information, culture and recreation, with nearly all of the gains in Ontario. Border restrictions on non-essential travel were lifted for fully vaccinated Americans on August 9 and spectator sports began to welcome back live audiences at the beginning of the month.

While employment in information, culture and recreation remains 5.7% (-44,000) below its pre-pandemic level nationally, the number of people working in the industry has returned to its February 2020 level in five provinces, including Ontario and British Columbia.

Service-sector growth tempered by losses in "other services"

The number of people working in "other services," which includes religious, grant-making, civic and professional organizations, as well as repair and maintenance services, declined by 30,000 (-4.0%) in August, almost entirely as a result of losses in Ontario and British Columbia.

In August, employment also declined in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (-17,000; -1.3%) and business, building and other support services (-17,000; -2.3%).

First employment increase in construction since March 2021

Employment in the goods-producing sector was little changed for the second consecutive month. The sector has yet to recoup losses recorded in May and June 2021, and employment remained 3.6% (-142,000) below its pre-COVID level in August. Most of the remaining gap in the sector is attributable to the construction (43.6%) and agriculture (39.9%) industries.

The number of people working in construction increased for the first time since March 2021, rising by 20,000 (+1.4%). Nearly all of the gains were in Ontario and British Columbia. Despite the monthly increase, the industry remains 4.2% (-62,000) below the level recorded in February 2020.

Employment in agriculture declined by 11,000 (-4.2%) in August. After a partial recovery of COVID-related job losses in late 2020, employment in the industry has declined by 38,000 since November 2020, and was 18.9% (-57,000) below its pre-COVID level in August 2021, proportionally the largest gap among all industries.

Businesses in the agriculture industry have faced a number of challenges since the beginning of the pandemic. Fewer agricultural workers entered Canada through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program in 2020 (Agriculture and agri-food labour statistics, 2020) and, more recently, ongoing drought conditions in Western Canada have negatively affected crop growth and yield potential across much of the Prairies (Production of principal field crops, July 2021).

Employment up in four provinces

Employment increased in Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia in August. All other provinces recorded little or no change. For the third consecutive month, British Columbia was the lone province with employment above its pre-pandemic level. Compared with February 2020, the employment gap was largest in Prince Edward Island (-3.4%) and New Brunswick (-2.7%).

For further information on key province and industry level labour market indicators, see "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app."

Employment in Ontario rose for the third successive month (+53,000; +0.7%) in August, nearly all in part-time work. In the Toronto census metropolitan area, employment increased by 73,000 (+2.1%). The additional employment brought overall provincial gains since May 2021 to 242,000 (+3.4%). The accommodation and food services industry contributed the bulk of the employment increase, while educational services, and information, culture and recreation also had notable gains. In contrast, there were notable declines in manufacturing, and "other services." For the second consecutive month, the unemployment rate in Ontario fell, dropping 0.4 percentage points to 7.6%.

In Alberta, where most public health restrictions were lifted as of July 1, employment rose by 20,000 (+0.9%) in August, the first notable increase since March 2021. Gains were led by transportation and warehousing, followed by information, culture and recreation, and accommodation and food services. The unemployment rate fell 0.6 percentage points to 7.9%, the lowest since the pre-pandemic rate of 7.5% in February 2020.

In Saskatchewan, employment increased by 10,000 (+1.8%) in August, offsetting losses in June and July. Employment was up in wholesale and retail trade, following losses in June and July. The unemployment rate in Saskatchewan held steady at 7.0%.

Employment in Nova Scotia rose by 3,900 (+0.8%) in August, with all of the increase in part-time work. The employment rate rose 0.4 percentage points to 56.6%, but remained lower than in February 2020 (57.5%). The unemployment rate dropped 0.6 percentage points to 7.8%.

Employment rate remains higher in Canada than in the United States

While international comparisons of the pandemic's impact on labour markets are challenging due to differences in concepts, survey design and reference periods, comparisons between the labour market situation in Canada and in the United States can be made by adjusting Canadian data to US concepts. For more information, see "Measuring Employment and Unemployment in Canada and the United States – A comparison."

A frequent point of comparison between Canada and the United States is the employment rate, defined as the number of people who are employed as a percentage of the working-age population, which is typically higher in Canada. Adjusted to US concepts, and for the population aged 16 and older, the employment rate was 61.0% in Canada and 58.5% in the United States in August. The rate was down 1.4 percentage points from February 2020 in Canada, compared with a drop of 2.6 percentage points in the United States.

The unemployment rate, adjusted to US concepts, was 5.8% in Canada in August, 0.6 percentage points higher than in the United States (5.2%). The rate was 1.2 percentage points higher than in February 2020 in Canada, while in the United States it was 1.7 percentage points higher.

The labour force participation rate, also adjusted to US concepts, was 64.7% in Canada in August, down 0.7 percentage points from February 2020. In the United States, the participation rate was 61.7%, a decrease of 1.6 percentage points from February 2020.

Looking ahead

Over the coming months, labour market conditions may be influenced by ongoing developments, including continuing vaccination efforts, rising COVID-19 cases, the start of a new school year, and the lifting of border restrictions for all fully vaccinated international visitors on September 7. LFS results for the week of September 12 to 18 will be released on October 8.

Sustainable Development Goals

On January 1, 2016, the world officially began implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—the United Nations' transformative plan of action that addresses urgent global challenges over the next 15 years. The plan is based on 17 specific sustainable development goals.

The Labour Force Survey is an example of how Statistics Canada supports the reporting on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development. This release will be used in helping to measure the following goals:

Note to readers

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates for August are for the week of August 15 to 21.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey."

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

LFS estimates at the Canada level do not include the territories.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH); Employment Insurance Statistics; and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and those from the SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

Since March 2020, all LFS face-to-face interviews have been replaced by telephone interviews to protect the health of both respondents and interviewers. While this has resulted in a decline in the LFS response rate, more than 40,000 interviews were completed in August and in-depth data quality evaluations conducted each month confirm that the LFS continues to produce an accurate portrait of Canada's labour market.

The suspension of face-to-face interviewing has had a larger impact on response rates in Nunavut than in other jurisdictions. Due to the larger decline in response rates for Nunavut, and resulting changes in the composition of the responding sample, data for Nunavut (table 14-10-0292-01) should be used with caution. To reduce the risks associated with declining data quality for Nunavut, users are advised to use 12-month averages (available upon request) rather than 3-month averages when possible. Statistics Canada will continue to monitor the quality of LFS data for Nunavut each month and provide users with updated guidelines as required.

In addition, all telephone interviews were conducted by interviewers working from their home and none were done from Statistics Canada's call centres.

The distribution of LFS interviews in August 2021 compared with July 2021, was as follows:

Telephone interviews – from interviewer homes

• July 2021: 63.6%

• August 2021: 64.1%

Online interviews

• July 2021: 36.4%

• August 2021: 35.9%

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

The five occupation groups with the lowest average hourly wages in 2019: sales support occupations; service support and other service occupations, n.e.c.; service supervisors and specialized service occupations; labourers in processing, manufacturing and utilities; and service representatives and other customer and personal services occupations.

The five occupation groups with the highest average hourly wages in 2019: professional occupations in natural and applied sciences; occupations in front-line public protection services; middle management occupations in trades, transportation, production and utilities; specialized middle management occupations; senior management occupations.

Total hours worked refers to the number of hours actually worked at the main job by the respondent during the reference week, including paid and unpaid hours. These hours reflect temporary decreases or increases in work hours (for example, hours lost due to illness, vacation, holidays or weather; or more hours worked due to overtime).

In general, month-to-month or year-to-year changes in the number of people employed in an age group reflect the net effect of two factors: (1) the number of people who changed employment status between reference periods, and (2) the number of employed people who entered or left the age group (including through aging, death or migration) between reference periods.

Supplementary indicators used in August 2021 analysis

Employed, worked zero hours includes employees and self-employed who were absent from work all week, but excludes people who have been away for reasons such as 'vacation,' 'maternity,' 'seasonal business,' and 'labour dispute.'

Employed, worked less than half of their usual hours includes both employees and self-employed, where only employees were asked to provide a reason for the absence. This excludes reasons for absence such as 'vacation,' 'labour dispute,' 'maternity,' 'holiday,' and 'weather.' Also excludes those who were away all week.

Not in labour force but wanted work includes persons who were neither employed, nor unemployed during the reference period and wanted work, but did not search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Unemployed, job searchers were without work, but had looked for work in the past four weeks ending with the reference period and were available for work.

Unemployed, temporary layoff or future starts were on temporary layoff due to business conditions, with an expectation of recall, and were available for work; or were without work, but had a job to start within four weeks from the reference period and were available for work (don't need to have looked for work during the four weeks ending with the reference week).

Labour underutilization rate (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) combines all those who were unemployed with those who were not in the labour force but wanted a job and did not look for one; as well as those who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19 as a proportion of the potential labour force.

Potential labour force (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) includes people in the labour force (all employed and unemployed people), and people not in the labour force who wanted a job but didn't search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Information on population groups

Since July 2020, the LFS has included a question asking respondents to report the population group(s) to which they belong. Possible responses, which are the same as in the 2021 Census, include:

• White

• South Asian e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan

• Chinese

• Black

• Filipino

• Arab

• Latin American

• Southeast Asian e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai

• West Asian e.g., Iranian, Afghan

• Korean

• Japanese

• Other

According to the Employment Equity Act, visible minorities are "persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour." In the text, people who identify as a member of a population group (visible minority) are analyzed separately.

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

The seasonally adjusted data for retail trade and wholesale trade industries presented here are not published in other public LFS tables. A seasonally adjusted series is published for the combined industry classification (wholesale and retail trade).

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on October 8, 2021. September data will reflect labour market conditions during the week of September 12 to 18.

Products

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available online in the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The product "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app" (14200001) is also available. This interactive visualization application provides seasonally adjusted estimates by province, sex, age group and industry.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province and census metropolitan area, seasonally adjusted" (71-607-X) is also available. This interactive dashboard provides customizable access to key labour market indicators.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province, territory and economic region, unadjusted for seasonality" (71-607-X) is also available. This dynamic web application provides access to labour market indicators for Canada, province, territory and economic region.

The product Labour Force Survey: Public Use Microdata File (71M0001X) is also available. This public use microdata file contains non-aggregated data for a wide variety of variables collected from the Labour Force Survey. The data have been modified to ensure that no individual or business is directly or indirectly identified. This product is for users who prefer to do their own analysis by focusing on specific subgroups in the population or by cross-classifying variables that are not in our catalogued products.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: